Yonahlossee salamander

The Yonahlossee salamander (Plethodon yonahlossee) is a particularly large woodland salamander from the southern Appalachian Mountains in the United States. The species is a member of the family Plethodontidae, which is characterized by being lungless and reproductive direct development. P. yonahlossee was first described in 1917 by E.R Dunn on a collection site on Grandfather Mountain in North Carolina.[3][4] The common and specific name is of Native American origin, meaning “trail of the bear”. It is derived from Yonahlossee Road northeast of Linville, where the specimen was first described.[5]

| Yonahlossee salamander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Plethodontidae |

| Subfamily: | Plethodontinae |

| Genus: | Plethodon |

| Species: | P. yonahlossee |

| Binomial name | |

| Plethodon yonahlossee | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

Plethodon longicrus Adler & Dennis, 1962 | |

Description

P. yonahlossee is a large Southern Appalachian woodland salamander typically differentiated by its large size and its distinctive rust-colored dorsum. As with all other members of the genus, Plethodon yonahlossee is lungless and a direct developer, meaning no larval stage is seen; instead, the young hatch into miniature adults, and fully metamorphosed adult individuals are characterized by a nasolabial groove that aids in chemoreception.[5] The yonahlossee's back has a black base color and is covered by reddish-brown to red blotches depending on age. Typically, juveniles are more spotted, while in older individuals, the reddish blotches come together to form a wide band spanning the length of their backs. The sides of their bodies are covered with grey to white blotching, and the dorsal part of their heads is all black. The belly and throat are both pigmented, but sometimes have a similar blotched pattern as the back.[6] P. yonahlossee is the largest member of the family Plethodontidae in North America. Females are significantly larger than males. The typical adult length is between 11 and 22 cm. Typically, the yonahlossee has 15 or 16 costal grooves.[5]

Distribution

P. yonahlossee can be found in the southern Blue Ridge Mountains of northern Tennessee, western North Carolina, and small portions of southwest Virginia. Specifically, they have been located in Avery, Yancey, and Rutherford Counties in North Carolina; Rocky Fork State Park & Limestone Cove in Unicoi County, Tennessee, and Whitetop Mountain, Virginia. They are found in a variety of upland wooded habitats. They tend to be located in deciduous forests at elevations between 437 and 1,737 m, but tend to be more altitudinally restricted compared to other members of Plethodontidae.[5] They are also commonly found in damp, shaded areas around wooded hillsides and ravines, where rock slides are covered with mosses and ferns; areas with old windfalls; and grassy areas near woodlands. A unique population only found in Rutherford County, North Carolina, occurs near Bat Cave and is often found in rock crevices, but is sometimes recognized as a separate species characterized by different coloration and limb morphology, P. longicrus. These Bat Cave variants may have red of the dorsum prominent, patchy, or even lacking, and their sides are dark with light spots. The coloration of the Bat Cave variant is much darker than the common P. yonahlossee, and some scientists still consider them to be a separate species. Furthermore, the variant does not reach sexual maturity like P. yonahlossee, but matures according to size. Males must reach greater than 65 mm and females must be greater than 61 mm before being considered mature.[7]

During the day, it takes cover under rotting logs, rocks, or in burrows on the forest floor which are under logs, although it is argued whether or not they create these burrows or just reopen partly eradicated passages.[5] They prefer areas of old windfalls that have shed most of their bark and logs greater than 25 cm in diameter with no more than 5 to 15 cm of the log below the surface and a thick layer of leaf litter at the interface between the log and the ground. They can also be found active on humid or rainy nights, even crossing roads in suitable habitat.[8]

Behavior and ecology

Little is known about the reproductive habits of this species. Reproduction does take place terrestrially and eggs are deposited in underground cavities where, like other members of the genus, the female may guard the eggs until they hatch.[9] Spermatogenesis most likely occurs after the emergence from hibernation. Courtship is assumed to occur in early August, as this is the time pairs of salamanders have been found under a single cover object and males have noticeably enlarged mental glands. Females then lay their eggs in late August or early September. Clutch size is dependent on the size of the female, but typically ranges from 19 to 27.[5]

Sexual maturity is thought to be around three years of age. Also, a definitive feature of maturity is the length of the mental glands which in males is about 56 mm, whereas in females it is more like 60 to 66 mm, depending again on the size of the female.[5]

Both adults and juveniles emerge at night to forage. Juveniles have been found to be most active one hour after sunset, while adults peak one to two hours later. Each stage is carnivorous and eats small insects and invertebrates, including mites, spiders, millipedes, centipedes, and earthworms.[6]

Predators likely include snakes, birds, and small mammals. To escape predation, P. yonahlossee produces secretions from its tail that are noxious to birds and other mammals. Also, after initial contact, they become immobile, making them harder to detect, which may increase survival from visual predators.[5]

In laboratory settings, Yonahlossee salamanders demonstrated aggressive defense of their territories. Like most species in the genus, they exhibit vertical underground migration and move underground during cold winter.[5]

Conservation

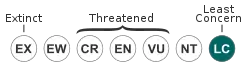

As of 2014, P. yonahlossee is listed as a least concern species.[1] Criteria for this listing include occurrence in an area of extensive, suitable habitat which appears to not be under any substantial threat, an assumed large population, and a slow rate of decline.[10]

P. yonahlossee among other terrestrial salamanders has been reported to have no change in abundance in single or several locales over many years. Concurrently, others are viewing the same species over the entire range and are reporting that many populations have been lost to habitat destruction, which includes urban sprawl and increased forestry practices.[11] Clearly, a possibility exists for one species to be locally abundant with stable populations, yet still be declining throughout the range. Salamander habitat loss is mainly due to outright destruction, fragmentation, forestry practice, and pollution.[12]

References

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2014). "Plethodon yonahlossee". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T59364A56261046. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T59364A56261046.en.

- Dunn, Emmett R. (1917). "Reptile and amphibian collections from the North Carolina mountains, with especial reference to salamanders". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 37 (23): 598–603. hdl:2246/1755; Pl. 57, Figs. 1–3.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2017). "Plethodon yonahlossee Dunn, 1917". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Behler, John L. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979. Print.

- Lannoo, Michael J. Amphibian Declines: the Conservation Status of United States Species. Berkeley: University of California, 2005. 856-857. Print.

- Hammerson, G. 2004. Plethodon yonahlossee. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. Downloaded on 02 June 2013.

- Bartlett, Richard D., and Patricia Pope Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America (north of Mexico). Gainesville: University of Florida, 2006. 218-219. Print.

- Pough, F. Harvey. Herpetology. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2004. Print.

- Martof, Bernard S. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1980. 99. Print.

- 2001 Categories & Criteria (version 3.1). IUCN.

- Petranka, James W. (1994). "Response to Impact of timber harvesting on salamanders". Conservation Biology. 8 (1): 302–303. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1994.08010302.x. JSTOR 2386751.

- Semlitsch, Raymond D. Amphibian Conservation. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 2003. 37-52. Print.