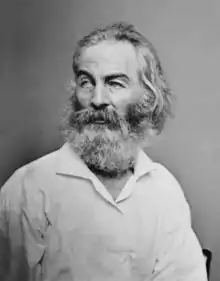

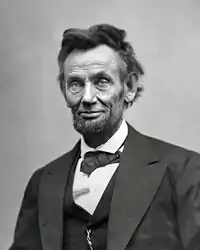

Walt Whitman and Abraham Lincoln

The American poet Walt Whitman greatly admired Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, and was deeply affected upon his assassination, writing several poems as elegies and giving a series of lectures on Lincoln.

Shortly after Lincoln was killed on April 16, 1865, Whitman hastily wrote the first of his Lincoln poems, "Hush'd Be the Camps To-Day". In the months that followed, he wrote two further poems: "O Captain! My Captain!" and "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd", both of which had appeared in Sequel to Drum-Taps by the end of the year. The poems were well received and popular upon publication—particularly "My Captain!"—and in the years that followed Whitman fashioned himself as an interpreter of Lincoln. In 1871 he published his fourth poem on Lincoln, "This Dust Was Once the Man", and all four poems were grouped together in the "President Lincoln's Burial Hymn" cluster of Passage to India. In 1881, the poems were grouped into the "Memories of President Lincoln" cluster of Leaves of Grass.

From 1879 to 1890 Whitman gave several lectures on Lincoln that centered around his assassination and helped to improve his reputation and the reputation of his poems. Critical reception of the cluster has varied since their publication. "My Captain!" was immensely popular, particularly before the mid-20th century and is still considered one of his most popular works, and "Lilacs" is often listed as one of Whitman's finest works.

Background

Walt Whitman established his reputation as a poet in the late 1850s to early 1860s with the 1855 release of Leaves of Grass. Whitman intended to write a distinctly American epic and developed a free verse style inspired by the cadences of the King James Bible.[1][2] The brief volume, first released in 1855, was considered controversial by some,[3] with critics particularly objecting to Whitman's blunt depictions of sexuality and the poem's "homoerotic overtones".[4] Whitman's work received significant attention following praise for Leaves of Grass by American transcendentalist lecturer and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson.[5][6]

At the start of the American Civil War, Whitman moved from New York to Washington, D.C., where he held a series of government jobs—first with the Army Paymaster's Office and later with the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[7][8] He volunteered in the army hospitals as a nurse.[9] Whitman's poetry was informed by his wartime experience, maturing into reflections on death and youth, the brutality of war, and patriotism.[10] Whitman's brother, Union Army soldier George Washington Whitman, was taken prisoner in Virginia in September 1864, and held for five months in Libby Prison, a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp near Richmond.[11] On February 24, 1865, George was granted a furlough to return home because of his poor health, and Whitman traveled to his mother's home in New York to visit his brother.[12] While visiting Brooklyn, Whitman contracted to have his collection of Civil War poems, Drum-Taps, published.[13] In June 1865, James Harlan, the Secretary of the Interior, found a copy of Leaves of Grass and, considering the collection vulgar, fired Whitman from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[14]

Whitman and Lincoln

C. K. Williams (2010)[15]

In 1856[16] Whitman wrote that "I would be much pleased to see some heroic, shrewd, fully-informed, healthy-bodied, middle-aged, beard-faced American blacksmith or boatman come down from the West across the Alleghanies [sic], and walk into the Presidency, dressed in a clean suit of working attire, and with the tan all over his face, breast, and arms; I would certainly vote for that sort of man, possessing the due requirements, before any other candidate."[17] This is considered to be an early description of a "Lincolnesque" figure. In 1858 Whitman first mentioned Lincoln by name in writing.[16] Whitman first saw Lincoln on February 19, 1861, as Lincoln was traveling through New York City.[18] Whitman noticed the President-elect's "striking appearance" and "unpretentious dignity", and trusted Lincoln's "supernatural tact" and "idiomatic Western genius".[19][20]

Although they never met, Whitman saw Abraham Lincoln several other times between 1861 and 1865, sometimes in close quarters.[19][20] In a letter, Whitman estimated that he saw Lincoln around twenty or thirty times. Lincoln passed Whitman several times and nodded to him, interactions that Whitman detailed in letters to his mother. Barton notes that they were not "evidence of recognition", and Lincoln likely nodded to many passersby as he traveled.[21] Whitman and Lincoln were in the same room two times; at the White House reception after Lincoln's first inauguration and when Whitman visited John Hay at the White House.[22]

In August 1863 Whitman wrote in The New York Times "I see the president almost every day".[23] He greatly admired the President,[23] writing in October 1863, "I love the President personally."[24] Whitman considered himself and Lincoln to be "afloat in the same stream" and "rooted in the same ground".[19][20] Whitman and Lincoln shared similar views on slavery and the Union— both men opposed allowing slavery to expand across the US, but considered preservation of the union more important.[25] Whitman was a consistent supporter of Lincoln's politics, and similarities have been noted in their literary styles and inspirations. Whitman later declared that "Lincoln gets almost nearer me than anybody else."[19][20][23]

It is unclear how much Lincoln knew about Whitman, though he certainly knew who Whitman was and that Whitman admired him.[23] There is an account of Lincoln reading Whitman's Leaves of Grass poetry collection in his office, and another of the president saying "Well, he looks like a man!" upon seeing Whitman in Washington, D.C., but these accounts may be fictitious.[19][20][26] Whitman was present at Lincoln's second inauguration in 1865 and left D.C. shortly after to visit his family.[27]

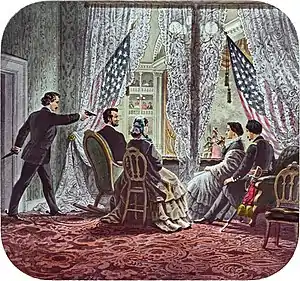

On April 15, 1865, Lincoln was assassinated, shortly after the end of the American Civil War.[28] His death greatly moved Whitman.[29]

Memories of President Lincoln

| Title | First published |

|---|---|

| "Hush'd Be the Camps To-Day" | Drum-Taps, May 1865 |

| "O Captain! My Captain!" | The Saturday Press, November 4, 1865 |

| "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd" | Sequel to Drum-Taps, December 1865 |

| "This Dust Was Once the Man" | Passage to India, 1871 |

The first poem that Whitman wrote on Lincoln's assassination was "Hush'd Be the Camps To-Day", which was dated April 19, 1865—the day of Lincoln's funeral in Washington.[lower-alpha 1][31] Although Drum-Taps had already begun the process of being published on April 1, Whitman felt it would be incomplete without a poem on Lincoln's death and hastily added "Hush'd Be the Camps To-Day".[32] He halted further distribution of the work[29] and stopped publication on May 1, mainly to develop his Lincoln poems.[33] He followed that poem with "O Captain! My Captain!" and "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd".[31] "My Captain" first appeared in The Saturday Press on November 4, 1865,[14][34] and was published with "Lilacs" in Sequel to Drum-Taps around the same time. Although Sequel to Drum-Taps had been published in early October,[35] the copies were not ready for distribution until December[36] and Whitman's choice to publish "My Captain" in The Saturday Press is sometimes considered a 'teaser' for Sequel.[35]

In 1866, Whitman's friend William D. O'Connor published The Good Gray Poet: A Vindication, a short work aimed at promoting Whitman and his reputation. The book presented Whitman as Lincoln's "foremost poetic interpreter" and proclaimed "Lilacs" "the grandest and the only grand funeral music poured around Lincoln's bier".[37]

Whitman's fourth and final poem on Lincoln was not written until 1871.[38][39][40] The four poems were first grouped together in the 1871 "President Lincoln's Burial Hymn" cluster of Passage to India. Ten years later, in the 1881 edition of Leaves of Grass, the grouping was named "Memories of President Lincoln".[41][42] "This Dust" is the only poem in the cluster that was not originally published in Drum-Taps or Sequel to Drum-Taps.[38][39][40] The poems were not substantially revised after being published.[43]

Whitman wrote two other poems on Lincoln's assassination that were not included in the cluster.[44] Shortly before Whitman's death he wrote a final poem titled "Abraham Lincoln, Born Feb. 12, 1809" in honor of Lincoln's birthday.[45] It appeared in the New York Herald on February 12, 1888.[46] The poem is just two lines long and little noted.[45]

Lectures

In 1875 Whitman published Memoranda During the War, a collection of diary entries, including a telling of Lincoln's death written from the point of view of someone present at the assassination. The New York Sun published that section in 1876; it was well received. Whitman, by then in failing health, attempted to present himself as neglected, unfairly criticized, and deserving of pity in the form of financial aid.[47] He was soon presented with the idea of giving a series of 'Lincoln Lectures' by Richard Watson Gilder and several friends; the goal was to raise Whitman's profile and money to benefit him. Whitman adapted his New York Sun article for the lectures.[48]

Whitman gave a series of lectures on Abraham Lincoln from 1879 to 1890. They centered around the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, but also covered years leading up to and during the American Civil War and sometimes included readings of poems such as "O Captain! My Captain!". The lectures began as a benefit for Whitman and were generally popular and well received.[49][50] Whitman's biographer Justin Kaplan wrote in 1980 that Whitman's 1887 lecture in New York City and its after-party marked the closest he came to "social eminence on a large scale."[51] In 1885 Whitman contributed an essay about his experiences with Lincoln to a volume being compiled by Allen Thorndike Rice.[52]

Reception

The cluster is considered to have improved Whitman's reputation.[53] Drum-Taps and its Sequel received mixed reviews by critics upon publication,[54] some poems were generally praised; particularly "My Captain" and, to a lesser extent, "Lilacs".[55] Henry James accused Whitman of exploiting the tragedy of Lincoln's death to serve himself.[54] Conversely, after reading Sequel to Drum-Taps the author William Dean Howells became convinced that Whitman had cleaned the "old channels of their filth" and poured "a stream of blameless purity" through; he would become a prominent defender of Whitman.[56][57] Whitman's Lincoln poetry was not immediately popular.[58] His lectures helped to raise the perception of the poems around the nation, and by the late 1870s the work was often listed with James Russell Lowell's "Commemoration Ode" as some of the best poetry honoring Lincoln.[59] The literary critic William Michael Rossetti considered "My Captain!" the noblest expression of the country's grief.[60] As Whitman's profile grew with his poetry, many people assumed that he had been close to the president while Lincoln was alive.[61]

After 1881 Whitman became increasingly known for "My Captain!" and the persona he cultivated through such measures as the lectures.[62] "My Captain!" became Whitman's most popular poem; it was the only one of his poems to be anthologized before his death.[63] His 1892 obituary in the New York Herald wrote that "To the mass of people Whitman's poetry will always remain as a sealed book, but there are few who are not able to appreciate the beauty of 'O Captain! My Captain!'"[64] In 1920 Léon Bazalgette, a French literary critic, wrote that "Lilacs" and "My Captain" established Whitman as the poet "who sings the American nation" and that his Lincoln poems represented "the heart of America in tears".[65] In 1943, Henry Seidel Canby wrote that Whitman's poems on Lincoln have become known as "the poems of Lincoln".[66] "My Captain" was called the most popular poem ever written on Lincoln by the scholar William Pannapacker.[67] The historian Roy Basler deemed "My Captain!" and "Lilacs" Whitman's two most famous poems.[68]

Opinions on "My Captain!" and "Commemoration Ode" remained high until reappraisal in the 20th century. As they became less highly thought of, "Lilacs" took their place.[59] In 1962 Whitman's biographer James E. Miller wrote that the poems in the cluster besides "Lilacs" were "competently executed expressions of public sentiment on a high public occasion" but lacked the personal emotion contained in "Lilacs", which also utilized symbolism to magnify "the meaning of the tragedy beyond the national level".[69] Charles M. Oliver wrote in 2006 that Whitman's works on Lincoln represent him at his most eloquent.[70] Whitman's Lincoln poems are considered to include one of his best ("Lilacs") and one of his most popular ("My Captain").[29][71][72]

Analysis

Whitman as interpreter of Lincoln

Justin Kaplan (1980)[73]

Shortly after Lincoln's death, hundreds of poems were written on the topic. The historian Stephen B. Oates noted that "never had the nation mourned so over a fallen leader".[67] Whitman was ready and willing to write poetry on the topic,[74] seizing the opportunity to present himself as an "interpreter of Lincoln" as a way to increase the readership of Leaves of Grass while honoring a man he had admired.[75] In 2004, Pannapacker described the cluster as a "mixture of innovation and opportunism".[68] The scholar Daniel Aaron concludes that "Death enshrined the Commoner [and . . .] Whitman placed himself and his work in the reflected limelight."[74] Pannapacker agrees, noting that instead of harming Whitman's image, they served to appropriate Lincoln's "consecrated" status for Whitman himself.[76]

The work of poets such as Whitman and Lowell helped to establish Lincoln as the 'first American', epitomizing the newly reunited America.[77] Whitman portrayed Lincoln as the captain of the ship of state and made his assassination into a monumental event. Aaron wrote that Whitman treated Lincoln's death as a moment that could unite the American people and enrich "the soil of art".[74] The historian Merrill D. Peterson wrote to a similar effect, noting that Whitman's poetry placed Lincoln's assassination firmly in the American consciousness.[78] Kaplan considers responding to Lincoln's death to have been Whitman's "crowning challenge".[79] He considers Whitman's writing in poems such as "My Captain" and "Lilacs" to mark a "retreat from the idiomatic boldness and emotional directness of Whitman's earlier work."[80]

Pannapacker concludes that "Whitman's celebration of Lincoln instead of himself" allowed him to reach the "heights of fame". Whitman presented himself as Lincoln's "avuncular eulogizer" and made Lincoln the "redeemer of the promise of American democracy".[76] The scholar Martha C. Nussbaum considers Lincoln to be the only individual subject of love in Whitman's poetry.[81] The Chilean critic Armando Donoso wrote that Lincoln's death allowed Whitman to find significance in "the feelings that the Civil War had aroused in him".[82] The critic M. Jimmie Killingsworth wrote that Lincoln's death allowed Whitman to encapsulate and memorialize the deaths in the American Civil War through writing about one person.[83] Roy Morris Jr. wrote to a similar effect, adding that he considered "Lilacs" to be an elegy for Whitman as well as those who had died in the war.[84]

Critics have also noted Whitman's departure from his earlier poetry. Floyd Stovall noted in 1932 that Whitman's "Barbaric yawp" had been "silenced" and replaced by a softer love and "the melancholy chant of death".[85] Ed Folsom argues that although Whitman may have struggled with the fact that his success came from uncharacteristic work, he decided that acceptance was "preferable to exclusion and rejection."[86]

Cluster

James E. Miller considers the cluster to make up a "sustained elegy".[87] The scholar Gay Wilson Allen considered "Hush'd" to be written "hastily" as Whitman's tribute to Lincoln's funeral.[88] Peter J. Bellis agreed, writing that "Hush'd Be the Camps To-Day", as Whitman's first elegy to Lincoln, "seeks both to describe and to perform that burial, to make itself the physical and narrative endpoint of the nation's grief".[89] "Hush'd Be The Camps To-Day" has inaccuracies and what scholar Ted Genoways describes as "stock form"; Whitman was unsatisfied by it.[30] Allen argues that this poem was not "the elegy he [Whitman] felt was needed", and neither was "My Captain!" Throughout the summer Whitman developed his feelings on the assassination as he wrote "Lilacs", which represented the fitting elegy and was one of Whitman's greatest expressive works.[88]

Bellis notes that the poems in Sequel, mainly "Lilacs", switch to focusing on the future. Instead of using Lincoln's burial as an end, "Lilacs" follows his funeral train through "a process of renewal and return" and grapples with grief and death.[89] The literary critic Helen Vendler also noted this progression, writing that the poems go from Lincoln being a "dead commander" (in "Hush'd"), to "fallen cold and dead" (in "My Captain!") to "dust" (in "This Dust").[90] According to the academic F. O. Matthiessen, Whitman's tributes to Lincoln showed how he could give "mythical proportions to his material".[43] Vendler noted the lack of "historical specificity" in all of the elegies.[91]

Lincoln's name is never mentioned in any of the poems in the cluster.[92] Vendler argues this makes the cluster's title "misleading", because only "This Dust" actually comments on Lincoln.[44] Critics have noted the stylistic differences among poems in the cluster; historian Daniel Mark Epstein wrote that it "may seem hard to believe" that the same writer wrote both "Lilacs" and "O Captain! My Captain!".[93] Vendler noted that "Hush'd", "This Dust", and "My Captain!" are instances of Whitman subordinating himself and writing as someone else, whereas "Lilacs" is Whitman speaking.[94] The historian Michael C. Cohen noted that "My Captain" was "carried beyond the limited circulation of Leaves of Grass and into the popular heart" and remade "history in the form of a ballad".[95] Pannapacker considers the cluster part of a larger trend in Whitman's poetry to be more elegiac.[96] The critic Joann P. Krieg argues that the cluster succeeds "by narrowing the scale of emotion to the grief of one individual whose pain reflects that of the nation."[97] Vendler considered that Whitman's Lincoln poems lasted the best of all poetry written on Lincoln from that era.[31]

Notes

- Whitman thought that Lincoln would be buried in Washington on April 19, writing "the shovel'd clods that fill the grave" in "Hush'd Be The Camps To-Day". Lincoln lay in state in Washington and his funeral train departed the city.[30]

References

- Miller 1962, p. 155.

- Kaplan 1980, p. 187.

- Loving 1999, p. 414.

- "CENSORED: Wielding the Red Pen". University of Virginia Library Online Exhibits. Retrieved October 28, 2020. Missing archive link;

- Callow 1992, p. 232.

- Reynolds 1995, p. 340.

- Loving 1999, p. 283.

- Callow 1992, p. 293.

- Peck 2015, p. 64.

- Whitman 1961, pp. 1:68–70.

- Loving 1975, p. 18.

- Loving 1999, pp. 281–283.

- Price & Folsom 2005, p. 91.

- Kummings 2009, p. 420.

- Williams 2010, p. 167.

- Kaplan 1980, p. 259.

- Aaron 1973, p. 69.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 87.

- Griffin, Martin (May 4, 2015). "How Whitman Remembered Lincoln". Opinionator. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 12, 2020. Missing archive link;

- Eiselein, Gregory (1998). LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). 'Lincoln, Abraham (1809–1865)' (Criticism). New York City: Garland Publishing. Retrieved October 12, 2020 – via The Walt Whitman Archive. Missing ISBN;

- Barton 1965, p. 77.

- Barton 1965, pp. 78–79.

- Loving 1999, p. 285.

- Loving 1999, p. 288.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 19.

- Epstein 2004, p. 11.

- Callow 1992, p. 366.

- Barton 1965, p. 108.

- Kummings 2009, p. 20.

- Genoways 2006, p. 534.

- Vendler, Helen (Winter 2000). "Poetry and the Mediation of Value: Whitman on Lincoln". Michigan Quarterly Review. XXXIX (1). hdl:2027/spo.act2080.0039.101. ISSN 2153-3695. Missing archive link;

- Kaplan 1980, p. 300.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 89.

- Blodgett 1953, p. 456.

- Oliver 2005, p. 77.

- Allen 1997, p. 86.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 93.

- Folsom 2019, p. 27.

- Eiselein 1998, p. 395.

- Coyle 1962, p. 22.

- Bellis 2019, p. 81.

- Miller, Cristanne (2009-04-01). "Drum-Taps: Revisions and Reconciliation". Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 26 (4): 171–196. doi:10.13008/2153-3695.1874. ISSN 0737-0679. Missing archive link;

- Matthiessen 1941, p. 618.

- Vendler 1988, p. 132.

- Barton 1965, p. 173.

- Oliver 2005, p. 29.

- Pannapacker 2004, pp. 94–95.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 98.

- Peterson 1994, pp. 138–139.

- Azarnoff, Roy S. (September 1, 1963). "Walt Whitman's Lecture on Lincoln in Haddonfield". Walt Whitman Review. IX: 65–66. Missing identifier (ISSN, JSTOR, etc.);

- Kaplan 1980, p. 31.

- Barton 1965, p. 81.

- Bloom 2009, p. 46.

- Epstein 2004, p. 304.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 91.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 22.

- Loving 1999, p. 305.

- Barton 1965, p. 136.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 94.

- Coyle 1962, p. 143.

- Barton 1965, p. 168.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 101.

- Kaplan 1980, p. 309.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 102.

- Coyle 1962, p. 178.

- Coyle 1962, pp. 201–202.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 88.

- Pannapacker 2004, pp. 21–22.

- Miller 1962, p. 84.

- Oliver 2005, p. 17.

- Parini 2004, p. 378.

- Loving 1999, p. 287.

- Kaplan 1980, p. 30.

- Aaron 1973, p. 70.

- Pannapacker 2004, pp. 86; 89.

- Pannapacker 2004, p. 86.

- Peterson 1994, p. 386.

- Peterson 1994, p. 21.

- Kaplan 1980, p. 301.

- Kaplan 1980, p. 310.

- Seery 2011, p. 123.

- Allen & Folsom 1995, p. 75.

- Killingsworth 2007, p. 63.

- Morris 2000, p. 229.

- Coyle 1962, p. 184.

- Folsom, Ed (1991). "Leaves of Grass, Junior: Whitman's Compromise with Discriminating Tastes". American Literature. 63 (4): 641–663. doi:10.2307/2926872. ISSN 0002-9831. JSTOR 2926872.

- Coyle 1962, p. 281.

- Allen 1997, pp. 197–198.

- Bellis 2019, pp. 72–73.

- Vendler 1988, p. 141.

- Vendler 1988, p. 146.

- Hirschhorn, Bernard. "Memories of President Lincoln (1881–1882)". The Walt Whitman Archive. Retrieved 2021-01-08. Missing archive link;

- Epstein 2004, p. 299.

- Vendler 1988, pp. 132–133.

- Cohen 2015, p. 163.

- Pannapacker 2009.

- Krieg 2009, p. 400.

General sources

- Aaron, Daniel (1973). The Unwritten War: American Writers and the Civil War. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780394465838.

- Allen, Gay Wilson (1997). A Reader's Guide to Walt Whitman. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0488-4.

- Allen, Gay Wilson; Folsom, Ed, eds. (1995). Walt Whitman & the world (PDF). Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press. ISBN 1-58729-004-9. OCLC 44959010.

- Barton, William E. (1965). Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. OCLC 234090069.

- Bellis, Peter J. (2019). "Reconciliation as Sequel and Supplement". In Sten, Christopher; Hoffman, Tyler (eds.). "This mighty convulsion": Whitman and Melville write the Civil War. Iowa City. pp. 69–82. ISBN 978-1-60938-664-1. OCLC 1089839323.

- Blodgett, Harold W. (1953). The Best of Whitman. New York City: Ronald Press Company. OCLC 938884255.

- Bloom, Harold (2009). Walt Whitman. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1549-8.

- Callow, Philip (1992). From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 1566631335. OCLC 644050069.

- Cohen, Michael C. (2015). The Social Lives of Poems in Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9131-5.

- Coyle, William (1962). The Poet and the President: Whitman's Lincoln Poems. New York City: Odyssey Press. OCLC 2591078.

- Eiselein, Gregory (1998). "'O Captain! My Captain!' (1865)". In LeMaster, J. R.; Kummings, Donald D. (eds.). Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. p. 473. ISBN 9780815318767.

- Epstein, Daniel Mark (2004). Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington (1st ed.). New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-45799-4. OCLC 52980509.

- Folsom, Ed (2019). Sten, Christopher; Hoffman, Tyler (eds.). "This Mighty Convulsion": Whitman and Melville Write The Civil War. University of Iowa Press. pp. 23–32. ISBN 978-1-60938-664-1. OCLC 1089839323.

- Genoways, Ted (2006). "Civil War Poems in "Drum-Taps" and "Memories of President Lincoln"". In Kummings, Donald D. (ed.). A Companion to Walt Whitman. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 522–537. ISBN 978-1-4051-2093-7.

- Kaplan, Justin (1980). Walt Whitman, A Life (1st ed.). New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-06-053511-3. OCLC 51984882.

- Killingsworth, M. Jimmie. (2007). The Cambridge introduction to Walt Whitman. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-27529-6. OCLC 153956010.

- Krieg, Joann P. (2009). "Literary Contemporaries". In Kummings, Donald D. (ed.). A Companion to Walt Whitman. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 392–408. ISBN 978-1-4051-9551-5.

- Kummings, Donald D., ed. (2009). A Companion to Walt Whitman. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9551-5.

- Loving, Jerome M. (1975). Civil War Letters of George Washington Whitman. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 0822303310.

- Loving, Jerome (1999). Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21427-7. OCLC 39313629.

- Matthiessen, F. O. (1941). American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199726882. OCLC 640086213.

- Miller, James E. (1962). Walt Whitman. New York City: Twayne Publishers. OCLC 875382711.

- Morris, Roy, Jr. (2000). The better angel : Walt Whitman in the Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512482-0. OCLC 43207497.

- Oliver, Charles M. (2005). Critical Companion to Walt Whitman: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York City: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0858-2.

- Pannapacker, William (February 15, 2004). Revised Lives: Whitman, Religion, and Constructions of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Anglo-American Culture. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-92451-5.

- Pannapacker, William (2009). "The City". In Kummings, Donald D. (ed.). A Companion to Walt Whitman. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 42–59. ISBN 978-1-4051-9551-5.

- Parini, Jay (2004). The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515653-9.

- Peck, Garrett (2015). Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 9781626199736.

- Peterson, Merrill D. (1994). Lincoln in American Memory. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195065701.

- Price, Kenneth; Folsom, Ed, eds. (2005). Re-Scripting Walt Whitman: An Introduction to His Life and Work. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-470-77493-9.

- Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman's America: A Cultural Biography. New York City: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780195170092.

- Seery, John Evan, ed. (2011). A political companion to Walt Whitman. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2655-5. OCLC 707092896.

- Vendler, Helen (1988). The Music of what Happens: Poems, Poets, Critics. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-59152-3.

- Williams, Charles Kenneth (2010). On Whitman. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3433-4. OCLC 650307478.

- Whitman, Walt (1961). Miller, Edwin Haviland (ed.). The Correspondence. Volume 1. New York City: New York University Press. OCLC 471569564.

Further reading

- Grossman, Allen R. (1997). "The Poetics of Union in Whitman and Lincoln". The Long Schoolroom: Lessons in the Bitter Logic of The Poetic Principle. hdl:2027/mdp.39015041310395.

- Rankin, Henry Bascom (1916). Personal Recollections of Abraham Lincoln. G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-7222-8802-3.

- Traubel, Horace (1908). With Walt Whitman in Camden ...: July 16, 1888 – October 31, 1888. New York City: M. Kennerley.

- Whitman, Walt (1906). Memories of President Lincoln: And Other Lyrics of the War. T.B. Mosher.

- Wilson, Edmund (1994). Patriotic gore : studies in the literature of the American Civil War. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31256-0.

- Erkkila, Betsy (1989). Whitman the political poet. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505438-5. OCLC 17548902.