Viète's formula

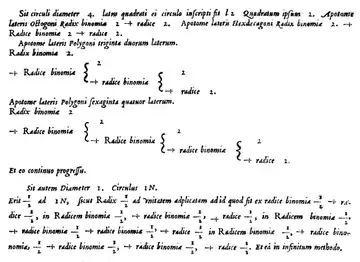

In mathematics, Viète's formula is the following infinite product of nested radicals representing the mathematical constant π:

It is named after François Viète (1540–1603), who published it in 1593 in his work Variorum de rebus mathematicis responsorum, liber VIII.[1]

Significance

At the time Viète published his formula, methods for approximating to (in principle) arbitrary accuracy had long been known. Viète's own method can be interpreted as a variation of an idea of Archimedes of approximating the circumference of a circle by the perimeter of a many-sided polygon,[1] used by Archimedes to find the approximation

However, by publishing his method as a mathematical formula, Viète formulated the first instance of an infinite product known in mathematics,[2][3] and the first example of an explicit formula for the exact value of .[4][5] As the first formula representing a number as the result of an infinite process rather than of a finite calculation, Viète's formula has been noted as the beginning of mathematical analysis[6] and even more broadly as "the dawn of modern mathematics".[7]

Using his formula, Viète calculated to an accuracy of nine decimal digits.[8] However, this was not the most accurate approximation to known at the time, as the Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī had calculated to an accuracy of nine sexagesimal digits and 16 decimal digits in 1424.[7] Not long after Viète published his formula, Ludolph van Ceulen used a closely related method to calculate 35 digits of , which were published only after van Ceulen's death in 1610.[7]

Interpretation and convergence

Viète's formula may be rewritten and understood as a limit expression

where , with initial condition .[9] Viète did his work long before the concepts of limits and rigorous proofs of convergence were developed in mathematics; the first proof that this limit exists was not given until the work of Ferdinand Rudio in 1891.[1][10]

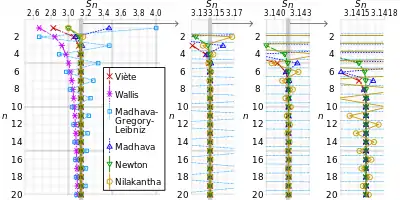

The rate of convergence of a limit governs the number of terms of the expression needed to achieve a given number of digits of accuracy. In the case of Viète's formula, there is a linear relation between the number of terms and the number of digits: the product of the first terms in the limit gives an expression for that is accurate to approximately digits.[8][11] This convergence rate compares very favorably with the Wallis product, a later infinite product formula for . Although Viète himself used his formula to calculate only with nine-digit accuracy, an accelerated version of his formula has been used to calculate to hundreds of thousands of digits.[8]

Related formulas

Viète's formula may be obtained as a special case of a formula given more than a century later by Leonhard Euler, who discovered that:

Substituting in this formula yields:

Then, expressing each term of the product on the right as a function of earlier terms using the half-angle formula:

gives Viète's formula.[1]

It is also possible to derive from Viète's formula a related formula for that still involves nested square roots of two, but uses only one multiplication:[12]

which can be rewritten compactly as

Many formulae similar to Viète's involving either nested radicals or infinite products of trigonometric functions are now known for and other constants such as the golden ratio.[3][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

Derivation

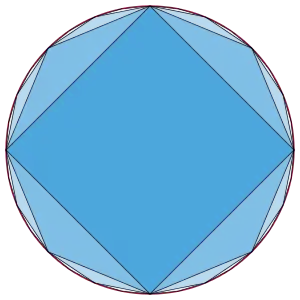

Viète obtained his formula by comparing the areas of regular polygons with and sides inscribed in a circle.[1][6] The first term in the product, √2/2, is the ratio of areas of a square and an octagon, the second term is the ratio of areas of an octagon and a hexadecagon, etc. Thus, the product telescopes to give the ratio of areas of a square (the initial polygon in the sequence) to a circle (the limiting case of a -gon). Alternatively, the terms in the product may be instead interpreted as ratios of perimeters of the same sequence of polygons, starting with the ratio of perimeters of a digon (the diameter of the circle, counted twice) and a square, the ratio of perimeters of a square and an octagon, etc.[19]

Another derivation is possible based on trigonometric identities and Euler's formula. By repeatedly applying the double-angle formula

one may prove by mathematical induction that, for all positive integers ,

The term goes to in the limit as goes to infinity, from which Euler's formula follows. Viète's formula may be obtained from this formula by the substitution .[4]

References

- Beckmann, Petr (1971). A history of (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: The Golem Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-88029-418-8. MR 0449960.

- De Smith, Michael J. (2006). Maths for the Mystified: An Exploration of the History of Mathematics and Its Relationship to Modern-day Science and Computing. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 165. ISBN 9781905237814.

- Moreno, Samuel G.; García-Caballero, Esther M. (2013). "On Viète-like formulas". Journal of Approximation Theory. 174: 90–112. doi:10.1016/j.jat.2013.06.006. MR 3090772.

- Morrison, Kent E. (1995). "Cosine products, Fourier transforms, and random sums". The American Mathematical Monthly. 102 (8): 716–724. arXiv:math/0411380. doi:10.2307/2974641. JSTOR 2974641. MR 1357488.

- Oldham, Keith B.; Myland, Jan C.; Spanier, Jerome (2010). An Atlas of Functions: with Equator, the Atlas Function Calculator. Springer. p. 15. ISBN 9780387488073.

- Maor, Eli (2011). Trigonometric Delights. Princeton University Press. pp. 50, 140. ISBN 9781400842827.

- Borwein, Jonathan M. (2013). "The Life of Pi: From Archimedes to ENIAC and Beyond". From Alexandria, Through Baghdad: Surveys and Studies in the Ancient Greek and Medieval Islamic Mathematical Sciences in Honor of J.L. Berggren (PDF). Springer. ISBN 9783642367359.

- Kreminski, Rick (2008). " to Thousands of Digits from Vieta's Formula". Mathematics Magazine. 81 (3): 201–207. doi:10.1080/0025570X.2008.11953549. JSTOR 27643107.

- Eymard, Pierre; Lafon, Jean Pierre (2004). "2.1 Viète's infinite product". The Number . American Mathematical Society. pp. 44–46. ISBN 9780821832462.

- Rudio, F. (1891). "Über die Konvergenz einer von Vieta herrührenden eigentümlichen Produktentwicklung". Z. Math. Phys. 36: 139–140.

- Osler, Thomas J. (2007). "A simple geometric method of estimating the error in using Vieta's product for ". International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 38 (1): 136–142. doi:10.1080/00207390601002799.

- Servi, L. D. (2003). "Nested square roots of 2". The American Mathematical Monthly. 110 (4): 326–330. doi:10.2307/3647881. JSTOR 3647881. MR 1984573.

- Nyblom, M. A. (2012). "Some closed-form evaluations of infinite products involving nested radicals". The Rocky Mountain Journal of Mathematics. 42 (2): 751–758. doi:10.1216/RMJ-2012-42-2-751. MR 2915517.

- Levin, Aaron (2006). "A geometric interpretation of an infinite product for the lemniscate constant". American Mathematical Monthly. 113 (6): 510–520. doi:10.2307/27641976. JSTOR 27641976. MR 2231136.

- Levin, Aaron (2005). "A new class of infinite products generalizing Viète's product formula for ". Ramanujan Journal. 10 (3): 305–324. doi:10.1007/s11139-005-4852-z. MR 2193382.

- Osler, Thomas J. (2007). "Vieta-like products of nested radicals with Fibonacci and Lucas numbers". The Fibonacci Quarterly. 45 (3): 202–204. MR 2437033.

- Stolarsky, Kenneth B. (1980). "Mapping properties, growth, and uniqueness of Vieta (infinite cosine) products". Pacific Journal of Mathematics. 89 (1): 209–227. doi:10.2140/pjm.1980.89.209. MR 0596932. Archived from the original on 2013-10-11. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

- Allen, Edward J. (1985). "Continued radicals". Mathematical Gazette. 69 (450): 261–263. doi:10.2307/3617569. JSTOR 3617569.

- Rummler, Hansklaus (1993). "Squaring the circle with holes". The American Mathematical Monthly. 100 (9): 858–860. doi:10.2307/2324662. JSTOR 2324662. MR 1247533.

External links

- Viète's Variorum de rebus mathematicis responsorum, liber VIII (1593) on Google Books. The formula is on the second half of p. 30.