William Hepworth Dixon

William Hepworth Dixon (30 June 1821 – 26 December 1879) was an English historian and traveller. He was also active in organizing London's Great Exhibition of 1851.

Early life

He was born on 30 June 1821, at Great Ancoats in Manchester. His father was Abner Dixon of Holmfirth and Kirkburton in the West Riding of Yorkshire, his mother Mary Cryer. His uncle was the reform campaigner and manufacturer Elijah Dixon. His boyhood was passed in the hill country of Over Darwen, under the tuition of his grand-uncle, Michael Beswick. As a lad he became clerk to a merchant named Thompson at Manchester.[1]

Man of letters

Early in 1846 Dixon decided on a literary career. He was for two months editor of the Cheltenham Journal. While at Cheltenham he won two principal essay prizes in Madden's Prize Essay Magazine. In the summer of 1846, on the recommendation of Douglas Jerrold, he moved to London. He entered the Inner Temple, but was not called to the bar until 1 May 1854. He never practised as a barrister.[1]

About 1850 Dixon was appointed a deputy-commissioner of the Great Exhibition of 1851. He helped to start more than one hundred out of three hundred committees then formed. After a long tour in Europe Dixon became, in January 1853, editor of The Athenaeum, to which he had been a contributor for some years.[1] He remained editor until 1869.[2]

Traveller

.jpg.webp)

In 1861 Dixon travelled in Portugal, Spain, and Morocco. In 1863 he travelled in the East, and on his return helped to found the Palestine Exploration Fund; Dixon was an active member of the executive committee, and eventually became chairman. In 1866 he travelled through the United States, going as far west as Salt Lake City. During this tour he discovered a collection of state papers, originally Irish, in the Public Library at Philadelphia. They had been missing since the time of James II, and on Dixon's suggestion were given to the British government.[1][3]

In autumn 1867 Dixon travelled through the Baltic provinces. In the latter part of 1869 he travelled for some months in Russia. During 1871 he was mostly in Switzerland. Shortly afterwards he was sent to Spain on a financial mission by a council of foreign bondholders. On 4 October 1872 he was created a knight commander of the Crown by Kaiser Wilhelm I. In the September 1874 he travelled through Canada and the United States; in the latter part of 1875 he travelled once more in Italy and Germany.[1]

Politician and activist

At the general election of 1868 Dixon declined an invitation to stand for Marylebone, though he frequently addressed political meetings. In August 1869 he resigned the editorship of the Athenæum. Soon afterwards he was appointed justice of the peace for Middlesex and Westminster.[1]

Dixon took a leading part in establishing the Shaftesbury Park Estate and other centres of improved dwellings for the labouring classes. He was a member of the first School Board for London (1870). During the first three years of the School Board's existence Dixon's labours were extensive. In direct opposition to Lord Sandon he succeeded in carrying a resolution which thenceforth established military drill in all rate-paid schools in the metropolis.[1]

About 1873 Dixon began a movement for opening the Tower of London free of charge to the public. To this proposal the prime minister Benjamin Disraeli assented, and on public holidays Dixon personally conducted crowds of working men through the building.[1]

Later life

Dixon lost most of his savings, invested in Turkish stock. On 2 October 1874 his house near Regent's Park, 6 St. James's Terrace, was completely wrecked by an explosion of gunpowder on Regent's Canal. He lost his eldest daughter, and his eldest son, William Jerrold Dixon, to a sudden death in Dublin, on 20 October 1879.[1] However, his youngest daughter, Ella Hepworth Dixon, became a writer, editor and novelist of some repute.[4]

Dixon was a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, of the Society of Antiquaries of London, of the Pennsylvania Society, and of other learned associations. Before the close of 1878 he visited Cyprus. There a fall from his horse broke his shoulder-bone, and he was left an invalid. He was revising the proof sheets of the concluding volumes of Royal Windsor and on Friday 26 December 1879, made an effort to finish the work. He died in his bed on the following morning from a seizure. On 2 January 1880 he was buried in Highgate cemetery.[1]

Works

Before he was of age Dixon wrote a five-act tragedy, The Azamoglan, which was privately printed. In 1842–3 he wrote articles signed W. H. D. in the North of England Magazine. In December 1843 he first wrote under his own name in Douglas Jerrold's Illuminated Magazine. He became a contributor to the Athenæum and the Daily News.[1]

Dixon was criticised for inaccuracy as an author.[1]

Social issues

In the Daily News Dixon published a series of startling papers on The Literature of the Lower Orders, which may have suggested Henry Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor. Another series of articles, descriptive of the London Prisons, led to his work, John Howard and the Prison World of Europe, which appeared in 1849, and though declined by many publishers then passed through three editions.[1]

History and biography

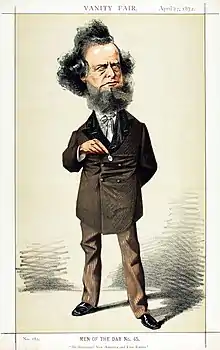

Dixon as caricatured by Adriano Cecioni in Vanity Fair, April 1872

Dixon's Life of William Penn was published in 1851; in a supplementary chapter "Macaulay's charges against Penn",’ eight in number, were elaborately answered. Thomas Babington Macaulay never took notice of these criticisms.[1]

In 1852 Dixon published a life of Robert Blake, Admiral and General at Sea, based on Family and State Papers. In 1854 he began researches on Francis Bacon. He had leave, through Lord Stanley and Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, to inspect the "State Papers", until then jealously guarded from the general view by successive secretaries of state. He published four articles criticising John Campbell's Life of Bacon in the Athenæum for January 1860. These were enlarged and republished as The Personal History of Lord Bacon from Unpublished Papers in 1861. He published separately as a pamphlet in 1861 A Statement of the Facts in regard to Lord Bacon's Confession, and a more elaborate volume called The Story of Lord Bacon's Life, 1862. Dixon's books on Bacon have not been valued by scholars.[1]

Some of Dixon's papers in the Athenæum led to the publication of the Auckland Memoirs and of Court and Society, edited by the Duke of Manchester. To the latter he contributed a memoir of Queen Catherine.[1]

In 1869 Dixon brought out the first two volumes of Her Majesty's Tower, which he completed two years afterwards by the publication of the third and fourth volumes. While in Spain Dixon wrote most of his History of Two Queens, i.e. Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn. The work expanded into four volumes, the first half of which was published in 1873, containing the life of Catherine of Aragon, and the second half in 1874, containing the life of Anne Boleyn. In 1878 appeared the first two volumes of his four-volumed work Royal Windsor.[1]

Religion

Dixon's book Spiritual Wives (1868), treating partly Mormonism, was accused of indecency. He brought an action for libel against the Pall Mall Gazette which had made the charge in a review of Free Russia. He obtained a verdict for one farthing (29 November 1872).[1]

Travel books

In 1865 Dixon published The Holy Land, a picturesque handbook to Palestine. In 1867 he published his ‘New America.’ It passed through eight editions in England, three in America, and several in France, Russia, Holland, Italy, and Germany. In 1872 he published The Switzers. In March 1875 he wrote on North America in The White Conquest. Other books of travel were Free Russia (1870), and British Cyprus (1879).[1]

Novels

In 1877 Dixon published his first romance, in 3 volumes: Diana, Lady Lyle. Another three-volume work of fiction followed in 1878: Ruby Grey.[1]

Other works

During a panic in 1851 Dixon brought out an anonymous pamphlet, The French in England, or Both Sides of the Question on Both Sides of the Channel, arguing against the possibility of a French invasion. In 1861 he edited the Memoirs of Sydney, Lady Morgan, who had appointed him her literary executor. During 1876 he wrote in the Gentleman's Magazine "The Way to Egypt", as well as two other papers in which he recommended the government to purchase from Turkey its Egyptian suzerainty.[1]

In 1872 under the pseudonym Onslow Yorke he published an exposé of the International Workingmen's Association The Secret History of "The International" Working Men's Association, which following the Bolshevik Revolution was republished by the British far right in 1921.

Family life

Dixon's daughter, Ella Nora Hepworth Dixon, best known as Margaret Wynman, was a novelist and journalist.

References

- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- With them was found the original manuscript of the Marquis of Clanricarde's ‘Memoirs’ from 23 October 1641 to 30 August 1643, which were supposed to have been destroyed, and of which mention had been made in Hardy's Report on the Carte and Carew Papers.

- ODNB entry for Ella Hepworth Dixon, by Nicola Beauman: Retrieved 25 July 2013. Pay-walled.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Dixon, William Hepworth". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Dixon, William Hepworth". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: William Hepworth Dixon |

- Works by William Hepworth Dixon at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Hepworth Dixon at Internet Archive

- William Penn: an historical biography William Hepworth Dixon, 1851, (Blanchard & Lea, London)

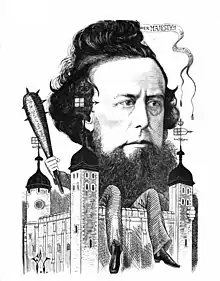

- Anonymous (1873). Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day. Illustrated by Frederick Waddy. London: Tinsley Brothers. pp. 34–35. Retrieved 6 January 2011.