ʻAkohekohe

The ʻākohekohe (Palmeria dolei), or crested honeycreeper, is a species of Hawaiian honeycreeper. It is endemic to the island of Maui in Hawaiʻi. The ʻākohekohe is susceptible to mosquito‐transmitted avian malaria (Plasmodium relictum) and only breeds in high‐elevation wet forests (> 1715 m).[2]

| ʻĀkohekohe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | Palmeria Rothschild, 1893 |

| Species: | P. dolei |

| Binomial name | |

| Palmeria dolei (Wilson, 1891) | |

Description

The ʻākohekohe is the largest honeycreeper on Maui, at 6.5 to 7 inches (17 to 18 cm) in length.[3] The adults are a glossy black with whitish feathers and stripes going down its side. The underparts are whitish black while the top has orange feathers sticking from wings. The feathers behind the eyes are a reddish color, and have a stream of cream colored feathers coming from the eyes. One of the things that most people recognize about this bird is its whitish gold colored feather crest on its head. The younger birds are brownish black and they do not have the orange feathers of the parents. The legs and bills are a blackish color.

Song

It has a variety of songs. The most well known of the calls is a pair of whee-o, whee-o, being repeated over and over again. Also another well known song is a descending thrill which is done about five seconds apart. It songs include a low chuckling sound, tjook, tjook, chouroup or a rarer song, hur-hur-hur-gluk-gluk-gluk.

Diet

The ʻākohekohe is a nectarivore that feeds on the flowers of ʻōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha) high up in the canopy. It is an aggressive bird and will drive away competing nectarivores, such as the related ʻapapane and ʻiʻiwi. When ʻōhiʻa lehua blossoms are limited, it will eat insects, fruit, and nectar from other plants. The ʻākohekohe will forage in the understory if necessary, where food plants include ʻākala (Rubus hawaiensis).[3]

Habitat and distribution

Its natural habitat is wet forests dominated by koa (Acacia koa) and ʻōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha) on the windward side of Haleakalā at elevations of 4,200 to 7,100 feet (1,300 to 2,200 m). During a search for the species in the east Maui forests, there were a record of 415 observations over an area of 11,000 acres (45 km2) and at elevations from 4,200 to 7,100 feet (1,300 to 2,200 m) above sea level. It has been estimated that there are a total of 3,800 ʻākohekohe left on Maui in two populations separated by the Koʻolau Gap.

Threats

The ʻākohekohe currently survives only on Maui, but also lived on the eastern side of the island of Molokaʻi until 1907. This bird was common on both islands at the start of the 20th century. It was thought to be extinct after that—however, in 1945 a small population was discovered in the National Area Reserve on Halakea in Maui. Over the course of the millennia, the population has decreased. The first inhabitants, the Polynesians, deforested much of the islands to create farmland, which destroyed a large amount of the birds' habitat. When the Europeans arrived, the land and the animals dependent on it decreased further. The Europeans brought with them three species of rats. The rats attacked the eggs, chicks, and adults of many bird species. They also ate the birds' food sources. Another factor that lead to the decline of the ʻākohekohe was its unusual appearance, which made it very desirable to collectors. Later, in the 1900s, mosquitoes were introduced to the Hawaiian Islands and inflicted deadly diseases on the birds, which lacked resistance to the pathogens. Finally, humans released invasive birds which competed with the native birds for food, water, shelter and a place to raise their young.

Conservation

According to the Federal Endangered Species Act, this bird is protected by law along with its habitat. The bird was included in the act in March 1967. It was also a part of many other documents including the Maui-Molokai Forest Bird Recovery Plan in 1967, by the Fish and Wildlife Service. It will serve as a guideline to protect the indigenous life of Maui and Molokaʻi. The final recovery plan in 1984 continues the last, keeping eyes on the species and eradicating any ungulates that are introduced into the area that can harm and or disturb the ʻākohekohe and other native forest birds in Maui's forests.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palmeria dolei. |

References

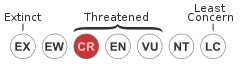

- BirdLife International (2013). "Palmeria dolei". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wang, A.X. et al. (2020) Divergent movement patterns of adult and juvenile ‘Akohekohe, an endangered Hawaiian Honeycreeper. Journal of Field Ornithology. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofo.12348

- "Crested Honeycreeper (Palmeria dolei)". Native Forest Birds of Hawaiʻi. Conservation Hawaii. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

External links

- Species factsheet - BirdLife International

- Videos, photos and sounds - Internet Bird Collection