William Strickland (architect)

William Strickland (November 1788 – April 6, 1854), was a noted architect and civil engineer in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Nashville, Tennessee. A student of Benjamin Latrobe and mentor to Thomas Ustick Walter, Strickland helped establish the Greek Revival movement in the United States. A pioneering engineer, he wrote a seminal book on railroad construction, helped build several early American railroads, and designed the first ocean breakwater in the Western Hemisphere.[1]

William Strickland | |

|---|---|

1829 portrait of Strickland by John Neagle. | |

| Born | William Strickland November , 1788 |

| Died | April 6, 1854 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Rachel McCulloch Trenchard |

| Children | 5 |

| Parent(s) | John Strickland Elizabeth Campbell |

| Buildings | Second Bank of the United States, Merchants' Exchange |

Life and career

Strickland was born in the Navesink section of Middletown Township, New Jersey, and moved with his family to Philadelphia as a child.[2] In his youth, he was a landscape painter, illustrator for periodicals, theatrical scene painter, engraver, and pioneer aquatintist. His Greek Revival designs drew much inspiration from the plates of The Antiquities of Athens.

Strickland and Latrobe competed to design the Second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia (1819–1824), a competition that called for "chaste" Greek style. Strickland, who was still copying classical prototypes at this point, won with an ambitious design modeled on the iconic Parthenon of Athens. Proud of the building, Strickland had it included in the background of his 1829 portrait by Philadelphia society painter John Neagle.

The oldest building designed by W. Strickland, which is preserved to this day, is the Holy Trinity Romanian Orthodox Church, located at 222-230 Brown Street Philadelphia (Northern Liberties Area), formerly known as St. John's Episcopalian Church. An anonymous report from its consecration, published on September 21, 1816, in Relf’s Philadelphia Gazette and Daily Advertiser, describes the church as a “neat and elegant edifice” whose “design was given by Mr. William Strickland, of this city,” and whose “execution has done justice to the taste of the Architect.” (Jeffrey. A. Cohen, 1983).

Strickland's evolving talent and confidence is seen in the later Merchants' Exchange (1832–34). Also in Philadelphia, the Merchant Exchange is built on classical example — for example, the cupola is based on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates — but is a unique building styled to fit the site. It was to be located on a triangular plot at the intersection of two major thoroughfares between the waterfront and the business district. The elegant, curved east façade faces the waterfront, and reflects the carriage and foot traffic that would have been circulating in front of the building. This elevation is unique — Greek Revival, but modern — while a more staid and formal elevation can be found on the west side, facing Third Street. In the same year he designed the Merchants' Exchange, 1832, Strickland entered a project in the competition for Philadelphia's Girard College, which won the second prize.[3]

Strickland's 1836 National Mechanic Bank at 22 South 3rd Street, set on a narrow plot between two taller neighbors, has strong, square pilasters to support the portico and ornate stone carving at their tops to defend the building against its taller and bulkier neighbors. One of Strickland's last Philadelphia designs and among his smallest, the building is now occupied by National Mechanics Bar and Restaurant.

Strickland also executed works in other styles, including very early American work in the Gothic Revival style, including his Masonic Hall (1808–11, burned 1819) and his Saint Stephen's Church (1823), both in Philadelphia. He also made use of Egyptian, Saracenic and Italianate styles. He later moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where his Egyptian-influenced design of the First Presbyterian Church (now the Downtown Presbyterian Church) was controversial but today is widely recognized as a masterpiece and an important evocation of the Egyptian Revival style.

Strickland was also a civil engineer[1] and one of the first to advocate the use of steam locomotives on railways. Some argue that Strickland's observations made during visits to England in the 1820s were highly influential in the transfer of railway technology to the United States: "William Strickland's Reports are the starting point of American railway engineering, and represent the state of knowledge as the first railways were planned in that country."[4][5] In 1835, the Wilmington and Susquehanna Railroad hired him to survey a route from Wilmington, Delaware, to Charlestown, Maryland. Later that year, he was named chief engineer of the Delaware and Maryland Railroad.[6] Strickland designed and built the Delaware Breakwater, the first breakwater in the Americas and the third in the world.[7]

Several architects and engineers of note began or developed their careers in Strickland's employ, including Thomas Ustick Walter, Gideon Shryock and John Trautwine.[8]

Strickland died in Nashville and is buried within the walls of his final, and arguably greatest work, the Tennessee State Capitol. A cenotaph for him exists in the family plot in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.[9]

Selected works

Philadelphia buildings

- Masonic Hall, Philadelphia (1808–11, burned 3 March 1819).

- Holy Trinity Romanian Orthodox Church, Philadelphia, also known as the former St. John's Episcopal Church (1815–16).

- Second Bank of the United States, Philadelphia (1819–24).

- St. Stephen's Episcopal Church, Philadelphia (1822–23).

- Second Chestnut Street Theatre - 1822 - 1856 (burned)

- Musical Fund Hall, The Musical Fund Society, Philadelphia - 1824, (substantially altered).

- Wyck House - 1824 (rearranged its interior)

- Triumphal Arches for Lafayette's visit - 1824

- Second Congregation Mikveh Israel Synagogue, Philadelphia - 1825, (demolished).

- United States Naval Asylum, Philadelphia - 1826–33, (now condominiums).

- Restoration of the tower of Independence Hall, Philadelphia - 1828.

- First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia, - 1828

- University of Pennsylvania (9th Street buildings), Philadelphia - 1829[1]

- Arch St. Theater - 1829 (1863 damaged by fire, demolished 1936)

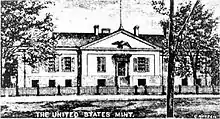

- Second Philadelphia Mint, Philadelphia - 1829–33 (demolished 1902).

- Blockley Almshouse - 1835 (demolished 1920s - 1959)

- Merchants' Exchange, Philadelphia 1832–34.

- Mechanics National Bank - 1837

Buildings elsewhere

- Immanuel Episcopal Church on the Green, New Castle, Delaware (1822)

- Delaware Breakwater and Lighthouse, Lewes, Delaware (1826-1840, lighthouse decomissioned in 1903, demolished in 1956)

- College of Charleston, Main Building (now Randolph Hall), Charleston, South Carolina (1828, extensively altered 1850).

- Nathanael Greene Monument, Savannah, Georgia (1830).

- U.S. Branch Mint, Charlotte, North Carolina (1835, moved to new location 1930s). Now Mint Museum of Art.

- U.S. Branch Mint, Dahlonega, Georgia (1835, burned 1878).

- U.S. Branch Mint, New Orleans, Louisiana (1835–38).

- Providence Athenaeum, Providence, Rhode Island (1837–38).

- Sussex County Courthouse, Georgetown, Delaware (1837)

- Grace Church, Keswick, Virginia (1848–55).

- St. John's Episcopal Church, Salem, NJ (1838).[11]

Tennessee

- Tennessee State Capitol, Nashville, Tennessee (1845–59).

- Second Presbyterian Church, Nashville, Tennessee (1846, demolished 1979).

- Wilson County Courthouse, Lebanon, Tennessee (1848, burned 1881).

- First Presbyterian Church, Nashville, Tennessee (1848–49).

- Belmont Mansion, Nashville, Tennessee (1849–53). Formerly Acklen Hall during Ward-Belmont College years, Belmont University(This is debated).

Gallery

Masonic Hall, Philadelphia (1808–11, burned 1819).

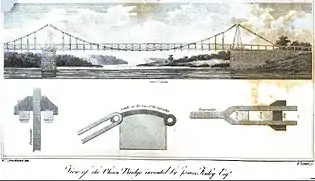

Masonic Hall, Philadelphia (1808–11, burned 1819). "View of the Chain Bridge invented by James Finley Esq.", William Strickland, delineator. The Port Folio, June 1810.

"View of the Chain Bridge invented by James Finley Esq.", William Strickland, delineator. The Port Folio, June 1810. Saint Stephen's Episcopal Church, Philadelphia, PA (1822–23).

Saint Stephen's Episcopal Church, Philadelphia, PA (1822–23)..jpg.webp) "G. Stephenson's Patent Locomotive Engine." William Strickland, artist and engraver (1826).

"G. Stephenson's Patent Locomotive Engine." William Strickland, artist and engraver (1826). United States Naval Asylum, Philadelphia, PA (1826–33)

United States Naval Asylum, Philadelphia, PA (1826–33) University of Pennsylvania (9th Street buildings), Philadelphia, PA (1829, demolished).

University of Pennsylvania (9th Street buildings), Philadelphia, PA (1829, demolished).

United States Mint, Philadelphia, PA (1829–33, demolished 1902).

United States Mint, Philadelphia, PA (1829–33, demolished 1902). United States Mint, Charlotte, NC (1835, moved to new location 1930s). Now Mint Museum of Art.

United States Mint, Charlotte, NC (1835, moved to new location 1930s). Now Mint Museum of Art. United States Mint, New Orleans, LA (1835–38). Now Louisiana State Museum.

United States Mint, New Orleans, LA (1835–38). Now Louisiana State Museum. Providence Athenaeum, Providence, RI (1837–38).

Providence Athenaeum, Providence, RI (1837–38). Tennessee State Capitol (1845–59), interior.

Tennessee State Capitol (1845–59), interior. First Presbyterian Church, Nashville, TN (1848–49).

First Presbyterian Church, Nashville, TN (1848–49). Grace Church, Keswick, VA (1848–55).

Grace Church, Keswick, VA (1848–55). Belmont Mansion, Nashville, TN (1849–53). Now Acklen Hall, Belmont University.

Belmont Mansion, Nashville, TN (1849–53). Now Acklen Hall, Belmont University.

Notes

- "University of Pennsylvania". World Digital Library. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- Strickland, William (1788 - 1854), Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. Accessed July 26, 2018. "Born in Navesink, NJ, to John and Elizabeth Strickland, William Strickland had the advantage of a master carpenter father who moved the family to Philadelphia in c. 1790 and became a charter member of the Practical House Carpenters' Society in 1811."

- Bruce Laverty, Michael J. Lewis, and Michelle Taillon Taylor, Monument to Philanthropy: The Design and Building of Girard College, 1832-1848 (Philadelphia: Girard College, 1998), pp. 39-41; 46-47; 56-57

- Strickland's Report

- William Levitt (Early Railways 3, 2006)

- "1835 (June 2004 Edition)" (PDF). PRR CHRONOLOGY. The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society. June 2004. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- DelSordo, Stephen G. (August 1988). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: National Harbor of Refuge and Delaware Breakwater Harbor Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/25248

- "William Strickland". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- William Strickland Tomb from Flickr.

- Minutes of the Vestry of St. John's Episcopal Church, Salem, NJ

References

- Gilchrist, Agnes Addison (1950). William Strickland: Architect and Engineer, 1788-1854. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- "Strickland, William (1788-1854)" Philadelphia Architects And Buildings. Available: <http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/25248>