Werewoman

In mythology and literature, a werewoman or were-woman is a woman who has taken the form of an animal through a process of lycanthropy. The use of the word "were" refers to the ability to shape-shift but is, taken literally, a contradiction in terms since in Old English the word "wer" means man.[1] This would mean it literally translates to "man-woman".

Werewomen are reported in antiquity and in more recent African folklore, where the phenomenon is sometimes associated with witchcraft, though sources often do not state the animal into which the woman has transformed and it is not necessarily a wolf. In areas where wolves do not exist, other fierce animals may take their place, for instance leopards or hyenas in Africa.[1] Werewomen are distinctive as most legends of lycanthropy involve men, though the process is not restricted solely to men,[2] and if they involve women it is usually in the role of a victim.

The theme of the female werewolf has been used in fiction since Victorian times, while recently the term werewoman has become associated with transgender culture and specifically the fantasy of a forced, but temporary, transformation of a man into a woman.

Historical accounts

In sixth century Lebanon, villages attacked by werewomen were advised by a local holy man to have themselves baptised and to take collective ritual preventive measures.[3]

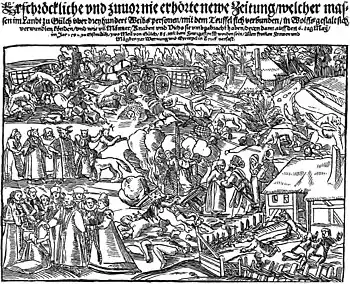

A 1591 broadside, Werewolves of Jurich, printed by Georg Kress, tells the story of the terrorising of the town of Jurich by hundreds of werewolves and depicts a number of male and female werewolves being executed, including some apparently wearing nun's veils.[4]

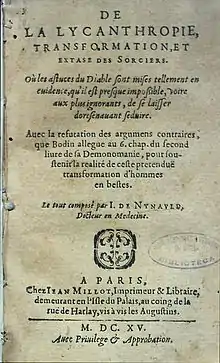

In 1615, French physician Jean de Nynauld reported in De la lycanthropie, transformation et extase des sorciers (On lycanthropy, transformation and ecstasy of witches) the case of a woodsman who had been attacked by a wolf but had managed to cut off its leg. Immediately the wolf turned into a woman who was subsequently burned alive.[5]

Lewis Spence, in his 1920 An Encyclopaedia of Occultism, recorded that in Armenia it was thought that a demon would present himself to a sinful woman and command her to wear a wolf's skin, after donning which she would spend seven years as a wolf during the night, devouring her own and other children and acting generally as a wild beast until the morning when she would resume her human form.[6]

In a legend from Liberia, a lazy husband asks his wife to use her shape-shifting powers to change into a leopard and capture food in order to save him the trouble of hunting. After the wife transforms, she terrorizes her husband with her claws and teeth until he agrees to start hunting again.[7]

Witchcraft

In the early modern world, there was not always a clear separation between the idea of the werewolf and the witch. A werewolf could be male or female but was not necessarily a witch. Some witches, however, could transform themselves into dogs or wolves or enchant those animals, and witch trials sometimes mention witches riding wolves. A werewolf might become so by using a magic ointment and this was similar to the ointment that witches were reputed to use to allow flight. Jean de Nynauld discussed werewolf magic ointments in his 1615 book, though he saw lycanthropy as a form of mental illness rather than a form of magic and believed that the ointments contained hallucinogenic compounds that caused an out of body experience which reinforced the lycanthropic delusion.[4]

In late nineteenth century Asaba, in the Igbo Region of what is now Nigeria, witches were often thought to be werewomen, and a close connection was thought to exist between all women and witchcraft. In one story a mother tries to prevent her son leaving home by transforming herself into a werewoman and is only revealed when the son challenges the "monster or spirit" to reveal its true identity as a human being.[8]

In transgender culture

In transgender slang, the term werewoman has a different meaning of a man who transforms into a woman at night, or possibly once a month on a full Moon.[9] The theme is the subject of fantasy fiction on the internet in stories such as Curse of the Were-Woman: A transformation tale by Dawn Carrington,[10] Gynothrope and Shifters by Maxwell Avoi, and similar stories which together form a genre described as "Reluctant Gender Transformation" or "Gender Transformation Erotica". Such transformations are normally portrayed as forced, either through natural forces such as the phases of the Moon or through magic. In the case of the Carrington story, the actions of a supernatural succubus cause the transformation. The transformation is also forced in the graphic novels Curse of the Were-Woman, written by Jason M. Burns and illustrated by Christopher Provencher, where an inveterate womanizer is cursed by an angry jilted lover and witch, causing him to become a woman at night.[11]

In fiction as werewolves

Werewomen as wolves have appeared in modern popular fiction and the idea was also used in Victorian fiction to explore the issue of women's rights and women's sexuality in, for instance, The Were-Wolf by Clemence Housman, and works by Frederick Marryat.[12] The 1938 short story "Werewoman" by C. L. Moore also dealt with the subject.[13] In comics, Marvel published an edition of their Conan the Barbarian comic in 1974 titled The Warrior and the Were-Woman![14] while a 1976 comic featured a character named Tigra the Were-woman.[15]

References

- "Werewolf" in Green, Thomas A. (Ed.) (1997) Folklore: An encyclopedia of beliefs, customs, tales, music, and art. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, pp. 840-842. ISBN 0-87436-986-X

- "Lycanthropy in Africa" by W. Robert Foran in African Affairs, Vol. 55, No. 219 (Apr., 1956), pp. 124-134.

- "The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity" by Peter Brown in The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 61 (1971), 80-101. (Original source: H. Hilgenfeld, "Syrische Lebensbeschreibung des heiligen Symeons" in H. Lietzmann, Das Leben des heiligen Symeon Stylites (Texte und Untersuchungen XXXII, 4) 1908, pp. 80-187.)

- Davidson, Jane P. (2012) Early modern supernatural: The dark side of European culture, 1400–1700. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, pp. 158-161. ISBN 978-0-313-39344-0

- Robbins, Rossell Hope. (1959) The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. London: Peter Nevill, p. 326.

- "Werewolf" in Spence, Lewis. (1920) An Encyclopaedia of Occultism. New York: University Books, p. 426. Reprint of 1920 original.

- "Shape-Shifting" in Lynch, P.A. and J. Roberts. (2010) African Mythology A to Z. 2nd edition. New York: Chelsea House, pp. 113-114. ISBN 978-1-60413-415-5

- "Myth, Gender and Society in Pre-Colonial Asaba" by Elizabeth Isichei in Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 61, No. 4 (1991), pp. 513-529.

- New Werewoman Handbook: A Manual for the newly transgendered by werewomaniac, BigCloset, 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2013. Archived here.

- Curse of the Were-Woman Dawn Carrington, TG World, 2013. Archived here.

- Curse of the Were-Woman Devil's Due Digital, 2013. Archived here.

- Baird, Jonathan David (12 November 2012). Seductive Beasts: The Female Werewolf in Victorian Literature. The Freehold. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Green, Paul. (2016). Encyclopedia of Weird Westerns: Supernatural and Science Fiction Elements in Novels, Pulps, Comics, Films, Television and Games (2nd ed.). McFarland. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-4766-2402-0.

- Conan the Barbarian #38 ComicVine, 2013. Archived here.

- Marvel Chillers #7 - Jack Kirby cover pencilink, blogspot.co.uk, 22 December 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2013. Archived here.

External links

![]() Media related to Werewolves at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Werewolves at Wikimedia Commons