William Cheselden

William Cheselden (/ˈtʃɛsəldən/; 19 October 1688 – 10 April 1752) was an English surgeon and teacher of anatomy and surgery, who was influential in establishing surgery as a scientific medical profession. Via the medical missionary Benjamin Hobson, his work also helped revolutionize medical practices in China and Japan in the 19th century.

William Cheselden | |

|---|---|

William Cheselden | |

| Born | 19 October 1688 |

| Died | 10 April 1752 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | lithotomy |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | surgery |

| Institutions | St George's Hospital |

| Influences | William Cowper |

| Influenced | Alexander Monro Samuel Sharp |

Life

Cheselden was born at Somerby, Leicestershire. He studied anatomy in London under William Cowper (1666–1709),[1] and began lecturing anatomy in 1710. That same year, he was admitted to the London Company of Barber-Surgeons, passing the final examination on 29 January 1711.

He was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1712 and the following year saw the publishing of his Anatomy of the Human Body, which achieved great popularity becoming an essential study source for students, lasting through thirteen editions,[1] mainly because it was written in English instead of Latin as was customary.

In 1718 he was appointed an assistant surgeon at St Thomas' Hospital in London, becoming full surgeon in 1719[1] or 1720 where his specialisation of the removal of bladder stones resulted in the increase in survival rates. Afterwards, he was appointed surgeon for the stone at Westminster Infirmary and surgeon to Queen Caroline. He also improved eye surgery, developing new techniques, particularly in the removal of cataracts. Cheselden was selected as a surgeon at St George's Hospital upon its foundation in 1733.

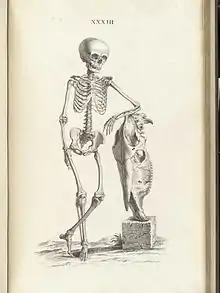

In 1733 he published Osteographia or the Anatomy of Bones, the first full and accurate description of the anatomy of the human skeletal system.

Cheselden retired from St Thomas' in 1738 and moved to the Chelsea Hospital. His abode is listed as "Chelsea College" on the 1739 Royal Charter for the Foundling Hospital, a charity for which he was a founding governor.

In 1744 he was elected to the position of Warden of the Company of Barber-Surgeons, and had a role in the separation of the surgeons from the barbers and to the creation of the independent Company of Surgeons in 1745, an organisation that would become later the famous Royal College of Surgeons of England.

He died at Bath in 1752.

First surgical recovery from blindness

Cheselden is credited with performing the first known case of full recovery from blindness in 1728, of a blind 13-year-old boy.[2] Cheselden presented the celebrated case of a boy of thirteen who gained his sight after removal of the lenses rendered opaque by cataract from birth. Despite his youth, the boy encountered profound difficulties with the simplest visual perceptions. Described by Cheselden:

When he first saw, he was so far from making any judgment of distances, that he thought all object whatever touched his eyes (as he expressed it) as what he felt did his skin, and thought no object so agreeable as those which were smooth and regular, though he could form no judgment of their shape, or guess what it was in any object that was pleasing to him: he knew not the shape of anything, nor any one thing from another, however different in shape or magnitude; but upon being told what things were, whose form he knew before from feeling, he would carefully observe, that he might know them again;[3]

Works

Cheselden is famous for the invention of the lateral lithotomy approach to removing bladder stones, which he first performed in 1727.[1] The procedure had a short duration (minutes instead of hours) and a low mortality rate (approximately 50%). Cheselden had already developed in 1723 the suprapubic approach, which he published in A Treatise on the High Operation for the Stone. In France, his works were developed by Claude-Nicolas Le Cat.

He also effected a great advance in ophthalmic surgery by his operation, iridectomy, described in 1728, to treat certain forms of blindness by producing an artificial pupil. Cheselden also described the role of saliva in digestion. He attended Sir Isaac Newton in his last illness and was an intimate friend of Alexander Pope and of Sir Hans Sloane.[1]

References

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cheselden, William". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 89.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cheselden, William". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 89. - "The New Yorker: From the Archives: Content". Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- An Account of Some Observations Made by a Young Gentleman, Who Was Born Blind, or Lost His Sight so Early, That He Had no Remembrance of Ever Having Seen, and Was Couch'd between 13 and 14 Years of Age. By Will. Cheselden. Philosophical Transactions, Vol. 35. (1727–1728), pp. 447–450.

Sources

- R. H. Nichols and F A. Wray, The History of the Foundling Hospital (London: Oxford University Press, 1935), p. 353.

- Ballesteros Sampol, Juan José (September 2007). "[William Cheselden: singular lithotomist and great illustrator of the XVIII Century]". Arch. Esp. Urol. 60 (7): 723–729. doi:10.4321/s0004-06142007000700001. PMID 17937331.

- Mark, Harry H. (February 2003). "The strange report of Cheselden's iridotomy". Arch. Ophthalmol. 121 (2): 266–268. doi:10.1001/archopht.121.2.266. PMID 12583795.

- Weygand, Z. (2000). "[From the experience of Cheselden (1728) to the experiences of Dr. Guillie on contagious ophthalmia (1819–1820). Different methods of using those who were blind at birth as point of proof.]". Histoire des sciences médicales. 34 (3): 295–304. PMID 11640524.

- Sanders, M. A. (November 1999). "William Cheselden: anatomist, surgeon, and medical illustrator". Spine. 24 (21): 2282–2289. doi:10.1097/00007632-199911010-00019. PMID 10562998.

- Guest, J. (August 1997). "William Cheselden (1688–1752): humane anatomist and master surgeon". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 67 (8): 524–527. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb02031.x. PMID 9287918.

- Hausmann, H. (March 1989). "[William Cheselden (1688–1752). On the 300th birthday of the English surgeon]". Zeitschrift für Urologie und Nephrologie. 82 (3): 151–154. PMID 2658419.

- "William Cheselden tercentenary". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 71 (2 Suppl): 26–29. March 1989. PMID 2653161.

- Dahl, D. S. (May 1968). "William Cheselden (1688–1752)". Investigative Urology. 5 (6): 627–629. PMID 4914853.

- Brackett, A. S. (June 1956). "William Cheselden, 1688–1752". Connecticut Medicine. 20 (6): 467–468. PMID 13317466.

- Russell, K. F. (1954). "The osteographia of William Cheselden". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 28 (1): 32–49. PMID 13141000.

- Cope, Zachary; William Cheselden, 1688–1752. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone, 1953.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Cheselden. |

- William Cheselden (1666–1709). Surgical Tutor.

- Cheselden, Wm: Osteographia or the Anatomy of the Bones. Scanned pages of the original work. Historical Anatomies in the Web. US National Library of Medicine.

- Complete scanned copy of the Ostepgraphia in the public domain at Biu Sante.

- The Anatomy of the Human Body (1750) at the Internet Archive.

- Accuracy and Elegance in Cheselden's Osteographia (1733) article by Monique Kornell, including gallery and comprehensive links to public domain online copies.

- Selected images from Anatomy of the Humane Body From The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Digital Library