Ecocrop

Ecocrop was a database used to determine the suitability of a crop for a specified environment.[1] Developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) it provided information predicting crop viability in different locations and climatic conditions.[2] It also served as a catalog of plants and plant growth characteristics.[3]

| Producer | Food and Agriculture Organization (Italy) |

|---|---|

| Languages | English |

| Access | |

| Cost | Open access |

| Coverage | |

| Disciplines | Plant taxonomy |

| Geospatial coverage | all regions |

| No. of records | 2,300 |

| Links | |

| Website | http://ecocrop.fao.org/ecocrop/srv/en/home |

History

Ecocrop first emerged in 1991 after planning and initial expert consultancies were completed concerning the development of a database.[4] This system was developed by the Land and Water Development Division of FAO (AGLL) and was launched in 1992.[4] The goal was to create a tool that can identify plant species for given environments and uses, and as an information system contributing to a Land Use Planning concept.[4] In 1994, the Ecocrop database already permitted the identification of more than 1,700 crops and 12-20 environment requirements covering all of the agro-ecological settings of the world.[4] Succeeding iterations of the database from 1998 to 1999 mainly involved improvements to the user interface. By the year 2000, the database included 2,000 species and 10 additional descriptors.[4] This number was later expanded with the addition of 300 crop species.[4]

As of February 2020 the Ecocrop database hosted at fao.org is not accessible.

The Ecocrop model

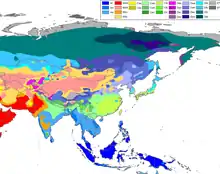

The Ecocrop model determines a crop's suitability to a location by evaluating different variables.[5] Specifically, the plant descriptors include category, life form, growth habit, and life span while environmental descriptors include temperature, precipitation, light intensity, Köppen climate classification, photoperiodism, latitude, altitude, and other soil characteristics.[6] The crop database is particularly useful if there is no alternative but to use environmental ranges.[7] Once these inputs are determined, the system produces a suitability index as a percentage.[8] The suitability index score is generated from 0 to 1 with the former indicating totally unsuitable while the latter indicates optimal or excellent suitability.[5] The output also include separated suitability values for temperature and precipitation.[8]

As a prediction model, the Ecocrop algorithm yields data that are more generic than those produced by other models such as DOMAIN and BIOCLIM.[7] The information is generic with respect to the nature of the requirements and is attributed to the lack of information concerning specific crops.[9] Another limitation is that the results depend solely on bioclimatic factors and discounts other variables such as soil requirements, pests, and diseases.[2]

Ecocrop evaluates whether climatic conditions are adequate within a growing season for temperature and precipitation every month.[10] It involves the calculation of climatic suitability based on rainfall and temperature marginal and optimal ranges.[10]

Other uses

Aside from serving as a plant identifier, Ecocrop is also used for other purposes. For instance, it can assess the influence of future climate change on crop suitability.[5] It can also be used to project crop yields using the database's information on optimal and absolute crop growing conditions (minimum temperature, maximum temperature, precipitation values, values that define temperature and precipitation extremes).[11]

References

- "FAO Ecocrop". ECHOcommunity.org. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- Robyn, Johnston; Hoanh, Chu Tai; Lacombe, Guillaume; Lefroy, Rod; Pavelic, Paul; Fry, Carolyn (2012). Improving water use in rainfed agriculture in the Greater Mekong Subregion.: Summary report. [Summary report of the Project report prepared by IWMI for Swedish International Development Agency (Sida)]. Stockholm: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). p. 14. ISBN 9789290907480.

- Organization, World Meteorological (2005). Monitoring and Predicting Agricultural Drought: A Global Study. New York: Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 287. ISBN 9780195162349.

- "Credits". ecocrop.fao.org. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- Rosenstock, Todd S.; Nowak, Andreea; Girvetz, Evan (2018). The Climate-Smart Agriculture Papers: Investigating the Business of a Productive, Resilient and Low Emission Future. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Open. p. 41. ISBN 9783319927978.

- "Crop Ecological Requirements Database (ECOCROP) | Land & Water | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations | Land & Water | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2019-07-02.

- Filho, Walter Leal (2011). The Economic, Social and Political Elements of Climate Change. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 708. ISBN 9783642147753.

- Hope, Elizabeth Thomas (2017). Climate Change and Food Security: Africa and the Caribbean. Oxon: Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 9781138204270.

- Ponce-Hernandez, Raul; Koohafkan, Parviz; Antoine, Jacques (2004). Assessing Carbon Stocks and Modelling Win-win Scenarios of Carbon Sequestration Through Land-use Changes. Rome: FAO. p. 61. ISBN 9789251051580.

- Yadav, Shyam Singh; Redden, Robert J.; Hatfield, Jerry L.; Lotze-Campen, Hermann; Hall, Anthony J. W. (2011). Crop Adaptation to Climate Change. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 358. ISBN 9780813820163.

- Millington, James D. A.; Wainwright, John (2018-09-27). Agent-Based Modelling and Landscape Change. Basel: MDPI. p. 69. ISBN 9783038422808.