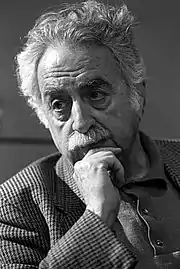

Abraham Serfaty

Abraham Serfaty (Arabic: أبراهام سرفاتي; January 16, 1926 – 18 November 2010) was an internationally prominent Moroccan dissident, militant, and political activist, who was imprisoned for years by King Hassan II of Morocco, for his political actions in favor of democracy , during the Years of Lead. He paid a high price for such actions: fifteen months living underground, seventeen years of imprisonment and eight years of exile. He returned to Morocco in September 1999.

Abraham Serfaty | |

|---|---|

أبراهام السرفاتي | |

|

Life and politics

Abraham Serfaty was born in Casablanca, on January 16, 1926, to a middle-class Sephardi liberal humanistic Jewish family originally from Tangier .[1] He graduated in 1949 of École des Mines de Paris one of the most prominent French engineering Grandes écoles. His path as a political activist started very early: in February 1944, he joined the Moroccan Youth Communists,[1] and, upon his arrival in France in 1945, the French Communist Party. When he returned to Morocco in 1949, he joined the Moroccan Communist Party. His anti-colonialist fight had him arrested and jailed by the French authorities, and in 1950 he was assigned a forced residence in France for six years.

On the morrow of Morocco's independence, he encumbered several, more technical than political, posts and was part of the Ministry of Economy from 1957 to 1960. During that time, he has been one of the many promoters of the new mining policy of the newly independent Morocco. From 1960 to 1968, he was the director of the Research-Development of the Cherifian Office of Phosphates, but revoked of his duties because of his solidarity with miners at one strike. From 1968 to 1972, he taught at the Engineers School of Mohammedia, and at the same time, collaborated at the "Souffles/Anfas" artistic journal, headed by Abdellatif Laabi.

Abraham Serfaty was a Moroccan Jew, but also an anti-Zionist Jew who did not recognize the State of Israel and was outraged by what he saw as the mistreatment of the Palestinians.

In 1970, Serfaty left the Communist Party, which he considered to be too doctrinarian and became deeply involved in the establishment of a Marxist-Leninist left-wing organization called "Ila al-Amam" (En Avant in French, Forward in English). In January 1972, he was arrested for the first time and savagely tortured, but released after heavy popular pressure. As he was again targeted for his continuing fight, Serfaty went underground in March 1972, with one of his friends Abdellatif Zeroual, who was also wanted by the authorities. It was then that he met for the first time Christine Daure, a French teacher who then helped both men to hide.

After several months of hiding, Abraham Serfaty and Abdellatif Zeroual were arrested again in 1974. After their arrest, Abdellatif Zeroual died, a victim of torture. In October 1974, at "Derb Moulay Chérif", center of "interrogation" = (torture) in Casablanca, Abraham Serfaty was one of the five culprits sentenced to life in prison. He was officially charged with "plotting against the State's security", but the heavy sentence seemed to have been more a result for his attitude against the annexing of the Western Sahara, even if this motif did not appear in the official indictment, than his political activism. He then served seventeen years at the Kenitra prison, where, thanks to Danielle Mitterrand's help, he was able to marry his biggest supporter, Christine Daure.

Exile and return

International pressure was enough in Serfaty's favor that he was finally released from prison in September 1991, but immediately banished from Morocco and deprived of his Moroccan nationality on grounds that his father was Brazilian. He found a haven in France, with his wife, Christine Daure-Serfaty. From 1992 to 1995, Serfaty taught at the University of Paris-VIII, in the department of political sciences, on the theme of "identities and democracy in the Arab world".

Eight years after his exile and two months after the death of King Hassan II, he was finally allowed by the new king to return to Morocco in September 1999, and had his Moroccan passport restored to him. He then settled at Mohammedia with his wife Christine in a house made available to them and even received a monthly stipend. In the same year, he was appointed Advisor to the National Moroccan Office of Research and Oil Exploitation (Onarep). This nomination did not stop him for asking, in December 2000, the then Moroccan Prime Minister Abderrahmane Youssoufi to resign after the attacks on the independent newspapers and magazines and restrictions of their rights and freedom of speech. Serfaty died in Marrakech, Morocco in November 2010.

Abraham Serfaty was a fervent anti-Zionist, to the extent that he declared that Zionism had nothing to do with Judaism. He moreover stated that the Jews had no right to Palestine, especially Jerusalem and the Western Wall. He stated that it was all lies to make them part of Judaism. He led several demonstrations supporting the Palestinian people, especially during Israeli air raids on Gaza, stating that Jerusalem was the capital of Palestine and that the Jews, especially Israeli Jews, were liars, criminals, and had no right to it. He lived, upon his return to Morocco from exile isolated and avoided by the rest of the Jewish Moroccan community. Only two official representatives of the Moroccan Jewish community were present at his burial. His funeral at the Jewish cemetery in Rabat was solely attended by Moroccan Muslims, on account of his political stance regarding the Palestinian issue.

Abraham Serfaty, like other Sephardim, by example Ilan Halevi or Henri Curiel wanted to be anti-Zionist. In Prison Writings on Palestine, he writes “Zionism is above all a racist ideology. She is the Jewish reverse of Hitlerism [...]It proclaims the State of Israel "a Jewish state above all," just as Hitler proclaimed an Aryan Germany. » [2]

Abraham Serfaty was the co-author, with his wife Christine, of the book The Other's Memory (La Mémoire de l'Autre), published in 1993.

Death

Abraham Serfaty died on November 18, 2010, at the age of 84 in a clinic in Marrakech.[3]

Awards and honors

See also

References

- Childs, Martin (3 December 2010). "Abraham Serfaty: Political activist who fell foul of the French colonial authorities as well as Morocco's authoritarian King Hassan II". The Independent. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- Ecrits de prison sur la Palestine

- Marco : mort d’Abraham Serfaty, célèbre opposant à Hassan II

- "The unsubdued, Jews, Moroccans and Rebels" (L'Insoumis, Juifs, marocains et rebelles), with Mikhaël Elbaz, Éditions Desclée de Brouwer, 2001, ISBN 2-220-04724-5

- "Morocco, from black to grey" (Le Maroc du noir au gris), Éditions Syllepse, 1998, ISBN 2-907993-89-5

- "The Other's Memory (La Mémoire de l'Autre), Éditions Stock, 1993, ISBN 9954-419-00-4

- "In the King's Jails – Kenitra's writings on Morocco" (Dans les Prisons du Roi – Écrits de Kénitra sur le Maroc), Editions Messidor, Paris, 1992, ISBN 2-209-06640-9

- "From jail, writings on Palestine" (Écrits de prison sur la Palestine), Éditions Arcantère, 1992, ISBN 2-86829-059-0

- "The anti-zionist struggle and the Arab Revolution (Essay on Moroccan Judaism and Zionism)" (Lutte anti-sioniste et Révolution Arabe – Essai sur le judaïsme marocain et le sionisme), Éditions Quatre-Vents, 1977, ISBN