Westland petrel

The Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica), also known as the Westland black petrel or tāiko, is a moderately large seabird in the petrel family Procellariidae from New Zealand.

| Westland petrel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Procellaria |

| Species: | P. westlandica |

| Binomial name | |

| Procellaria westlandica (Falla, 1946) | |

Identification

The Westland petrel is a stocky looking bird, weighing around 1100g. It is entirely dark blackish-brown, with black legs and feet. Some individuals may have a few white feathers. The bill is pale yellow with a dark tip.[2] The Māori name is tāiko, which also refers to the black petrel, Procellaria parkinsoni.[3]

Geographic distribution and habitat

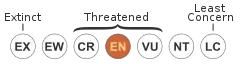

Procellaria westlandica is endemic to New Zealand and is classified as Endangered in the IUCN Red List.[4] It breeds only in a narrow area on the West Coast of the South Island.[5] This breeding range covers an 8 kilometre wide strip[6] between Barrytown and Punakaiki, specifically between the Punakaiki River and Waiwhero (Lawson) Creek[7] and comprises forest-covered coastal foothills[2] either within the Paparoa National Park, on other conservation land, or on land belonging to Forest And Bird.[5] They are one of very few petrel species that still nest on the mainland.[4] The Westland petrel nests in burrows dug 1–2 metres into the hillside, often on a steep slope.[8] Many breeding colonies, particularly on these steep sites, were damaged by landslips and tree damage associated with Cyclone Ita in 2014.[9] There are around 29 colonies of petrel in the breeding territory. Each colony has between 50-1000 burrows.[5] Colonies can be located anywhere from 50–200 meters above sea level.[10] During the breeding season adults may be seen in waters around New Zealand from Cape Egmont to Fiordland in the west, through the Cook Strait, and from East Cape to Banks Peninsula in the east. They also range across areas of the Pacific and Tasman around the Subtropical Convergence.[2] In the non-breeding season, Westland petrels migrate east to South American waters and feed in the Humboldt Current off the coast.[10]

Life cycle and phenology

The Westland petrel spends the majority of its life at sea, only returning to land to breed. They are winter breeders, who arrive at their breeding grounds annually in late March or early April to prepare their burrows for nesting. Colonies are noted to be very vocal around three weeks before nesting, during the time when courtship and mating occur.[11] Petrel form life time pair-bonds. [8] The female lays a single egg between May and June that hatches two months later, between August and September. Both the male and female taking turns incubating the egg. After hatching, the parents care for the chick for about two weeks. After this time the chick is left alone, but is fed at night. If either parent dies, the breeding attempt will fail.[10] The young birds usually don't fly for another two months[12] and moulting occurs in their non-breeding season.[13] For Westland petrels this season falls between October and February, during migration to South America. The immature birds moult prior to older individuals.[10] In total, chick rearing takes between two and four months.[14] After leaving the nesting sites, fledglings may not return for up to 10 years.[15] Beginning in late September to late November, Westland petrel migrate to South American waters and are often found off the coast of Chile.[14] Individuals usually remain solitary during this time, rejoining the colony when the next breeding cycle begins.[10]

Diet and foraging

Petrels are nocturnal and therefore hunt at night, preying primarily on fish, some squid, and less commonly on crustaceans.[16][14] [2]Westland petrels are known to opportunistically scavenge fish from waste discarded by hoki fisheries during their breeding season as it overlaps with the fishing season, switching back to natural foraging at other times.[17] [16] They capture their prey by surface seizing, surface diving, and, less frequently, pursuit plunging.[10] They have been recorded diving up to 8m. [16] Their strong vision allows them to spot prey, and recent studies have shown that smell is also important to petrel foraging, specific odors seeming to attract the birds to certain areas.[14]

Predators, parasites, and diseases

Predators of Westland petrel (stoats, rats and weka) strike during the breeding season when the birds are on land, preying on chicks in open burrows and adults.[18] Feral cats and dogs are also infrequent predators of petrels.[10] None of these predators are considered to be a significant threat to petrel colonies. While not predators, concerns have been raised about the threat of burrow destruction by cattle and goats.[14] They can trample burrows and allow access to predators such as weka, that wouldn't have been able to reach them otherwise.

Little research has been done on disease and parasites in New Zealand seabirds, and there are no diseases recorded to have significance with Westland petrels so far. Avian pox may potentially pose a threat to the petrels, as it has killed a number of black petrel chicks.[10] Other diseases affecting seabirds have been found such as avian cholera in rockhopper penguins (Eudyptes filholi), and avian diphtheria and avian malaria in yellow-eyed penguins (Megadyptes antipodes), none of which have been associated with Westland petrels.

Other information

The Westland Petrel was identified in 1945 after the students of Barrytown School wrote to the then Director of the Canterbury Museum, Robert Falla. They had hear in a radio broadcast about the sooty shearwater/muttonbird, but noticed that the behaviour of the 'mutton birds' in their area was quite different. They also sent Falla a dead bird, and within a few weeks he visited the West Coast. Initially he considered that the West Coast birds were a subspecies of the Black Petrel Procellaria parkinsoni, but they were soon classified as a separate species.[19] [20]

Though they have few natural predators, they threatened by human practices. Powerlines, lights, and commercial fishing post a threat to Westland petrel populations. Power lines have caused the deaths of adult petrels from collision during flight. They are dangerous because they attract the birds and cause disorientation, largely in young petrels. This leads to petrels being grounded, which is a significant issue due to the way that Westland petrels must take flight. When the time comes to leave their breeding sites high in the foothills, Westland petrels climb up the tall trees and throw themselves off to fly. With early grounding, oftentimes the birds will perish from starvation, dehydration, predation, or collision with manmade structures.[10]

Commercial fishing produces competition for food, and sometimes petrels are accidentally captured in fishing nets. This is a prominent risk for Westland petrels due to their tendency to forage from commercial fishery waste, so they are known to interact closely with these vessels.[10]

Westland petrels are interesting in that there is still much that we don't know about the species. Studies are mainly performed during breeding periods due to the petrels’ presence on land, which doesn't fare well for behavioural studies. Very little is known about colonial social behaviours as few studies have been performed. There have been some inquiries about possible vocalisation patterns,[18] but the topic remains largely untouched.

Tāiko Festival

Every year, a festival is held in Punakaiki to celebrate the return of the petrel to its "home". This area is known as the home of the westland petrel, or tāiko (as known by the locals), because it is their only known breeding site. It is a weekend-long festival in April that includes live music, various entertainment activities, and a local market. The festival begins with a viewing of the birds as they fly overhead and make their way to their nests in the mountains at dusk.

References

- BirdLife International. 2018. Procellaria westlandica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22698155A132629809. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22698155A132629809.en. Downloaded on 01 January 2019.

- Heather, Barrie; Robertson, Hugh (2015). The Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand. Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-143-57092-9.

- "tāikoPlay". Māori Dictionary. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- BirdLife International (BirdLifeInternational) (20 August 2018). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Procellaria westlandica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Wood, G. C.; Otley, Helen (September 2013). "An assessment of the breeding range, colony sizes and population of the Westland petrel ( Procellaria westlandica )". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 40 (3): 186–195. doi:10.1080/03014223.2012.736394. ISSN 0301-4223.

- "Westland petrel/tāiko". www.doc.govt.nz. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Wood, G. C.; Otley, H. M. (1 September 2013). "An assessment of the breeding range, colony sizes and population of the Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 40 (3): 186–195. doi:10.1080/03014223.2012.736394. ISSN 0301-4223.

- "Westland petrel | New Zealand Birds Online". nzbirdsonline.org.nz. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- S.M. Waugh, T, Poutart, K-J Wilson. "Storm damage to Westland petrel colonies in 2014 from cyclone Ita" (PDF). Notornis. 2015, Vol. 62: 165–168.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Wilson, K. J., & Coast, W. A review of the biology and ecology and an evaluation of threats to the Westland petrel Procellaria westlandica.

- Baker, A.J.; Coleman, J.D. 1977. The breeding cycle of the Westland black petrel (Procellaria westlandica). Notornis 24: 211–231.

- Best, H. A., & Owen, K. (1976). Distribution of breeding sites of the Westland black petrel (Procellaria westlandica). Notornis, 23(3), 233–242.

- Warham, J. 1990. The petrels: their ecology and breeding systems. Academic Press, London.

- Landers, T. (2012). The behavioural ecology of the threatened Westland Petrel (Procellaria westlandica): from colonial behaviours to their migratory and foraging ecology. Masters thesis. The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

- Brinkley, E. S., Force, M. P., Howell, S. N. G., & Spear, L. B. (2000) Status of the Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica) off South America. Notornis,47(4), 179–182

- Freeman, Amanda N. D. (1998). "Diet of Westland Petrels Procellaria westlandica: the Importance of Fisheries Waste During Chick-rearing". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 98:1: 36–43 – via tandfonline.

- Freeman, A., & Wilson, K. (2002). Westland petrels and hoki fishery waste: opportunistic use of a readily available resource?. Notornis, 49, 139–144.

- Jackson, R. (1958). The westland petrel. Notornis, 7, 230–233.

- Park, Geoff. (1995). Ngā uruora = The groves of life : ecology and history in a New Zealand landscape. Wellington, N.Z.: Victoria University Press. ISBN 0-86473-291-0. OCLC 34798269.

- Norman, Geoff, 1952-. Birdstories : a history of the birds of New Zealand. Nelson, New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-947503-92-5. OCLC 1045734859.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Birdlife species factsheet

- Westland petrel – tāiko Department of Conservation

- Photos and fact file – ARKive

- Petrel festival in Punakaiki