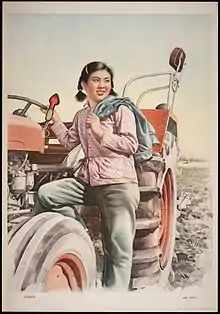

Women in agriculture in China

Women in agriculture in China make up a diverse group of women who support agricultural activities in their country. Because China is a large country, rural women should not be considered a monolithic group, but instead have different strategies for success based on group or family relationships.[1]

History

Based on Confucian principals, farming was an expression of "moral worth" for men of all social classes in China while weaving and creating textiles was a way for women to show their worth in society.[2] Traditionally, "women were subordinated to men,"[3] and although men had primary responsibility for the farm, women were certainly involved in farming in the early Chinese economy.[4] During the Han Dynasty, women's contributions to agriculture in China increased, most likely due to the innovation and popularization of the pit-farming method.[5] Textile creation, which relied on help and silk, was also considered by early Chinese to be an "agricultural product" rather than a separate craft.[5]

Prior to the Chinese Revolution, small family farms where women contributed to farm and house work, made up the majority of agriculture in China.[6] Women's contributions to the family farm were often overlooked by early twentieth century scholars because women's work was not recognized by men and not reported in economic surveys.[7] Women also did not have land rights in pre-revolutionary China.[7]

As China went through the reform, the farm sector became a powerful force in the economy.[8] The Constitution of the People's Republic of China makes the provision that women are equal to men, but in practice, traditional gender roles have persisted where men are considered "superior to women."[9] After 1949, the Chinese government strongly encouraged women's participation in agriculture.[10]

During the 1980s, China went through a "decollectivization of agriculture," as part of the household responsibility system (HRS) which caused individual households to "undertake a vast majority of agricultural production."[11] HRS also contributed to a greater amount of commercialization in Chinese agriculture.[12] Women's ability to own land was again affected by the HRS, which began to discourage women who had married from filing readjustments to land-ownership, making married women "effectively landless."[13]

By the mid 1990s, 80% of Chinese women lived in rural areas and were doing approximately 70 to 80 percent of the farm work, in addition to caring for family members.[14] After this, however, women's contribution to farm work began to fall and by 2000 had dropped below 51 percent.[15] During this time period, village governments counted women as fully "part of the village labor force," and did not keep separate records for men's and women's labor.[16] The number of women involved in migrant farm work has risen steadily since the 1980s, only 1% of women were earning money as migrant workers, in 2000 that number rose to 7%.[17] In 2000, women made up 59% of livestock activities.[18]

Modern farms

Today, agriculture remains a "dominant occupation in China."[19] China also plans to register all landowners by 2018, a plan which may actually disenfranchise women.[20] However, 13 different provinces of China "issued policy documents that require the protection of women's equal rights to land in the registration process."[20] The problem of women's land rights involves the fact that most married women's land rights "are retained in their natal households."[21] In addition, a survey taken after 2012 found that "only 17.1 percent of existing land contracts and 38.2 percent of existing land certificates include women's names.[22]

Women entrepreneurs in agriculture have been enabled by new market forces to start their own businesses.[23] Shared Harvest, opened in 2012 by Shi Yan, is an organic farm and one of the first farms to take part in the Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) model.[24] Trends towards buying CSA foods, such as consumers wanting more organic produce or rejecting the industrialization of agriculture, has helped grow more CSA farms in China.[25]

References

Citations

- Zhang et al. 2006, p. 2.

- Bray, Francesca (2013). Technology, Gender and History in Imperial China. New York: Routledge. pp. 79–80. ISBN 9780415639569.

- "Imperial China". UNM. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Hinsch 2010, p. 71.

- Hinsch 2010, p. 72.

- Bossen 2000, p. 172.

- Bossen 2000, p. 173.

- Zhang et al. 2006, p. 11.

- The International Rice Research Institute 1985, p. 69.

- Agarwal 2007, p. 4262.

- De Brauw 2003, p. 3.

- Agarwal 2007, p. 4261.

- Agarwal 2007, p. 4265.

- Wang, Jiaxiang (22 September 1996). "What Are Chinese Women Faced With After Beijing?". Feminist Studies.

- De Brauw 2003, p. 10.

- Bossen 2000, p. 175.

- Zhang et al. 2006, p. 14.

- Zhang et al. 2006, p. 25.

- Dasgupta, Sukti; Matsumoto, Makiko; Xia, Cuntao (May 2015). Women in the Labour Market in China (PDF) (Report). p. 10. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Hanstad, Tim (3 November 2014). "Depriving Women Farmers of Land Rights Will Set Back China". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Li & Yin-Sheng 2006, p. 622.

- Mack, Jessica (8 March 2012). "Women Losing Land Rights in China". Ms. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Agarwal 2007, p. 4263.

- Yu, Katrina (25 November 2015). "Meet the Woman Leading China's New Organic Farming Army". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Hitchman, Judith (11 June 2015). "Community Supported Agriculture Thriving in China". Agri Cultures. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

Sources

- Agarwal, Ritu (October 2007). "Women Farmers in China's Commercial Agrarian Economy". Economic and Political Weekly. 42 (42): 4261–4267. JSTOR 40276578.

- Bossen, Laurel (2000). "Women Farmers, Small Plots, and Changing Markets in China". In Spring, Anita (ed.). Women Farmers and Commercial Ventures: Increasing Food Security in Developing Countries. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1555878695.

- De Brauw, Alan (10 July 2003). Are Women Taking Over the Farm in China? (Report). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.294.2390.

- Hinsch, Bret (2010). Women in Early Imperial China (2nd ed.). New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742568242.

- The International Rice Research Institute (1985). Women in Rice Farming: Proceedings of a Conference on Women in Rice Farming Systems. Brookfield, Vermont: Gower Publishing Company Limited. ISBN 0566007215.

- Li, Yang; Yin-Sheng, Xi (November 2006). "Married Women's Rights to Land in China's Traditional Farming Areas". Journal of Contemporary China. Routledge. 15 (49): 621–636. doi:10.1080/10670560600836671.

- Zhang, Linxiu; Rozelle, Scott; Liu, Chengfang; Olivia, Susan; De Brauw, Alan; Li, Qiang (November 2006). Feminization of Agriculture in China: Debunking the Myth and Measuring the Consequence of Women Participation in Agriculture (PDF) (Report). RIMISP. Retrieved 13 November 2016.