Vincristine

Vincristine, also known as leurocristine and marketed under the brand name Oncovin among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat a number of types of cancer.[5] This includes acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, Hodgkin's disease, neuroblastoma, and small cell lung cancer among others.[5] It is given intravenously.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈvɪnˈkrɪstiːn/ ( |

| Trade names | Oncovin, Vincasar, Marqibo, others[2] |

| Other names | leurocristine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682822 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | n/a (not reliably absorbed by the GI tract)[3] |

| Protein binding | ~44%[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver, mostly via CYP3A4 and CYP3A5[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 19 to 155 hours (mean: 85 hours)[3] |

| Excretion | Faeces (70–80%), urine (10–20%)[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.289 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

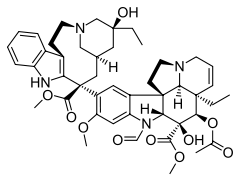

| Formula | C46H56N4O10 |

| Molar mass | 824.958 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Most people experience some side effects from vincristine treatment.[5] Commonly it causes a change in sensation, hair loss, constipation, difficulty walking, and headaches.[5] Serious side effects may include neuropathic pain, lung damage, or low white blood cells which increases the risk of infection.[5] Use during pregnancy may result in birth defects.[5] It works by stopping cells from dividing properly.[5]

Vincristine was first isolated in 1961.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] It is a vinca alkaloid that can be obtained from the Madagascar periwinkle Catharanthus roseus.[6]

Medical uses

Vincristine is delivered via intravenous infusion for use in various types of chemotherapy regimens.[3] Its main uses are in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma as part of the chemotherapy regimen CHOP, Hodgkin's lymphoma as part of MOPP, COPP, BEACOPP, or the less popular Stanford V chemotherapy regimen in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and in treatment for nephroblastoma.[3] It is also used to induce remission in ALL with dexamethasone and L-Asparaginase, and in combination with prednisone to treat childhood leukemia.[3] Vincristine is occasionally used as an immunosuppressant, for example, in treating thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) or chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP).[3]

Side effects

The main side effects of vincristine are chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, hyponatremia, constipation, and hair loss.

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy can be severe, and may be a reason to reduce or avoid using vincristine. The symptoms of this are progressive and enduring tingling numbness, pain and hypersensitivity to cold, beginning in the hands and feet and sometimes affecting the arms and legs.[8] One of the first symptoms of peripheral neuropathy is foot drop: A person with a family history of foot drop and/or Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) should avoid the taking of vincristine.[9]

Accidental injection of vinca alkaloids into the spinal canal (intrathecal administration) is highly dangerous, with a mortality rate approaching 100 percent. The medical literature documents cases of ascending paralysis due to massive encephalopathy and spinal nerve demyelination, accompanied by intractable pain, almost uniformly leading to death. Several patients have survived after aggressive and immediate intervention. Rescue treatments consist of washout of the cerebrospinal fluid and administration of protective medications.[10] Children may do better following this injury. One child, who was aggressively treated at the time of the injection, recovered almost completely with only mild neurological deficits.[11] A significant series of inadvertent intrathecal vincristine administration occurred in China in 2007 when batches of cytarabine and methotrexate (both often used intrathecally) manufactured by the company Shanghai Hualian were found to be contaminated with vincristine.[12]

The overuse of vincristine may also lead to drug resistance by overexpression of the p-glycoprotein pump (Pgp). There is an attempt to overcome resistance by the addition of derivatives and substituents to the vincristine molecule.[13]

Mechanism of action

Vincristine works partly by binding to the tubulin protein, stopping the tubulin dimers from polymerizing to form microtubules, causing the cell to be unable to separate its chromosomes during the metaphase.[14] The cell then undergoes apoptosis.[15] The vincristine molecule inhibits leukocyte production and maturation.[16] A downside, however, to Vincristine is that it does not only affect the division of cancer cells. It affects all rapidly dividing cell types, making it necessary for the very specific administration of the drug.[17]

Pharmacology

The natural extraction of vincristine from Catharanthus roseus is produced at a percent yield of less than 0.0003%. For this reason, alternate methods to produce synthetic vincristine are being used.[18] Vincristine is created through the semi-synthesis coupling of indole alkaloids vindoline and catharanthine in the vinca plant.[19] It can also now be synthesized through a stereocontrolled total synthesis technique which retains the correct stereochemistry at C18' and C2'. The absolute stereochemistry at these carbons is responsible for vincristine's anticancer activity.[18]

The liposome encapsulation of vincristine enhances the efficacy of the vincristine drug while simultaneously decreasing the neurotoxicity associated with it. Liposome encapsulation increases vincristine's plasma concentration and circulation lifetime in the body, and allows the drug to enter cells more easily.[20]

History

Having been used as a folk remedy for centuries, studies in the 1950s revealed that the rosy periwinkle Catharanthus roseus contained over 120 alkaloids, many of which are biologically active, the two most significant being vincristine and vinblastine.[21] While initial studies for its use in diabetes mellitus were disappointing, the discovery that it caused myelosuppression (decreased activity of the bone marrow) led to its study in mice with leukemia, whose lifespan was prolonged by the use of a vinca preparation. Treatment of the ground plant with Skelly-B defatting agent and an acid benzene extract led to a fraction termed "fraction A". This fraction was further treated with aluminium oxide, chromatography, trichloromethane, benz-dichloromethane, and separation by pH to yield vincristine.[22]

Vincristine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 1963 under the trade name Oncovin and was marketed by Eli Lilly Company.[14] The drug was initially discovered by a team at Lilly Research Laboratories where it was demonstrated that vincristine cured artificially induced leukemia in mice.[23] Vincristine also induced remission of acute leukemias of childhood.[24]

Production of vincristine required one ton of dried periwinkle leaves to produce one ounce of vincristine. Periwinkle was grown on a ranch in Texas.[25]

Society and culture

Suppliers

Until recently, two generic drug makers were suppliers of vincristine in the United States: Teva and Pfizer. In 2019 Teva stopped producing vincristine, leaving Pfizer as the only company in production. Teva has said that they will restart production, and expect it to be available in 2020.[26]

Shortage

In October 2019 an impending shortage was reported; no adequate substitute is known for treating childhood-cancers.[27]

Controversy

Pharmaceutical bioprospecting

Vincristine's origins are debated as an example of pharmaceutical bioprospecting in the fields of ethnobotany and ethnomedicine. Some consider the catharanthus roseus plant from which vincristine is derived, and its folk remedies to be endemic to Madagascar, and that Madagascar was denied royalties from vincristine sales.[28] However, catharanthus roseus has a documented history in folk medicine treatments in other locations. In 1963, Lilly researchers acknowledged that the plant was used in Brazil to treat hemorrhage, scurvy, toothaches, and chronic wounds; in the British West Indies to treat diabetic ulcers; and in the Philippines and South Africa as a oral hypoglycemic agent – but not as a treatment for cancer.[29]

Catharanthus roseus has been a cosmopolitan species since before the Industrial Revolution and the plant's use in folk remedies suggested general bioactivity for diabetes treatment, not cancer. In the mid-eighteenth century, botanist Judith Sumner recorded the arrival of catharanthus roses at London's Chelsea Physic Garden from the Jardin des plantes in Paris. It's unclear how the plant first arrived in Paris and the details of its origins in Madagascar beyond reports of its transport from Madagascar by early European explorers. Vincristine was initially distributed at cost to increase accessibility, though later switched to a for-profit model to recover the costs of production and development. According to Michael Brown, vincristine may not be a tidy example of pharmaceutical bioprospecting, but it demonstrates how pharmaceuticals with a history of use in folk medicine have intellectual property claims which are difficult to untangle.[30]

Since ethonobotanical studies and pharmaceutical bioprospecting depend on traditional knowledge from indigenous communities, the process of sourcing botanical and biological knowledge raises issues of the proper representation of the indigenous and local knowledge.[31]

Research

In 2012, the FDA approved a liposomal formulation of vincristine branded as Marqibo.[32][33][34]

A nano-particle bound version of vincristine was under development as of 2014.[35]

References

- "Vincristine". Dictionary.com. Random House, Inc. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- "NCI Drug Dictionary". NCI. 2011-02-02. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- Brayfield, A, ed. (13 December 2013). "Vincristine". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- "Oncovin, Vincasar PFS (vincristine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- "Vincristine Sulfate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-01-02. Retrieved Jan 2, 2015.

- Ravina E (2011). The evolution of drug discovery : from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1. Aufl. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 157–159. ISBN 9783527326693. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Chemotherapy-induced Peripheral Neuropathy. NCI Cancer Bulletin. Feb 23, 2010 [archived 2011-12-11];7(4):6.

- Graf WD, Chance PF, Lensch MW, Eng LJ, Lipe HP, Bird TD (April 1996). "Severe vincristine neuropathy in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A". Cancer. 77 (7): 1356–62. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1356::AID-CNCR20>3.0.CO;2-#. PMID 8608515.

- Qweider M, Gilsbach JM, Rohde V (March 2007). "Inadvertent intrathecal vincristine administration: a neurosurgical emergency. Case report". Journal of Neurosurgery. Spine. 6 (3): 280–3. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.3.280. PMID 17355029.

- Zaragoza MR, Ritchey ML, Walter A (January 1995). "Neurourologic consequences of accidental intrathecal vincristine: a case report". Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 24 (1): 61–2. doi:10.1002/mpo.2950240114. PMID 7968797.

- Hooker J, Bogdanich W (January 31, 2008). "Tainted Drugs Tied to Maker of Abortion Pill". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017.

- Sears JE, Boger DL (March 2015). "Total synthesis of vinblastine, related natural products, and key analogues and development of inspired methodology suitable for the systematic study of their structure-function properties". Accounts of Chemical Research. 48 (3): 653–62. doi:10.1021/ar500400w. PMC 4363169. PMID 25586069.

- Anticancer Drugs Targeting Tubulin and Microtubules. Elsevier. 2015-01-01. ISBN 9780444626493.

- Jordan MA (January 2002). "Mechanism of action of antitumor drugs that interact with microtubules and tubulin". Current Medicinal Chemistry. Anti-Cancer Agents. 2 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2174/1568011023354290. PMID 12678749.

- Silverman JA, Deitcher SR (March 2013). "Marqibo (vincristine sulfate liposome injection) improves the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of vincristine". Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 71 (3): 555–64. doi:10.1007/s00280-012-2042-4. PMC 3579462. PMID 23212117.

- Morris PG, Fornier MN (November 2008). "Microtubule active agents: beyond the taxane frontier". Clinical Cancer Research. 14 (22): 7167–72. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-08-0169. PMID 19010832.

- Kuboyama T, Yokoshima S, Tokuyama H, Fukuyama T (August 2004). "Stereocontrolled total synthesis of (+)-vincristine". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (33): 11966–70. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401323101. PMC 514417. PMID 15141084.

- "Pharmacognosy of Vinca Alkaloids". January 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-01-06.

- Waterhouse DN, Madden TD, Cullis PR, Bally MB, Mayer LD, Webb MS (2005). "Preparation, characterization, and biological analysis of liposomal formulations of vincristine". Methods in Enzymology. 391: 40–57. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(05)91002-1. ISBN 9780121827960. PMID 15721373.

- "Africa's gift to the world". Education in Chemistry. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- Johnson IS, Armstrong JG, Gorman M, Burnett JP (September 1963). "The Vinca Alkaloids: A New Class of Oncolytic Agents" (PDF). Cancer Research. 23 (8 Part 1): 1390–427. PMID 14070392.

- Johnson IS, Armstrong JG, Gorman M, Burnett JP (September 1963). "The Vinca Alkaloids: A New Class of Oncolytic Agents" (PDF). Cancer Research. 23 (8 Part 1): 1390–427. PMID 14070392.

- Johnson IS, Armstrong JG, Gorman M, Burnett JP (September 1963). "The Vinca Alkaloids: A New Class of Oncolytic Agents" (PDF). Cancer Research. 23 (8 Part 1): 1421. PMID 14070392.

- "Eli Lilly engineers developed a life-saving drug from the leaves of the periwinkle plant. – Treating Diabetes". Treating Diabetes. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Teva Pharmaceuticals (2019-11-13). "pic.twitter.com/gTY8Jga1kv". @TevaUSA. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- Rabin RC (14 October 2019). "Faced With a Drug Shortfall, Doctors Scramble to Treat Children With Cancer". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Plotkin M (1993). Tales of a Shaman's Apprentice: An Ethnobotanist Searches for New Medicines in the Amazon Rain Forest. New York: Penguin Books. p. 15-16.

- Johnson IS, Armstrong JG, Gorman M, Burnett JP (September 1963). "The Vinca Alkaloids: A New Class of Oncolytic Agents" (PDF). Cancer Research. 23 (8 Part 1): 1391. PMID 14070392.

- Brown, Michael (2003). Who Owns Native Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 136-38.

- Albuquerque UP, Nascimento AL, Soldati GT, Feitosa IS, Campos JL, Hurrell JA, et al. (February 19, 2019). "Ten important questions/issues for ethnobotanical research". Acta Botanica Brasilia. 33 (2): 2. doi:10.1590/0102-33062018abb0331. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- FDA press release Aug 9, 2012 Archived 2014-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Marqibo- vincristine sulfate kit". DailyMed. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "Drug Approval Package: Marqibo (vincristine sulfate) NDA #202497". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 September 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Bind Therapeutics conference call of Nov 6, 2014 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- "Vincristine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Vincristine and vinblastine

- Description and Natural History of the Periwinkle

- The Boger Route to (−)-Vindoline