Acacia acuminata

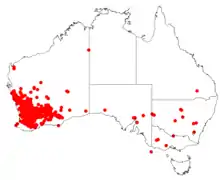

Acacia acuminata, known as mangart and jam, is a tree in the family Fabaceae. Endemic to Western Australia, it occurs throughout the south west of the State. It is common in the Wheatbelt, and also extends into the semi-arid interior.

| jam tree | |

|---|---|

| |

| mature tree in native habitat, circa 1920 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Clade: | Mimosoideae |

| Genus: | Acacia |

| Species: | A. acuminata |

| Binomial name | |

| Acacia acuminata | |

| |

| Occurrence data from AVH | |

Description

Acacia acuminata grows as a tall shrub or small tree growing 3-7m, In ideal conditions it may grow to a height of ten metres, but in most of its distribution it does not grow above five metres. As with most Acacia species, it has phyllodes rather than true leaves. These are bright green, around ten centimetres long and about two millimetres wide, and finish in a long point. The lemon yellow flowers are held in tight cylindrical clusters about two centimetres long, flowering occur late winter to spring. The pods are light brown and flattened, about ten centimetres long and five millimetres wide and are present during summer.

The nutritional composition of the numerous seeds, a shiny brown-black colour, is 45% protein, 28% fats and 15% carbohydrates.[1]

Taxonomy

A species currently allied to clade Mimosoideae. Acacia acuminata was first described by George Bentham as family Mimosaceae in 1842, based on a collection made by James Drummond and forwarded to England.[1]

There are no currently recognised subspecies. The taxon previously called Acacia acuminata subsp. burkittii (Benth.) Kodela & Tindale[2] is now considered to be a separate species and is called Acacia burkittii (Benth.)[3]

Three variations of A. acuminata are currently recognized:[4]

A. acuminata (small seed variant)

A. acuminata (narrow phyllode variant)

A. acuminata (broad phyllode variant / typical variant)

The species name acuminata comes from the Latin acuminatus, which means pointed or elongated. This refers to the long tapering point at the end of each phyllode. The common name raspberry jam tree refers to the strong odour of the freshly cut wood, which resembles raspberry jam, and is referred to as fine leaf jam, "raspberry jam" or jam tree. The Noongar peoples know the tree as Manjart, Munertor, Mungaitch or Mungat.[5]

Cultivation

Acacia acuminata has high frost tolerance and medium salt tolerance. Acacia acuminata is tolerant of drought and frosts and is moderately salt tolerant. It requires at least 250mm/year (9.8in./year) average rainfall.[6] Grows on seasonally dry duplex soils. Coppicing ability is absent or very low and it may be killed by fire. The wood has a distinct scent of raspberry jam and is very durable in the ground and favored for round fencing material; it has an attractive grain and is used for craft wood. A. acuminata comprises a number of informal variants (see above) and is the main host being used in Sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) plantations.[7]

Distribution and habitat

Widely distributed throughout the Southwest of Australia and recorded into the Eremaean province.[3] The explorer Henry Lefroy found the species was very common between Narembeen and the Avon River and growing with sandalwood (Santalum acuminatum) in 1863, the conservator of forests, John Ednie Brown, estimated in 1895 that an area of four million acres was dominated by this species growing with Eucalyptus loxophleba (York gum), the valuable sandalwood having already been cleared. Drummond noticed the species growing outside its range at Guildford, attributing this occurrence to spilled seed that had been transported to the site in food bags. The first thorough survey of the distribution was documented by Surveyor General Malcolm Fraser in 1882, who recorded a range from Champion Bay to the south at Gordon River; he also notes the consumption of its seed and regrowth by introduced stock animals.[1]

Uses

The wood is hard and durable, attractive, reddish, and closely grained. It has been used extensively for fence posts,[8] for ornamental articles, and for high-load applications such as sheave blocks. The wood's "air dried" density is 1040 kg/m3.[9] The tensile strength is around eighty megapascal, the transverse strength is over one hundred MPa.[10] It is also being used as a companion/host tree with sandalwood (Santalum spicatum) plantations in the Wheatbelt region.[11] The extensive use of the plant for wood, food and medicine by Nyungar peoples saw it regarded as a valuable resource. The abundance of seed was made into flour. The sap was collected and administered as medicine, either immediately or prepared and stored for later use. The wood was preferred in the manufacture of kylies, a boomerang-type weapon.[1]

The timber's resistance to termites was exploited for fence-posts when European agriculture was expanded into nearby areas, the durability of these is evident in fencing over 100 years old.[1] The conservator of state forests, Charles Lane-Poole, noted the longevity of fence posts in the 1920s, and that colonial farmers also regarded the species and an indicator of suitable land for raising wheat and sheep. Poole remarks on resemblance of the decorative grain to its sister species, Acacia melanoxylon (blackwood).[10] The number of posts produced in the period 1954–1968 was 2.7 million. Timber cutters were required to pay a royalty and obtain a license. The colonial diarist, George Fletcher Moore, noted the fine qualities of the timber and thought it suitable for cabinetry. The uses of the wood came to include pipes and walking sticks, and the construction of staircases and furniture. The tree is regarded as a good source of firewood, the value as charcoal was recorded by Ferdinand von Mueller in 1877. The charcoal was used for powering gas producing mechanisms attached to motor vehicles during petrol rationing in the mid-twentieth century.[1]

The seeds are consumed by regent parrots (Polytelis anthopeplus).[1]

Ecology

The species is a host to mistletoe species of genus Amyema, the host-parasite relationship having been researched near Geraldton with Amyema fitzgeraldii and elsewhere with Amyema preissii.[12][13]

Alkaloids

DMT in bark (up to 1.6%) and in leaves (0.6–1.0%) with some ß-carbolines, young leaves mainly containing tryptamine;[14] 0.72% alkaloids from leaves and stems, mostly tryptamine.[15]

Broad-leafed form gave 0.72% total alkaloid and narrow-leafed form gave 1.5% total alkaloid. Both collected Oct. White 1957[16] Broad-leaf A.acuminata phyllodes resulted in 51% MTHBC, 32% DMT, 16% tryptamine, 0.5% Harman, 0.4% 3-methyl-Quinoline (not verified), 0.3% N-Methyl-PEA, and 0.1% PEA.[17]

See also

References

Notes

- Cunningham, Irene (1998). The trees that were nature's gift. WA: I. Cunningham. pp. 18–23. ISBN 978-0958556200.

- Catalog of Life

- "Acacia acuminata". FloraBase. Western Australian Government Department of Parks and Wildlife.

- Maslin et all. (1999). Genetic diversity within and divergence between rare and geographically widespread taxa of the Acacia acuminata Benth. (Mimosaceae) complex. Heredity, 88, 250-257.DOI: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800036

- "Noongar names for plants". kippleonline.net. Archived from the original on 2016-11-20. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Dryland Area Species

- Florabank. (2008). Acacia acuminata fact sheet. Retrieved from: http://www.florabank.org.au/lucid/key/species%20navigator/media/html/Acacia_acuminata.htm

- Qualities Required of Species for Agroforestry and Fuelwood Archived May 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Aussie Fantom Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Lane-Poole, C. E. (1922). A primer of forestry, with illustrations of the principal forest trees of Western Australia. Perth: F.W. Simpson, government printer. p. 90. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.61019. hdl:2027/umn.31951p011067200.

- Sandalwood Guide for Farmers - Forest Products Commission - April 2007

- Davidson, Neil J.; Pate, John S. (1992). "Water Relations of the Mistletoe Amyema fitzgeraldii and its Host Acacia acuminata". Journal of Experimental Botany. 43 (12): 1549–1555. doi:10.1093/jxb/43.12.1549.

- Lamont, B. B.; Southall, K. J. (May 1982). "Distribution of Mineral Nutrients Between the Mistletoe, Amyema preissii, and its Host, Acacia acuminata". Annals of Botany. 49 (5): 721–725. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086300.

- recent Net reports, Australian underground info

- White, E.P. 1957. "Evaluation of further legumes, mainly Lupinus and Acacia species for alkaloids." New Zealand J. Sci. & Tech. 38B:718-725.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-15. Retrieved 2015-01-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Analysis conducted online

General references

- "Acacia acuminata Benth". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- "Acacia acuminata". Flora of Australia Online. Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government.

- "Acacia acuminata". FloraBase. Western Australian Government Department of Parks and Wildlife.

- D. J. Boland; et al. (1984). Forest Trees of Australia (Fourth Edition Revised and Enlarged). CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria. ISBN 978-0-643-05423-3.

- A. A. Mitchell and D. G. Wilcox (1994). Arid Shrubland Plants of Western Australia (Second and Enlarged ed.). Department of Agriculture, Western Australia. ISBN 978-1-875560-22-6.

- "Acacia acuminata". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

External links

Data related to Acacia acuminata at Wikispecies

Data related to Acacia acuminata at Wikispecies