Workingmen's Party of Illinois

The Workingmen's Party of Illinois was an American political party established in the city of Chicago in December 1873. It was one of the first International Socialist political parties established in North America. Founded in the aftermath of a massive demonstration of unemployed workers, the organization ran candidates for the Common Council of Chicago and for United States Congress as well as state office in Illinois in the November 1874 election. The organization is best remembered as one of the constituent parties coming together as the Workingmen's Party of the United States in 1876 — an organization later renamed the Socialist Labor Party of America.

Workingmen's Party of Illinois | |

|---|---|

| Founded | December 1873 |

| Succeeded by | Workingmen's Party of the United States (July 1876) (Socialist Labor Party of America) |

| Ideology | International Socialism (Marxism) |

| Political position | Left-wing |

Background

Panic of 1873

The Workingmen's Party of Illinois was a radical political organization which emerged during the Panic of 1873, the greatest economic crisis in the United States between the Panic of 1837 and the Great Depression of 1929. During the fall of 1873 a severe crisis hit the American financial sector based in New York City, spurred on by the failure of financier Jay Cooke & Co. as a result of speculative overspending on construction of the Northern Pacific Railway. Cooke greatly underestimated the cost of constructing a Transcontinental railroad and was unable to sell sufficient bonds to cover construction expenses, forcing him and his banking enterprise into default.

A series of public runs on banks and bank failures followed, exacerbated by a tight money supply resulting from a recent return to the gold standard. As the economy contracted, factories shuttered and the rate of unemployment skyrocketed — with unskilled and semi-skilled labor particularly hard hit.

On December 21, 1873, some three months after the crash, the Chicago Tribune editorialized that while the wide-ranging effects of the failure of Cooke & Co. had not only "arrested and destroyed nearly every speculative scheme that was in progress, but for a time paralyzed all business," nevertheless "the panic has spent its force" and recovery had begun.[1] Certainly the railroad industry and the city's iron foundries which produced components for the industry continued to suffer, the editorialist optimistically declared, resulting in "an unusually large number of men out of employment," yet the reviving trade and commerce of Chicago had "turned the corner of the panic" and business was rapidly recovering.[1]

With another cold and bitter winter falling upon the Midwestern United States, such a starry-eyed assessment was not shared by the legion of unemployed workers of Chicago, numbering into the thousands.

Assembly of December 21, 1873

The very night that the Tribune's upbeat editorial appeared, a mass meeting of unemployed workers was convened at Turner Hall located on 12th Street in Chicago — a gathering called by a joint committee of several local social, political, and trade union organizations.[2]

Between 5,000 and 7,000 people flocked the gathering, packing the upper and lower levels of the hall to the point of suffocation, while several thousand more milled outside, unable to gain admission.[3] The meeting was regarded by contemporary observers as the largest meeting in the history of Chicago up to that time.[4] Those assembled included a goodly number of immigrants who spoke non-English tongues and the meeting was consequently featured speakers in various languages. Following the unanimous election of a chairman, the assembly was first addressed by Christian Kraus in German, followed by William Jeffers in English.[3] A.L. Hernault next took to the rostrum, speaking in French.[3] This was followed by another speaker in German and a speaker in Swedish, each making the case that the situation faced by unemployed workers was untenable, that wages of employed workers had been so reduced during the crisis to make even these insufficient, and that government and the press had turned a blind eye to the coming catastrophe.[3]

Speaking in German, Carl Blinks declared that

None felt the hard times but the workingmen... And still this was the beginning of their troubles, the times would be still worse — more terrible than anything they had yet experienced. The time had come when they should stand together shoulder to shoulder, and man by man. A capitalist in hard times...could take advantage of the bankrupt law, but a poor laborer could do nothing but take the consequences, and starve....[3]

Blinks concluded with a declaration that the following evening those concerned should assemble on the corner of Union and Washington Streets to march in a body to City Hall to see what the Chicago Common Council could do for their aid.[3] If they turned out in sufficient numbers, Blinks asserted to enthusiastic applause, the Council would be compelled to take action and the intolerable present situation would be eliminated.[3]

The stage had been set for the great march of December 22.

Organizational history

Formation of the national organization

In April 1876 a preliminary conference was gathered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to issue a formal call for a national gathering that would bring together trade union-oriented adherents of the American sections of the faltering International Workingmen's Association and other political organizations adhering to the ideas of German socialist Ferdinand Lassalle.[5] This Unity Convention was to assemble in Philadelphia on July 19 of that same year to form a new national political organization to advance the program of International Socialism.[5]

The four-day Philadelphia Unity Convention was attended by just seven voting delegates and three fraternal delegates.[6] These represented four organizations, including the Workingmen's Party of Illinois, the American sections of the International, the Social Political Workingmen's Society of Cincinnati, and the Social Democratic Workingmen's Party of North America.[7] A membership of 593 was claimed by the Workingmen's Party of Illinois at the time of the merger — larger than the Cincinnati group and very slightly smaller than the combined membership of the remaining sections of the International.[7]

The organization which resulted was to be known as the Workingmen's Party of the United States (WPUS), with Philip Van Patten of Chicago elected the first National Secretary of the organization.[7] This organization would change its name to the Socialist Labor Party of America at a convention held in December 1877, with the organization continuing in active existence for the next 125 years. Thus ended through merger the Workingmen's Party of Illinois.

Footnotes

- "The Panic in Chicago," Chicago Daily Tribune, vol. 27, no 122 (Dec. 21, 1873), pg. 8.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Volume 1: From Colonial Times to the Founding of the American Federation of Labor. New York: International Publishers, 1947; pg. 447.

- "The Unemployed: They Assemble by Thousands at the Twelfth Street Turn Hall," Chicago Daily Tribune, vol. 27, no. 123 (Dec. 22, 1873), pg. 1.

- "The Unemployed: Causes of the Great Demonstration: What the Workingmen Seek, and by What Means..." Chicago Daily Tribune, vol. 27, no. 124 (Dec. 23, 1873), pp. 1, 5.

- Frank Girard and Ben Perry, The Socialist Labor Party, 1876-1991: A Short History. Philadelphia, PA: Livra Books, 1991; pg. 3.

- Tim Davenport, "Socialist Labor Party of America (1876-1946)," Early American Marxism website, www.marxisthistory.org/

- Girard and Perry, The Socialist Labor Party, pg. 4.

Prominent members

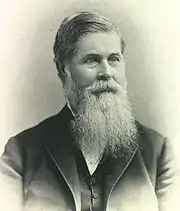

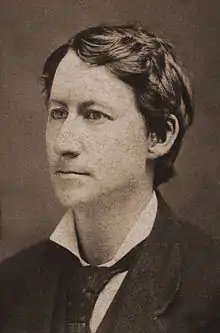

- Francis A. Hoffman, Jr.

- John McAuliffe

- Albert R. Parsons

- Philip Van Patten

Further reading

- "The Unemployed: They Assemble by Thousands at the Twelfth Street Turn Hall," Chicago Daily Tribune, vol. 27, no. 123 (Dec. 22, 1873), pg. 1.

- "The Unemployed: Causes of the Great Demonstration: What the Workingmen Seek, and by What Means..." Chicago Daily Tribune, vol. 27, no. 124 (Dec. 23, 1873), pp. 1, 5.

- "Our Communists: A Brief Sketch of the Socialist Movement: The First Organizations in Chicago," Chicago Daily Tribune, vol. 27, no. 126 (Dec. 25, 1873), pg. 1.