Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (Wabenaki, Wobanaki, translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner") are a First Nations and Native American confederation of four principal Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot. The Western Abenaki are also considered members, being a loose identity for a number of allied tribal peoples like the Pennacook, Sokoki, Cowasuck, Missiquoi, and Arsigantegok, among others.

Wabanaki Confederacy Wabana'ki Mawuhkacik | |

|---|---|

| 1680s–1862 | |

Wampum belt

Coat of arms

| |

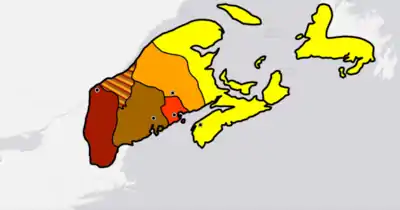

Yellow - Miꞌkmaꞌki, Orange - Wolastokuk, Red - Peskotomuhkatik, Brown - Pαnawαhpskewahki, Cayenne - Ndakinna

The dots are the listed capitals, being political centers in Wabanaki. The mixed region is territory outside of the historic ranges of the five tribes. It was acquired from the Haudenosaunee between 1541-1608 with Abenaki peoples having moved in by the time Samuel de Champlain came to the region establishing Quebec City. | |

| Capital | Panawamskek, Odanak, Sipayik, Meductic, and Eelsetkook |

| Recognised regional languages | Abenaki Malecite-Passamaquoddy Mi'kmawi'simk English French |

| Religion | Traditional belief systems, including Midewiwin and Glooscap narratives; Christianity |

| Government | Confederation |

| History | |

• Established | 1680s |

• Disestablished | 1862 |

• Re-established | 1993 |

| Area | |

| 1680s | 349,405 km2 (134,906 sq mi) |

| Today part of | |

The Passamaquoddy wampum records describe that there were once fourteen tribes along with many bands that were once part of the Confederation.[1]:117 Native tribes like that of the Norridgewock, Etchemin, and Canibas, through massacres, tribal consolidation, and ethnic label shifting were absorbed into the five larger national identities.

Members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, the Wabanakik, are in and named for the area which they call Wabanaki ("Dawnland"), roughly the area that became the French colony of Acadia. It is made up of most of present-day Maine in the United States, and New Brunswick, mainland Nova Scotia, Cape Breton Island, Prince Edward Island and some of Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River, Anticosti, and Newfoundland in Canada. The Western Abenaki live on lands in Quebec as well as New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts of the United States.[2]

History

Before formation (1520s-1680s)

.jpg.webp)

Small-scale confederacies in and around what would become the Wabanaki Confederacy were common at the time of post-Viking European contact. The earliest known confederacy was the Mawooshen Confederacy located within the historic Eastern Penobscot cultural region. Its capital, Kadesquit, located around modern Bangor, Maine, would play a significant role as a political hub for the future Wabanaki Confederacy.[4]

When Samuel de Champlain made contact with the Mawooshen in Pemetic (present-day Mount Desert Island, Maine) in 1604, he noted that the people actually had quite a few European goods. Post-Viking Europeans had been traveling around the region as late as the 1520s. Champlain had a positive encounter on Pemetic, and would make his way up north to the Passamaquoddy and establish a settlement at St. Croix Maine, and created the French colonial region Acadia on top of preexisting tribal territory. The communities of Acadia and Wabanaki coexisted in the same territory with independent yet allied governments. Champlain continued to establish cities throughout Wabanaki territory, including Saint John (1604) and Quebec City (1608), among others. This started trade and military relations between the French and the local Algonquin tribes including the Mawooshen and later Wabanaki that would last until the end of the French and Indian/Seven Years' War.[5]

The English made contact with the Mawooshen in 1605. English Captain George Weymouth met with them in a large village on the Kennebec River, only to kidnap five people to bring back to England for interrogation for places to settle by Sir Ferdinando Gorges. Of the kidnapped people, Chief Tahánedo was the only one known to be returned home. He was brought back with the settlers of the short-lived Popham Colony (1607-1608) in hopes of establishing good relations. Local tribes remained uncomfortable with the English colony.[6]:83–84 [7]

Journalist Avery Yale Kamila in 2020 did claim the account of the Weymouth voyage has culinary significance because it "is the first time a European recorded the Native American use of nut milks and nut butters."[8][9] A Wabanaki infant formula recipe made from nuts and corn was reported in 1725 by Elizabeth Hanson.

Champlain would go on to forge strong French relations with Algonquin tribes up until his death in 1635. Somewhere in the area near Ticonderoga and Crown Point, New York (historians are not sure which of these two places, but Fort Ticonderoga historians claim that it occurred near its site), Champlain and his party encountered a group of Iroquois. In a battle that began the next day, 250 Iroquois advanced on Champlain's position, and one of his guides pointed out the three chiefs. In his account of the battle, Champlain recounts firing his arquebus and killing two of them with a single shot, after which one of his men killed the third. The Iroquois turned and fled. This action set the tone for poor French-Iroquois relations for the rest of the century.

The Battle of Sorel occurred on June 19, 1610, with Samuel de Champlain supported by the Kingdom of France and his allies, the Wendat people, Algonquin people and Innu people against the Mohawk people in New France at present-day Sorel-Tracy, Quebec. Champlain's forces armed with the arquebus engaged and slaughtered or captured nearly all of the Mohawks. The battle ended major hostilities with the Mohawks for twenty years.

In and around this time, more French arrived as traders in what is now Nova Scotia, forming settlements such as Port-Royal. With many of the French settlements in Eastern lands, the French would more often trade weapons and other goods to the local Mi'kmaq. The influx of European goods changed the social and economic landscape as tribes became more dependent on European goods than each other, harming the kinship ties and reciprocal exchange that originally supported the local economy. Subsistence hunting shifted into a competition for animals like beaver and for access to European traders, which caused population movements and intraband—as well as interband—disputes.[1]:124 Allied with the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy, the Mi'kmaq fought with their Western Mawooshen (Western Abenaki/Penobscot) neighbors for goods as trading relations broke down, and this power imbalance would lead to a war. In 1615 the Mi'kmaq and their allies killed the Mawooshen Grand Chief Bashabas in his village. War would become more costly as the Mi'kmaq, their allies, and the Mawooshen faced a widespread pandemic known as "The Great Dying" (1616-1619), killing around 70-95% of the local population.[10][4]

By the 1640s, conflicts with each other started to make Iroquois advances harder to combat for what would become the Wabanaki peoples, but also the Algonquians (tribe east of Quebec City), the Innu, and French to manage separately. Aided by French Jesuits, this led to the formation of a large Algonquian league against the Iroquois, who were making significant territorial land gains around the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River region. By the 1660s, tribes of Western Abenaki peoples as far south as Massachusetts had joined the league. This defensive alliance would not only prove to be successful, but it helped repair the relationship among the Eastern Algonquians and promote greater cooperation and notably political teamwork over the coming decades.[1]:124

Abenaki people soon came into contact with English settlers moving into their lands in Massachusetts, as well as southern Maine and New Hampshire under the colonizing efforts of people directed by Ferdinando Gorges and John Mason respectively.[7] This helped establish stronger ties between the local Algonquin people and the French, who themselves were historic rivals with the English and challenged their claims, while at the same time pushing the English closer to the Iroquois, the historic rival of the Abenaki peoples.

This growing tension with two large and organized political adversaries, the Iroquois and especially the English, over the next 20 years would lead to an Algonquian uprising during King Philip's War (1675-1676), followed by the First Abenaki War (1675-1678), which would soon after bring the four/fourteen tribes together in an effort to strengthen both defensive and diplomatic power, formally establishing the Wabanaki Confederacy.[11]

The Wabanaki Confederacy (1680s)

The First Abenaki War saw native peoples throughout the Eastern Algonquian lands face a new common and powerful enemy together, the English. The war led to large-scale depopulation of English settlements north of the Saco River in the district of Maine, a political situation made more complicated when the Massachusetts Bay Colony was force to relinquish control of Maine to the heirs of Ferdinando Gorges in 1676.[12] This required them to find the heirs to buy back the land making up Maine, and then to issue grants for people to settle once again. This conflict as a whole was not without significant losses for the soon-to-be Wabanaki peoples, and it became clear that larger and more organized political cooperation would be necessary for the tribes to challenge the further encroachment onto their lands.

The First Abenaki War ended with the Treaty of Casco, which forced all the tribes to recognize English property rights in southern Maine and coastal New Hampshire. In return the English recognized "Wabanaki" sovereignty by committing themselves to pay Madockawando, as a "grandchief" of the Wabanaki alliance, a symbolic annual fee of "a peck of corn for every English Family." They also recognized the Saco River as the border.

The Caughnawaga Council was a large neutral political gathering in the Mohawk territory that occurred every three years for tribes and tribal confederacies within and around the Great Lakes, East Coast, and Saint Lawrence River. At one of these councils in the 1680s, the Eastern Algonquians came together to form their own confederation with the aid of an Ottawa "sakom" (leaders of the tribes). The Mawooshen Confederacy, of which Madockawando was part, was put in a situation where it would be absorbed into a larger confederacy that incorporated the tribes into each other's internal politics and would start to hold their own councils as a new political union.[1]:125–126 In this new union, the tribes would see each other as brothers, as family. The union helped challenge Iroquois hostilities along the Saint Lawrence River over land and resources which was becoming a bigger problem for almost all the Eastern Algonquians to manage separately, but also provided political organization and might to push back collectively against growing English colonial expansionism, as well as mitigated large losses in the recent three-year war with them.

The political union incorporated many political elements from other local confederacies like the Iroquois and Huron, the role of wampum council conduct being a major example. This political unit allowed for the safe passage of people through each of their territories (including camping and subsisting on the land), safer trade networks from the western agricultural centers to the eastern gathering economies (copper/pelts) through non-aggression pacts and sharing natural resources from their respected habitats, freedom to move to each and any of the other's villages along with organizing inter-tribal marriages, and a large-scale defensive alliance to fend off attacks in their now shared territory. Madockawando for instance would later move from Penobscot lands to Maliseet lands, living in their political hub of Meductic until his death.[1]

This useful confederation not only made organization among themselves easier, but also established a large political entity giving them more leverage to deal with allies like the French and later the United States when it came to working out treaties and trade.

All of this led to the formal creation of what is now called the "Wabanaki Confederacy." This political union was known by many names, but is remembered as "Wabanaki", which shares a common etymological origin with the name "Abenaki". The Mi'kmaq usually referred to it as Buduswagan (convention council), based on the word putus/budus (orator). Their Maliseet and Passamaquoddy neighbors also used this name. The Passamaquoddy also called it Tolakutinaya (be related to one another). The Penobscot named it Bezegowak (those united into one) or Gizangowak (completely united).[13]

The Passamaquoddy wampum record tells about the event that took place at the Caughnawaga Council that led to the formation of the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Silently they sat for seven days. Everyday, no one spoke. That was called, "The Wigwam is Silent." Every councilor had to think about what he was going to say when they made the laws. All of them thought about how the fighting could be stopped. Next they opened up the wigwam. It was now called "Every One of Them Talks." And during that time they began their council....When all had finished talking, they decided to make a great fence; and in addition they put in the centre a great wigwam within the fence; and also they made a whip and placed it with their father. Then whoever disobeyed him would be whipped. Whichever of his children was within the fence - all of them had to obey him. And he always had to kindle their great fire, so that it would not burn out. This is where the Wampum Laws originated. That fence was the confederacy agreement....There would be no arguing with one another again. They had to live like brothers and sisters who had the same parent....And their parent, he was the great chief at Caughnawaga. And the fence and the whip were the Wampum Laws. Whoever disobeyed them, the tribes together had to watch him.[1]:125–126

Wabanaki Confederacy government

The Wabanaki Confederacy were governed by a council of elected sakoms, tribal leaders who were frequently leaders of the watershed their village was on. Sakoms themselves were more of respected listeners and debaters than simply rulers. They often were older members of extended families who had shown a talent for settling disputes, collecting food for the needy, and maintaining the corporate resources of the band, both tangible and intangible.[1]:123–124

Wabanaki politics was fundamentally rooted on reaching a consensus on issues, often after much debate. Sakoms frequently used stylized metaphorical speech at council fires, trying to win over others sakoms. Sakoms who were skilled at debate often became quite influential in the Confederacy, often being older men who were called nebáulinowak or "riddle men."[14]:499

"They have reproached me a hundred times because we fear our Captains, while they laugh at and make sport of theirs. All the authority of their chief is in his tongue's end; for he is powerful in so far as he is eloquent; and even if he kills himself talking and haranguing he will not be obeyed unless he please the [Indians]."[15]:A-13

Wabanaki sakoms held regular conventions at their various "council fires" (seats of government) whenever there was a need to call each other together. In a council fire, they would sit in a large rectangle with all members facing each other. Each Sakom member would have a chance to speak and be listened to, with the understanding that they would do the same for the others. Each tribe a sakom was part of also had a "kinship" status, being that they are brothers some members were older and younger. Familiar ritual, reciprocity, and metaphorically ascribed kinship statuses enabled strangers to feel secure and comfortable with one another. They were encouraged to think of themselves as elder or younger brothers, and familiarity and mutual trust flourished in the confederacy because intertribal relationships were not exclusively diplomatic and political. The formal greetings were inevitably followed by house-to-house visiting, feasting and dancing, communal prayer, and athletic contests.[14][1]:122–127 The lack of a single centralized capital complemented the Wabanaki government style, as sakoms were able to shift their political influence to any part of the nation that needed it. This could mean bringing leadership near or away from conflict zones. When a formal internal agreement was reached, not one but often at least five representatives speaking on behalf of their respective tribe and nation as a whole would set off to negotiate.[15]:167–172

Probably influenced by diplomatic exchanges with Huron allies and Iroquois enemies (especially since the 1640s), the Wabanaki began using wampum belts in their diplomacy in the course of the 17th century, when envoys took such belts to send messages to allied tribes in the confederacy. A number of important symbols and ceremonies were used to keep the Confederacy alive. Wampum belts called gelusewa'ngan, meaning "speech", played an important role in maintaining Wabanaki political institutions.[14]:507 Each wampum belt or strand had a design on it, which stood for a message from one tribe to the Confederacy, or from the Confederacy to a member tribe. The belts were kept at political centers like Kahnawake, Tobique, and Digby as records of all past exchanges among the five tribes. There they were "read" aloud at meetings.[16][14] The design on each belt did not stand for precise words, but represented the main idea of the message and helped the delegate remember what to say as they delivered it. The threads at the top of each belt or string were left loose to symbolize "emanating words". (Threads at the ends of wampum used for decoration or jewelry were braided or tied together.) One of the last keepers of the "Wampum Record" and one of the last Wabanaki/Passamaquoddy delegates to go to Caughnawaga was Sepiel Selmo. Keepers of the wampum record were called putuwosuwin which involved a mix of oral history with understanding the context behind the placement of wampum on the belts.[1]:116

Wampum shells arranged on strings in such a manner, that certain combinations suggested certain sentences or certain ideas to the narrator, who, of course, knew his record by heart and was merely aided by the association of the shell combinations in his mind with incidents of the tale or record which he was rendering.[1]:116–117

What was not recorded through wampum was remembered in a long chain of oral record-keeping which village elders were in charge of, with multiple elders being able to double check each other. In the 1726 treaty following Dummer's War, the Wabanaki had to challenge a claim that land was sold to English settlers, of which not a single elder had a memory. After much challenge with New England Lt. Governor William Dummer, Wabanaki leadership was very careful and took their time to make sure there was as little misunderstanding of the terms of the land and peace as possible. The terms were worked out little by little each day, from August 1st through 5th. When an impasse was found, leadership would withdraw to talk about the matter thoroughly among themselves before reconvening to debate once more, with all representatives debating on the same page, with their most well thought-out arguments.[15]:167–172

The Wabanaki never had a formal "grandchief" or single leader of the whole confederacy, and thus never had a single seat of government. Though Madockawando was treated as such in the Treaty of Casco, and his descendants such as Wabanaki Lieutenant-Governor John Neptune would maintain an elevated status in the confederacy, both officially had the same amount of power as any other sakom.[6]:255–257 This would continue throughout the entire history of the Wabanaki, as the confederacy remained decentralized so as to never give more power to any of the member tribes. This meant that all major decisions had to be thoroughly debated by sakoms at council fires, which created a strong political culture empowering the best debaters.

The four/fourteen tribes were not completely independent from each other. Not only was it possible for sanctions to be placed on each other for creating problems, but also when a sakom died, newly elected sakoms would be confirmed by allied Wabanaki tribes who would visit following a year of mourning in the village.[14]:503 An event to appoint a new sakom, known as a Nská'wehadin or "assembly", could last several weeks. They tended to select chiefs who could maintain harmonious relationships with one another and whose authority at the local level was based on a mandate from the entire confederacy.[1]:128 Tribes had a lot of autonomy, but they built a culture which normalized being involved in each others' political affairs to help maintain unity and cooperation.[14]:498 This event would continue until 1861 when the last Nská'wehadin was held in Old Town, Maine, shortly before the end of the confederacy.[14]:504 Occasionally some sakoms were known to ignore the will of the confederacy, most often the case for tribes on the border of European powers who had the most to lose during peace after war. Gray Lock, who was among the most successful wartime Wabanaki sakoms, refused to make peace after the 1722-1726 Dummer's War, given that his Vermont lands were being settled by the English. He would hold a successful guerrilla war for the following two decades, never being caught, and successfully deterring settlers entering his lands.[17]

Kinship metaphors like "Brother", "Father", or "Uncle" in their original linguistic context were much more complex than when they were when translated into English or French. Such terms were used to understand the status and role of a diplomatic relationship. For instance, for the other tribes in the Wabanaki the Penobscot were called the ksés'i'zena or "our elder brother". The Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Mi'kmaq in this order of "age" were called ndo'kani'mi'zena or "our younger brother".[14] The Maliseet referred to the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy as ksés'i'zena and the Mi'kmaq as ndo'kani'mi'zena. Concepts like this were also found in other confederacies like the Iroquois. In the Wabanaki context, such terms indicated concepts like the Penobscot looking out for the well-being of the younger brothers, while younger brothers would support and respect the wisdom of an older brother. The idea of being related helped establish unity and cooperation in Wabanaki culture, using family as a metaphor to overcome factionalism and to quell internal conflicts like a family would. The age rank was based on the tribes proximity to the Caughnawaga Council, with the Penobscots being the closest. Before the massacre of the Norridgewock and the slow abandonment of their settlements and integration into their neighbor tribes, they were once seen as an older brother to the Penobscot.[18]

This system was not seen as something indicating superiority per se, but rather a way to perceive a relationship in a manner that reflected the cultural norms of the Wabanaki. When the Wabanaki called the French Canadian governor and King of France "our father", it was a relationship built upon a sense of respect and protective care that reflected a Wabanaki father-son relationship. This was not well understood by diplomats from France and England who did not live with the peoples, seeing such terms as acknowledgment of subservience. Miscommunication over these terms was one of the biggest challenges in Wabanaki and European diplomacy. The culture and government style of Wabanaki would strongly push for a clear and mutual understanding of political matters, both internally and externally.[19]

The Wabanaki saw and called the Ottawa "our father" for both their role as a leader in the Caughnawaga Council and in being a tribe that helped found Wabanaki and issued binding judgments that help maintain order.[1]:126 But this did not mean the Wabanaki ever saw themselves as subservient to the Ottawa in any way, this was the same with the French.

There were men's and women's roles. Wabanaki women seem to have played no overt part in decision making, but they had effective veto power. The departure of embassies was customarily delayed when the hosts "take out the wampum - the one for delaying the departure - and they read it. They would say to them, 'Our mother has hidden your paddle. She is granting you a very great favour.'" This means, they are not allowing them to leave. The women's acquiescence is, of course, critical here.[1]:126

Military

The confederacy has historically united five North American Algonquian language-speaking First Nations peoples. It played a key role in supporting the colonial rebels of the American Revolution via the Treaty of Watertown, signed in 1776 by the Miꞌkmaq and Passamaquoddy, two of its constituent nations. Under this treaty, Wabanaki soldiers from Canada are still permitted to join the US military. They have done so in 21st-century conflicts in which the US has engaged, including the Afghanistan War and the Iraq War.

Members of the Wabanaki Confederacy are:

- (Eastern) Abenaki or Panuwapskek (Penobscot)

- (Western) Abenaki

- Míkmaq (Miꞌkmaq, L'nu)

- Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy)

- Wolastoqew , Wolastoq (Maliseet or Malicite)

Nations in the Confederacy are also closely allied with the Innu of Nitassinan and the Algonquin and with the Iroquoian-speaking Wyandot. Wabanaki were also allies of the Huron in the past. Together they jointly invited the colonization of Quebec City and LaHave and the formation of New France in 1603, in order to put French guns, ships, and forts between themselves and the powerful Mohawk people to the west. Today the only remaining Huron First Nation resides mostly in the suburbs of Quebec City, in Nionwentsïo, a legacy of this protective alliance. In Acadia, the Wabanaki people and Acadians freely had relations and intermarriages until the Expulsion of the Acadians by the British.

The Wabanaki ancestral homeland stretches from Newfoundland, Canada to the Merrimack River valley in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, United States. This became a hotly contested borderland between the English of colonial New England and French Acadia following the European settlement in the early 17th century. Members of the Wabanaki Confederacy of Acadia participated in 7 major wars, beginning with King Phillip's War in 1675, before the British defeated the French in North America:

- King Phillip's War (1675–1678)

- King William's War (1688–1697)

- Queen Anne's War (1702–1713)

- Dummer's War (1722–1725)

- King George's War (1744–1748)

- Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755)

- French and Indian War (1754–1763)

During this period, their population was radically decimated due to many decades of warfare, but also because of famines and devastating epidemics of infectious disease.[6]

After 1783 and the end of the American Revolutionary War, Black Loyalists, freedmen from the British colonies, were resettled by the British in this historical territory. They had promised slaves freedom if they left their rebel masters and joined the British. Three thousand freedmen were evacuated to Nova Scotia by British ships from the colonies after the war.

Many intermarriages occurred between these peoples, especially in southwest Nova Scotia from Yarmouth to Halifax. Suppression of Acadian, Black and Mi'kmaq people under British rule tended to force these peoples together as allies of necessity. Some white and black parents abandoned their mixed-race children on reserves to be raised in Wabanaki culture, even as late as the 1970s.

The British declared the Wabanaki Confederacy forcibly disbanded in 1862. However the five Wabanaki nations still exist, continued to meet, and the Confederacy was formally re-established in 1993.

Contemporary

The Wabanaki Confederacy gathering was revived in 1993. The first reconstituted confederacy conference in contemporary time was developed and proposed by Claude Aubin and Beaver Paul and hosted by the Mi'kmaq community of Listuguj under the leadership of Chief Brenda Gideon Miller. The sacred Council Fire was lit again, and embers from the fire have been kept burning continually since then.[2] The revival of the Wabanaki Confederacy brought together the Passamaquoddy Nation, Penobscot Nation, Maliseet Nation, the Miꞌkmaq Nation, and the Abenaki Nation.

Following the 2010 UNDRIP declaration (Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples), the member nations began to re-assert their treaty rights, and the Wabanaki leadership emphasized the continuing role of the Confederacy in protecting natural capital.[20]

There were meetings amongst allies,[21] a "Water Convergence Ceremony" in May 2013,[22] with Algonquin grandmothers in August 2013 supported by Kairos Canada,[23][24] and with other indigenous groups.

Alma Brooks represented the Confederacy at the June 2014 UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.[25] She discussed the Wabanaki/Wolostoq position on the Energy East pipeline.[26] Opposition to its construction has been a catalyst for organizing:

"On May 30 [2015], residents of Saint John will join others in Atlantic Canada, including Indigenous people from the Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), Passamaquoddy and Mi'kmaq, to march to the end of the proposed pipeline and draw a line in the sand." This was widely publicized.[27]

2015 Grandmothers' Declaration

These and other preparatory meetings set an agenda for the August 19–22, 2015, meeting[28] which produced the promised Grandmothers' Declaration[29] "adopted unanimously at N'dakinna (Shelburne, Vermont) on August 21, 2015". The Declaration included mention of:

- Revitalization and maintenance of indigenous languages

- Article 25 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on land, food, and water

- A commitment to "establish decolonized maps"

- The Wingspread Statement on the Precautionary Principles

- Obligation of governments to "obtain free, prior, and informed consent" before "further infringement"

- A commitment to "strive to unite the Indigenous Peoples; from coast to coast", e.g. against Tar Sands.

- Protecting food, "seeds, waters, and lands, from chemical and genetic contamination"

- Recognizes and confirms the unique decision-making structures of the Wabanaki Peoples in accordance with Article 18 of the UN DRIP indigenous decision-making institutions:

- "Our vision is to construct a Lodge, which will serve as a living constitution and decision-making structure for the Wabanaki Confederacy."

- Recognizes the Western Abenaki living in Vermont and the United States as a "People" and member nation

- Peace and friendship with "the Seven Nations of Iroquois"

Position on ecological and health issues

On October 15, 2015, Alma Brooks spoke to the New Brunswick Hydrofracturing Commission, applying the Declaration to current provincial industrial practices:[30]

- She criticized the "industry of hydro-fracturing for natural gas in our territory" because "our people have not been adequately consulted ... have been abused and punished for taking a stand," and cited traditional knowledge of floods, quakes and salt lakes in New Brunswick;

- Criticized Irving Forestry Companies for having "clear cut our forests [and] spraying poisonous carcinogenic herbicides such as glyphosate all over 'our land', to kill hardwood trees, and other green vegetation," harming human and animal health;

- Noted "Streams, brooks, and creeks are drying up; causing the dwindling of Atlantic salmon and trout. Places where our people gather medicines, hunt deer, and moose are being contaminated with poison. We were not warned about the use of these dangerous herbicides, but since then cancer rates have been on the rise in Maliseet Communities; especially breast cancer in women and younger people are dying from cancer."

- Open pit mining "for tungsten and molybdenum [which] require tailing ponds; this one designated to be the largest in the world [which] definitely will seep out into the environment. A spill or leak from the Sisson Brook open-pit mine will permanently contaminate the Nashwaak River; which is a tributary of the Wolastok (St. John River) and surrounding waterways. This is the only place left clean enough for the survival of the Atlantic salmon."

- "Oil pipelines and "refineries ... bent on contaminating and destroying the very last inch of (Wəlastokok) Maliseet territory."

- Rivers, lakes, streams, and lands.. contaminated "to the point that we are unable to gather our annual supply of fiddleheads [an edible fern], and medicines."

- The "duty to consult with aboriginal people ... has become a meaningless process,"..."therefore governments and/or companies do not have our consent to proceed with hydro-fracturing, open-pit mining, or the building of pipelines for gas and oil bitumen."

2016

The Passamaquoddy will host the 2016 Wabanaki Confederacy Conference.

"Wabanaki Confederacy" in various indigenous languages

The term Wabanaki Confederacy in many Algonquian languages literally means "Dawn Land People".

| Language | "Easterner(s)" literally "Dawn Person(s)" |

"Dawn Land" (nominative) |

"Dawn Land" (locative) |

"Dawn Land Person" |

"Dawn Land People" or the "Wabanaki Confederacy" |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naskapi | Waapinuuhch | ||||

| Massachusett language | Wôpanâ(ak) | ||||

| Quiripi language | Wampano(ak) | Wampanoki | |||

| Miꞌkmaq | Wapnaꞌk(ik) | Wapnaꞌk | Wapnaꞌkik | Wapnaꞌki | Wapnaꞌkiyik |

| Maliseet-Passamaquoddy | Waponu(wok) | Waponahk | Waponahkik | Waponahkew | Waponahkiyik/Waponahkewiyik |

| Abenaki-Penobscot | Wôbanu(ok) | Wôbanak | Wôbanakik | Wôbanaki | Wôbanakiak |

| Algonquin | Wàbano(wak) | Wàbanaki | Wàbanakìng | Wàbanakì | Wàbanakìk |

| Ojibwe | Waabano(wag) | Waabanaki | Waabanakiing | Waabanakii | Waabanakiig/Waabanakiiyag |

| Odawa | Waabno(wag) | Waabnaki | Waabnakiing | Waabnakii | Waabnakiig/Waabnakiiyag |

| Potawatomi | Wabno(weg) | Wabneki | Wabnekig | Wabneki | Wabnekiyeg |

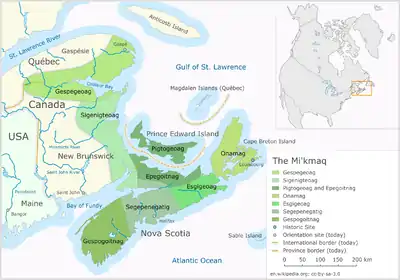

Maps

Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket)

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket) Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook

References

- Walker, Willard (December 1, 1998). "The Wabanaki Confederacy". Maine History Journal. Voume 37: 110–139.

- Toensing, Gale Courey. "Sacred fire lights the Wabanaki Confederacy", Indian Country Today (June 27, 2008), ICT Media Network

- "Then & Now". www.vamonde.com. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- "Davistown Museum". www.davistownmuseum.org. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- Petersen, James; Blustain, Malinda; Bradley, James (2004). ""Mawooshen" Revisited: Two Native American Contact Period Sites on the Central Maine Coast". Archaeology of Eastern North America. Eastern States Archeological Federation. 32: 1–71. JSTOR 40914474.

- Prins, Harald (December 2007). Asticou's Island Domain: Wabanaki Peoples at Mount Desert Island 1500-2000. National Park Service, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Gratwick, Harry (April 10, 2010). Hidden History of Maine. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61423-134-9.

- Kamila, Avery Yale (November 8, 2020). "Americans have been enjoying nut milk and nut butter for at least 4 centuries". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- "Wabanaki Enjoying Nut Milk and Butter for Centuries". Atowi. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- "Wabanaki Timeline - The Great Dying | Research | Abbe Museum". archive.abbemuseum.org. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- Prins, Harald. "Storm Clouds Over Wabanakiak". GenealogyFirst.ca. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- "The Revised Statutes of the State of Maine" (PDF). Maine State Legislature: xiii.

- Prins, Harald (2002). The Crooked Path of Dummer's Treaty: Anglo-Wabanaki Diplomacy and the Quest for Aboriginal Rights. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba: Winnipeg: University of Manitoba. p. 363.

- Speck, Frank (1915). "The Eastern Algonkian Wabanaki Confederacy". American Anthropologist. 17 (3): 492–508. doi:10.1525/aa.1915.17.3.02a00040.

- The Wabanakis of Maine and the Maritimes. Bath, Maine: American Friends Service Committee. 1989.

- "Oral History".

- "Biography – GRAY LOCK – Volume III (1741-1770) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- Bourque, Bruce (2004). Twelve Thousand Years: American Indians in Maine. University of Nebraska Press. p. 238.

- "The Wabanaki". www.wabanaki.com. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "Wabanaki tribes cheer UN declaration that defends their rights". Bangor Daily News — BDN Maine. Bangordailynews.com. December 19, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Ally". Maine-Wabanaki REACH. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Wabanaki Water Convergence ceremony – Kairos". Nationtalk.ca. May 31, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Kairos Times: October 2013". Kairoscanada.org. October 15, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Letter from Algonquin Grandmothers, attending Wabanaki Confederacy Conference". Nationtalk.ca. October 11, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- Warden, Rachel (June 6, 2014). "Indigenous women unite at UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues". Rabble.ca. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ""Energy East pipeline poses 'enormous threat' to environment:" Advocates for renewable energy hold parallel summit". NB Media Co-op. October 14, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "The stories of Energy East in New Brunswick | Ricochet". Ricochet.media. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "WABANAKI CONFEDERACY CONFERENCE" (PDF). Abenakitribe.org. August 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Wabanaki Confederacy Conference Statement 2015". Willinolanspeaks.com. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Alma Brooks: Statements to New Brunswick Hydrofracturing Commission Oct 2015". Willinolanspeaks.com. October 18, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

Further reading

- McBride, Bunny (2001). Women of the Dawn.

- Mead, Alice (1996). Giants of the Dawnland: Eight Ancient Wabanaki Legends.

- Prins, Harald E. L. (2002). "The Crooked Path of Dummer's Treaty: Anglo-Wabanaki Diplomacy and the Quest for Aboriginal Rights". Papers of the Thirty-Third Algonquian Conference. H.C. Wolfart, ed. Winnipeg: U Manitoba Press. pp. 360–378.

- Speck, Frank G. "The Eastern Algonkian Wabanaki Confederacy". American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 17, No. 3 (July–September 1915), pp. 492–508

- Walker, Willard. "The Wabanaki Confederacy". Maine History 37 (3) (1998): 100–139.

External links

- Indian Treaties

- Native Languages of the Americas: Wabanaki Confederacy

- "Wabanaki People—A Story of Cultural Continuity", timeline curriculum by Abbe Museum

- Dr. Harald E. L. Prins, "Storm Clouds over Wabanakiak Confederacy Diplomacy Until Dummer's Treaty (1727)", Wabanaki Confederacy website

- Miingignoti-Keteaoag , a partnership for the way of life of the Wabanaki Nations (mirror)