Yazidism

Yazidism or Sharfadin[3] (Kurdish: شهرفهدین ,Şerfedîn)[4][5] is a monotheistic ethnic religion followed by the mostly Kurmanji-speaking Yazidis and based on belief in one God who created the world and entrusted it into the care of seven Holy Beings, known as Angels.[3][6] Preeminent among these Angels is Tawûsê Melek (also written as "Melek Taus") who is the leader of the Angels and who has authority over the world.[7]

| Yazidism | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Type | Monotheistic |

| Mir | Hazim Tahsin or Naif Dawud[1] |

| Baba Sheikh | Sheikh Ali Ilyas[2] |

| Headquarters | Ain Sifni |

| Other name(s) | Şerfedîn |

Principal beliefs

Yazidism knows only one eternal God often named Xwedê.[6] According to some Yazidi hymns (known as Qewls), God has 1001 names.[8] God has created the universe[6] and the seven Angels. Among the seven Angels, Tawûsê Melek is the leader of the Angels.[7] God appointed Tawûsê Melek to take care of worldly affairs.[6]

Yazidism is a unique phenomenon, one of the most illustrative examples of ethno-religious identity, which is based on a religion exclusively specific for the Yazidis and called Sharfadin by them.[9]

Tawûsê Melek

Yazidis are called Miletê Tawûsê Melek (the nation of Melek Taus).[10]

Tawûsê Melek refused to bow before the first human, when God ordered the seven angels to do so. The command was actually a test, meant to determine which of these angels was most loyal to God by not prostrating themselves to someone other than their creator.[11]

This belief has been linked by some people to Islamic revelation on Iblis, who also refused to prostrate to Adam, despite God's express command to do so.[12] Because of this similarity to the Sufi tradition of Iblis, some followers of other monotheistic religions of the region identify the Peacock Angel with their own unredeemed evil spirit Satan,[13]:29[14] which has incited centuries of persecution of the Yazidis as "devil worshippers".[15][16] Persecution of Yazidis has continued in their home communities within the borders of modern Iraq.[17]

Yazidis, however, believe Tawûsê Melek is not a source of evil or wickedness. They consider him to be the leader of the archangels, not a fallen angel.[13][14]

Yazidis argue that the order to bow to Adam was only a test for Tawûsê Melek, since if God commands anything then it must happen. In other words, God could have made him submit to Adam, but gave Tawûsê Melek the choice as a test: God had directed him not to bow to any other being, and his refusal of the later order to bow to Adam was thus obedience to God's original command.[11]

The Yazidis of Kurdistan have been called many things, most notoriously 'devil-worshippers', a term used both by unsympathetic neighbours and fascinated Westerners. This sensational epithet is not only deeply offensive to the Yazidis themselves, but quite simply wrong.[18] Non-Yazidis have associated Melek Taus with Shaitan (Islamic/Arab name) or Satan, but Yazidis find that offensive and do not actually mention that name.[18]

The Yazidis believe in a divine triad.[19] The original god of the Yazidis is considered to be remote and inactive in relation to his creation, except to contain and bind it together within his essence.[20] His first emanation is Tawûsê Melek, who functions as the ruler of the world. The second hypostasis of this trinity is the Sheikh Adi. The third is Sultan Ezid. These are the three hypostases of the one God. The identity of these three is sometimes blurred, with Sheikh Adi considered to be a manifestation of Tawûsê Melek and vice versa. The same also applies to Sultan Ezid. A popular Yazidi story narrates the fall of Tawûsê Melek and his subsequent rejection by humanity, with the exception of the Yazidis.[19]

Seven Angels

The seven Angels are the emanations of God, which are said to have been created by God from his own light (Nûr). In this context they have, so to speak, a part of God in themselves. Another word that is used for this is Sur or Sirr (literally: mystery), which denotes a divine essence that the Angels were created from.[21] This pure divine essence called Sur or Sirr has its own personality and will and is also called Sura Xudê (the Sur of God).[22] This term refers to the essence of the Divine itself, that is, God. The Angels share this "essence" from their creator who is God. The seven Angels are sometimes referred to as the "Seven Mysteries".[21] These Angels are called Cibrayîl, Ezrayîl, Mîkayîl, Şifqayîl, Derdayîl, Ezafîl and Ezazîl.[23] Tawûsê Melek is identified with one of these Angels.

Sheikh Adi

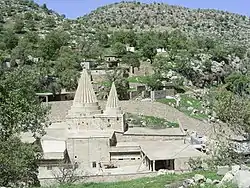

One of the important figures of Yazidism is 'Adī ibn Musafir. Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir settled in the valley of Laliş (some 58 kilometres (36 mi) northeast of Mosul) in the Yazidi mountains in the early 12th century and founded the 'Adawiyya Sufi order. He died in 1162, and his tomb at Laliş is a focal point of Yazidi pilgrimage and the principal Yazidi holy site.[24] Yazidism has many influences: Sufi influence and imagery can be seen in the religious vocabulary, especially in the terminology of the Yazidis' esoteric literature, but much of the theology is non-Islamic. Its cosmogony apparently has many points in common with those of ancient Iranian religions blended with elements of pre-Islamic ancient Mesopotamian religious traditions.[25]

Reincarnation

A belief in the reincarnation of lesser Yazidi souls also exists. Like the Ahl-e Haqq, the Yazidis use the metaphor of a change of garment to describe the process. Spiritual purification of the soul can be attained via continual reincarnation within the faith group, but it can also be halted by means of expulsion from the Yazidi community; this is the worst possible fate, since the soul's spiritual progress halts and conversion back into the faith is impossible.[26]

Creation myth

According to the Yazidi cosmogony, God created the world from a pearl (Dur), that was previously in a stage before the creation named Enzel (the eternity before creation).[27][28]

Yazidi accounts of creation differ from those of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and are closer to those of Zoroastrianism.[29]

Yazidi holy texts

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Yazidi holy books are claimed to be the Kitêba Cilwe (Book of Revelation) and the Mishefa Reş (Black Book). Scholars generally agree that the manuscripts of both books published in 1911 and 1913 were forgeries written by non-Yazidis in response to Western travellers' and scholars' interest in the Yazidi religion; however, the material in them is consistent with authentic Yazidi traditions.[30] True texts of those names may have existed, but remain obscure. The real core texts of the religion that exist today are the hymns known as qawls; they have also been orally transmitted during most of their history, but are now being collected with the assent of the community, effectively transforming Yazidism into a scriptural religion.[30] The qawls are full of cryptic allusions and usually need to be accompanied by čirōks or 'stories' that explain their context.[30]

Religious practices

Prayers

Worshipers should turn their face toward the sun.[31] Wednesday is the holy day, and the eve before is also holy.[32]

Festivals

The Yazidi New Year (Sersal) is called Çarşema Sor (Red Wednesday)[33] or Çarşema Serê Nîsanê (Wednesday at the beginning of April)[34] and it falls in Spring, on the first Wednesday on or after the 14th of April.[35]

One of the most important Yazidi festivals is Îda Êzî ("Feast of Êzî"). Which every year takes place on the first Friday on or after the 14th of December. Before this festival, the Yazidis fast for 3 days, where nothing is eaten from sunrise to sunset. The Îda Êzî festival is celebrated in honor of God and the 3 days of fasting before are also associated with the ever shorter days before the winter solstice, when the sun is less and less visible. With the Îda Êzî festival, the fasting time is ended. The festival is often celebrated with music, food, drinks and dance.[36]

Another important festival is the Tawûsgeran where Qewals and other religious dignitaries visit Yazidi villages, bringing the sinjaq, sacred images of a peacock symbolizing Tawûsê Melek. These are venerated, fees are collected from the pious, sermons are preached and holy water and berat (small stones from Lalish) distributed.[37][38]

The greatest festival of the year is the Cemaiya ("Feast of the Assembly"), which includes an annual pilgrimage to the tomb of Sheikh Adi (Şêx Adî) in Lalish, northern Iraq. The festival is celebrated from 6 October to 13 October,[39] in honor of the Sheikh Adi. It is an important time for cohesion.[40]

If possible, Yazidis make at least one pilgrimage to Lalish during their lifetime, and those living in the region try to attend at least once a year for the Feast of the Assembly in autumn.[41]

Purity and taboos

Many Yazidis consider pork to be prohibited. However, many Yazidis living in Germany began to view this taboo as a foreign belief from Judaism or Islam and not part of Yazidism, and therefore abandoned this rule.[43]

Too much contact with non-Yazidis is also considered polluting. In the past, Yazidis avoided military service which would have led them to live among Muslims and were forbidden to share such items as cups or razors with outsiders. A resemblance to the external ear may lie behind the taboo against eating head lettuce, whose name koas resembles Yazidi pronunciations of koasasa. Additionally, lettuce grown near Mosul is thought by some Yazidis to be fertilised with human waste, which may contribute to the idea that it is unsuitable for consumption. However, in a BBC interview in April 2010, a senior Yazidi authority stated that ordinary Yazidis may eat what they want, but holy men refrain from certain vegetables (including cabbage) because "they cause gases".[44]

A minority of Yazidis in Armenia and Georgia converted to Christianity,[45] but they are not accepted by the other Yazidis as Yazidis.[46]

Customs

Children are baptised at birth and circumcision is not required, but is practised by some due to regional customs.[47] The Yazidi baptism is called Mor kirin (literally: "to seal"). Traditionally, Yazidi children are baptised at birth with water from the Kaniya Sipî ("White Spring") at Lalish.[48]

Religious organisation

The Yazidis are strictly endogamous;[49][50] members of the three Yazidi castes, the murids, sheikhs, and pirs, marry only within their group.[14]

There are several religious duties and that are performed by several dignitaries.

References

- "Yezidis divided on spiritual leader's successor elect rival Mir".

- "The Yazidis are still struggling to survive". The Economist. 2020-12-10. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (2014-09-03). The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. Routledge. ISBN 9781317544296.

- Rodziewicz, Artur (2018). "Chapter 7: The Nation of the Sur: The Yezidi Identity Between Modern and Ancient Myth". In Bocheńska, Joanna (ed.). Rediscovering Kurdistan's Cultures and Identities: The Call of the Cricket. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 272. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93088-6_7. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6.

- "مهزارگههێ شهرفهدین هێشتا ژ ئالیێ هێزێن پێشمهرگهی ڤه دهێته پاراستن" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014-12-23). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857720610.

- Maisel, Sebastian (2016-12-24). Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739177754.

- Kartal, Celalettin (2016-06-22). Deutsche Yeziden: Geschichte, Gegenwart, Prognosen (in German). Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 9783828864887.

- Arakelova, Victoria. "Ethno-Religious Communities Identity markers". Yerevan State University. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (2014-09-03). The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-54428-9.

- Khalaf, Farida; Hoffmann, Andrea C. (2016-07-07). The Girl Who Escaped ISIS: Farida's Story. Random House. ISBN 9781473524163.

- Asatrian and Arakelova 2014, 26–29

- van Bruinessen, Martin (1992). "Chapter 2: Kurdish society, ethnicity, nationalism and refugee problems". In Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (eds.). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 26–52. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6. OCLC 919303390.

- Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. London: I.B. Tauris & Company. ISBN 978-1-784-53216-1. OCLC 888467694.

- Li, Shirley (8 August 2014). "A Very Brief History of the Yazidi and What They're Up Against in Iraq". The Atlantic.

- Jalabi, Raya (11 August 2014). "Who are the Yazidis and why is Isis hunting them?". The Guardian.

- Thomas, Sean (19 August 2007). "The Devil worshippers of Iraq". The Daily Telegraph.

- "The Evolution of Yezidi Religion - From Spoken Word to Written Scripture" (PDF). Openaccess.leidenuniv.nl.

- Garnik S. Asatrian, Victoria Arakelova (2014). The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. ISBN 978-1317544289. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Izady, Mehrdad (2015). The Kurds: A Concise History And Fact Book. ISBN 9781135844905. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Spät, Eszter (2009). "Late Antique Motifs in Yezidi Oral Tradition" (PDF). Central European University. p. 71.

- Rodziewicz, Artur (2018). "Chapter 7: The Nation of the Sur: The Yezidi Identity Between Modern and Ancient Myth". In Bocheńska, Joanna (ed.). Rediscovering Kurdistan's Cultures and Identities: The Call of the Cricket. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93088-6_7. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6.

- Авдоев, Теймураз. "Т. Авдоев Историко-теософский аспект езидизма": 314. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Late Antique Motifs in Yezidi Oral Tradition by Eszter Spät. Ch. 9 "The Origin Myth of the Yezidis" section "The Myth of Shehid Bin Jer" (p. 347)

- Eckardt, Frank; Eade, John (1 January 2011). The Ethnically Diverse City. BWV Verlag. p. 73. ISBN 978-3-8305-1641-5.

- Darke, Diana; Leutheuser, Robert (8 August 2014). "Who, What, Why: Who are the Yazidis?". Magazine Monitor, BBC News.

- Franz, Erhard (2004). "Yeziden - Eine alte Religionsgemeinschaft zwischen Tradition und Moderne" (PDF). Deutsches Orient-Institut.

- Omarkhali, Khanna. "(with Rezania, K.). Some reflections on the concepts of time in Yezidism". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Richard Foltz Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present Oneworld Publications, 01.11.2013 ISBN 9781780743097 p. 221

- "Encyclopaedia Iranica: Yazidis". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- Maisel, Sebastian (2016-12-24). Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739177754.

- Bogdan, Henrik; Starr, Martin P. (2012-09-20). Aleister Crowley and Western Esotericism. OUP USA. ISBN 9780199863099.

- Rodziewicz, Artur. "And the Pearl Became an Egg: The Yezidi Red Wednesday and Its Cosmogonic Background". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Авдоев, Теймураз (2017-09-05). Историко-теософский аспект езидизма (in Russian). Litres. ISBN 9785040433988.

- "Das êzîdîsche Neujahr" (PDF).

- Urban, Elke (2019-07-24). Transkulturelle Pflege am Lebensende: Umgang mit Sterbenden und Verstorbenen unterschiedlicher Religionen und Kulturen (in German). Kohlhammer Verlag. ISBN 9783170359383.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (2009). Yezidism in Europe: Different Generations Speak about Their Religion. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447060608.

- Maisel, Sebastian (2016-12-24). Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building among a Double Minority. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739177754.

- Guest (2012-11-12). Survival Among The Kurds. Routledge. ISBN 9781136157363.

- Yousefi, Hamid Reza; Seubert, Harald (2014-07-22). Ethik im Weltkontext: Geschichten - Erscheinungsformen - Neuere Konzepte (in German). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 9783658048976.

- Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014-12-23). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857720610.

- Lair, Patrick (19 January 2008). "Conversation with a Yazidi Kurd". eKurd Daily. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- Halil Savucu: Yeziden in Deutschland: Eine Religionsgemeinschaft zwischen Tradition, Integration und Assimilation Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag, Marburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-828-86547-1, Section 16 (German)

- "Richness of Iraq's minority religions revealed", BBC. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "Population (urban, rural) by Ethnicity, Sex and Religious Belief" (PDF). Statistics of Armenia. Statistics of Armenia. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Aghayeva, Elene Shengelia, Rana (2018-09-06). "Georgia's Yazidis: Religion as Identity - Religious Beliefs". chai-khana.org. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- Parry, O. H. (Oswald Hutton) (1895). "Six months in a Syrian monastery; being the record of a visit to the head quarters of the Syrian church in Mesopotamia, with some account of the Yazidis or devil worshippers of Mosul and El Jilwah, their sacred book". London : H. Cox.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (2009). Yezidism in Europe: Different Generations Speak about Their Religion. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-06060-8.

- Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014-12-23). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857720610.

- Gidda, Mirren. "Everything You Need to Know About the Yazidis". TIME.com. Retrieved 2016-02-07.