W

W, or w, is the 23rd and fourth-to-last letter of the modern English and ISO basic Latin alphabets. It usually represents a consonant, but in some languages it represents a vowel. Its name in English is double-u,[note 1] plural double-ues.[1][2]

| W | |

|---|---|

| W w | |

| (See below) | |

| |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Latin script |

| Type | Alphabetic and Logographic |

| Phonetic usage | [w] [v] [β] [u] [uː] [ʊ] [ɔ] [ʋ] [ʕʷ] [ʙ] [◌ʷ] /ˈdʌbəl.juː/ [ɣ] |

| Unicode codepoint | U+0057, U+0077 |

| Alphabetical position | 23 |

| History | |

| Development | |

| Time period | ~600 to present |

| Descendants | • ʍ • ɯ ɰ • ₩ |

| Sisters | F U Ѵ У Ў Ұ Ү ו و ܘ וּ וֹ ࠅ 𐎆 𐡅 ወ વ ૂ ુ उ |

| Variations | (See below) |

| Other | |

| Other letters commonly used with | w(x) |

|

History

The classical Latin alphabet, from which the modern European alphabets derived, did not have the "W' character. The "W" sounds were represented by the Latin letter "U" (at the time, not yet distinct from "V").

The sounds /w/ (spelled ⟨V⟩) and /b/ (spelled ⟨B⟩) of Classical Latin developed into a bilabial fricative /β/ between vowels in Early Medieval Latin. Therefore, ⟨V⟩ no longer adequately represented the labial-velar approximant sound /w/ of Germanic phonology.

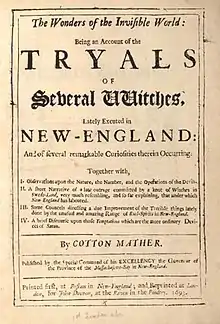

The Germanic /w/ phoneme was therefore written as ⟨VV⟩ or ⟨uu⟩ (⟨u⟩ and ⟨v⟩ becoming distinct only by the Early Modern period) by the earliest writers of Old English and Old High German, in the 7th or 8th centuries.[3] Gothic (not Latin-based), by contrast, had simply used a letter based on the Greek Υ for the same sound in the 4th century. The digraph ⟨VV⟩/⟨uu⟩ was also used in Medieval Latin to represent Germanic names, including Gothic ones like Wamba.

It is from this ⟨uu⟩ digraph that the modern name "double U" derives. The digraph was commonly used in the spelling of Old High German, but only in the earliest texts in Old English, where the /w/ sound soon came to be represented by borrowing the rune ⟨ᚹ⟩, adapted as the Latin letter wynn: ⟨ƿ⟩. In early Middle English, following the 11th-century Norman Conquest, ⟨uu⟩ gained popularity again and by 1300 it had taken wynn's place in common use.

Scribal realisation of the digraph could look like a pair of Vs whose branches crossed in the middle. Another, common in roundhand, kurrent and blackletter, takes the form of an ⟨n⟩ whose rightmost branch curved around as in a cursive ⟨v⟩.[4][5] It was used up to the nineteenth century in Britain and continues to be familiar in Germany.[note 2]

The shift from the digraph ⟨VV⟩ to the distinct ligature ⟨W⟩ is thus gradual, and is only apparent in abecedaria, explicit listings of all individual letters. It was probably considered a separate letter by the 14th century in both Middle English and Middle German orthography, although it remained an outsider, not really considered part of the Latin alphabet proper, as expressed by Valentin Ickelshamer in the 16th century, who complained that:

Poor w is so infamous and unknown that many barely know either its name or its shape, not those who aspire to being Latinists, as they have no need of it, nor do the Germans, not even the schoolmasters, know what to do with it or how to call it; some call it we, [... others] call it uu, [...] the Swabians call it auwawau[6]

In Middle High German (and possibly already in late Old High German), the West Germanic phoneme /w/ became realized as [v]; this is why, today, the German ⟨w⟩ represents that sound.

Pronunciation and use

| Language | Dialect(s) | Pronunciation (IPA) | Environment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cornish | /ʊ/ | Usually | Archaic spelling | |

| /w/ | Before vowels | |||

| Dutch | Flemish, Surinamese | /β/ | ||

| Standard | After u | |||

| /ʋ/ | Usually | |||

| English | /w/ | |||

| German | Standard | /v/ | ||

| Kashubian | /v/ | |||

| Kokborok | /ɔ/ | |||

| Kurdish | /w/ | |||

| Low German | /ʋ/ | |||

| Lower Sorbian | /v/ | |||

| North Frisian | /v/ | |||

| Polish | /v/ | |||

| Saterlandic | /v/ | |||

| Upper Sorbian | /β/ | |||

| Welsh | /ʊ/ | Usually | ||

| /w/ | Before vowels | |||

| West Frisian | /v/ | Before vowels | ||

| /w/ | After vowels | |||

| Wymysorys | /v/ | |||

English

English uses ⟨w⟩ to represent /w/. There are also a number of words beginning with a written ⟨w⟩ that is silent in most dialects before a (pronounced) ⟨r⟩, remaining from usage in Old English in which the ⟨w⟩ was pronounced: wreak, wrap, wreck, wrench, wroth, wrinkle, etc. Certain dialects of Scottish English still distinguish this digraph. In the Welsh loanword cwm it retains the Welsh pronunciation, /ʊ/. The letter is also used in digraphs: ⟨aw⟩ /ɔː/, ⟨ew⟩ /(j)uː/, ⟨ow⟩ /aʊ, oʊ/. W is the fifteenth most frequently used letter in the English language, with a frequency of about 2.56% in words.

Other languages

In Europe languages with ⟨w⟩ in native words are in a central-western European zone between Cornwall and Poland: English, German, Low German, Dutch, Frisian, Welsh, Cornish, Breton, Walloon, Polish, Kashubian, Sorbian, Wymysorys, Resian and Scandinavian dialects. German, Polish, Wymysorys and Kashubian use it for the voiced labiodental fricative /v/ (with Polish, related Kashubian and Wymysorys using Ł for /w/), and Dutch uses it for /ʋ/. Unlike its use in other languages, the letter is used in Welsh and Cornish to represent the vowel /u/ as well as the related approximant consonant /w/.

The following languages historically used ⟨w⟩ for /v/ in native words, but later replaced it by ⟨v⟩: Swedish, Finnish, Czech, Slovak, Latvian, Lithuanian, Estonian, Belarusian Łacinka. In Swedish and Finnish, traces of this old usage may still be found in proper names. In Hungarian remains in some aristocratic surnames, e.g. Wesselényi.

Modern German dialects generally have only [v] or [ʋ] for West Germanic /w/, but [w] or [β̞] is still heard allophonically for ⟨w⟩, especially in the clusters ⟨schw⟩, ⟨zw⟩, and ⟨qu⟩. Some Bavarian dialects preserve a "light" initial [w], such as in wuoz (Standard German weiß [vaɪs] '[I] know'). The Classical Latin [β] is heard in the Southern German greeting Servus ('hello' or 'goodbye').

In Dutch, ⟨w⟩ became a labiodental approximant /ʋ/ (with the exception of words with -⟨eeuw⟩, which have /eːβ/, or other diphthongs containing -⟨uw⟩). In many Dutch-speaking areas, such as Flanders and Suriname, the /β/ pronunciation is used at all times.

In Finnish, ⟨w⟩ is seen as a variant of ⟨v⟩ and not a separate letter. It is, however, recognized and maintained in the spelling of some old names, reflecting an earlier German spelling standard, and in some modern loan words. In all cases, it is pronounced /ʋ/.

In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, ⟨w⟩ is named double-v and not double-u. In these languages, the letter only exists in old names, loanwords and foreign words. (Foreign words are distinguished from loanwords by having a significantly lower level of integration in the language.) It is usually pronounced /v/, but in some words of English origin it may be pronounced /w/.[7][8] The letter was officially introduced in the Danish and Swedish alphabets as late as 1980 and 2006, respectively, despite having been in use for much longer. It had been recognized since the conception of modern Norwegian, with the earliest official orthography rules of 1907.[9] ⟨W⟩ was earlier seen as a variant of ⟨v⟩, and ⟨w⟩ as a letter (double-v) is still commonly replaced by ⟨v⟩ in speech (e.g. WC being pronounced as VC, www as VVV, WHO as VHO, etc.) The two letters were sorted as equals before ⟨w⟩ was officially recognized, and that practice is still recommended when sorting names in Sweden.[10] In modern slang, some native speakers may pronounce ⟨w⟩ more closely to the origin of the loanword than the official /v/ pronunciation.

Multiple dialects of Swedish and Danish use the sound however. In Denmark notably in Jutland, where the northern half use it extensively in traditional dialect, and multiple places in Sweden. It is used in southern Swedish, for example in Halland where the words "wesp" (wisp) and "wann" (water) are traditionally used.[11] In northern and western Sweden there are also dialects with /w/. Elfdalian is a good example, which is one of many dialects where the Old Norse difference between v (/w/) and f (/v/ or /f/) is preserved. Thus "warg" from Old Norse "vargr", but "åvå" from Old Norse "hafa".

In the alphabets of most modern Romance languages (excepting far northern French and Walloon), ⟨w⟩ is used mostly in foreign names and words recently borrowed (le week-end, il watt, el kiwi). The digraph ⟨ou⟩ is used for /w/ in native French words; ⟨oi⟩ is /wa/ or /wɑ/. In Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese, [w] is a non-syllabic variant of /u/, spelled ⟨u⟩.

The Japanese language uses "W", pronounced /daburu/, as an ideogram meaning "double".[12] It is also a short form of an Internet slang term for "www", used to denote laughter, which is derived from the word warau (笑う, meaning "to laugh"). Variations of this slang include kusa (草, meaning "grass"), which have originated from how repeated instances of "www" look like blades of grass.

In Italian, while the letter ⟨w⟩ is not considered part of the standard Italian alphabet, the character is often used in place of Viva (hooray for...), generally in the form in which the branches of the Vs cross in the middle, at least in handwriting (in fact it could be considered a monogram).[13] The same symbol written upside down indicates abbasso (down with...).

in the Kokborok language, ⟨w⟩ represents the open-mid back rounded vowel /ɔ/.

In Vietnamese, ⟨w⟩ is called vê đúp, from the French double vé. It is not included in the standard Vietnamese alphabet, but it is often used as a substitute for qu- in literary dialect and very informal writing.[14][15] It's also commonly used for abbreviating Ư in formal documents, for example Trung Ương is abbreviated as TW[16] even in official documents and document ID number[17]

"W" is the 24th letter in the Modern Filipino Alphabet and has its English name. However, in the old Filipino alphabet, Abakada, it was the 19th letter and had the name "wah".[18]

In Washo, lower-case ⟨w⟩ represents a typical /w/ sound, while upper-case ⟨W⟩ represents a voiceless w sound, like the difference between English weather and whether for those who maintain the distinction.

Under the 2020 version of amendment of Kazakh alphabets by president Tokayev, the W has selected as replacement of Cyrillic У, and represents one of Kazakh pronunciation: [w], Kazakh pronunciation: [ʊw] and/or Kazakh pronunciation: [ʏw].

Other systems

In the International Phonetic Alphabet, ⟨w⟩ is used for the voiced labial-velar approximant.

Other uses

W is the symbol for the chemical element tungsten, after its German (and alternative English) name, Wolfram.[20] It is also the SI symbol for the watt, the standard unit of power. It is also often used as a variable in mathematics, especially to represent a complex number or a vector.

Name

Double-u, whose name reflects stages in the letter's evolution when it was considered two of the same letter, a double U, is the only modern English letter whose name has more than one syllable.[note 3] It is also the only English letter whose name is not pronounced with any of the sounds that the letter typically makes in words, with the exception of H for some speakers.

Some speakers shorten the name "double u" into "dub-u" or just "dub"; for example, University of Wisconsin, University of Washington, University of Wyoming, University of Waterloo, University of the Western Cape and University of Western Australia are all known colloquially as "U Dub", and the automobile company Volkswagen, abbreviated "VW", is sometimes pronounced "V-Dub".[21] The fact that many website URLs require a "www." prefix has been influential in promoting these shortened pronunciations, as many speakers find the phrase "double-u double-u double-u" inconveniently long.

In other Germanic languages, including German (but not Dutch, in which it is pronounced wé), its name is similar to that of English V. In many languages, its name literally means "double v": Portuguese duplo vê,[note 4] Spanish doble ve (though it can be spelled uve doble),[22][note 5] French double vé, Icelandic tvöfalt vaff, Czech dvojité vé, Estonian kaksisvee, Finnish kaksois-vee, etc.

Former U.S. president George W. Bush was given the nickname "Dubya" after the colloquial pronunciation of his middle initial in Texas, where he spent much of his childhood.

Related characters

Ancestors, descendants and siblings

- 𐤅: Semitic letter Waw, from which the following symbols originally derive

- U : Latin letter U

- V : Latin letter V

- Ⱳ ⱳ : W with hook

- Ꝡ ꝡ : Latin letter VY

- Ꟃ ꟃ : Anglicana W, used in medieval English and Cornish[23]

- IPA-specific symbols related to W: ʍ ɯ ɰ ʷ

- Uralic Phonetic Alphabet-specific symbols related to W:[24] U+1D21 ᴡ LATIN LETTER SMALL CAPITAL W and U+1D42 ᵂ MODIFIER LETTER CAPITAL W

- ʷ : Modifier letter small w is used in Indo-European studies[25]

- ꭩ : Modifier letter small turned w is used in linguistic transcriptions of Scots[26]

- W with diacritics: Ẃ ẃ Ẁ ẁ Ŵ ŵ Ẅ ẅ Ẇ ẇ Ẉ ẉ ẘ

- װ (double vav): the Yiddish and Hebrew equivalent of W

Ligatures and abbreviations

- ₩ : Won sign, capital letter W with double stroke

Computing codes

| Preview | W | w | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER W | LATIN SMALL LETTER W | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 87 | U+0057 | 119 | U+0077 |

| UTF-8 | 87 | 57 | 119 | 77 |

| Numeric character reference | W | W | w | w |

| EBCDIC family | 230 | E6 | 166 | A6 |

| ASCII 1 | 87 | 57 | 119 | 77 |

- 1 Also for encodings based on ASCII, including the DOS, Windows, ISO-8859 and Macintosh families of encodings.

Other representations

See also

- Digamma (Ϝ), the archaic Greek letter for /w/

- Voiced labio-velar approximant

- Wh (digraph)

- W stands for Work in physics

- W is the symbol for "watt" in the International System of Units (SI)

References

Informational notes

- Pronounced /ˈdʌbəl.juː/ in formal situations, but colloquially often /ˈdʌbəjuː/, /ˈdʌbjuː/, /ˈdʌbəjə/ or /ˈdʌbjə/, with a silent l.

- Writing manuals that include it include Edward Cocker's The Pen's Triumph of 1658 and engravings of the roundhand calligraphy of Charles Snell and sometimes George Bickham. See also Florian Hardwig's gallery of images of its use in the German-speaking countries.

- However, "Izzard" was formerly a two-syllable pronunciation of the letter Z.

- In Brazilian Portuguese, it is dáblio, which is a loanword from the English double-u.

- In Latin American Spanish, it is doble ve, similar regional variations exist in other Spanish-speaking countries.

Citations

- "W", Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989); 'W", Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition (1989); Merriam-Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged (1993) Merriam Webster

- Brown & Kiddle (1870) The institutes of grammar, p. 19.

Double-ues is the plural of the name of the letter; the plural of the letter itself is written W's, Ws, w's, or ws. - "Why is 'w' pronounced 'double u' rather than 'double v'? : Oxford Dictionaries Online". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- Shaw, Paul. "Flawed Typefaces". Print magazine. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- Berry, John. "A History: English round hand and 'The Universal Penman'". Typekit. Adobe Systems. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Arm w ist so unmer und unbekannt, dasz man schier weder seinen namen noch sein gestalt waiszt, die Lateiner wöllen sein nit, wie sy dann auch sein nit bedürffen, so wissen die Teütschen sonderlich die schülmaister noch nitt was sy mit im machen oder wie sy in nennen sollen, an ettlichen enden nennet man in we, die aber ein wenig latein haben gesehen, die nennen in mit zwaien unterschidlichen lauten u auff ainander, also uu ... die Schwaben nennen in auwawau, wiewol ich disen kauderwelschen namen also versteh, das es drey u sein, auff grob schwäbisch au genennet." cited after Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch.

- "W, w - Gyldendal - Den Store Danske". Denstoredanske.dk. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 24, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), page 1098

- Aars, Jonathan; Hofgaard, Simon Wright (1907). Norske retskrivnings-regler med alfabetiske ordlister (in Norwegian). W. C. Fabritius & Sønner. pp. 19, 84. NBN 2006081600014. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- "Veckans språkråd 2006" (in Swedish). July 5, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- Peter, von Möller (1858). Ordbok öfver Halländska landskapsmålet. Lund: Berlingska boktryckeriet. p. 17.

- "Let the pretending to be injured begin". No-sword.jp. June 10, 2006. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- Zingarelli, Nicola (1945). Vocabolario della lingua italiana (7 ed.). Bologna: Nicola Zanichelli. p. 1713.

- Nhật My (May 19, 2009). "Ngôn ngữ thời @ của teen". VnExpress (in Vietnamese). FPT Group. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- Trần Tư Bình (November 30, 2013). "Viết tắt chữ Việt trong ngôn ngữ @". Chim Việt Cành Nam (in Vietnamese) (53).

- "Từ viết tắt: Trung ương". wcag.dongnai.gov.vn. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- VIỆT NAM, ĐẢNG CỘNG SẢN. "Hệ thống văn bản". dangcongsan.vn (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- "W, w, pronounced: wah". English, Leo James Tagalog-English Dictionary. 1990., page 1556.

- Caslon, William IV (1816). Untitled fragment of a specimen book of printing types, c. 1816. London: William Caslon IV. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- Bureau, Commodity Research (September 14, 2006). The CRB Commodity Yearbook 2006 with CD-ROM. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470083949. Retrieved November 7, 2017 – via Google Books.

- Volkswagen. "VW Unpimp – Drop it like its hot". Youtube.com. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- "Real Academia Española elimina la Ch y ll del alfabeto". Taringa!. November 5, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2011.

- Everson, Michael (July 26, 2017). "L2/17-238: Proposal to add LATIN LETTER ANGLICANA W to the UCS" (PDF).

- Everson, Michael; et al. (March 20, 2002). "L2/02-141: Uralic Phonetic Alphabet characters for the UCS" (PDF). Unicode.org.

- Anderson, Deborah; Everson, Michael (June 7, 2004). "L2/04-191: Proposal to encode six Indo-Europeanist phonetic characters in the UCS" (PDF). Unicode.org.

- Everson, Michael (May 5, 2019). "L2/19-075R: Proposal to add six phonetic characters for Scots to the UCS" (PDF).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to W. |

| Look up W or w in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |