A-not-A question

In linguistics, an A-not-A question, also known as an A-neg-A question, is a polar question that offers two opposite possibilities for the answer. Predominantly researched in Sinitic languages, the A-not-A question offers a choice between an affirmative predicate and its negative counterpart. They are functionally regarded as a type of "yes/no" question, though A-not-A questions have a unique interrogative type pattern which does not permit simple yes/no answers and instead requires a response that echoes the original question. Therefore, to properly answer the query, the recipient must select the positive (affirmative form "A") or negative (negative predicate form "not-A") version and use it in the formation of their response.[1] A-not-A questions are often interpreted as having a "neutral" presupposition or are used in neutral contexts,[2] meaning that the interrogator does not presume the truth value of the proposition expressed in the question. The overarching principle is the value-neutral contrast of the positive and negative forms of a premise. The label of "A-not-A question" may refer to the specific occurrence of these question types in Mandarin or, more broadly, to encompass other dialect-specific question types such as kam questions in Taiwanese Mandarin or ka questions in Singapore Teochew (ST), though these types possess unique properties and can even occur in complementary distribution with the A-not-A question type.[3][4]

Forms

The wider category of A-not-A questions contains multiple distinct forms. These forms are differentiated on the basis of the location of the Negation constituent and the presence or absence of duplicate material.

A-not-A form

This is the most atomic form of the A-not-A question, which contains two identical instances of the constituent A separated by negation.

AB-not-AB form

This is a more complex form, containing two instances of the complex constituent AB separated by the negation. AB may represent an embedded clause, a subject joined with a prepositional phrase, or a verb phrase containing a DP.

A-not-AB form

This form contains two unique constituents, A and AB, separated by the negation. A and AB are similar in that AB contains the entire content of A, but constituents are present in AB that are not present in A.

AB-not-A form

This form is similar to the A-not-AB form, but the more complex constituent AB occurs before the negation.

a-not-A form

This form is only found in instances where A is disyllabic constituent with initial syllable a, and the two constituents are separated by negation.

a-not-AB form

This form is similar to the a-not-A form with a representing the initial syllable of A and the two separated by negation, but A is joined to another constituent to form the complex constituent AB.

Similar forms in English

For the English question (1.a) "Are you happy or sad?", the response to this question must be an echo answer, stating either "I am happy," or the acceptable alternative, "I am sad". In other words, this sentence is a leading question, where the speaker has an expectation as to what the answer will be. In contrast, (1.b) "Are you happy or not?" is a neutral question where the answer to this can be yes or no in response to the first and more explicitly stated alternative.[5]

(1.a) Q: Are you happy or sad?

A: I am happy.

I am sad.

(1.b) Q: Are you happy or not (happy)?

A: Yes.

No.

A-not-A questions are not usually used in English, but the following example shows how A-not-A questions are answered.

(2) Q: Did John eat beans or not?

A: (Yes,) John ate beans.

(No,) John didn't eat beans.

*Yes.

*No.[6]

As seen in this example, simply answering "Yes" or "No" does not suffice as a response to the question. This question must be answered in the "A" or "not A" form. If this question was asked in the A-not-A pattern, its direct form would be "Did John eat or not eat the beans?". However, the above examples also illustrate that A-not-A type questions in English usually contain some comparative operator such as "or" which is not seen in the Sinitic forms. There is also no significant evidence of either of the disyllabic A-not-A forms in English. These factors complicate the inclusion of English in the set of languages that contain the A-not-A question type, and though there are close English approximations in some cases, The A-not-A question is more accurately exemplified in Sinitic languages.

Approximations

Below are examples of English approximations of the A-not-A question. They are similar to the Sinitic A-not-A in that they present two possibilities and require an echoed response. However, they include an extra segment ("or" in the below examples) in order to read grammatically, which changes these approximations to an alternative question (AltQ) type. This extra segment is not seen in Sinitic A-not-A questions, and in fact the Mandarin segment 還是 haishi 'or' is used to contrast the syntax of the A-not-A form and demonstrate the latter's sensitivity to islands. Nevertheless, for the convenience of understanding this phenomenon from the perspective of an English speaker, the below examples are included to provide context.

A-not-A form

(1) Was John at the party or not at the party?

AB-not-A form

(2) Was John at the party last night or not at the party?

A-not-AB form

(4) Was John at the party or not at the party last night?

AB-not-AB form

(3) Was John at the party last night or not at the party last night?

In Sinitic

NQ Morpheme

It is proposed that the A-not-A sequence is morpheme created by the reduplication of the interrogative morpheme (represented by the A in A-not-A).[4] Though the specific syntactic location of this morpheme is not agreed upon, it is generally accepted that the A-not-A sequence is essentially a word formed by the concatenation of an abstract question morpheme and this duplicated predicate, which likens it to a VP-proclitic. This Morpheme is referred to as NQ in order to represent its character as negative and interrogative.

Similarity to kam-type questions

An extensive cross-dialectic survey conducted in 1985 concluded that the Taiwanese question particle kam appears in the same contexts as the hypothesized Mandarin NQ.[3] From this, it was concluded that kam-type questions and A-not-A questions are in complementary distribution: a language either has kam-type questions or A-not-A questions but not both. It was also interpreted that kam and NQ are "different morphological exponents of the same underlying morpheme".[4]

Movement, sensitivity, and parallels to weishenme 'why'

Unlike the yes/no question type formed using the segment "ma", the A-not-A question can be embedded, and may scope beyond its own clause. This scoping may be blocked if the original location of NQ and its intended final location are separated by an island boundary.[7] These distributional characteristics of NQ are parallel to non-nominal adjunct question particle weishenme 'why'. Due to the uncontroversial nature of the movement-based analysis of weishenme, the similarity of the NQ to weishenme implies that NQ amy be subject to the same analysis of its movement.

Sensitivity to islands

The dominant view on A-not-A questions is that NQ is similar to a wh-word and related by the movement of NQ.[8][7] This movement is not seen in alternative-type questions using haishi 'or', and therefore delineates A-not-A questions from alternative questions in terms of structure. Due to this syntactic differentiation, A-not-A questions may be contrasted with haishi questions for the purpose of revealing island sensitivity.

Sinitic examples

The following are examples of A-not-A questions in languages belonging to the Sinitic linguistic family.

In Mandarin

In forming A-not-A questions, A must remain the same on both sides. A is essentially a variable which can be replaced with a grammatical particle such as a modal, adverb, adjective, verb, or preposition.

Patterns

In Mandarin, there are 6 attested patterns of A-not-A: A-not-A, AB-not-AB, A-not-AB, AB-not-A, a-not-A, and a-not-AB of which "A" stands for the full form of the predicate, "B" stands for the complement, and "a" stands for the first syllable of a disyllabic predicate.[9]

A-not-A form

Example (3) illustrates that A-not-A pattern, where A is the verb qu 'go', and qu bu qu is 'go not go'.

(3) 你 去 不 去?

ni qu bu qu

you go not go

Are you going?

AB-not-AB form

Example (4) illustrates the AB-not-AB pattern, where AB is the constituent consisting of the verb rende, 'know', as A, and the complement zhe ge ren, 'this CL man', as B, combining to form the AB constituent rende zhe ge ren 'know this CL man'. This produces rende zhe ge bu rende zhe ge ren, 'know this CL man not know this CL man.'

(4) 你 認得 這 個 人 不 認得 這 個 人 ?

ni rende zhe ge ren bu rende zhe ge ren

you know this CL man not know this CL man

Do you know this man?

A-not-AB form

Example (5) illustrates the A-not-AB pattern, where A is the verb rende, 'know', AB is the constituent consisting of the A verb rende, 'know', and the complement zhe ge ren, 'this CL man', as B, combining to form the AB constituent rende zhe ge ren 'know this CL man'. This produces rende bu rende zhe ge ren, 'know not know this CL man'.

(5) 你 認得 不 認得 這 個 人 ?

ni rende bu rende zhe ge ren

you know not know this CL man

Do you know this man?

AB-not-A form

Example (6) illustrates the AB-not-A pattern, where AB is the constituent rende zhe ge ren, 'know this CL man' consisting of rende, 'know' as A and zhe ge ren, 'this CL man as B; A is likewise rende, 'know', in the second part of the construction. This produces rende zhe ge ren bu rende, 'know this CL man not know'.

(6) 你 認得 這 個 人 不 認得 ?

ni rende zhe ge ren bu rende

you know this CL man not know

Do you know this man?

a-not-A form

Example (7) illustrates the a-not-A pattern, where a is the first syllable, fang, of the disyllabic predicate fangbian, 'convenient', and A is the full predicate fangbian, and fang-bu-fangbian is 'con(venient)-not convenient'.

(7) 不 知道 你 方 不 方便?

bu zhidao ni fang-bu fangbian

not know you con(venient)-not convenient

Is that all right with you?

a-not-AB form

Example (8) illustrates the a-not-AB pattern, where a is the first syllable, he, of the disyllabic predicate heshi, 'suitable', and AB is the constituent consisting of heshi, 'suitable' as A and jiao quan, 'teaching fist' as B, combining to form the AB constituent heshi jia quan, 'suitable teaching fist'. This produces he-bu heshi jian quan, 'suit(able)-not suitable teaching fist'.

(8) 你 看 這裡 合不 合適 教 拳?

ni kan zheli he-bu heshi jiao quan

you see here suit(able)-not suitable teaching fist

Is this suitable for your martial club?

Grammatical particles used to form A-not-A questions

A-not-A can be formed by a verb, an adjective, or an adverb,[11] as well as modals.[1]

Verb

In the interrogative clause, A-not-A occurs by repeating the first part in the verbal group (with the option of an auxiliary) and the negative form of the particle is placed in between. However, this clause does not apply when using perfective in aspect. Instead, 沒有; meiyou is used to replace the repeated verb used in A-not-A form.[12]

- V-NEG-V type:[1]

Here, the verb qu, 'go', is A, and there is no object.

(9.a) 你去不去? A: 去/不去

ni qu bu qu? qu/bu qu

you go not go go/not go

DP V-NEG-V V/NEG V

Are you going? Yes/No

- V-NEG-V-Object type:[1]

Here the verb kan, 'watch', is again A, and while there is an object, the object is not included in "A", and is therefore not reduplicated.

(9.b) 你看不看电影? A: 看/不看

ni kan bu kan dianying? kan/bu kan

you watch not watch movie watch/not watch

N V-NEG-V-N V/NEG V

Will you watch the movie? Yes/No.

- V-Object-NEG type:[1]

Here, the verb kan, 'watch', is likewise A, and while the object is included before NEG, it is not included in A, and is therefore not reduplicated, although it remains an option.

(9.c) 你看电影不? A: 看/不看

ni kan dianying bu? kan/bu kan

you watch movie not watch/not watch

N V-DP-NEG V/NEG V

Will you watch the movie? Yes/No

- V-Object-NEG-V type[1](debatable):

Here, the verb kan, 'watch', is also used for A, and while the object is included before NEG, it is not included in A, and is therefore not reduplicated. A is reduplicated here.

(9.d) 你看电影不看? A: 看/不看

ni kan dianying bu kan? kan/bu kan

you watch movie not watch watch/not watch

DP V-DP-NEG-V V/NEG V

Will you watch the movie? Yes/No

- Answers to (9.a), (9.b), (9.c), and (9.d) must be in the form "V" or "not-V"

There is some debate among speakers as to whether or not 3.d. is grammatical, and Gasde argues that it is.

Adjective or adverb

- A-NEG-A type:[1]

Here, the adjective hao, 'good', is A, and it is reduplicated. The word ben is a classifier, which means it is a counter word for the noun 'book'.

(10.a) 这本书好不好? A: 好/不好

zhe ben shu hao bu hao? hao/bu hao

this CL book good not good good/not good

DP A-NEG-A A/NEG A

Is this book good? Yes/No

- A-NEG type:[1]

Here, the adjective hao, 'good', is A, but it is not reduplicated.

(10.b) 这本书好不? A: 好/不好

zhe ben shu hao bu? hao/bu hao

this CL book good not good/not good

DP A-NEG A/NEG A

Is this book good? Yes/No

- Answers to (10.a), (10.b) must be in the form A or not-A.

Preposition

- P-NEG-P type:[13]

Here, the preposition zai, 'at', is A, and it is reduplicated.

(11.a) 张三在不在图书馆? A: 在/不在

Zhangsan zai bu zai tushuguan? zai/bu zai

Zhangsan at not at library at/not at

DP P-NEG-P DP P/NEG P

Is Zhangsan at the library? Yes/No

- P-NEG-P type:[13]

Here, the preposition zai, 'at', is A, and it is not reduplicated.

(11.b) 张三在图书馆不? A: 在/不在

Zhangsan zai tushuguan bu? zai/bu zai

Zhangsan at library not at/not at

DP P-DP-NEG P/NEG P

Is Zhangsan at the library? Yes/No

- Answers to (11.a) and (11.b) must be in the form P or not-P.

Modal

- M-NEG-M-V-Object type:[1]

Here, the modal dare is A and it is reduplicated.

(12.a) 你敢不敢杀鸡? A: 敢/不敢

ni gan bu gan sha ji? gan/bu gan

you dare not dare kill chicken dare/not dare

N M-NEG-M -V -DP M/NEG M

Do you dare kill chicken? Yes/No

- The answer to (12.a) must be in the form M or not-M.

A-not-A questions in Cantonese

Despite having the same negative marker as Mandarin, "不" bat1 is only used in fixed expressions or to give literacy quality,[14] and only "唔" m4 is used as a negative marker in A-not-A questions.[9]

One distinction in Cantonese when compared to Mandarin is that certain forms of A-not-A questions are not attested due to dialectal differences.[2]

A-not-A form

Like its Mandarin counterpart, this form is attested in Cantonese as shown by the sentence pair in (13),[9] where in example (13.a), A is the verb lai, 'come', and lai m lai is 'come not come', and in (13.b), A is the verb lai, 'come', and lai bu lai is 'come not come'.

(13.a) 佢哋 嚟 唔 嚟 ?

keoidei lai m lai?

they come not come

Are they coming?

(13.b) 他們 來 不 來?

tamen lai bu lai?

they come not come

Are they coming?

AB-not-AB form

As shown by (14.a), this is not an attested form in Cantonese, unlike the counterpart in Mandarin in (14.b).[2]

Here in (14.a) A is the verb zungji, 'like', and B the noun jamok, 'music', producing the AB form zungji jamok, 'like music'. This would produce the ungrammatical structure zungji jamok m zungji jamok, 'like music not like', which is a poorly-formed sentence in Cantonese.

In the well-formed sentence shown below in (14.b), A is the verb xihuan, 'like', and B is the noun yinyue, 'music', producing the AB form xihuan yinyue, 'like music'. This produces xihuant yinyue bu xihuan yinue, 'like music not like music', a grammatical sentence in Mandarin.

(14.a) ??/*你 鐘意 音樂 唔 鐘意 音樂?

??/*nei zungji jamok m zungji jamok?

??/*you like music not like music

Do you like music?

(14.b) 你 喜歡 音樂 不 喜歡 音樂?

ni xihuan yinyue bu xihuan yinyue?

you like music not like music

Do you like music?

A-not-AB form

This form is only attested in Cantonese if the predicate is a monosyllabic word as shown by (15.a), where A is the verb faan, 'return', and AB is the constituent faan ukkei, 'return home'. This can be compared to the Mandarin counterpart in (15.b) where A is the verb hui, 'return', and AB is the constituent hui jia, 'return home.[9]

(15.a) 你 返 唔 返 屋企?

nei faan m faan ukkei?

you return not return home

Are you going home?

(15.b) 你 回 不 回 家?

ni hui bu hui jia?

you return not return home

Are you going home?

A-not-AB is not attested in Cantonese if the predicate is a bi-syllabic word as shown by (16.a), where A would be the verb zungji, 'like', and AB would be the constituent zungji jamok, 'like music'. This contrasts with its Mandarin counterpart in (16.b), where A is the verb xihuan, 'like', and B is the complement yinyuee, music', combining into the AB form xihuan yinyue, 'like music'.[2] In such cases, Cantonese speakers usually use the form a-not-AB, like (8).[9]

(16.a) ??/*你 鐘意唔鐘意 音樂?

??/*nei zungji-m-zungji jamok?

??/*you like-not-like music

Do you like music?

(16.b) 你 喜歡不喜歡 音樂?

ni xihuan-bu-xihuan yinyue?

you like-not-like music

Do you like music?

AB-not-A form

This form is only attested in Cantonese if the predicate is a monosyllabic word A, exemplified in (17.a) with the verb faan, 'return', with an object B, exemplified in (17.a) with the noun ukkei, 'home'. (17.a) is shown below with its Mandarin counterpart in (17.b), where A is the verb hui, 'return', and B is the noun jia, 'home'.[9]

(17.a) ?你 返 屋企 唔 返?

?nei faan ukkei m faan?

you return home not return

Are you going home?

(17.b) 你 回 家 不 回?

ni hui jia bu hui?

you return home not return

Are you going home?

Note that such forms of AB-not-A in monosyllabic words are used by older generations.[15]

When the predicate is a bi-syllabic word, then AB-not-A form is not attested as shown in (18.a), unlike its Mandarin counterpart in (18.b).[9]

(18.a) *你 鐘意 佢 唔 鐘意?

*nei zungji keoi m zungji?

you like she not like

Do you like her?

(18.b) 你 喜歡 她 不 喜歡 ?

ni xihuan ta bu xihuan?

you like she not like

Do you like her?

In Amoy

Amoy exhibits A-not-A forms, and differs from Mandarin and Cantonese in its frequent use of modals or auxiliaries in forming these constructions. Amoy forms also differ in that the morphemes for A do not match each other in a given sentence. In these constructions one of the morphemes may also be deleted, as can be seen in Examples (27), (28), and (29), though when this happens it may only be deleted from the negative predicate.

Negative markers in Amoy

The following negative markers are used.[16] Alternate transliterations are shown in bold.

(19) a. m negative of volition (m-1)

b. m negative simplex (m-2)

c. bo negative possessive/existential/affirmative aspect

bou

d. bue negative potential/possibility

e. be negative perfective aspect

While m-1 occurs as a free morpheme with its own semantic feature indicating volition, m-2 is cannot function by itself as a verb and works only to express negation. It is attested only with a limited amount of verbs.

A-not-A constructions

Shown below are A-not-A constructions in Amoy.[17]

With auxiliaries that can be used as main verbs

The following is a list of A-not-A constructions in Amoy with auxiliary verbs which may function as the main verb of a sentence.

U — bou: 'have — not have'

The auxiliary verb u here functions as an aspectual marker indicating that an action has been completed. In u — bou A-not-A constructions, u functions as the first A, corresponding with the auxiliary 'have', while bou functions as the second A of the A-not-A construction, corresponding with the negative counterpart 'not have'. Example (20) illustrates the use of this construction.

(20) li u k'ua hi bou?

you have see movie not have

Did you see the movie?

Bat — m bat: 'to have experienced — not to have experienced'

The auxiliary verb bat functions as an aspectual marker indicating experience. In bat — m bat A-not-A constructions, bat functions as the first A, corresponding with an auxiliary expressing the sense of 'to have experienced', while m bat functions as the second A of the A-not-A constructions, corresponding with the negative counterpart 'not to have experienced'. Example (21) illustrates the use of this construction.

(21) li bat sie p'ue ho i a m bat

you have-ever write letter give him or not have-ever

Have you ever written to him?

Si — m si: 'to be — not to be'

The auxiliary verb si works to express emphasis. In si — m si constructions A-not-A constructions, si functions as the first A, roughly corresponding with 'to be', and m si as the second A, indicating the negative counterpart 'not to be'. Example (22) illustrates the use of this construction.

(22) i si tiouq k'i Tai-pak a m si

he be must go Taipei or not be

Does he really have to go to Taipei?

With auxiliaries that cannot be used as main verbs

The following is a list of A-not-A constructions in Amoy with auxiliary verbs which may never be used as the main verb of a sentence.

Beq — m: 'to want to — not to want to'

The use of a beq — m construction is used to express an intention or an expectation. In these constructions, beq functions as the first A, indicating 'to want to', and m as the second A, here working with beq to express its negative counterpart 'not want to.' Example (23) illustrates the use of this construction.

(23) li beq tsiaq hun a m

you want eat cigarette or not

Do you want to smoke?

Tiouq — m bian: 'must — must not'

The use of a tiouq — m bian construction expresses a sense of obligation. In these constructions, tiouq functions as the first A, indicating 'must', and m bian as the second A, here indicating the negative counterpart 'must not'. Example (24) illustrates the use of this construction.

(24) li tiouq k'i ouq-tng a m bian

you must go school or not must

Do you have to go to school?

T'ang — m t'ang: 'may — may not'

The use of a t'ang — m t'ang construction expresses a sense of permission. In these constructions, t'ang functions as the first A, indicting 'may', and m t'ang as the second A, here indicating the negative counterpart 'may not'. Example (25) illustrates the use of this construction.

(25) gua t'ang ts'ut k'i a m t'ang

I may out go or not may

May I go out?

E — bue: 'could — could not'

The use of an e — bue construction expresses a sense of possibility or probability. In these constructions, e functions as the first A, indicating 'could', and bue as the second A, here indicating the negative counterpart 'could not'. Example (26) illustrates the use of this construction.

(26) li e k'i Tai-uan a bue

you could go Taiwan or not could

Will you be going to Taiwan?

E tang — bue tang: 'can, ability to do something — can't, inability to do something'

The use of an e tang — bue tang construction expresses a sense of the ability to do something. In these constructions, e tang functions as the first A, indicating 'can', and bue tang as the second A, here indicating the negative counterpart 'can't'. Example (27) illustrates the use of this construction as well as an instance of deletion from the negative predicate.

(27) bin-ã-tsai li e tang lai a bue

tomorrow you can come or not

Can you come tomorrow?

E sai — bue sai: 'could, can manage to or might — couldn't, couldn't manage or might not'

The use of an e sai — bue sai construction expresses a sense of a potential ability to do something. In these constructions, e sai functions as the first A, indicating 'could', and bue sai as the second A, here indicating the counterpart 'couldn't'. Example (28) illustrates the use of this construction as well as an instance of deletion from the negative predicate.

(28) li e sai ka gua kia p'ue a bue

you could for I mail letter or not

Could you mail a letter for me?

E hiau — bue hiau: 'to know how/be knowledgeable about — not to know how/be knowledgeable about'

The use of an e hiau — bue hiau construction expresses a sense of one's knowledge. In these constructions, e hiau functions as the first A, indicating 'to know how', and bue hiau as the second A, here indicating the negative counterpart 'not to know how'. Example (29) illustrates the use of this construction as well as an instance of deletion from the negative predicate.

(29) li e hiau kong Ing-bun a bue

you know speak English or not

Do you know how to speak English?

In Korean

The following are examples of A-not-A questions in Korean.[18]

There are three salient morphological varieties of A-not-A question in Korean.[18] Like all A-not-A questions, the questions can be answered with an affirmative, 네, ney, or negative 아니요, anyo.

Pre-predicate negation

Both an and mos can precede the predicate in A-not-A questions.

An

Example (26) illustrates the use of an, short form for ani-, which expresses simple negation. Here A is ca-ni, 'sleep-COMP', and ca-ni an ca-ni is 'sleep-COMP not sleep-COMP'.

(26) Q: 지우-는 자-니 안 자-니? A: 자-요 /안 자-요

ciwu-nun ca-ni an ca-ni? ca-yo /an ca-yo

Jiwoo-TOP sleep-COMP not sleep-COMP sleep-HON/not sleep-HON

Is Jiwoo sleeping or not? (She) is sleeping/(She) isn't sleeping

Mos

Example (27) illustrates the use of mos, which expresses impossibility or inability. Here A is ka-ss-ni, 'go-PAST-COMP' and ka-ss-ni mos ka-ss-ni is 'go-PAST-COMP cannot go-PAST-COMP'.

(27) Q: 민수 -는 학교 -에 갔-니 안 갔-니?

Minsoo-nun hakkuo-ey ka-ss-ni mos ka-ss-ni?

Minsoo-TOP School-LOC go-PAST-COMP cannot go-PAST-COMP

Could Minsooo go to school or not?

Inherently-negative predicate

Korean has three negative predicates that can form A-not-A question, molu-, eps-, and ani-.

Molu-

Example (28) illustrates the use of molu-, which means 'don't know'.

(28) 너-는 저 학생-을 아-니 모르-니?

ne-nun ce haksayng-ul a-ni molu-ni?

you-TOP that student-ACC know-COMP not.know-COMP

Do you know that student or not?

Eps-

Example (29) illustrates the use of esp-, which means 'do not have; do not exist'.

(29) 지우-는 집-에 있니 없니?

ciwu-nun cip-e iss-ni esp-ni?

Jiwoo-TOP home-LOC be-COMP not.be-COMP

Is Jiwoo at home or not?

Ani-

Example (30) illustrates the use of ani-, which means 'is not'.

(30) 이게 네 책-이-니 아니-니

ike ne chayk-i-ni ani-ni?

this you book-be-COMP not.be-COMP

IS this your book or not?

Mal

Meaning 'desist from', mal follows an affirmative polar question, and will occur instead of a reduplicated full verb that has a post predicate negation, meaning that there is only one full verb in this type of A-not-A question.

(31) 우리-는 잘-까 말-까?

wili-nun ca-l-kka mal-kka?

we-TOP sleep-MOOD-COMP not.MOOD-COMP

Should or shouldn't we go to bed?

However, the modal auxiliary verb mal is restricted in that it does not co-occur in predicative adjectives or the factual complementizer ni. Moreover, with mal being a bound form, it cannot be the echo negative answer. Instead, the full negative verb will be provided as the answer, taking an negation, as illustrated in (32).

(32) 너-는 콘서트-에 갈-래 말-래? A: *말-래 안 갈-래

ne-nun khonsethu-ey ka-l-ay mal-lay? *mal-lay / an ka-l-ay

you-TOP concert-LOC go-MOOD-COMP not.MOOD-COMP not-MOOD-COMP / not go-MOOd-COMP

Are (you) going to the concert or not? (I) am not going

Analysis: The post-syntactic approach

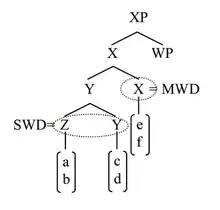

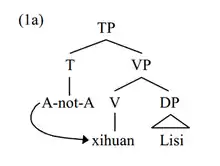

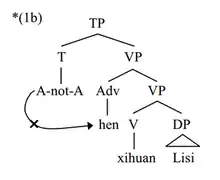

One analysis of the formation of the A-not-A construction is the post-syntactic approach, through two stages of M-merger. First, the A-not-A operator targets the morphosyntactic word (MWd) which is the head that is closest to it and undergoes lowering. Then, reduplication occurs to yield the surface form of the A-not-A question.[13]

Tseng suggests that A-not-A occurs post-syntactically, at the morphological level. It is movement that occurs overtly at the phonetic form, after the syntactic movement has occurred. A-not-A is a feature of T that operates on the closest, c-commanded MWd, and not subwords (SWd). The elements that undergo post-syntactic movement are MWds. A node X is a MWd iff X is the highest segment and X is not contained in another X. A node X is a SWd if X is a terminal node and not an MWd.[13] The A-not-A operation is a MWd to MWd movement.

A-not-A operator lowering

The A-not-A operator is defined as an MWd. The A-not-A operator can only lower to a MWd which is immediately dominated by the maximal projection that is also immediately dominated by the maximal projection of the A-not-A operator. An SWd cannot be the target for the A-not-A operator. In addition, if there is an intervening MWd or SWd between the A-not-A operator and its target, the A-not-A operation fails.[13]

A-not-A operator lowering must satisfy four conditions:

- The A-not-A operator targets the closest MWd that is the X′-theoretic head that it c-commands.

- Closeness of the head is qualified by: (i) The closest head is a X′-theoretic head of the maximal which is immediately dominated by the maximal projection of the A-not-A operator. (ii) The target must have overt phonological realization.

- There is not any non-X′-theoretic head or SWd intervening between the A-not-A operator and its target.

- Intervention is defined by c-command relation.

After lowering, the A-not-A operator triggers reduplication on the target node. The reduplication domain can be the first syllable of the targeted element, the targeted element itself, and the maximal projection that contains the targeted element. Reduplication is linear and the A-not-A operator cannot skip the adjacent constituent to copy the next constituent.[13]

Reduplication of first syllable of adjacent morphosyntactic word

In first syllable reduplication, the A-not-A operator copies the first syllable of the adjacent MWd and moves the reduplicant, i.e. copied syllable, to the left of the base MWd. Then the negation is inserted between the reduplicant and base to form a grammatical sentence. In (33.a), the A-not-A operator copies the first syllable tao of the MWd taoyan. The reduplicant tao is put at the left of the base taoyan and then the negative constituent bu is inserted in between. In figure (33.b) *Zhangsan taoyan Lisi-bu-tao is ungrammatical because tao cannot be put to the right of the maximal projection VP, taoyan Lisi.

(33.a) 张三 讨不讨厌 李四

Zhangsan tao-bu-taoyan Lisi

Zhangsan hate-not-hate Lisi

Does Zhangsan hate Lisi or not?[13]

(33.b)*张三 讨厌 李四不讨

*Zhangsan taoyan Lisi-bu-tao

Zhangsan hate Lisi-not-hate[13]

Reduplication of adjacent morphosyntactic word

In MWd reduplication, the A-not-A operator copies the adjacent MWd and moves the reduplicant MWd overtly to the left of the base MWd or to right of the base maximal projection containing the MWd. Otherwise, the reduplicant can move covertly, i.e. in such a way that there is no overt surface evidence, to the right of the base maximal projection containing the MWd. The negation is then inserted between the reduplicant and base to form a grammatical sentence. In (34.a) the A-not-A operator copies the MWd taoyan. The reduplicant taoyan is overtly put at the left of the base taoyan and then the negative constituent bu is inserted in between. In (34.b) the A-not-A operator copies the MWd taoyan. The reduplicant taoyan is overtly put at the right of the base taoyan Lisi and then the negative constituent bu is inserted in between. In (34.c) the A-not-A operator copies the MWd taoyan. The reduplicant taoyan is covertly put at the right of the base taoyan Lisi after which the negative constituent bu is inserted.

(34.a) 张三 讨厌不讨厌 李斯

Zhangsan taoyan-bu-taoyan Lisi

Zhangsan hate-not-hate Lisi

Does Zhangsan hate Lisi or not?[13]

(34.b) 张三 讨厌 李斯 不 讨厌

Zhangsan taoyan Lisi bu taoyan

Zhangsan hate Lisi not hate

Does Zhangsan hate Lisi or not?[13]

(34.c) 张三 讨厌 李斯 不 (讨厌)

Zhangsan taoyan Lisi bu (taoyan)

Zhangsan hate Lisi not (hate)

Does Zhangsan hate Lisi or not?[13]

Reduplication of the maximal projection containing adjacent morphosyntactic word

In maximal projection reduplication, the A-not-A operator copies the maximal projection that contains the adjacent MWd and moves the reduplicant either to the left or to the right of the base. The base may be just the MWd or the maximal projection containing the MWd. The maximal projection may be any XP (VP, AP, PP etc.). The negation is then inserted between the reduplicant and base to form a grammatical sentence. In (35) the A-not-A operator copies the maximal projection VP taoyan Lisi. The reduplicant taoyan Lisi is put at the left of the base taoyan Lisi and then the negative constituent bu is inserted in between.

(35) 张三 讨厌 李斯 不 讨厌 李斯

Zhangsan taoyan Lisi bu taoyan Lisi

Zhangsan hate Lisi not hate Lisi

Does Zhangsan hate Lisi or not?[13]

References

- Gasde, Horst-Dieter (25 January 2004). "Yes/no questions and A-not-A questions in Chinese revisited". Linguistics. 42 (2): 293–326. doi:10.1515/ling.2004.010.

- Law, Ann (2001) A-not-A questions in Cantonese. UCLWPL 13, 295-318.

- Zhu, Dexi (1985). "Hanyu Fangyan de Liang-Zhong Fanfu Wenju. (Two Kinds of A-not-A Questions in Chinese Dialects.)". Zhingguo Yuwen: 10–20.

- Hagstrom, Paul (2006). "Chapter 7 Hagstrom: A-no-A Question". The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 173–213.

- Matthew S. Dryer. 2013. Position of Polar Question Particles. In: Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.) The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- Han, Chung-Hye; Romero, Maribel (August 2004). "The Syntax of Whether/Q... or Questions: Ellipsis Combined with Movement" (PDF). Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. 22 (3): 527–564. doi:10.1023/b:nala.0000027674.87552.71.

- HUANG, C. T. JAMES (1982). "Move Wh in a Language Without Wh Movement". The Linguistic Review. 1 (4). doi:10.1515/tlir.1982.1.4.369. ISSN 0167-6318.

- Huang, C.-T. James (1991), "Modularity and Chinese A-not-A Questions", Interdisciplinary Approaches to Language, Springer Netherlands, pp. 305–332, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-3818-5_16, ISBN 9789401056977

- Clare, Li (2017). The syntactic and pragmatic properties of a-not-a question in Chinese (Thesis). hdl:10092/13628.

- Lü (1985). "疑文 否定 肯定 Yiwen, Fouding, Kending (Questioning, Negation, Affirmation)". 中國語文 Zhongguo Yuwen. 4: 241–250.

- Chen, Y.; Weiyun He, A. (2001). "Dui bu dui as a pragmatic marker: Evidence from chinese classroom discourse". Journal of Pragmatics. 33 (9): 1441–1465. doi:10.1016/S0378-2166(00)00084-9.

- Li, Eden Sam-hung (2007). "Enacting Relationships: Clause as Exchange". Systemic Functional Grammar of Chinese. A&C Black. pp. 116–197. ISBN 9781441127495.

- Tseng, W. H. K., & Lin, T. H. J. (2009). A Post-Syntactic Approach to the A-not-A Questions. UST Working Papers in Linguistics, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, 107-139.

- Matthews, Stephen; Yip, Virginia (2011). Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar. London and New York: Routledge. p. 283. ISBN 978-0415471312.

- Shao, J. -M (2010). 漢語方疑問範疇比較研究 Hanyu fangyan yiwen fanchou bijiao yanjiu [Comparative Study of Chinese Dialect Interrogative Question Category]. Guangzhou: Jinan Daxue Database.

- Crosland, Jeff (1998). "Yes-No Question Patterns in Southern Min: Variation across Some Dialects in Fujian". Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 7 (4): 257–285. doi:10.1023/A:1008351807694. ISSN 0925-8558. JSTOR 20100747.

- Teoh, Irene (January 1967). "Auxiliary Verbs and the A-Not-A Question in Amoy". Monumenta Serica. 26 (1): 295–304. doi:10.1080/02549948.1967.11744971. ISSN 0254-9948.

- Ceong, Hailey Hyekyeong (2011). The Syntax of Korean Polar Alternative Questions: A-not-A (Thesis).