Wellness (alternative medicine)

Wellness is a state beyond absence of illness but rather aims to optimize well-being.[1]

The notions behind the term share the same roots as the alternative medicine movement, in 19th-century movements in the US and Europe that sought to optimize health and to consider the whole person, like New Thought, Christian Science, and Lebensreform.[2][3]

The term wellness has also been misused for pseudoscientific health interventions.[4]

History

The term was partly inspired by the preamble to the World Health Organization’s 1948 constitution which said: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”[1] It was initially brought to use in the US by Halbert L. Dunn, M.D. in the 1950s; Dunn was the chief of the National Office of Vital Statistics and discussed “high-level wellness,” which he defined as “an integrated method of functioning, which is oriented toward maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable.”[1] The term "wellness" was then adopted by John Travis who opened a "Wellness Resource Center" in Mill Valley, California in the mid-1970s, which was seen by mainstream culture as part of the hedonistic culture of Northern California at that time and typical of the Me generation.[1] Travis marketed the center as alternative medicine, opposed to what he said was the disease-oriented approach of medicine.[1] The concept was further popularized by Robert Rodale through Prevention magazine, Bill Hetler, a doctor at University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point, who set up an annual academic conference on wellness, and Tom Dickey, who established the Berkeley Wellness Letter in the 1980s.[1] The term had become accepted as standard usage in the 1990s.[1]

In recent decades, it was noted that mainstream news sources had begun to devote more page space to "health and wellness themes".[5]

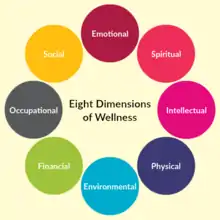

The US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration uses the concept of wellness in its programs, defining it as having eight aspects: emotional, environmental, financial, intellectual, occupational, physical, social, and spiritual.[6] Americans are some of the world’s biggest consumers of wellness products and services. Unfortunately, the same consumer group is also one of the worst affected by lifestyle and chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer and obesity. Recently, wellness product manufacturers, industrial researchers, and medical practitioners observed that there are specific insights that continue to define US consumer spending on wellness. These insights include healthy eating and nutrition, weight management and preventive medicine, fitness, mind and body; the generation factor; and the advent of modern tech such as e-commerce. 1. Healthy Eating and Nutrition - Within America’s wellness economy, healthy eating and nutrition contribute a large portion of the main drivers of American spending on their wellness. (Source 1) - More Americans are moving towards healthy eating and nutrition, which consists of wholegrain, naturally cultivated cereals, pulses, fruits, vegetables, and herbs. (Source 1) - Concurrently, fewer Americans are consuming processed dairy products, processed cereal products, and fast food and opting for organic foods to curb lifestyle and chronic diseases. (Source 1) - According to Statista, the total American sales in organic foods and nutrition products in 2018 stood at $47.86 billion, signalling an increase in wellness spending. (Source 2) 2. Weight Management and Preventive Medicine - According to the Boston Medical Center, Americans spend as much $33 billion annually on weight loss solutions with at least 45 million in the same country going on a diet due to weight-related concerns. (Source 3) - While a large percentage of Americans are generally overweight or obese, only the rich and wealthy individuals made financial commitments to weight management and preventive medicine. (Source 4) - Research organization MarketData tracked the average American spending on weight loss and similar preventive medicine regimens arriving at a staggering $33billion in 2018 alone. (Source 5) 3. Fitness, Mind and Body - The growing number of lifestyle and chronic disease patients has fueled a health and fitness revolution that the International Health, Racquet & Sports Club Association (IHRSA) estimates is worth over $30 billion. (Source 6) - Combined with the increased spending on healthy food and nutrition, the new trend provides insight into why more Americans are interested in activities such as yoga, outdoor races, and gym membership. (Source 6) - The proliferation of budget-friendly gyms alongside those targeting corporate and high net-value individuals seems to be promoting the country’s spending on wellness too. (Source 6) 4. The Generation Factor - Healthy lifestyles and fitness are just as important to the Millennial today as they were to Generation Y Americans a few years ago due to social projection. (Source 7) -The Center for Generational Kinetics stated that the more than 83 millennial Americans not only spend their cash on wellness but also that of their Baby Boomer parents signalling a focus on wellness. (Source 8) -Apart from the distinct food and drink niche wellness products attracting Millennial American spending, technology products such as wearable health gadgets, streaming Apps, and home fitness equipment. (Source 6) 5. Modern Tech - Many Americans interested in making purchases targeting wellness products and services consider technology a major contributing factor due to various data points such as heart rate. (Source 6) -Companies such as Apple, Samsung, FitBit, and Garmin have designed sensors into wearable devices such as smartphones, wristbands, and watches to collect biometric data aligned with wellness and fitness. (Source 6) -Combined with the e-commerce growth, Americans have been spending more than $200 billion annually on the combination of special equipment such as wearable devices and the combination of nutrition and wellness products. (Source 9) -Social and mainstream media has also complemented American spending on tech intended for wellness and healthy lifestyles, as demonstrated by Apps such as Peloton, which stream fitness exercises and gym advice to clients. (Source 9)

Corporate wellness programs

By the late 2000s the concept had become widely used in employee assistance programs in workplaces, and funding for development of such programs in small business was included in the Affordable Care Act.[2] The use of corporate wellness programs has been criticised as being discriminatory to people with disabilities.[7] Additionally, while there is some evidence to suggest that wellness programs can save money for employers, such evidence is generally based on observational studies that are prone to selection bias. Randomized trials provide less positive results and often suffer from methodological flaws.[2]

Criticism

Promotion of Pseudoscience

Wellness is a particularly broad term,[8] but it is often used by promoters of unproven medical therapies, such as the Food Babe[4] or Goop.[8] Jennifer Gunter has criticized what she views as a promotion of over-diagnoses by the wellness community. Goop's stance is that it is "skeptical of the status quo" and "offer[s] open-minded alternatives."[8]

Healthism

Wellness has also been criticized for its focus on lifestyle changes over a more general focus on harm prevention that would include more establishment-driven approaches to health improvement such as accident prevention.[2] Petr Skrabanek has also criticized the wellness movement for creating an environment of social pressure to follow its lifestyle changes without having the evidence to support such changes.[9] Some critics also draw an analogy to Lebensreform, and suggest that an ideological consequence of the wellness movement is the belief that "outward appearance" is "an indication of physical, spiritual, and mental health."[10]

The wellness trend has been criticised as a form of conspicuous consumption.[11]

See also

- Complementary and alternative medicine

- Healthism

- Mindfulness

- Organic food culture

- Salutogenesis

- Wellness tourism

- Workplace wellness

References

- Zimmer, Ben (2010-04-16). "Wellness". The New York Times.

- Kirkland, Anna (1 October 2014). "What Is Wellness Now?". Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 39 (5): 957–970. doi:10.1215/03616878-2813647. ISSN 0361-6878. PMID 25037836.

- Blei, Daniela (4 January 2017). "The False Promises of Wellness Culture". JSTOR Daily.

- Freeman, Hadley (2015-04-22). "Pseudoscience and strawberries: 'wellness' gurus should carry a health warning". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Kickbusch, Ilona; Payne, Lea (1 December 2003). "Twenty-first century health promotion: the public health revolution meets the wellness revolution". Health Promotion International. 18 (4): 275–278. doi:10.1093/heapro/dag418. PMID 14695358.

- "The Eight Dimensions of Wellness". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). 2016.

- Basas, Carrie Griffin, What's Bad About Wellness? (August 1, 2014). Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, Vol. 39, No. 5, 2014. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2478902

- Larocca, Amy. "The Wellness Epidemic". The Cut. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- Appleyard, Bryan (21 September 1994). "Healthism is a vile habit: It is no longer enough simply to be well; we are exhorted to pursue an impossible and illiberal cult of perfection". Independent. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Blei, Daniela (2017-01-04). "The False Promises of Wellness Culture". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 2018-12-09.

- Bearne, Suzanne (1 September 2018). "Wellness: just expensive hype, or worth the cost?". the Guardian. Retrieved 7 September 2018.