Yusufzai

The Yusufzai or Yousafzai (Pashto: یوسفزی, pronounced [jusəpˈzay]1), also referred to as the Esapzai (ايسپزی, pronounced [iːsəpˈzay]), are one of the largest tribes of the ethnic Pashtun people.

ايسپزی | |

|---|---|

_(14596635677).jpg.webp) Yusufzai Pashtuns in a Hill Tract (1895) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Pakistan, Afghanistan, India[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Pashto | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Pashtun tribes |

They are natively based in northern and eastern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan and parts of eastern Afghanistan. Outside of these countries, they can also be found in large numbers in Rohilkhand, Uttar Pradesh, India.[1]

Their name may originate from the names of the Aspasioi and the Aśvakan, who were the ancient inhabitants of Kunar, Swat, and adjoining valleys in the Hindu Kush.[2] Malala Yousafzai, the youngest Nobel Prize laureate, belongs to the Yusufzai tribe.[3]

Most of the Yusufzai speak a northern variety of Pashto; the Yusufzai dialect is considered prestigious in Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.[4]

Etymology

In Pashto phonology, as /f/ is found only in loanwords and tends to be replaced by /p/,[5] the name is usually pronounced as Yūsəpzay or Īsəpzay. The name literally means "descendant of Yusuf" in Pashto; Yūsuf (يوسف) is an Arabic and Aramaic masculine given name meaning "(God) shall add."

According to some scholars, including philologist J.W. McCrindle, the name Yūsəpzay or Īsəpzay is derived from the tribal names of Aspasioi and Assakenoi – the ancient inhabitants of the Kunar Valley and the Swat Valley who offered resistance when Alexander invaded their land in 327–326 BCE. According to historian R.C. Majumdar, the Assakenoi were either allied to or a branch of the larger Aspasioi, and both of these ancient tribal names were probably derived from the word Aśvaka, which literally means "horsemen", "horse breeders", or "cavalrymen" (from aśva or aspa, the Sanskrit and Avestan words for "horse").[6]

McCrindle noted: "The name of the Aśvaka indicates that their country was renowned in primitive times, as it is at the present day, for its superior breed of horses. The fact that the Greeks translated their name into "Hippasioi" (from ἵππος, a horse) shows that they must have been aware of its etymological signification."[2]

The name of the Aśvakan or Assakan has also been preserved in the name Afghān, which is a historical ethnonym for all Pashtuns.[7][8][9][10][11]

Mythical genealogy

According to a popular mythical genealogy, recorded by 17th-century Mughal courtier Nimat Allah al-Harawi in his book Tārīkh-i Khān Jahānī wa Makhzan-i Afghānī, the Yusufzai tribe descended from their eponymous ancestor Yūsuf, who was son of Mand, who was son of Khashay (or Khakhay), who was son of Kand, who was son of Kharshbūn, who was son of Saṛban (progenitor of the Sarbani tribal confederacy), who was son of Qais Abdur Rashid (progenitor of all Pashtuns). Qais Abdur Rashid was a descendant of Afghana, who was described as a grandson of the Israelite king Saul and commander-in-chief of the army of prophet Solomon. Qais was claimed to be a contemporary of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a kinsman of Arab commander Khalid ibn al-Walid. When Khalid ibn al-Walid summoned Qais from Ghor to Medina, Qais accepted Islam and the prophet renamed him Abdur Rashīd (meaning "Servant of the Guide to the Right Path" or "Servant of God" in Arabic). Abdur Rashid returned to Ghor and introduced Islam there. The book stated that Yūsuf's grandfather (and Mand's father), Khashay, also had two other sons, Muk and Tarkalāṇī, who were the progenitors of the Gigyani and Tarkani tribes, respectively. Yūsuf had one brother, Umar, who was the progenitor of the Mandanr tribe, which is closely related to Yusufzais.

The 1595 Mughal account Ain-i-Akbari also mentioned the tradition of Israelite descent among Pashtuns, which shows that the tradition was already popular among 16th-century Pashtuns.[12]

History

Peace treaty with Babur

In the early modern period, the Yusufzai tribe of Pashtuns was first explicitly mentioned in Baburnama by Babur, a Timurid ruler from Fergana (in present-day Uzbekistan) who captured Kabul in 1504.[13] On 21 January 1519, two weeks after his Bajaur massacre, Babur wrote: "On Friday we marched for Sawad (Swat), with the intention of attacking the Yusufzai Afghans, and dismounted in between the water of Panjkora and the united waters of Chandāwal (Jandul) and Bajaur. Shah Mansur Yusufzai had brought a few well-flavoured and quite intoxicating confections."[14]

As part of a peace treaty with Yusufzai Pashtuns, Babur married Bibi Mubarika, daughter of Yusufzai chief Shah Mansur, on 30 January 1519.[15] Mubarika played an important role in the establishment of friendly relations of Yusufzai Pashtun chiefs with Babur, who later founded the Mughal Empire after defeating Pashtun Sultan Ibrahim Lodi at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526.[16] One of Mubarika's brothers, Mir Jamal Yusufzai, accompanied Babur to India in 1525 and later held high posts under Mughal emperors Humayun and Akbar.[17]

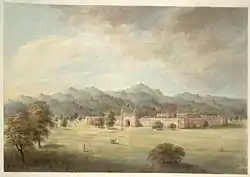

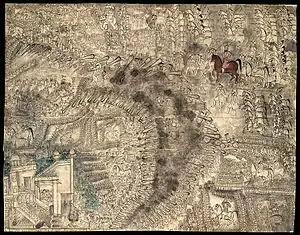

Skirmishes with Mughal forces

During the 1580s, many Yusufzais and Mandanrs rebelled against the Mughals and joined the Roshani movement of Pir Roshan.[18] In late 1585, Mughal Emperor Akbar sent military forces under Zain Khan Koka and Birbal to crush the rebellion. In February 1586, about 8,000 Mughal soldiers, including Birbal, were killed near the Karakar Pass between Swat and Buner by the Yusufzai lashkar led by Kalu Khan. This was the greatest disaster faced by the Mughal Army during Akbar's reign.[19]

In 1630, under the leadership of Pir Roshan's great-grandson, Abdul Qadir, thousands of Pashtuns from the Yusufzai, Mandanrs, Kheshgi, Mohmand, Afridi, Bangash, and other tribes launched an attack on the Mughal Army in Peshawar.[20] In 1667, the Yusufzai again revolted against the Mughals, with one of their chiefs in Swat proclaiming himself the king. Muhammad Amin Khan brought a 9,000 strong Mughal Army from Delhi to suppress the revolt.[21] Although the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb was able to conquer the southern Yusufzai plains within the northern Kabul valley, he failed to wrest Swat and the adjoining valleys from the control of the Yusufzai.[22]

Durrani period

Ahmad Shah Durrani (1747–1772), the founder of the Afghan Durrani Empire, categorized all Pashtun tribes into four ulūs (tribal confederacies) for administrative purposes: Durrani, Ghilji, Sur, and Bar Durrani ("Upper Durranis"). The Yusufzai were included in the Bar Durrani confederacy along with other eastern Pashtun tribes, including the Mohmand, Afridi, Bangash, and Khattak.[12] The Bar Durrani were also known as the Rohilla, and comprised the bulk of those Pashtuns who settled in Rohilkhand, India.[22]

Najib ad-Dawlah, who belonged to the Yusufzai tribe, was a prominent Rohilla chief. In the 1740s, he founded the city of Najibabad in Rohilkhand. In 1757, he supported Ahmad Shah Durrani in his attack on Delhi. After his victory, Ahmad Shah Durrani re-installed the Mughal emperor Alamgir II on the Delhi throne as the titular Mughal head, but gave the actual control of Delhi to Najib ad-Daula. From 1757 to 1770, Najib ad-Daula served as the governor of Saharanpur, also ruling over Dehradun. In 1761, he took part in the Third Battle of Panipat and provided thousands of Rohilla troops and many guns to Ahmad Shah Durrani to defeat the Marathas.[23] He also convinced Shuja-ud-Daula, the Nawab of Awadh, to join the Durrani forces. Before his departure from Delhi, Ahmad Shah Durrani appointed Najib ad-Dawlah as mir bakshi (paymaster-general) of the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II.[24] After his death in 1770, Najib ad-Dawlah was succeeded by his son, Zabita Khan, who was defeated in 1772 by the Marathas, forcing him to flee from Rohilkhand. However, the descendants of Najib ad-Dawlah continued to rule Najibabad area until they were defeated by the British at Nagina on 21 April 1858 during the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[25]

Today, many Yusufzais are settled in India, most notably in Rohilkhand region, as well as in Farrukhabad, which was founded in 1714 by Pashtun Nawab Muhammad Khan Bangash.[1][26]

States of Swat and Dir

In 1849, Yusufzais established the state of Swat under the leadership of Saidu Baba, who appointed Sayyid Akbar Shah, a descendant of Pir Baba, as the first emir. After Akbar Shah's death in 1857, Saidu Baba assumed control of the state himself.[27] In Dir, descendants of 17th-century Akhund Ilyas Yusufzai, the founder of the city of Dir, laid the foundation of the state of Dir. In 1897, the British Raj annexed Dir and granted the title of the "Nawab of Dir" to Sharif Khan Akhundkhel, the ruler of Dir (1886–1904).[28][29] In 1926, the British Raj granted the title of the "Wali of Swat" to Miangul Abdul Wadud, the ruler of Swat (1918–1949).[30]

The princely states of Swat and Dir existed until 1969, after which they were merged into West Pakistan, and then in 1970 into the North-West Frontier Province (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) of Pakistan.[30] Their area is part of the present-day Buner, Lower Dir, Upper Dir, Malakand, Shangla, and Swat districts.

Pashto dialect

Yusufzai Pashto, which is a variety of Northern Pashto, is the prestige variety of Pashto in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Some of its consonants differ from the other dialects:[4]

| Dialects[31] | ښ | ږ | څ | ځ | ژ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yusufzai Pashto | [x] | [ɡ] | [s, t͡s] | [z] | [d͡ʒ] |

| Ghilji Pashto | [ç] | [ʝ] | [t͡s] | [z] | [ʒ, z] |

| Durrani Pashto | [ʂ] | [ʐ] | [t͡s] | [d͡z] | [ʒ] |

Society

The Yusufzai Pashtun aristocracy was historically divided into several communities based on patrilineal segmentary groups:[22]

- Khān

The khān referred to the Yusufzai landowners. In the 16th century, saint Sheikh Mali, a prominent Yusufzai dignitary, distributed the Yusufzai land among the major Yusufzai tribal clans (khēl). However, to avoid inequalities, he ordered that the lands should not become permanent property of the clans, but rather they should be realloted within the patrilineal clans periodically after every ten years or so. In this system (wēsh), each landowning khān would own shares (brakha) representing his proportion of the total area distributed. Through a regular rotation of ownership, the Yusufzai landowners would migrate for up to 30 miles for their new share after each cycle, although the tenants cultivating the land would stay on.

The wēsh system operated among the Yusufzai of Swat region until at least 1920s.[32]

- Hamsāya

The hamsāya or "shade sharers" were the clients or dependents from other (non-Yusufzai) Pashtun tribes who became attached to the Yusufzai tribe over the years.

- Faqīr

The faqīr or "poor" were the non-Pashtun landless peasants who were assigned to the Yusufzai landowners. As dependent peasants, the faqīr used to pay rent for the land they cultivated.

In the 19th century, the distinction between hamsāya as a "dependent Pashtun tribe" and faqīr as "non-Pashtun landless peasants" became blurred. Both terms were then interchangeably used to simply refer to landless dependents or clients.

- Mlātəṛ

The mlātəṛ or "supporters" provided services to their patrons as artisans (kasabgar), musicians (ḍəm), herders, or commercial agents, mostly in return for a payment in grain or rice.

- Ghulām

The ghulām or "slaves" were more closely attached to their patron and his family and frequently entrusted with a variety of functions within their master's household. Although the ghulām were less free as compared to the hamsāya or the faqīr, they generally enjoyed a higher status in the society.

Subtribes

See also

Notes

- ^1 In Pashto, "Yusufzai" (یوسفزی, [jusəpˈzay]) is the masculine singular form of the word. Its feminine singular is "Yusufzey" (یوسفزۍ, [jusəpˈzəy]), while its plural is "Yusufzi" (یوسفزي, [jusəpˈzi]).

References

- Haleem, Safia (24 July 2007). "Study of the Pathan Communities in Four States of India". Khyber Gateway. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

Farrukhabad has a mixed population of Pathans dominated by the Bangash and Yousafzais.

- John Watson McCrindle (1896). The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great: As Described by Arrian, Q. Curtius, Diodoros, Plutarch and Justin. University of Michigan: A. Constable. pp. 333–334.

- "Following in Benazir's footsteps, Malala aspires to become PM of Pakistan". The Express Tribune. 10 December 2014. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Coyle, Dennis Walter (August 2014). "Placing Wardak among Pashto varieties" (PDF). University of North Dakota:UND. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Tegey, Habibullah; Robson, Barbara (1996). A Reference Grammar of Pashto (PDF). Washington: Center for Applied Linguistics. p. 15.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1977) [1952]. Ancient India (Reprinted ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. p. 99. ISBN 978-8-12080-436-4.

- "The name Afghan has evidently been derived from Asvakan, the Assakenoi of Arrian... " (Megasthenes and Arrian, p 180. See also: Alexander's Invasion of India, p 38; J.W. McCrindle).

- "Even the name Afghan is Aryan being derived from Asvakayana, an important clan of the Asvakas or horsemen who must have derived this title from their handling of celebrated breeds of horses" (See: Imprints of Indian Thought and Culture abroad, p 124, Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan).

- cf: "Their name (Afghan) means "cavalier" being derived from the Sanskrit, Asva, or Asvaka, a horse, and shows that their country must have been noted in ancient times, as it is at the present day, for its superior breed of horses. Asvaka was an important tribe settled north to Kabul river, which offered a gallant resistance but ineffectual resistance to the arms of Alexander "(Ref: Scottish Geographical Magazine, 1999, p 275, Royal Scottish Geographical Society).

- "Afghans are Assakani of the Greeks; this word being the Sanskrit Ashvaka meaning 'horsemen' " (Ref: Sva, 1915, p 113, Christopher Molesworth Birdwood).

- Cf: "The name represents Sanskrit Asvaka in the sense of a cavalier, and this reappears scarcely modified in the Assakani or Assakeni of the historians of the expedition of Alexander" (Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases, and of kindred terms, etymological..by Henry Yule, AD Burnell).

- The Pearl of Pearls: The Abdālī-Durrānī Confederacy and Its Transformation under Aḥmad Shāh, Durr-i Durrān by Sajjad Nejatie. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/80750.

- Samrin, Farah (2006). "Yusufzais in Mughal History". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 67: 292–300. JSTOR 44147949.

- Beveridge, Annette Susannah (7 January 2014). The Bābur-nāma in English, Memoirs of Bābur. Project Gutenberg.

- Shyam, Radhey (1978). Babur. Janaki Prakashan. p. 263.

- Aftab, Tahera; edited; Hiro, introduced by Dilip (2008). Inscribing South Asian Muslim women : an annotated bibliography & research guide ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Leiden: Brill. p. 46. ISBN 9789004158498.

- Mukherjee, Soma (2001). Royal Mughal Ladies and Their Contributions. Gyan Books. p. 118. ISBN 978-8-121-20760-7.

- "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 19– Imperial Gazetteer of India". Digital South Asia Library. p. 152. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780521566032.

- Misdaq, Nabi (2006). Afghanistan: Political Frailty and External Interference. Routledge. ISBN 1135990174.

- Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. ISBN 9780521566032.

- Gommans, Jos J.L. (1995). The Rise of the Indo-Afghan Empire: C. 1710-1780. BRILL. p. 219. ISBN 9004101098.

- Najibabad Tehsil & Town The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909, v. 18, p. 334.

- History of Modern India, 1707 A. D. to 2000 A. D

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 928.

- Haleem, Safia (24 July 2007). "Study of the Pathan Communities in Four States of India". Khyber Gateway. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Haroon, Sana (2011). Frontier of Faith: Islam, in the Indo-Afghan Borderland. Hurst Publishers. p. 40. ISBN 978-1849041836. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Who's Who in the Dir, Swat and Chitral Agency – Corrected up to 1st September 1933 (PDF). New Delhi: The Manager Government of India Press. 1933. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- Dir at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Claus, Peter J.; Diamond, Sarah; Ann Mills, Margaret (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-41593-919-5.

- Hallberg, Daniel G. 1992. Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan, 4.

- Noelle, Christine (2012). State and Tribe in Nineteenth-Century Afghanistan: The Reign of Amir Dost Muhammad Khan (1826-1863). Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-1136603174.