Violence in art

The depiction of violence in high culture art has been the subject of considerable controversy and debate for centuries. In Western art, graphic depictions of the Passion of Christ have long been portrayed, as have a wide range of depictions of warfare by later painters and graphic artists. Theater and, in modern times, cinema have often featured battles and violent crimes, while images and descriptions of violence have always been a part of literature. Margaret Bruder states that the aestheticization of violence in film is the depiction of violence in a "stylistically excessive", "significant and sustained way" in which audience members are able to connect references from the "play of images and signs" to artworks, genre conventions, cultural symbols, or concepts.[1]

History in art

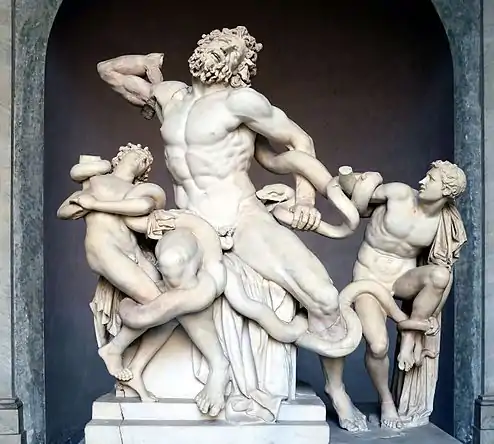

Antiquity

Plato proposed to ban poets from his ideal republic because he feared that their aesthetic ability to construct attractive narratives about immoral behaviour would corrupt young minds. Plato's writings refer to poetry as a kind of rhetoric, whose "...influence is pervasive and often harmful". Plato believed that poetry that was "unregulated by philosophy is a danger to soul and community". He warned that tragic poetry can produce "a disordered psychic regime or constitution" by inducing "a dream-like, uncritical state in which we lose ourselves in ...sorrow, grief, anger, [and] resentment". As such, Plato was in effect arguing that "What goes on in the theater, in your home, in your fantasy life, are connected" to what one does in real life.[2]

15th century – 17th century

_Photo_Paolo_Villa_FOTO9260.JPG.webp)

Politics of House of Medici and Florence dominate art depicted in Piazza della Signoria, making references to first three Florentine dukes. Besides aesthetical depiction of violence these sculptures are noted for weaving through a political narrative.[3]

The artist Hieronymus Bosch, from the 15th and 16th centuries, used images of demons, half-human animals and machines to evoke fear and confusion to portray the evil of man. The 16th-century artist Pieter Brueghel the Elder depicted "...the nightmarish imagery that reflect, if in an extreme fashion, popular dread of the Apocalypse and Hell".[4]

18th century – present

In the mid-18th century, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, an Italian etcher, archaeologist and architect active from 1740, did imaginary etchings of prisons that depicted people "stretched on racks or trapped like rats in maze-like dungeons", an "aestheticization of violence and suffering".[5]

In 1849, as revolutions raged in European streets and authorities were putting down protests and consolidating state powers, composer Richard Wagner wrote: "I have an enormous desire to practice a little artistic terrorism."[6]

Laurent Tailhade is reputed to have stated, after Auguste Vaillant bombed the Chamber of Deputies in 1893: "Qu'importent les victimes, si le geste est beau? [What do the victims matter, so long as the gesture is beautiful]." In 1929 André Breton's Second Manifesto on surrealist art stated that "L’acte surréaliste le plus simple consiste, revolvers aux poings, à descendre dans la rue et à tirer au hasard, tant qu’on peut, dans la foule" [The simplest Surrealist act consists of running down into the street, pistols in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd]."[6]

Power of representation

In high culture

High culture forms such as fine art and literature have aestheticized violence into a form of autonomous art. In 1991, University of Georgia literature professor Joel Black stated that "(if) any human act evokes the aesthetic experience of the sublime, certainly it is the act of murder". Black notes that "...if murder can be experienced aesthetically, the murderer can in turn be regarded as a kind of artist—a performance artist or anti-artist whose specialty is not creation but destruction" [7]

This conception of an aesthetic element of murder has a long history; in the 19th century, Thomas de Quincey wrote that

"Everything in this world has two handles. Murder, for instance, may be laid hold of by its moral handle... and that, I confess, is its weak side; or it may also be treated aesthetically, as the Germans call it—that is, in relation to good taste."[8]

In films

Film critics analyzing violent film images that seek to aesthetically please the viewer mainly fall into two categories. Critics who see depictions of violence in film as superficial and exploitative argue that it leads audience members to become desensitized to brutality, thus increasing their aggression. On the other hand, critics who view violence as a type of content, or as a theme, claim it is cathartic and provides "acceptable outlets for anti-social impulses".[1]

Adrian Martin argues that critics who hold violent cinema in high regard have developed a response to anti-violence advocates, "those who decry everything from Taxi Driver to Terminator 2 as dehumanising, desensitising cultural influences". Martin claims that critics who value aestheticized violence defend shocking depictions onscreen on the grounds that "screen violence is not real violence, and should never be confused with it". He claims that their rebuttal also claims that "movie violence is fun, spectacle, make-believe; it's dramatic metaphor, or a necessary catharsis akin to that provided by Jacobean theatre; it's generic, pure sensation, pure fantasy. It has its own changing history, its codes, its precise aesthetic uses."[9]

A Clockwork Orange is a 1971 film written, directed, and produced by Stanley Kubrick and based on the novel of the same name by Anthony Burgess. Set in a futuristic England (circa 1995, as imagined in 1965), it follows the life of a teenage gang leader named Alex. In Alexander Cohen's analysis of Kubrick's film, he argues that the "ultra-violence" of the young protagonist, Alex, "...represents the breakdown of culture itself". In the film, gang members are "...[s]eeking idle de-contextualized violence as entertainment" as an escape from the emptiness of their dystopian society. When the protagonist murders a woman in her home, Cohen states that Kubrick presents a "[s]cene of aestheticized death" by setting the murder in a room filled with "...modern art which depict scenes of sexual intensity and bondage"; as such, the scene depicts a "...struggle between high-culture which has aestheticized violence and sex into a form of autonomous art, and the very image of post-modern mastery".[10]

In Xavier Morales' review of Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill: Volume 1, entitled "Beauty and violence", he calls the film "a groundbreaking aestheticization of violence". Morales says that the film, which he calls "easily one of the most violent movies ever made", "a breathtaking landscape in which art and violence coalesce into one unforgettable aesthetic experience".[11] Morales argues that "... Tarantino manages to do precisely what Alex de Large was trying to do in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange: he presents violence as a form of expressive art...[in which the]...violence is so physically graceful, visually dazzling and meticulously executed that our instinctual, emotional responses undermine any rational objections we may have.[11]

Margaret Bruder, a film studies professor at Indiana University and the author of Aestheticizing Violence, or How To Do Things with Style, proposes that there is a distinction between aestheticized violence and the use of gore and blood in mass market action or war films. She argues that "aestheticized violence is not merely the excessive use of violence in a film". Movies such as the popular action film Die Hard 2 are very violent, but they do "not fall into the category of aestheticized violence because it is not stylistically excessive in a significant and sustained way".[1] For viewers of films with aestheticized violence, such as John Woo's movies, she claims that "One of the many pleasures" from watching Woo's films, such as Hard Target, is that it gets viewers to recognize how Woo plays with conventions "from other Woo films" and how it "connects up with films...which include imitations of or homages to Woo". Bruder argues that films with aestheticized violence such as "Hard Target, True Romance and Tombstone are [filled] with... signs" and indicators, so that "the stylized violence they contain ultimately serves as...another interruption in the narrative drive" of the film.[1]

Writing in The New York Times, Dwight Garner reviews the controversy and moral panic surrounding the 1991 novel and 2000 film American Psycho, which concerns Patrick Bateman, "an Exeter and Harvard grad, a gourmand, a tanning enthusiast and a ruthless fashion critic" who is also a serial killer. Garner concludes that the film was a "coal-black satire" in which "dire comedy mixes with Grand Guignol. There's demented opera in some of its scenes." The book, meanwhile, has acquired "grudging respect" and is "seen as a transgressive bag of broken glass that can be talked about alongside plasma-soaked trips like Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange".[12] Garner claims that the novel's author, Bret Easton Ellis, "was racing ahead of the culture" and that his book "was ahead of its time": "The culture has shifted to make room for Bateman. We've developed a taste for barbaric libertines with twinkling eyes and some zing in their tortured souls. Tony Soprano, Walter White from "Breaking Bad", Hannibal Lecter (who predates "American Psycho")—here are the most significant pop culture characters of the past 30 years... Thanks to these characters, and to first-person shooter video games, we’ve learned to identify with the bearer of violence and not just cower before him or her."

Theories and semiotic analysis

Fictional film or video

The culture industry's mass-produced texts and images about crime, violence, and war have been consolidated into genres. Film makers typically choose from a predictable range of narrative conventions and use stereotyped characters, and clichéd symbols and metaphors. Over time, certain styles and conventions of filming and editing are standardised within a medium or a genre. Some conventions tend to naturalise the content and make it seem more real. Other methods deliberately breach convention to create an effect, such as the canted angles, rapid edits, and slow motion shots used in films with aestheticized violence.

See also

Further reading

- Berkowitz, L. (ed) (1977; 1986): Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vols 10 & 19. New York: Academic Press

- Bersani, Leo and Ulysse Dutoit, The Forms of Violence: Narrative in Assyrian Art and Modern Culture (NY: Schocken Books, 1985)

- Black, Joel (1991) The Aesthetics of Murder. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Feshbach, S. (1955): The Drive-Reducing Function of Fantasy Behaviour, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 50: 3-11

- Feshbach, S & Singer, R. D. (1971): Television and Aggression: An Experimental Field Study. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kelly, George. (1955) The Psychology of Personal Constructs. Vol. I, II. Norton, New York. (2nd printing: 1991, Routledge, London, New York)

- Peirce, Charles Sanders (1931–58): Collected Writings. (Edited by Charles Hartshorne, Paul Weiss, & Arthur W Burks). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

References

- Bruder, Margaret Ervin (1998). "Aestheticizing Violence, or How To Do Things with Style". Film Studies, Indiana University, Bloomington IN. Archived from the original on 2004-09-08. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Griswold, Charles (2003-12-22). "Plato on Rhetoric and Poetry". In Edward N. Zalta (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2004 ed.). Stanford, CA: The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Mandel, C. "Perseus and the Medici." Storia Dell'Arte no. 87 (1996): 168

- Alsford, Stephen (2004-02-29). "Death - Introductory essay". Florilegium Urbanum. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- "db artmag". Deutsche Bank Art. 2005. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Dworkin, Craig (2006-01-17). "Trotsky's Hammer" (PDF). Salt Lake City, UT: Department of English, University of Utah. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-26. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Black, Joel (1991). The Aesthetics of Murder: A Study in Romantic Literature and Contemporary Culture. ISBN 0801841801. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- de Quincey, Thomas (1827). On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts (Zipped PDF download). ISBN 1-84749-133-2. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Martin, Adrian (2000). "The Offended Critic: Film Reviewing and Social Commentary". Senses of Cinema (8). ISSN 1443-4059. Archived from the original (Archive) on 2007-05-19. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Cohen, Alexander J. (1998). "Clockwork Orange and the Aestheticization of Violence". UC Berkeley Program in Film Studies. Archived from the original on 2007-05-15. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Morales, Xavier (2003-10-16). "Beauty and violence". The Record. Harvard Law School RECORD Corporation. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- Garner, Dwight (2016-03-24). "In Hindsight, an 'American Psycho' Looks a Lot Like Us". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-03-25.