Zebra

Zebras[lower-alpha 1] (subgenus Hippotigris) are African equines with distinctive black-and-white striped coats. There are three extant species: the Grévy's zebra (Equus grevyi), plains zebra (E. quagga), and the mountain zebra (E. zebra). Zebras share the genus Equus with horses and asses, the three groups being the only living members of the family Equidae. Zebra stripes come in different patterns, unique to each individual. Several theories have been proposed for the function of these stripes, with most evidence supporting them as a form of protection from biting flies. Zebras inhabit eastern and southern Africa and can be found in a variety of habitats such as savannahs, grasslands, woodlands, shrublands, and mountainous areas.

| Zebra Temporal range: Pliocene to recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| A herd of plains zebras (Equus quagga) in the Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Subgenus: | Hippotigris C. H. Smith, 1841 |

| Species | |

|

†E. capensis | |

| |

| Modern range of the three living zebra species | |

Zebras are primarily grazers and can subsist on lower-quality vegetation. They are preyed on mainly by lions and typically flee when threatened but also bite and kick. Zebra species differ in social behaviour, with plains and mountain zebra living in stable harems consisting of an adult male or stallion, several adult females or mares, and their young or foals; while Grévy's zebra live alone or in loosely associated herds. In harem-holding species, adult females mate only with their harem stallion, while male Grévy's zebras establish territories which attract females and the species is promiscuous. Zebras communicate with various vocalisations, body postures and facial expressions. Social grooming strengthens social bonds in plains and mountain zebras.

Zebras' dazzling stripes make them among the most recognisable mammals. They have been featured in art and stories in Africa and beyond. Historically, they have been highly sought after by exotic animal collectors, but unlike horses and donkeys, zebras have never been truly domesticated. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the Grévy's zebra as endangered, the mountain zebra as vulnerable and the plains zebra as near-threatened. The quagga, a type of plains zebra, was driven to extinction in the 19th century. Nevertheless, zebras can be found in numerous protected areas.

Etymology

The English name "zebra" dates back to c. 1600, deriving from Italian, Spanish or Portuguese.[1][2] Its origins may lie in the Latin equiferus meaning "wild horse"; from equus ("horse") and ferus ("wild, untamed"). Equiferus appears to have entered into Portuguese as ezebro or zebro, which was originally a name for a mysterious (possibly feral) equine in the wilds of the Iberian Peninsula during the Middle Ages.[3] In ancient times, the zebra was called hippotigris ("horse tiger") by the Greeks and Romans.[3][4]

The word "zebra" was traditionally pronounced with a long initial vowel, but over the course of the 20th century the pronunciation with the short initial vowel became the norm in the UK and the Commonwealth.[5] The pronunciation with a long initial vowel remains standard in US English.[6] A group of zebras is referred to as a herd, dazzle, or zeal.[7]

Taxonomy and evolution

Zebras are classified in the genus Equus (known as equines) along with horses and asses. These three groups are the only living members of the family Equidae.[8] The plains zebra and mountain zebra were traditionally placed in the subgenus Hippotigris (C. H. Smith, 1841) in contrast to the Grévy's zebra which was considered the sole species of subgenus Dolichohippus (Heller, 1912).[9][10][11] Groves and Bell (2004) placed all three species in the subgenus Hippotigris.[12] A 2013 phylogenetic study found that the plains zebra is more closely related to Grévy's zebras than mountain zebras.[13] The extinct quagga was originally classified as a distinct species.[14] Later genetic studies have placed it as the same species as the plains zebra, either a subspecies or just the southernmost population.[15][16] Molecular evidence supports zebras as a monophyletic lineage.[13][17][18]

Equus originated in North America and direct paleogenomic sequencing of a 700,000-year-old middle Pleistocene horse metapodial bone from Canada implies a date of 4.07 million years ago (mya) for the most recent common ancestor of the equines within the range of 4.0 to 4.5 mya.[19] Horses split from asses and zebras around 4 mya, and equines entered Eurasia around 3 mya. Zebras and asses diverged from each other close to 2.8 mya and zebra ancestors entered Africa around 2.3 mya. The mountain zebra diverged from the other species around 1.75 mya and the plains and Grévy's zebra split around 1.5 mya.[13][20][21]

The cladogram of Equus below is based on Vilstrup and colleagues (2013):[13]

| Equus |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extant species

| Name | Description | Distribution | Subspecies | Chromosomes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grévy's zebra (Equus grevyi) | Body length of 250–300 cm (8.2–9.8 ft) with 38–75 cm (15–30 in) tail, 125–160 cm (4.10–5.25 ft) shoulder height and weighs 352–450 kg (776–992 lb);[22] Mule-like appearance with narrow skull, robust neck and conical ears; narrow striping pattern with concentric rump stripes, white belly and tail base and white margin around the muzzle[8][23][24] | Eastern Africa including the Horn;[23] arid and semiarid grasslands and shrublands[25] | Monotypic[23] | 46[25] |  |

| Plains zebra (Equus quagga) | Body length of 217–246 cm (7.12–8.07 ft) with 47–56 cm (19–22 in) tail, 110–145 cm (3.61–4.76 ft) shoulder height and weighs 175–385 kg (386–849 lb);[22] Dumpy bodied with relatively short legs and a skull with a convex forehead and a somewhat concave nose profile;[8][26] broad stripes, horizontal on the rump, with northern populations having more extensive striping while populations further south have whiter legs and bellies as well as more brown "shadow" stripes in-between black stripes[8][27][28][29] | Eastern and southern Africa; savannahs, grasslands and open woodlands[30] | 6[12] or monotypic[16] | 44[27] |  |

| Mountain zebra (Equus zebra) | Body length of 210–260 cm (6.9–8.5 ft) with 40–55 cm (16–22 in) tail, 116–146 cm (3.81–4.79 ft) shoulder height and weighs 204–430 kg (450–948 lb);[22] eye sockets more rounded and positioned farther back, a squarer nuchal crest, dewlap present under neck and compact hooves; stripes intermediate in width between the other species, with gridiron and horizontal stripes on the rump, while the belly is white and the muzzle is lined with chestnut or orange[31][8][32][25] | Southwestern Africa; mountains, rocky uplands and Karoo shrubland[30][31] | 2[31] | 32[25] |  |

_(14586585048).jpg.webp)

Fossil record

In addition to the three extant species, some fossil zebras have also been identified. Equus koobiforensis is an early zebra or equine basal to zebras found in the Shungura Formation, Ethiopia and the Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, and dated to around 2.3 mya.[21] E. oldowayensis is identified from remains in Olduvai Gorge dating to 1.8 mya. It is suggested the species was closely related to the Grévy's zebra and may have been its ancestor.[33] Fossil skulls of E. mauritanicus from Algeria which date to around 1 mya appears to show affinities with the plains zebra.[34][35] E. capensis, known as the Cape zebra, appeared around 2 mya and lived throughout southern and eastern Africa and may also have been a relative of the plains zebra.[36][33]

Non-African equines that may have been basal to zebras include E. sansaniensis of Eurasia (circa 2.5 mya) and E. namadicus (circa 2.5 mya) and E. sivalensis (circa 2.0 mya) of the Indian subcontinent.[21] A 2017 mitochondrial DNA study placed the Eurasian E. ovodovi and the subgenus Sussemionus lineage as closer to zebras than to asses.[37]

Hybridisation

Fertile hybrids have been reported in the wild between plains and Grévy's zebra.[38] Hybridisation has also been recorded between the plains and mountain zebra, though it is possible that these are infertile due to the difference in chromosome numbers between the two species.[39] Captive zebras have been bred with horses and donkeys; these are known as zebroids. A zorse is a cross between a zebra and a horse; a zonkey between a zebra and a donkey and a zoni between a zebra and a pony. Zebroids are usually infertile and may suffer from dwarfism.[40]

Characteristics

As with all wild equines, zebra have barrel-chested bodies with tufted tails, elongated faces and long necks with long, erect manes. Their elongated, slender legs end in a single spade-shaped toe covered in a hard hoof. Their dentition is adapted for grazing; they have large incisors that clip grass blades and highly crowned, ridged molars well suited for grinding. Males have spade-shaped canines, which can be used as weapons in fighting. The eyes of zebras are at the sides and far up the head, which allows them to see above the tall grass while grazing. Their moderately long, erect ears are movable and can locate the source of a sound.[8][28][32]

Unlike horses, zebras and asses have chestnut callosities only on their front limbs. In contrast to other living equines, zebra forelimbs are longer than their back limbs.[32] Diagnostic traits of the zebra skull include: its relatively small size with a straight profile, more projected eye sockets, narrower rostrum, reduced postorbital bar, a V-shaped groove separating the metaconid and metastylid of the teeth and both halves of the enamel wall being rounded.[41]

Stripes

.png.webp)

Zebras are easily recognised by their bold black-and-white striping patterns. The belly and legs are white when unstriped, but the muzzle is dark and the skin underneath the coat is uniformly black.[42][43][44] The general pattern is a dorsal line that extends from the forehead to the tail. From there, the stripes stretch downward except on the rump, where they develop species-specific patterns, and near the nose where they curve toward the nostrils. Stripes split above the front legs, creating shoulder stripes. The stripes on the legs, ears and tail are separate and horizontal. Zebras also have complex patterns around the eyes and the lower jaw.[42]

Striping patterns are unique to an individual and heritable.[45] During embryonic development, the stripes appear at eight months, but the patterns may be determined at three to five weeks. For each species there is a point in embryonic development where the stripes are perpendicular to the dorsal and spaced 0.4 mm (0.016 in) apart. However, this happens at three weeks of development for the plains zebra, four weeks for the mountain zebra, and five for Grévy's zebra. The difference in timing is thought to be responsible for the differences in the striping patterns of the different species.[42]

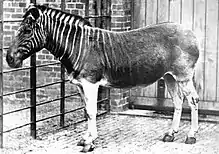

Young or foals are born with brown and white coats, and the brown darkens with age.[26][23] Various mutations of the fur have been documented, from mostly white to mostly black.[46] There have even been morphs with white spots on dark backgrounds.[47] Albino zebras have been recorded in the forests of Mount Kenya, with the dark stripes being blonde.[48] The quagga had brown and white stripes on the head and neck, brown upper parts and a white belly, tail and legs.[49]

Function

The function of stripes in zebras has been discussed among biologists since at least the 19th century.[50] Popular hypotheses include the following:

- The crypsis hypothesis was proposed by Alfred Wallace in 1896 and suggests that the stripes allow the animal to blend in with its environment or break out its outline so predators can not perceive it as a single entity.[51] Zebra stripes may provide particularly good camouflage at nighttime, which is when lions and hyenas are actively hunting.[52] In 1871, Charles Darwin remarked that "the zebra is conspicuously striped, and stripes on the open plains of South Africa cannot afford any protection".[53] Zebras graze in open habitat and do not behave cryptically, being noisy, fast, and social. They do not freeze when detecting a predator. In addition, lions and hyenas do not appear to be able to discern stripes beyond a certain distance in daylight, thus making the stripes useless in disrupting the outline. Stripes also do not appear to make zebras more difficult to find than uniformly coloured animals of similar size, and predators may still be able to detect them by scent or hearing.[54] The camouflaging stripes of woodland living ungulates like bongos and bushbucks are much less vivid and lack the sharp contrast with the background colour.[55][56] In addition, unlike tiger stripes, the spatial frequencies of zebra stripes do not line up with their environment.[57] A 2014 study could not find any correlations between striping patterns and woodland habitats.[56]

- The confusion hypothesis states that the stripes confuse predators, be it by: making it harder to distinguish individuals in a group as well as determining the number of zebras in a group; making it difficult to determine an individual's outline when the group flees; reducing a predator's ability to follow a target during a chase; dazzling an assailant so they have difficultly making contact; or making it difficult for a predator to judge the zebra's size, speed and trajectory via motion dazzle. This theory has been proposed by several biologists since at least the 1970s.[58] A 2014 computer study of zebra stripes found that the motion signals made by zebra stripes give out misleading information and can cause confusion via the wagon-wheel effect or barber pole illusion. The researchers concluded that this could be used against mammalian predators or biting flies.[59] The use of the stripes for confusing against mammalian predators has been questioned. The stripes of zebras could make group size look smaller, and thus more attractive to predators. Zebras also tend to scatter when fleeing from attackers and thus the stripes could not obscure an individual's outline. Lions, in particular, appear to have no difficulty targeting and making contact with zebras when they get close and take them by ambush.[60] In addition, no correlations have been found between the amount of stripes and populations of mammal predators.[56]

- The aposematic hypothesis suggests that the stripes serve as warning colouration as they are recognisable up close. Biologist L. H. Matthews proposed in 1971 that the stripes on the side of the mouth signal to the animal's bite. As with known aposematic mammals, zebras have high predation pressures and make no attempt to hide.[61] However they are frequently preyed on by lions, suggesting that stripes do not deter them but may work on smaller predators. In addition, zebras are not slow and sluggish like known aposematic mammals.[62]

- The social function hypothesis states that stripes serve a role in intraspecific or individual recognition, social bonding, mutual grooming facilitation, or a signal of fitness. Darwin wrote in 1871 that "a female zebra would not admit the addresses of a male ass until he was painted so as to resemble a zebra" while Wallace stated in 1871 that: "The stripes therefore may be of use by enabling stragglers to distinguish their fellows at a distance."[63] Regarding species and individual identification, zebras have limited range overlap with each other and horses can recognise each other using visual cues.[64] In addition, no correlation has been found between striping and social behaviour among equines.[56] There is also no link found between fitness and striping.[64]

- The thermoregulatory hypothesis suggests that stripes help to control a zebra's body temperature. In 1971, biologist H. A. Baldwin noted that black stripes absorbed heat while the white ones reflected it. In 1990, zoologist Desmond Morris proposed that the stripes set up convection currents to cool the animal.[66] A study from 2015 determined that environmental temperature is a strong predictor for zebra striping patterns.[67] Another study from 2019 also concluded that the stripes played a role in regulating heat. Air currents move faster over the heat-absorbing black hairs than the white ones. At the junction of the stripes, the air swirls and cools down the animal. In addition, zebras appear to be able to raise the hair of the black stripes while keeping white hair flat. During the hottest times of the day, the raised hair may help transfer heat from the skin to the hair surface, while during the cooler early morning, the raised black hair can trap air to prevent heat loss.[68] Others have found no evidence that zebras have cooler bodies than other ungulates whose habitat they share, or that striping correlates with temperature.[69][56] A 2018 experimental study which dressed water-filled metal barrels in horse, zebra and cattle hides found that zebra stripes have no effect on thermoregulation.[70]

- The fly protection hypothesis holds that the stripes deter biting flies. Horse flies, in particular, spread diseases that are lethal to equines such as African horse sickness, equine influenza, equine infectious anemia and trypanosomiasis. In addition, zebra hair is shorter or the same length as the mouthparts of horse flies.[56] Caro and colleagues (2019) reported this hypothesis as the "emerging consensus among biologists".[65] It was found that flies were less likely to land on black-and-white striped surfaces than uniformly coloured ones in 1930 by biologist R. Harris.[71] A 2012 study concurred this and concluded that the stripes reflect contrasting light patterns rather than the uniform patterns these insects use to locate food and water.[72] A 2014 study found a correlation between the amount of striping and the presence of horse and tsetse flies. Among wild equines, zebras live in areas with the highest fly activity.[56] Other studies have found that zebras are rarely targeted by these insect species.[73] Caro and colleagues studied captive zebras and horses and found that neither could deter flies from a distance, but zebra stripes made it difficult for flies to make a landing, both for zebras and horses dressed in zebra print coats.[65] A 2020 study found that zebra stripes do not dazzle or work like a barber pole against flies since checkered patterns also repel them.[74] White or light stripes painted on dark bodies have also been found to reduce fly irritations in both cattle and humans.[75][76]

Ecology and behaviour

Zebras may travel or migrate to better watered areas.[26][28] Plains zebras have been recorded travelling 500 km (310 mi) between Namibia and Botswana, the longest land migration of mammals in Africa.[77] When migrating, they appear to rely on some memory of the locations where foraging conditions were best and may predict conditions months after their arrival.[78] Plains zebras are more water-dependent and live in more mesic environments than other species. They seldom wander 10–12 km (6.2–7.5 mi) from a water source.[26][28][79] Grévy's zebras can survive almost a week without water but will drink daily when it is plentiful and conserve water well.[80][23] Mountain zebras can be found at elevations of up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft).[81] Zebras may spend seven hours a day sleeping. During the day, they sleep standing up, while at night they lie down. They regularly rub against trees, rocks, and other objects and roll around in dust for protection against flies and irritation. Except for the mountain zebra, other species can roll over completely.[28]

%252C_vista_a%C3%A9rea_del_delta_del_Okavango%252C_Botsuana%252C_2018-08-01%252C_DD_30.jpg.webp)

Zebras eat primarily grasses and sedges but may also consume bark, leaves, buds, fruits, and roots if their favoured foods are scarce. Compared to ruminants, zebras have a simpler and less efficient digestive system. Nevertheless, they can subsist on lower-quality vegetation. Zebras may spend 60–80% of their time feeding, depending on the availability and quality of vegetation.[8][28] The plains zebra is a pioneer grazer, mowing down the upper, less nutritious grass canopy and preparing the way for more specialised grazers, which depend on shorter and more nutritious grasses below.[82]

Zebras are preyed on mainly by lions. Leopards, cheetahs, spotted hyenas, brown hyenas and wild dogs pose less of a threat to adults.[83] Nile crocodiles also prey on zebras when they near water.[84] Biting and kicking are a zebra's defense tactics. When threatened by lions, zebras flee, and when caught they are rarely effective in fighting off the big cats.[85] The zebra can reach a speed of 68.4 km/h (42.5 mph) compared to 57.6 km/h (35.8 mph) for the lion, but maximum acceleration is respectively 18 km/h (11 mph) and 34.2 km/h (21.3 mph). A lion has to surprise a zebra within the first six seconds of breaking cover.[86] However, a 2018 study found that zebras do not escape lions by speed alone but by laterally turning, especially when the predator is close behind.[87] With smaller predators like hyenas and dogs, zebras may act more aggressively, especially in defense of their young.[88]

Social structure

Zebra species have two basic social structures. Plains and mountain zebras live in stable, closed family groups or harems consisting of one stallion, several mares, and their offspring. These groups have their own home ranges, which overlap, and they tend to be nomadic. Stallions form and expand their harems by recruiting young mares from their natal (birth) harems. The stability of the group remains even when the family stallion dies or is displaced. Plains zebra groups also live in a fission–fusion society. They gather into large herds and may create temporarily stable subgroups within a herd, allowing individuals to interact with those outside their group. Among harem-holding species, this behaviour has otherwise only been observed in primates such as the gelada and the hamadryas baboon.[8][28][89]

Females of these species benefit as males give them more time for feeding, protection for their young, and protection from predators and harassment by outside males. Among females in a harem, a linear dominance hierarchy exists based on the time at which they join the group. Harems travel in a consistent filing order with the high-ranking mares and their offspring leading the groups followed by the next-highest ranking mare and her offspring, and so on. The family stallion takes up the rear. Young of both sexes leave their natal groups as they mature; females are usually herded by outside males to be included as permanent members of their harems.[8][28][89]

In the more arid-living Grévy's zebras, adults have more fluid associations and adult males establish large territories, marked by dung piles, and monopolise the females that enter them. This species lives in habitats with sparser resources and standing water and grazing areas may be separated. Groups of lactating females are able to remain in groups with nonlactating ones and usually gather at foraging areas. The most dominant males establish territories near watering holes, where more sexually receptive females gather. Subdominants have territories farther away, near foraging areas. Mares may wander through several territories but remain in one when they have young. Staying in a territory offers a female protection from harassment by outside males, as well as access to a renewable resource.[8][28][89]

_quarrelling_..._(31709894344).jpg.webp)

In all species, excess males gather in bachelor groups. These are typically young males that are not yet ready to establish a harem or territory.[8][28][89] With the plains zebra, the males in a bachelor group have strong bonds and have a linear dominance hierarchy.[28] Bachelor groups tend to be at the periphery of herds and when the herd moves, the bachelors trail behind.[79] Mountain zebra bachelor groups may also include young females that have recently left their natal group, as well as old males they have lost their harems. A territorial Grévy's zebra stallion may tolerate non-territorial bachelors who wander in their territory, however when a mare in oestrous is present the territorial stallion keeps other stallions at bay. Bachelors prepare for their adult roles with play fights and greeting/challenge rituals, which make up most of their activities.[28]

Fights between males usually occur over mates and involve biting and kicking. In plains zebra, stallions fight each other over recently matured mares to bring into their group and her family stallion will fight off other males trying to abduct her. As long as a harem stallion is healthy, he is not usually challenged. Only unhealthy stallions have their harems taken over, and even then, the new stallion gradually takes over, pushing the old one out without a fight. Agonistic behaviour between male Grévy's zebras occurs at the border of their territories.[28]

Communication

.jpg.webp)

When meeting for the first time, or after they have separated, individuals may greet each other by rubbing and sniffing their noses followed by rubbing their cheeks, moving their noses along their bodies and sniffing each other's genitals. They then may rub and press their shoulders against each other and rest their heads on one another. This greeting is usually performed among harem or territorial males or among bachelor males playing.[28] Plains and mountain zebras strengthen their social bonds with grooming. Members of a harem nip and scrape along the neck, shoulder, and back with their teeth and lips. Grooming usually occurs between mothers and foals and between stallions and mares. Grooming shows social status and eases aggressive behaviour.[28][90] Although Grévy's zebras do not perform social grooming, they do sometimes rub against another individual.[23]

Zebras produce a number of vocalisations and noises. The plains zebra has a distinctive, high-pitched contact call (commonly called "barking") heard as "a-ha, a-ha, a-ha" or "kwa-ha, kaw-ha, ha, ha".[26] The call of the Grévy's zebra has been described as "something like a hippo's grunt combined with a donkey's wheeze", while the mountain zebra is relatively silent. Loud snorting in zebras is associated with alarm. Squealing is usually made when in pain, but bachelors also squeal while play fighting. Zebras also communicate with visual displays, and the flexibility of their lips allows them to make complex facial expressions. Visual displays also incorporate the positions of the head, ears, and tail. A zebra may signal an intention to kick by laying back its ears and sometimes lashing the tail. Flattened ears, bared teeth, and abrupt movement of the heads may be used as threatening gestures, particularly among stallions.[28]

Reproduction and parenting

Among plains and mountain zebras, the adult females mate only with their harem stallion, while in Grévy's zebras, mating is more promiscuous and the males have larger testes for sperm competition.[8][91] Oestrus in female zebras lasts five to ten days; physical signs include frequent urination, flowing mucus, and swollen, everted (inside out) labia. In addition, females in oestrous will stand with their hind legs spread and raise their tails when in the presence of a male. Males assess the female's reproductive state with a curled lip and bared teeth (flehmen response) and the female will solicit mating by backing in. The length of gestation varies by species; it is roughly 11–13 months, and most mares come into oestrus again within a few days after foaling, depending on conditions.[28] In harem-holding species, oestrus in a female becomes less noticeable to outside males as she gets older, hence competition for older females is virtually nonexistent.[26]

_mare_and_foal_suckling_..._(31281408687).jpg.webp)

Usually, a single foal is born, which is capable of running within an hour of birth.[8] A newborn zebra will follow anything that moves, so new mothers prevent other mares from approaching their foals while imprinting their own striping pattern, scent and vocalisation on them.[23] Within a few weeks, foals attempt to graze, but may continue to nurse for eight to thirteen months.[8] Living in an arid environment, Grévy's zebras have longer nursing intervals and do not drink water until they are three months old.[92]

In plains and mountain zebras, foals are cared for mostly by their mothers, but if threatened by pack-hunting hyenas and dogs, the entire group works together to protect all the young. The group forms a protective front with the foals in the centre, and the stallion will rush at predators that come too close.[28] In Grévy's zebras, mothers may gather into small groups and leave their young in "kindergartens" guarded by a territorial male while searching for water.[92] A stallion may look after a foal in his territory to ensure that the mother stays, though it may not be his.[89] By contrast, plains zebra stallions are generally intolerant of foals that are not theirs and may practice infanticide and feticide via violence to the pregnant mare.[93]

Human relations

Cultural significance

.jpg.webp)

With their distinctive black-and-white stripes, zebras are among the most recognisable mammals. They have been associated with beauty and grace, with naturalist Thomas Pennant describing them in 1781 as "the most elegant of quadrupeds". Zebras have been popular in photography, with some wildlife photographers describing them as the most photogenic animal. Zebras have become staples in children's stories and wildlife-themed art, such as depictions of Noah's Ark. They are known for being among the last animals to be featured in the dictionary and in children's alphabet books where they are often used to represent the letter 'Z'.[94] Zebra stripes are also popularly used for body paintings, dress, furniture and architecture.[95]

Zebras have been featured in African art and culture for millennia. They are depicted in rock art in Southern Africa dating from 28,000 to 20,000 years ago, though not as commonly as antelope species like eland. How the zebra got its stripes has been the subject of folk tales, some of which involve it being scorched by fire. The Maasai proverb "a man without culture is like a zebra without stripes" has become popular in Africa and beyond. The San people associated zebra stripes with water, rain and lighting because of its dazzling pattern, and water spirits were conceived of having zebra stripes.[96]

For the Shona people, the zebra is a totem animal and is praised in a poem as an "iridescent and glittering creature". Its stripes have symbolised the joining of male and female and at the ruined city of Great Zimbabwe, zebra stripes decorate what is believed to be a domba, a premarital school meant to initiate girls into adulthood. In the Shona language, the name madhuve means "woman/women of the zebra totem" and is a given name for girls in Zimbabwe. The plains zebra is the national animal of Botswana and zebras have been depicted on stamps during colonial and post-colonial Africa. For people of the African diaspora, the zebra represented the politics of race and identity, being both black and white.[97]

In cultures outside of its range, the zebra has been thought of as a more exotic alternative to the horse; the comic book character Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, is depicted riding a zebra and explorer Osa Johnson was photographed riding one.[98] The film Racing Stripes features a captive zebra ostracised from the horses and ending up being ridden by a rebellious girl.[99] Zebras have been featured as characters in animated films like Khumba, The Lion King and the Madagascar films and television series such as Zou.[100]

Zebras have been popular subjects for paintings, particularly for abstract, modernist and surrealist artists. Notable zebra art includes Christopher Wood's Zebra and Parachute, Lucian Freud's The Painter's Room and Quince on a Blue Table and the various paintings of Mary Fedden and Sidney Nolan. Victor Vasarely depicted zebras as mere bands of black and white and joined together in a jigsaw puzzle fashion. Carel Weight's Escape of the Zebra from the Zoo during an Air Raid was based on a real life incident of a zebra escaping during the bombing of London Zoo and consists of four panels like a comic book.[101] Zebras have lent themselves to products and advertisements, notably for 'Zebra Grate Polish' cleaning supplies by British manufacturer Reckitt and Sons and Japanese pen manufacturer Zebra Co., Ltd..[102]

Captivity

Zebras have been kept in captivity since at least the Roman Empire.[103] In later times, captive zebras have been shipped around the world, often for diplomatic reasons. In 1261, Sultan Baibars of Egypt established an embassy with Alfonso X of Castile and sent a zebra and other exotic animals as gifts. In 1417, a zebra was sent to the Yongle Emperor of China from Somalia as a gift for the Chinese people. The fourth Mughal emperor Jahangir received a zebra from Ethiopia in 1620 and commissioned a painting of the animal, which was completed by Ustad Mansur. In the 1670s, Ethiopian Emperor Yohannes I exported two zebras to the Dutch governor of Jakarta. These animals would eventually be given by the Dutch to the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan.[104]

When Queen Charlotte received a zebra as a wedding gift in 1762, the animal became a source of fascination for the people of Britain. Many flocked to see it at its paddock at Buckingham Palace. It soon became the subject of humour and satire, being referred to as "The Queen's Ass", and was the subject of an oil painting by George Stubbs in 1763. The zebra also gained a reputation for being ill-tempered and kicked at visitors.[105] In 1882, Ethiopia sent a zebra to French president Jules Grévy, and the species it belonged to was named in his honour.[9]

Attempts to domesticate zebras were largely unsuccessful. It is possible that having evolved under pressure from the many large predators of Africa, including early humans, they became more aggressive, thus making domestication more difficult.[106] However, zebras have been trained and tamed throughout history. In Rome, zebras are recorded to have pulled chariots during gladiator games starting in the reign of Caracalla (198 to 217 AD).[107] In the late 19th century, the zoologist Walter Rothschild trained some zebras to draw a carriage in England, which he drove to Buckingham Palace to demonstrate the tame character of zebras to the public. However, he did not ride on them as he realised that they were too small and aggressive.[108] In the early 20th century, German colonial officers in German East Africa tried to use zebras for both driving and riding, with limited success.[109]

Conservation

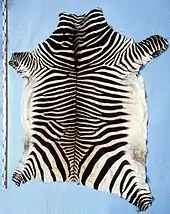

As of 2016–2019, the IUCN Red List of mammals lists the Grévy's zebra as endangered, the mountain zebra as vulnerable and the plains zebra as near-threatened. Grévy's zebra populations are estimated at less than 2,000 mature individuals, but they are stable. Mountain zebras number near 35,000 individuals and their population appears to be increasing. Plains zebra are estimated to number 150,000–250,000 with a decreasing population trend. Human intervention has fragmented zebra ranges and populations. Zebras are threatened by hunting for their hide and meat, and habitat change from farming. They also compete with livestock for food and water and fencing blocks their migration routes.[110][111][112] Civil wars in some countries have also caused declines in zebra populations.[113] By the beginning of the 20th century, zebra skins were valued commodities and were typically used as rugs. In the 21st century, zebra hides still sell for $1,000 and $2,000, and they are taken by trophy hunters.[114] Zebra meat was mainly eaten by European colonisers; among African cultures only the San are known to eat it regularly.[115]

The quagga population was hunted by early Dutch settlers and later by Afrikaners to provide meat or for their skins. The skins were traded or used locally. The quagga was probably vulnerable to extinction due to its limited distribution, and it may have competed with domestic livestock for forage. The last known wild quagga died in 1878.[116] The last captive quagga, a female in Amsterdam's Natura Artis Magistra zoo, lived there from 9 May 1867 until it died on 12 August 1883.[117] The Cape mountain zebra, a subspecies of mountain zebra, was driven to near extinction by hunting and habitat loss with less than 50 individuals by the 1950s. Conservation efforts by the South African National Parks have since allowed the populations to grow to over 2,600 by the 2010s.[118]

Zebras can be found in numerous protected areas. Important areas for the Grévy's zebra include Yabelo Wildlife Sanctuary and Chelbi Sanctuary in Ethiopia and Buffalo Springs, Samburu and Shaba National Reserves in Kenya.[110] Protected areas for the plains zebra include the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, Tsavo and Masai Mara in Kenya, Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe, Etosha National Park in Namibia, and Kruger National Park in South Africa.[112] Mountain zebras are protected in Mountain Zebra National Park, Karoo National Park and Goegap Nature Reserve in South Africa as well as Etosha and Namib-Naukluft Park in Namibia.[111][119]

See also

- Fauna of Africa

- Lord Morton's mare

- Zebra patterning

- Zebra striping (computer graphics)

- Zonkey (Tijuana) – a donkey painted with zebra stripes

Explanatory notes

- Pronounced /ˈziːbrə/ ZEE-brə or /ˈzɛbrə/ ZEB-rə[1]

Citations

- "Zebra". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Zebra". Lexico. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- Nores, Carlos; Muñiz, Arturo Morales; Rodríguez, Laura Llorente; Bennett, E. Andrew; Geigl, Eva-María (2015). "The Iberian Zebro: what kind of a beast Was It?". Anthropozoologica. 50: 21–32. doi:10.5252/az2015n1a2. S2CID 55004515.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, p. 54.

- Wells, John (1997). "Our Changing Pronunciation". Transactions of the Yorkshire Dialect Society. XIX: 42–48. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- "Zebra". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Animal Collectives". Columbia Journalism Review. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- Rubenstein, D. I. (2001). "Horse, Zebras and Asses". In MacDonald, D. W. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 468–473. ISBN 978-0-7607-1969-5.

- Prothero, D. R.; Schoch, R. M. (2003). Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: The Evolution of Hoofed Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 216–218. ISBN 978-0-8018-7135-1.

- "Hippotigris". ITIS. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- "Dolichohippus". ITIS. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- Groves, C. P.; Bell, C. H. (2004). "New investigations on the taxonomy of the zebras genus Equus, subgenus Hippotigris". Mammalian Biology. 69 (3): 182–196. doi:10.1078/1616-5047-00133.

- Vilstrup, Julia T.; Seguin-Orlando, A.; Stiller, M.; Ginolhac, A.; Raghavan, M.; Nielsen, S. C. A.; et al. (2013). "Mitochondrial phylogenomics of modern and ancient equids". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e55950. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...855950V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055950. PMC 3577844. PMID 23437078.

- Groves, C.; Grubb, P. (2011). Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4214-0093-8.

- Hofreiter, M.; Caccone, A.; Fleischer, R. C.; Glaberman, S.; Rohland, N.; Leonard, J. A. (2005). "A rapid loss of stripes: The evolutionary history of the extinct quagga". Biology Letters. 1 (3): 291–295. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0323. PMC 1617154. PMID 17148190.

- Pedersen, Casper-Emil T.; Albrechtsen, Anders; Etter, Paul D.; Johnson, Eric A.; Orlando, Ludovic; Chikhi, Lounes; Siegismund, Hans R.; Heller, Rasmus (2018). "A southern African origin and cryptic structure in the highly mobile plains zebra". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (3): 491–498. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0453-7. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 29358610. S2CID 3333849.

- Forstén, Ann (1992). "Mitochondrial‐DNA timetable and the evolution of Equus: of molecular and paleontological evidence" (PDF). Annales Zoologici Fennici. 28: 301–309.

- Ryder, O. A.; George, M. (1986). "Mitochondrial DNA evolution in the genus Equus" (PDF). Molecular Biology and Evolution. 3 (6): 535–546. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040414. PMID 2832696.

- Orlando, L.; Ginolhac, A.; Zhang, G.; Froese, D.; Albrechtsen, A.; Stiller, M.; et al. (July 2013). "Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse". Nature. 499 (7456): 74–78. Bibcode:2013Natur.499...74O. doi:10.1038/nature12323. PMID 23803765. S2CID 4318227.

- Forstén, Ann (1992). "Mitochondrial‐DNA timetable and the evolution of Equus: of molecular and paleontological evidence" (PDF). Annales Zoologici Fennici. 28: 301–309.

- Bernor, R. L.; Cirilli, O.; Jukar, A. M.; Potts, R.; Buskianidze, M.; Rook, L. (2019). "Evolution of early Equus in Italy, Georgia, the Indian Subcontinent, East Africa, and the origins of African zebras". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00166.

- Caro 2016, p. 9.

- Churcher, C. S. (1993). "Equus grevyi" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 453 (453): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504222. JSTOR 3504222.

- Caro 2016, p. 15.

- Caro 2016, p. 14.

- Grubb, P. (1981). "Equus burchellii". Mammalian Species. 157 (157): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3503962. JSTOR 3503962.

- Caro 2016, p. 13.

- Estes, R. (1991). The Behavior Guide to African Mammals. University of California Press. pp. 235–248. ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- Caro 2016, pp. 12–13.

- Caro 2016, p. 11.

- Penzhorn, B. L. (1988). "Equus zebra". Mammalian Species. 314 (314): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3504156. JSTOR 3504156.

- Rubenstein, D. I. (2011). "Family Equidae: Horses and relatives". In Wilson, D. E.; Mittermeier, R. A.; Llobet, T. (eds.). Handbook of the Mammals of the World. 2: Hoofed Mammals (1st ed.). Lynx Edicions. pp. 106–111. ISBN 978-84-96553-77-4.

- Churcher, C. S. (2006). "Distribution and history of the Cape zebra (Equus capensis) in the Quarternary of Africa". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa. 61 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1080/00359190609519957. S2CID 84203907.

- Azzaroli, A.; Stanyon, R. (1991). "Specific identity and taxonomic position of the extinct Quagga". Rendiconti Lincei. 2 (4): 425. doi:10.1007/BF03001000. S2CID 87344101.

- Eisenmann, V. (2008). "Pliocene and Pleistocene equids: palaeontology versus molecular biology". Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 256: 71–89.

- Badenhorst, S.; Steininger, C. M. (2019). "The Equidae from Cooper's D, an early Pleistocene fossil locality in Gauteng, South Africa". PeerJ. 7: e6909. doi:10.7717/peerj.6909. PMC 6525595. PMID 31143541.

- Druzhkova, Anna S.; Makunin, Alexey I.; Vorobieva, Nadezhda V.; Vasiliev, Sergey K.; Ovodov, Nikolai D.; Shunkov, Mikhail V.; Trifonov, Vladimir A.; Graphodatsky, Alexander S. (January 2017). "Complete mitochondrial genome of an extinct Equus (Sussemionus) ovodovi specimen from Denisova cave (Altai, Russia)". Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2 (1): 79–81. doi:10.1080/23802359.2017.1285209. ISSN 2380-2359. PMC 7800821. PMID 33473722.

- Cordingley, J. E.; Sundaresan, S. R.; Fischhoff, I. R.; Shapiro, B.; Ruskey, J.; Rubenstein, D. I. (2009). "Is the endangered Grevy's zebra threatened by hybridization?". Animal Conservation. 12 (6): 505–513. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2009.00294.x.

- Giel, E.-M.; Bar-David, S.; Beja-Pereira, A.; Cothern, E. G.; Giulotto, E.; Hrabar, H.; Oyunsuren, T.; Pruvost, M. (2016). "Genetics and Paleogenetics of Equids". In Ransom, J. I.; Kaczensky, P. (eds.). Wild Equids: Ecology, Management, and Conservation. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4214-1909-1.

- Bittel, Jason (19 June 2015). "Hold Your Zorses: The sad truth about animal hybrids". Slate.com. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Badam, G. L.; Tewari, B. S. (1974). "On the zebrine affinities of the Pleistocene horse Equus sivalensis, falconer and cautley". Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. 34 (1/4): 7–11. JSTOR 42931011.

- Bard, J. (1977). "A unity underlying the different zebra patterns". Journal of Zoology. 183 (4): 527–539. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1977.tb04204.x.

- Langley, Liz (4 March 2017). "Do Zebras Have Stripes On Their Skin?". National Geographic. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Caro 2016, pp. 14–15.

- Caro 2016, pp. 7, 19.

- Kingdon, J. (1988). East African Mammals: An Atlas of Evolution in Africa. 3, Part B: Large Mammals. University of Chicago Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-226-43722-4.

- Caro 2016, p. 20.

- "Extremely Rare 'Blonde' Zebra Photographed". National Geographic. 29 March 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. 1. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1024–1025. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Caro 2016, p. 1.

- Caro 2016, pp. 2–3, 23, 38.

- Caro 2016, pp. 44–45.

- Caro 2016, p. 3.

- Caro 2016, pp. 46–48.

- Caro 2016, p. 50.

- Caro, T.; Izzo, A.; Reiner, R. C.; Walker, H.; Stankowich, T. (2014). "The function of zebra stripes". Nature Communications. 5: 3535. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3535C. doi:10.1038/ncomms4535. PMID 24691390.

- Godfrey, D.; Lythgoe, J. N.; Rumball, D. A. (1987). "Zebra stripes and tiger stripes: the spatial frequency distribution of the pattern compared to that of the background is significant in display and crypsis". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 32 (4): 427–433. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.1987.tb00442.x.

- Caro 2016, pp. 72–81, 86.

- How, M. J.; Zanker, J. M. (2014). "Motion camouflage induced by zebra stripes". Zoology. 117 (3): 163–170. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2013.10.004. PMID 24368147.

- Caro 2016, pp. 80, 92.

- Caro 2016, pp. 55, 57–58.

- Caro 2016, p. 68.

- Caro 2016, pp. 6, 139–148.

- Caro 2016, p. 150.

- Caro, T.; Argueta, Y.; Briolat, E. S.; Bruggink, J.; Kasprowsky, M.; Lake, J.; Richardson, S.; How, M. (2019). "Benefits of zebra stripes: behaviour of tabanid flies around zebras and horses". PLOS ONE. 14 (2): e0210831. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1410831C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210831. PMC 6382098. PMID 30785882.

- Caro 2016, p. 24.

- Larison, Brenda; Harrigan, Ryan J.; Thomassen, Henri A.; Rubenstein, Daniel I.; Chan-Golston, Alec M.; Li, Elizabeth; Smith, Thomas B. (2015). "How the zebra got its stripes: a problem with too many solutions". Royal Society Open Science. 2 (1): 140452. Bibcode:2015RSOS....240452L. doi:10.1098/rsos.140452. PMC 4448797. PMID 26064590.

- Cobb, A.; Cobb, S. (2019). "Do zebra stripes influence thermoregulation?". Journal of Natural History. 53 (13–14): 863–879. doi:10.1080/00222933.2019.1607600. S2CID 196657566.

- Caro 2016, pp. 158–161.

- Horváth, Gábor; Pereszlényi, Ádám; Száz, Dénes; Barta, András; Jánosi, Imre M.; Gerics, Balázs; Åkesson, Susanne (2018). "Experimental evidence that stripes do not cool zebras". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 9351. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.9351H. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-27637-1. PMC 6008466. PMID 29921931.

- Caro 2016, p. 5.

- Egri, Ádám; Blahó, Miklós; Kriska, György; Farkas, Róbert; Gyurkovszky, Mónika; Åkesson, Susanne; Horváth, Gábor (2012). "Polarotactic tabanids find striped patterns with brightness and/or polarization modulation least attractive: an advantage of zebra stripes". Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (5): 736–745. doi:10.1242/jeb.065540. PMID 22323196.

- Caro 2016, pp. 196–197.

- How, M. J.; Gonzales, D.; Irwin, A.; Caro, T. (2020). "Zebra stripes, tabanid biting flies and the aperture effect". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1933). doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.1521. PMC 7482270. PMID 32811316.

- Kojima, T.; Oishi, K.; Matsubara, Y.; Uchiyama, Y.; Fukushima, Y. (2020). "Cows painted with zebra-like striping can avoid biting fly attack". PLOS ONE. 15 (3): e0231183. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231183. PMC 7098620. PMID 32214400.

- Horváth, G.; Pereszlényi, Á.; Åkesson, S.; Kriska, G. (2019). "Striped bodypainting protects against horseflies". Royal Society Open Science. 6 (1): 181325. Bibcode:2019RSOS....681325H. doi:10.1098/rsos.181325. PMC 6366178. PMID 30800379.

- Naidoo, R.; Chase, M. J.; Beytall, P.; Du Preez, P. (2016). "A newly discovered wildlife migration in Namibia and Botswana is the longest in Africa". Oryx. 50 (1): 138–146. doi:10.1017/S0030605314000222.

- Bracis, C.; Mueller, T. (2017). "Memory, not just perception, plays an important role in terrestrial mammalian migration". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1855): 20170449. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.0449. PMC 5454266. PMID 28539516.

- Skinner, J. D.; Chimimba, C. T. (2005). "Equidae". The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 544–546. ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5.

- Youth, H. (November–December 2004). "Thin stripes on a thin line". Zoogoer. 33. Archived from the original on 26 October 2005.

- Woodward, Susan L. (2008). Grassland Biomes. Greenwood Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-313-33999-8.

- Pastor, J.; Cohen, U.; Hobbs, T. (2006). "The roles of large herbivores in ecosystem nutrient cycles". In Danell, K. (ed.). Large Herbivore Ecology, Ecosystem Dynamics and Conservation. Cambridge University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-521-53687-5.

- Caro 2016, pp. 61–63.

- Kennedy, A. S., & Kennedy, V. (2013). Animals of the Masai Mara. Princeton University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0691156019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Caro 2016, p. 61–62.

- Caro 2016, p. 92.

- Wilson, A.; Hubel, T.; Wilshin, S.; et al. (2018). "Biomechanics of predator–prey arms race in lion, zebra, cheetah and impala" (PDF). Nature. 554 (7691): 183–188. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..183W. doi:10.1038/nature25479. PMID 29364874. S2CID 4405091.

- Caro 2016, p. 63.

- Rubenstein, D. I. (1986). "Ecology and sociality in horses and zebras". In Rubenstein, D. I.; Wrangham, R. W. (eds.). Ecological Aspects of Social Evolution (PDF). Princeton University Press. pp. 282–302. ISBN 978-0-691-08439-8.

- Caro 2016, p. 143.

- Ginsberg, R; Rubenstein, D. I. (1990). "Sperm competition and variation in zebra mating behavior" (PDF). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 26 (6): 427–434. doi:10.1007/BF00170901. S2CID 206771095.

- Becker, C. D.; Ginsberg, J. R. (1990). "Mother-infant behaviour of wild Grevy's zebra". Animal Behaviour. 40 (6): 1111–1118. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80177-0. S2CID 54252836.

- Pluháček, J; Bartos, L (2005). "Further evidence for male infanticide and feticide in captive plains zebra, Equus burchelli" (PDF). Folia Zoologica-Praha. 54 (3): 258–262.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 10–13, 189.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 40–41, 134–140.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 37–44.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 45–50.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 166–168, 192–194.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, p. 194.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 188, 200–201.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 141–149.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 128–131.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 55–57.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 58–61, 65–66.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 76–78, 81.

- "The Story Of... Zebra and the Puzzle of African Animals". PBS. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, p. 56.

- Young, R. (23 May 2013). "Can Zebras Be Domesticated and Trained?". Slate. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- Gann, L.; Duignan, Peter (1977). The Rulers of German Africa, 1884–1914. Stanford University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-8047-6588-6.

- Rubenstein, D.; Low Mackey, B.; Davidson, Z. D.; Kebede, F.; King, S. R. B. (2016). "Equus grevyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Gosling, L. M.; Muntifering, J.; Kolberg, H.; Uiseb, K.; King, S. R. B. (2016). "Equus zebra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- King, S. R. B.; Moehlman, P. D. (2016). "Equus quagga". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Hack, Mace A.; East, Rod; Rubenstein, Dan J. (2002). "Status and Action Plan for the Plains Zebra (Equus burchelli)". In Moehlman, P. D. (ed.). Equids. Zebras, Asses and Horses. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. IUCN. p. 51. ISBN 978-2-8317-0647-4.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, pp. 132–133.

- Plumb & Shaw 2018, p. 41.

- Weddell, B. J. (2002). Conserving Living Natural Resources: In the Context of a Changing World. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-521-78812-0.

- Van Bruggen, A. C. (1959). "Illustrated notes on some extinct South African ungulates". South African Journal of Science. 55: 197–200.

- Kotzé, A.; Smith, R. M.; Moodley, Y.; Luikart, G.; Birss, C.; Van Wyk, A. M.; Grobler, J. P.; Dalton, D. L. (2019). "Lessons for conservation management: Monitoring temporal changes in genetic diversity of Cape mountain zebra (Equus zebra zebra)". PLOS ONE. 14 (7): e0220331. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1420331K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220331. PMC 6668792. PMID 31365543.

- Hamunyela, Elly. "The status of Namibia's Hartmann's zebra". Travel News Namibia. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

General bibliography

- Caro, Tim (2016). Zebra Stripes. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-41101-9.

- Plumb, C.; Shaw, S. (2018). Zebra. Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780239712.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zebras. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Zebra. |

- The Quagga Project—An organisation that selectively breeds zebras to recreate the hair coat pattern of the quagga