Weierstrass's elliptic functions

In mathematics, Weierstrass's elliptic functions are elliptic functions that take a particularly simple form; they are named for Karl Weierstrass. This class of functions are also referred to as p-functions and generally written using the symbol ℘ (a calligraphic lowercase p; Unicode U+2118, LaTeX \wp). The ℘ functions constitute branched double coverings of the Riemann sphere by the torus, ramified at four points. They can be used to parametrize elliptic curves over the complex numbers, thus establishing an equivalence to complex tori. Genus one solutions of differential equations can be written in terms of Weierstrass elliptic functions. Notably, the simplest periodic solutions of the Korteweg–de Vries equation are often written in terms of Weierstrass p-functions.

Symbol for Weierstrass P function

Definition

Let be two complex numbers that are linear indepent over and let be the lattice generated by those numbers. Then the

-function is defined as follows:

- .

This series converges locally uniformly absolutely in . Often times instead of only is used.

The Weierstrass -function is constructed exactly in such a way that it has a pole of the order two at each lattice point.

Because the sum alone would not converge it is necessary to add the term .[1]

Invariants

In a punctured neighborhood of the origin, the Laurent series expansion of is[2]

where

The numbers g2 and g3 are known as the invariants.

The summations after the coefficients 60 and 140 are the first two Eisenstein series, which are modular forms when considered as functions G4(τ) and G6(τ), respectively, of τ = ω2/ω1 with Im(τ) > 0.

Note that g2 and g3 are homogeneous functions of degree −4 and −6; that is[3],

Thus, by convention, one frequently writes and in terms of the period ratio and take to lie in the upper half-plane. Thus, and .[3]

The Fourier series for and can be written in terms of the square of the nome as

where is the divisor function.[4] This formula may be rewritten in terms of Lambert series.

The invariants may be expressed in terms of Jacobi's theta functions. This method is very convenient for numerical calculation: the theta functions converge very quickly. In the notation of Abramowitz and Stegun, but denoting the primitive periods by , the invariants satisfy

where

and is the period ratio, is the nome, and and are alternative notations.

Special cases

If the invariants are g2 = 0, g3 = 1, then this is known as the equianharmonic case;

g2 = 1, g3 = 0 is the lemniscatic case.[5]

Differential equation

With this notation, the ℘ function satisfies the following differential equation:

where dependence on and is suppressed.[6]

This relation can be quickly verified by forming a linear combination of powers of and to eliminate the pole at . Near we have

and

If we bring everything to one side we have

Since the left hand side has no pole in the period parallelogram it must be constant.[6]

Integral equation

The Weierstrass elliptic function can be given as the inverse of an elliptic integral.

Let

Here, g2 and g3 are taken as constants.

Then one has

The above follows directly by integrating the differential equation.[7]

Modular discriminant

The modular discriminant Δ is defined as the quotient by 16 of the discriminant of the right-hand side of the above differential equation:

This is studied in its own right, as a cusp form, in modular form theory (that is, as a function of the period lattice).

Note that where is the Dedekind eta function.[8]

The presence of 24 can be understood by connection with other occurrences, as in the eta function and the Leech lattice.

The discriminant is a modular form of weight 12. That is, under the action of the modular group, it transforms as

with τ being the half-period ratio, and a,b,c and d being integers, with ad − bc = 1.[9]

For the Fourier coefficients of , see Ramanujan tau function.

The constants e1, e2 and e3

Consider the cubic polynomial equation 4t3 − g2t − g3 = 0 with roots e1, e2, and e3. Its discriminant is 16 times the modular discriminant Δ = g23 − 27g32. If it is not zero, no two of these roots are equal. Since the quadratic term of this cubic polynomial is zero, the roots are related by the equation

The linear and constant coefficients (g2 and g3, respectively) are related to the roots by the equations (see Elementary symmetric polynomial).[10]

The roots e1, e2, and e3 of the equation depend on τ and can be expressed in terms of theta functions. As before, let,

then

Since and , then these can also be expressed as theta functions. In simplified form,

Where is the Dedekind eta function. In the case of real invariants, the sign of Δ = g23 − 27g32 determines the nature of the roots. If , all three are real and it is conventional to name them so that . If , it is conventional to write (where , ), whence , and is real and non-negative.

The half-periods ω1/2 and ω2/2 of Weierstrass' elliptic function are related to the roots

where . Since the square of the derivative of Weierstrass' elliptic function equals the above cubic polynomial of the function's value, for . Conversely, if the function's value equals a root of the polynomial, the derivative is zero.

If g2 and g3 are real and Δ > 0, the ei are all real, and is real on the perimeter of the rectangle with corners 0, ω3, ω1 + ω3, and ω1. If the roots are ordered as above (e1 > e2 > e3), then the first half-period is completely real

whereas the third half-period is completely imaginary

Addition theorems

The Weierstrass elliptic functions have several properties that may be proved:

A symmetrical version of the same identity is

Also[11]

and the duplication formula[11]

unless 2z is a period.

The case with 1 a basic half-period

If , much of the above theory becomes simpler; it is then conventional to write for .

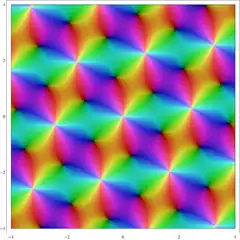

- For a fixed τ in the upper half-plane, so that the imaginary part of τ is positive, we define the Weierstrass ℘ function by

- The sum extends over the lattice {n + mτ | n, m ∈ Z} with the origin omitted.

- Here we regard τ as fixed and ℘ as a function of z; fixing z and letting τ vary leads into the area of elliptic modular functions.

General theory

℘ is a meromorphic function in the complex plane with a double pole at each lattice point. It is doubly periodic with periods 1 and τ; this means that ℘ satisfies

The above sum is homogeneous of degree minus two, and if c is any non-zero complex number,

from which we may define the Weierstrass ℘ function for any pair of periods. We also may take the derivative (of course, with respect to z) and obtain a function algebraically related to ℘ by

where and depend only on τ, being modular forms. The equation

defines an elliptic curve, and we see that is a parametrization of that curve. The totality of meromorphic doubly periodic functions with given periods defines an algebraic function field associated to that curve. It can be shown that this field is

so that all such functions are rational functions in the Weierstrass function and its derivative.

One can wrap a single period parallelogram into a torus, or donut-shaped Riemann surface, and regard the elliptic functions associated to a given pair of periods to be functions defined on that Riemann surface.

℘ can also be expressed in terms of theta functions; because these converge very rapidly, this is a more expeditious way of computing ℘ than the series used to define it.

The function ℘ has two zeros (modulo periods) and the function ℘′ has three. The zeros of ℘′ are easy to find: since ℘′ is an odd function they must be at the half-period points. On the other hand, it is very difficult to express the zeros of ℘ by closed formula, except for special values of the modulus (e.g. when the period lattice is the Gaussian integers). An expression was found, by Zagier and Eichler.[12]

The Weierstrass theory also includes the Weierstrass zeta function, which is an indefinite integral of ℘ and not doubly periodic, and a theta function called the Weierstrass sigma function, of which his zeta-function is the log-derivative. The sigma-function has zeros at all the period points (only), and can be expressed in terms of Jacobi's functions. This gives one way to convert between Weierstrass and Jacobi notations.

The Weierstrass sigma-function is an entire function; it played the role of 'typical' function in a theory of random entire functions of J. E. Littlewood.

Relation to Jacobi's elliptic functions

For numerical work, it is often convenient to calculate the Weierstrass elliptic function in terms of Jacobi's elliptic functions.

The basic relations are[13]

where e1–3 are the three roots described above and where the modulus k of the Jacobi functions equals

and their argument w equals

Typography

The Weierstrass's elliptic function is usually written with a rather special, lower case script letter ℘.[footnote 1]

In computing, the letter ℘ is available as \wp in TeX. In Unicode the code point is U+2118 ℘ SCRIPT CAPITAL P (HTML ℘ · ℘, ℘), with the more correct alias weierstrass elliptic function.[footnote 2] In HTML, it can be escaped as ℘.

| Preview | ℘ | |

|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | SCRIPT CAPITAL P / WEIERSTRASS ELLIPTIC FUNCTION | |

| Encodings | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 8472 | U+2118 |

| UTF-8 | 226 132 152 | E2 84 98 |

| Numeric character reference | ℘ | ℘ |

| Named character reference | ℘, ℘ | |

Footnotes

- This symbol was used already at least in 1890. The first edition of A Course of Modern Analysis by E. T. Whittaker in 1902 also used it.[14]

- The Unicode Consortium has acknowledged two problems with the letter's name: the letter is in fact lowercase, and it is not a "script" class letter, like U+1D4C5 𝓅 MATHEMATICAL SCRIPT SMALL P, but the letter for Weierstrass's elliptic function. Unicode added the alias as a correction.[15][16]

References

- Apostol, Tom M. (1976). Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 9. ISBN 0-387-90185-X. OCLC 2121639.

- Akhiezer, N.I. (1990). Elements of the Theory of Elliptic Functions. American Mathematical Society. p. 12.

- Apostol, Tom M. (1976). Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 14. ISBN 0-387-90185-X. OCLC 2121639.

- Apostol, Tom M. (1990). Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 20. ISBN 0-387-97127-0. OCLC 20262861.

- "Abramowitz and Stegun: Handbook of Mathematical Functions With Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables (AMS55), p.658".

- Apostol, Tom M. (1990). Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 11f. ISBN 0-387-97127-0. OCLC 20262861.

- Knopp, Konrad, 1882-1957. Theory of functions. Mineola, N.Y. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-486-31870-7. OCLC 867774594.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chandrasekharan, K. (Komaravolu), 1920- (1985). Elliptic functions. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 122. ISBN 0-387-15295-4. OCLC 12053023.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Apostol, Tom M. (1976). Modular functions and Dirichlet series in number theory. New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 50. ISBN 0-387-90185-X. OCLC 2121639.

- Abramowitz and Stegun, p. 629

- Lang, Serge, 1927-2005. (1987). Elliptic functions (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 14. ISBN 0-387-96508-4. OCLC 15661205.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Eichler, M.; Zagier, D. (1982). "On the zeros of the Weierstrass ℘-Function". Mathematische Annalen. 258 (4): 399–407. doi:10.1007/BF01453974.

- Korn GA, Korn TM (1961). Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers. New York: McGraw–Hill. p. 721. LCCN 59014456.

- teika kazura (2017-08-17), The letter ℘ Name & origin?, MathOverflow, retrieved 2018-08-30

- "Known Anomalies in Unicode Character Names". Unicode Technical Note #27. version 4. Unicode, Inc. 2017-04-10. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- "NameAliases-10.0.0.txt". Unicode, Inc. 2017-05-06. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene Ann, eds. (1983) [June 1964]. "Chapter 18". Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Applied Mathematics Series. 55 (Ninth reprint with additional corrections of tenth original printing with corrections (December 1972); first ed.). Washington D.C.; New York: United States Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards; Dover Publications. p. 627. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0. LCCN 64-60036. MR 0167642. LCCN 65-12253.

- N. I. Akhiezer, Elements of the Theory of Elliptic Functions, (1970) Moscow, translated into English as AMS Translations of Mathematical Monographs Volume 79 (1990) AMS, Rhode Island ISBN 0-8218-4532-2

- Tom M. Apostol, Modular Functions and Dirichlet Series in Number Theory, Second Edition (1990), Springer, New York ISBN 0-387-97127-0 (See chapter 1.)

- K. Chandrasekharan, Elliptic functions (1980), Springer-Verlag ISBN 0-387-15295-4

- Konrad Knopp, Funktionentheorie II (1947), Dover Publications; Republished in English translation as Theory of Functions (1996), Dover Publications ISBN 0-486-69219-1

- Serge Lang, Elliptic Functions (1973), Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-04162-6

- E. T. Whittaker and G. N. Watson, A Course of Modern Analysis, Cambridge University Press, 1952, chapters 20 and 21

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Weierstrass's elliptic functions. |

- "Weierstrass elliptic functions", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Weierstrass's elliptic functions on Mathworld.

- Chapter 23, Weierstrass Elliptic and Modular Functions in DLMF (Digital Library of Mathematical Functions) by W. P. Reinhardt and P. L. Walker.