Actors of the Comédie-Française

Actors of the Comédie-Française[note 1] is an oil on panel painting in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, by the French Rococo artist Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721). Completed in the 1710s, it forms a half-length five-figure composition, one of the rarest cases in Watteau's body of work, and has been given different interpretations by scholars, who believed it to be either a theatrical scene featuring commedia dell'arte masks or group portrait of Watteau's acquaintances. Because of that, the painting has been known under a number of various titles; its traditional naming in Western scholarship, Coquettes qui pour voir, is derived from anonymous verses which the painting was reproduced with in Jean de Jullienne's four-volume edition of prints after Watteau's works.

| Coquettes qui pour voir | |

|---|---|

| Actors of the Comédie-Française | |

| |

| Artist | Antoine Watteau |

| Year | Between 1711 and 1718 See § Dating |

| Catalogue | H 30; G 78; DV 36; R 107; HA 154; EC 162; F B32; RM 118; RT 77 |

| Medium | oil on panel |

| Dimensions | 20 cm × 25 cm (7.9 in × 9.8 in) |

| Location | The Hermitage, Saint Petersburg |

| Accession | ГЭ-1131 |

By the middle of the 18th century, Coquettes belonged to Louis Antoine Crozat, Baron de Thiers, a nephew of the Parisian merchant and art collector Pierre Crozat; shortly after his death in 1770, the painting, along with a most part of the collection he owned, was acquired for Catherine II of Russia in 1772. Since then the painting was held among the Russian imperial collections in the Hermitage and, after the 1850s, in the Gatchina Palace; in the 1920s, it was transferred to the Winter Palace, where it currently remains as part of the Hermitage Museum permanent exhibition.

Description

Composition

Actors of the Comédie-Française is an oil painting on a pearwood panel that measures approximately 20 by 25 cm,[13][14] showing five half-length figures in dark background standing around a stone balustrade; most of the five characters can be related to extant drawings, either directly or through comparable studies in Watteau's body of work. The painting is generally in good condition, despite losses and restorations underwent in the past.[15] Damages include a restored crack to the right of the old man's cape; gaps in shadows, more importantly at the bottom edge and around the girl's head; chippings painted over the girl's left shoulder.[16] X-ray analysis of the painting, performed by Soviet scholars in the 1970s, revealed alterations made to the female figure on the left of the composition during its production.[1]

The rightmost figure is an outwardly old man dressed in a skullcap; he stands upon a cane in the left hand, while holding a mushroom hat in the right hand. Also present in Marriage Contract and Country Dancing (now in the Prado, Madrid),[17] L'Accordee du Village (now in Sir John Soane's Museum, London), and possibly in The Shepherds (now in the Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin),[18] he is generally associated with an early full-length sanguine study (PM 64; RP 75), engraved[note 2] by Jean Audran.[19] It has been noted, however, that the study is probably a reduced version of a larger, more vibrant study drawn from life, similar to other studies such as the ones located in the British Museum, London (PM 84; RP 130), and in the Teylers Museum, Harlem (PM 53; RP 135), respectively. Given the rendering of the hand holding the cane and especially the quality of the man's face, it has been suggested that Watteau relied on additional drawings for his painting.[20] Some authors, most notably the Hermitage staff curator Inna Nemilova, related the painting to a sheet in the Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin (PM 914; RP 653), showing two studies of the similarly dressed man holding a cane, engraved by François Boucher as two separate etchings[note 3] published in the Recueil Jullienne; one of Boucher's etchings was reproduced by Claude Du Bosc.[21]

.jpg.webp) Watteau, detail from Actors of the Comédie-Française, showing the old man

Watteau, detail from Actors of the Comédie-Française, showing the old man_(detail%252C_the_old_man_holding_the_hat).jpg.webp) Watteau, detail from Marriage Contract and Country Dancing showing the similar character. Prado, Madrid

Watteau, detail from Marriage Contract and Country Dancing showing the similar character. Prado, Madrid Watteau, detail from The Shepherds showing the musette player, believed to be the same sitter as in Actors of the Comédie-Française. Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin

Watteau, detail from The Shepherds showing the musette player, believed to be the same sitter as in Actors of the Comédie-Française. Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin Watteau, Two Studies of an Actor, ca. 1715–1721, believed to depict the same sitter as Actors of the Comédie-Française. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin

Watteau, Two Studies of an Actor, ca. 1715–1721, believed to depict the same sitter as Actors of the Comédie-Française. Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin

By the balustrade's other side, a young girl is shown in a lightly colored, striped dress with ruff, standing behind a black boy servant in green-striped clothes; over the girl's shoulder, a head of a young man, dressed as Mezzetino, appears in a large motley beret. The girl and the boy's figures are usually related to a Louvre drawing of eight head studies, with the boy's head directly adopted into the Hermitage painting; the girl's figure is also thought to be related to the Louvre drawing, notably used in a version of The Embarkation for Cythera located in the Charlottenburg Palace.[22] Young people of color were a recurrent theme in Watteau's paintings and drawings, possibly influenced by works of Paolo Veronese; these are also present in Les Charmes de la vie (Wallace Collection, London), La Conversation (Toledo Museum of Art), and Les Plaisirs du Bal (Dulwich Gallery, London). The head of the young man has no directly related drawings, but is notably present in The Italian Comedians now in the Getty Museum, Los Angeles; the figure has also been associated by Nemilova with a head on a sheet of studies located in a private collection in New York City (PM 746; RP 456) and, to a lesser success, with a figure from a sheet now in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (PM 665; RP 475),[23] while Yuri Zolotov thought the head to be related with Il Capitano's figure present in the Louvre-owned Pierrot.[24]

Opposite to the old man is a young woman turned to the right in profile, wearing Polish-styled red dress and white chipper, leaning on the balustrade and holding a black mask in the right hand; from the X-ray analysis, it has been found that she was to be bareheaded, wearing a different attire, and had to have her mask placed on the balustrade rather than holding it.[25] Similarly to the old man's figure, the woman's figure has been related to an early, small, full-length study (RP 44) of a similarly dressed yet differently posed woman, that has been adopted into a more detailed drawing, later used in The Polish Woman (now in the National Museum, Warsaw). Various studies of women’s hands holding masks have been related to the painting, with a study in the Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin (PM 828; RP 417), regarded as the closest. There is also a now untraced sanguine and black chalk study of the woman and the boy (PM 541) that closely corresponds, albeit in reverse, with the painting; coming from these grounds, some authors considered the drawing to be a preliminary study,[26] but Eidelberg questions that relation, as well as the sheet's authenticity.[27]

Identity of subjects

Until the middle of the 20th century, sources and studies on Watteau variously defined the work's subject. In notes to Pellegrino Antonio Orlandi's Abecedario pittorico, Pierre-Jean Mariette referred to the work as Coquettes qui pour voir galans au rendez vous (transl. "Coquettish women, who to meet gallant men go around..."), after the first verses of quatrains accompanying Thomassin's engraving for the Recueil Jullienne; Mariette thought the panel depicts "people in disguise for a ball, among whom is one dressed as an old man."[28] François-Bernard Lépicié refers to the composition as Retour de Bal in a 1741 obituary of Henri Simon Thomassin, believing the figures to be returning from a ball;[29]:569[30] in contrary, Catalogue Crozat of 1755 and Dezallier d'Argenville fils described it as a depiction of masked figures preparing for a ball.[31][32]

Later sources, more prominently in France and Russia, similarly had various definitions on the subject: Johann Ernst von Munnich refers to the work as Personnages en masques (transl. "Characters in Masks") in the manuscript catalogue of the Hermitage collection;[33] the Hermitage's 1797 catalogue features the title The Mascarade,[34] whereas the 1859 inventory registry features only the work's description—"two women, talking with two men, and a negro beside them".[35][36] In his writings, Pierre Hédouin referred to the work as Le Rendez-vous du bal masqué,[37] before Edmond de Goncourt's Catalogue raisonné... introduced the Mariette-mentioned title into common use.[38]

In an 1896 article published in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, the French author Gaston Schéfer was the first to consider The Coquettes to be based on portrait drawings rather than being a theatrical scene. Schéfer suggested from an inscription under Boucher's etching after the Berlin drawing, found in a copy of Figures des differents caracteres held by the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, that the old man on the right of the painting was modelled after Pierre-Maurice Haranger, a canon of the Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois who was a close friend of Watteau; the lady in red was thought by Schéfer to be the Comédie-Française actress Charlotte Desmares,[note 4] based on comparison of the composition with Lepicié's etching of her portrait by Charles-Antoine Coypel.[lower-alpha 1] Later in the early 1900s, playwright Virgile Josz presumed the painting to be a depiction of commedia dell'arte masks, with the old man as Pantalone, the women as Rosaura and Isabella, and the young man as Scapino;[42] in later years, these points were adopted by a number of scholars[note 5] Josz's contemporary Louis de Fourcaud considered figures to be a family group dressed for an elegant masquerade."[48][49]

In a 1950 monograph on Watteau, Hélène Adhémar identified the lady in red as Charlotte Desmares, similarly to Schéfer;[50] Adhémar's point was furthered in Karl Parker and Jacques Mathey's 1957–1958 catalogue of Watteau drawings; they concluded that the old man could be another Comédie-Française player, Pierre Le Noir.[note 6] In the Soviet Union, the Hermitage staff member Inna Nemilova supported these points, and also concluded the young man to be Philippe Poisson.[52][53] In addition, Nemilova pointed out Desmares could be possibly depicted by Watteau in both versions of The Embarkation for Cythera, and also other canvas[note 7] and various drawings.[54]

Provenance

In an article published in the March 1928 issue of Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Russian scholar Sergei Ersnt reported that the panel has a label on the verso stating that it was owned by the painter Nicolas Bailly[note 8] (1659–1736), a curator of the royal collections who authored a 1709–1710 inventory of the paintings of King Louis XIV;[56] in 1984, Rosenberg said that he wasn't surprised about Ernst's report, given Bailly's relations within artistic circles.[note 9] The label has been deciphered as "N Bailly [prove]nant <…> de lonay aux gallery;" Nemilova noted that de Lonay was an expert mentioned by the Parisian merchant and art collector Pierre Crozat — once a patron of Watteau — in his last will and testament.[58][3]

Shortly after Bailly's death, Coquettes... came into possession of Louis Antoine Crozat, Baron de Thiers, Pierre Crozat's nephew; it was present in the 1755 catalogue of Crozat de Thiers' collection,[31] and later in the 1771 inventory compiled by François Tronchin upon the collector's death.[59] In 1772, the Crozat collection, with Coquettes being its part, was acquired by Catherine the Great, and was mostly transitioned into the Russian empress and her successors' collection in Saint Petersburg, now known as the Hermitage Museum.[60] At some point in the mid-19th century, the panel was taken to the Gatchina Palace; it was present in the Oval Chamber, a personal room of Tsar Paul I in the palace's ground floor, where it was photographed in the early 1910's.[61] In 1920, Coquettes qui pour voir was restored to the Hermitage; currently it's on display in room 284, formerly the second room of military pictures in the Winter Palace.[62]

Authorship

Authenticity of the panel has never been seriously questioned until the early 20th century, when Russian scholar Nicolas Wrangel considered it a copy by Philippe Mercier, a prominent English follower of Watteau; in a letter to Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann, a German scholar who compiled an album and catalogue of Watteau's work, Wrangel pointed out that the blond actress lacks the coiffure seen in Thomassin's print, and there are also differences in the actor at the right.[55] On the Russian fellow's advice, Zimmermann chose to classify it among the "doubtful pictures".[63][64] In the early 1970s, the panel's authenticity was questioned in the four-volume survey edited by Jean Ferré that, based on Wrangel's doubts and inconsistency found in contemporary sources, included the work among "attributed to Watteau."[65] Later studies have ruled possible doubts out, given the work's condition as well as preparatory drawings and Thomassin's print; in the 1960s, Nemilova presumed Wrangel have been led to his conclusion because of the work's presence in the Gatchina Palace;[66] much later, Martin Eidelberg adds that Mercier could not paint with the same characteristics and artistic level Watteau had.[55]

Dating

Dating of the painting remains somewhat imprecise.[12] In 1950, Adhémar attributed the work to the period from Spring to Autumn of 1716.[67] In a 1957 book Great French Painting in the Hermitage, Charles Sterling[note 10] suggested a 1716–1717 dating, while in 1959, Jacques Mathey proposed a relatively early date of 1714.[69] Regarding aforementioned datings as too late, Nemilova dated Actors ... within a period of 1711–1712;[note 11] the Soviet scholar argued that the picture has similarities with another Watteau composition, Du bel âge...,[note 12] as it has characters depicted in half-length with compositional rhythm and visual features similar to these found on the Hermitage painting. In her dating, Nemilova also relied upon several other works attributed to the early 1710s by Adhémar and Mathey: La Conversation, The Dreamer, La Polonnoise, and Polish Woman; to Nemilova, the "Polish" dress of the model was the most important point for her dating, as Polish-styled costumes were fashionable in France during the early 1710s, in light of the then recent Battle of Poltava.[78]

In later publications, a variety of dating is also given. In a 1968 catalogue raisonné, Ettore Camesasca preferred 1717,[30] a dating also used by Donald Posner in 1984.[75] Others authors, such as Pierre Rosenberg,[79] Marianne Roland Michel,[lower-alpha 2] and Mary Vidal,[81] proposed a 1714-1715 dating; Roland Michel objected Nemilova's dating as too early and not taking into account the psychological study of subjects.[lower-alpha 2] In 2000, Helmut Börsch-Supan chose an even later dating to 1718,[82] and in 2002, Renaud Temperini proposed 1716–1717.[83]

Related works

Prints

Actors of the Comédie-Française was engraved in reverse for the Recueil Jullienne, a compilation of prints after Watteau's work published by his friend Jean de Jullienne in 1735, by Henri Simon Thomassin's. The print was cited in François-Bernard Lépicié's obituary notice for Thomassin that appeared in the March 1741 issue of the Mercure de France magazine.[29] Thomassin's print was mentioned by Pierre-Jean Mariette in Notes manuscrites, and served as a source to a number of pastiches.

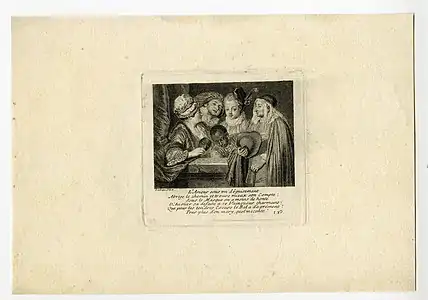

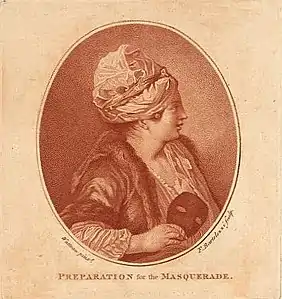

Thomassin's etching was anonymously reproduced as a miniature print, captioned L'Amour, sous un déguisment…. A Favourite Sultana (also called Preparation for the Masquerade), an oval stipple print depicting the turbaned woman at the right of Thomassin‘s engraving, was produced in London in 1785 by Italian-born artist Francesco Bartolozzi, and has the misleading declaration “Watteau pinxt."[84] Another engraving of the composition, called La Comédie italienne, was produced by Félix-Jean Gauchard after Thomassin’s print, to accompany the entry on Watteau published in Charles Blanc’s series Histoire des peintres des toutes les écoles. École français in 1862-63.[85][86]

Mascarade (also spelled Masquerade), a mezzotint by French-born English printmaker John Simon, was mentioned by Charles Le Blanc[87] and John Chaloner Smith[88][89] in their respective studies, and was presumed to be a repetition of Thomassin's print by some authors (notably including Dacier and Vuaflart[28]), given similarity in the number of characters.

Henri Simon Thomassin after Watteau, Coquettes qui pour voir, before 1731, etching. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid

Henri Simon Thomassin after Watteau, Coquettes qui pour voir, before 1731, etching. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid Anonymous artist after Watteau, L'Amour, sous un déguisment…, 1730s, etching

Anonymous artist after Watteau, L'Amour, sous un déguisment…, 1730s, etching Francesco Bartolozzi after Watteau, Preparation for the Masquerade, 1785, stipple engraving. Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Francesco Bartolozzi after Watteau, Preparation for the Masquerade, 1785, stipple engraving. Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg Félix Jean Gauchard after Watteau, La Comédie Italienne, ca. 1862–1863, woodcut. British Museum, London

Félix Jean Gauchard after Watteau, La Comédie Italienne, ca. 1862–1863, woodcut. British Museum, London

Exhibition history

| Year | Title | Location | Cat. no. | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1908 | Les anciennes écoles de peinture dans les palais et collections privées russes, by the Starye gody magazine | Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Saint Petersburg | 286 | [43]:729[90]:250[91] | |||||

| 1922–1925 | Temporary exhibition of new acquisition from French painting of the 17th and 18th centuries | Hermitage Museum, Petrograd (later Leningrad) | * | [46][45] | |||||

| 1955 | An Exhibition of French Art of the 15th-20th Centuries | Pushkin Museum, Moscow | * | [92] | |||||

| 1956 | An Exhibition of French Art of the 12th-20th Centuries | Hermitage Museum, Leningrad | * | [93] | |||||

| 1965 | Chefs-d'oeuvre de la peinture française dans les musees de l'Ermitage et de Moscou | Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, Bordeaux | 43 | [94]:611[95] | |||||

| 1965–1966 | Chefs-d'oeuvre de la peinture française dans les musees de l'Ermitage et de Moscou | Louvre, Paris | 41 | [96][97]:614[95] | |||||

| 1972 | Watteau and His Time | Hermitage Museum, Leningrad | 5 | [98][10] | |||||

| 1980 | Les arts du théâtre de Watteau à Fragonard | Galerie des Beaux-Arts, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, Bordeaux | 67 | [12] | |||||

| 1984 | Антуан Ватто. 300 лет со дня рождения | Hermitage Museum, Leningrad | * | [99][100]:78 | |||||

| 1984–1985 | Watteau 1684–1721 | National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris; Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin | P. 29 | [101]:359 | |||||

| General references: Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, p. 313, Nemilova 1985, p. 445, Eidelberg 2019. "*" denotes an unnumbered entry. | |||||||||

Quotes

- "L'étude n" 198, gravée par Boucher, nous représente le barbon de la Comédie italienne, posé de trois quarts, assis sur une chaise. Il est coiffé d'une perruque à cheveux longs. Une autre étude (n° 69), également gravée par Boucher, le figure de face, un large chapeau sur la tète. Sous l'étude n" 198, Mariette a écrit : « Portrait de l'abbé Larancher. » C'est ainsi qu'il est nommé également dans le Mercure. Mais il a effacé le nom et l'a corrigé par « Aranger », selon l'orthographe de l'Abecedario. Un prêtre sous un tel habit, voilà qui paraît surprenant; mais au XVIIIe siècle l'Eglise avait sa bonhomie. Watteau ne croyait pas plus faire œuvre de scandale en déguisant l'abbé Haranger sous la perruque de Géronte que Cochin en dessinant l'abbé Pommyer sous l'habit du Paysan de Gandelu. D'ailleurs, l'abbé Haranger avait une si bonne physionomie de théâtre que l'on rencontre son portrait sous un autre nom : « La Thourilère, La Thorillière. » Peut-être même une autre étude de l'abbé Haranger a-t-elle servi au vieillard du tableau des Coquettes. Mais ici la ressemblance n'est pas assez directe pour qu'on puisse rien affirmer.

Ce tableau des Coquettes n'est probablement fait que de portraits, de ces têtes d'etudes que Watteau crayonnait sur ses cahiers. Quels portraits? nous l'ignorons. Tout au plus hasarderons-nous quelque supposition vraisemblable sur cette jeune femme au nez retroussé, aux joues rebondies, que l'on voit à droit, coiffée d'un grand bonnet oriental et qui rappelle Mlle Desmares, de la Comédie Française. Assurément, ce n'est pas la Pèlerine dont Watteau a tracé la frête silhouette dans les "Figures de Mode"; cette figurine est si menue que l'on a peine à distinguer sa physionomie. Mais le grande portrait de Lepicié nous donne assez exactement le visage et les formes abondantes de la comédienne pour que notre hypothèse soit autorisée."[41] - "Inna Nemilova dated this work 1710–1712, which seems very early in view of the treatment of the figures and especially of the psychological perception evident in the faces, in which portraits of Mlle Desmares, of La Thorilliere and of other actresses have been seen; we are inclined to date it not earlier than 1714–1715. It is tempting to suggest that this might be a pendant to Du Bel âge où les jeux (Of the good age when games…, DV 94), which Camesasca takes to be a pendant to Entretiens badins (Playful Conversation, a lost work, D.-V. 95). The latter two works were printed on the same plate of the Recueil Jullienne, though this is not, as we shall see, sufficient proof itself. If a reason is needed for suggesting that Les Coquettes and Du Bel âge could be pendants we need only look at the compositions. Both show four half-length figures, three around a table, one standing; the mask held by the actress in the Hermitage painting is replaced in Du Bel âge by a score. However, we do not know the dimensions of the latter painting, though logic suggests they match those of Les Coquettes. And above all we do not know how the picture was painted. Were this hypothesis correct, it would imply a similar date, that is, around 1714–1715. But the absurdity of dating a print and of coupling two works as pendants when the dimensions of one of them are not known is immediately obvious."[80]

Notes

- Russian: «Актёры Французского театра»,[1] usually translated into English as Actors of the Comédie-Française;[2][3][4]:431 a variant title with the hyphen omitted, Actors of the Comédie Française, is known as well.[5][6]

Other Russian titles, based on the painting's interpretation as portrait of the Comédie-Française players, are «Актёры Французской комедии»[7] and «Портрет французских актёров».[8]:187 Related titles in English and French include Actors of the Théâtre Français,[9] The French Comedians,[10]:734 The Comedians,[11] Acteurs de la Comédie-Française,[12] and Les comediens français.[2] - Folio 157 in Figures de differents caracteres

- Folios 69 and 198 in Figures de differents caracteres.

- Christine Antoinette Charlotte Desmares (1682–1753) performed in the Comédie-Française from 1690 to 1721; at some point, she was a mistress of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans. According to François Moureau's article "Watteau in His Time" published in the Watteau, 1684–1721 exhibition catalogue, Desmares "had numerous reasons for meeting Watteau."[39] Nemilova presumed that Watteau was introduced to Desmares by his friend, Mercure de France editor Antoine de Laroque.[40]

- Virgile Josz’s description of Coquettes... had been adopted by a number of scholars, including the Russians Alexandre Benois,[43]:729[44] Valentin Miller,[45] and Sergei Ersnt,[46]:172–173 as well as the Hermitage Museum's 1958 catalogue of the painting collection.[47]

- Pierre Le Noir (1659–1731) was a son of François Le Noir dit La Thorillière, a prominent actor associated with Molière’s company. He joined the royal troupe in 1671, first as a touring artist; in 1684, Le Noir became a sociétaire of the Comédie-Française. Le Noir, also known as La Thorillière like his father was, mostly performed a manteau roles.[51]

- These include The Island of Cythera (The Embarkation’s preceding work, now in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt), The Dreamer (now in the Art Institute of Chicago), The Polish Woman (copy in the National Museum, Warsaw), and the lost La Polonnoise engraved by Michel Aubert.

- Zolotov 1973, p. 138, translated as Zolotov 1985, p. 98 and Zolotov 1996, p. 88, refers to the owner as N. Bolz which, according to Eidelberg, may be an error in transcription from French to Russian.[55]

- One of Bailly's sisters, Geneviève, had married the printmaker Simon Philippe Thomassin, whose son Henri Simon later engraved Actors of the Comédie-Française. Another sister, Jeanne, was married to the architect Jean Sylvain Cartaud, who designed Pierre Crozat's mansion in Paris on the Rue de Richelieu and owned a Watteau painting, The Enchanted Isle.[57]

- "The group of actors, sometimes called Return from the Ball, probably painted about 1716-17, brings together people of different ages, each described with the penetration and the tenderness of a portrait, each with his simplest expression, his most natural gesture, his pink, red, or black skin, his invariably sensitive but also invariably vigorous hands, their flesh solid and warm."[68]

- Claims of Nemilova's other or changed datings, notably claimed by Camesasca[30] and in the 1980 exhibition catalogue,[12] are considered erroneous.[70]

- Du bel âge…, also called Le Concert, is a presumably lost painting, believed to be a pendant to Les entretiens badins…, also presumed lost. These both were engraved separately by Jean Moyreau and Benoît Audran the Younger, respectively, and were published in the Recueil Jullienne, appearing on the same page. According to Goncourt, Du bel âge… was likely the painting formerly in Vivant Denon's collection, featured on the latter's sale in 1826.[71] According to Dacier and Vuaflart, Du bel âge… and Les entretiens badins… appeared on the market at the Caissotti sale in February 1850; however, it was stated by Eidelberg that the painting apppeared in the Caissotti sale featured six figures, whilst Du bel âge… has only four, therefore making the Caissotti painting a different composition.[72][73] Adhémar[74] and Posner[75] dated Du bel âge… ca. 1712, while Mathey[76] used a dating not earlier than 1704–1705; Camesasca used a 1710 dating.[77][73]

References

- Nemilova 1985, p. 444.

- Zolotov 1985, p. 98.

- Deryabina, Ekaterina (1989). "Antoine Watteau, 1684–1721, Actors of the Comédie-Française". In The Hermitage, Leningrad (ed.). Western European Painting of the 13th to the 18th Centuries. Introduction by Tatyana Kustodieva. Leningrad: Aurora Art Publishers. pp. 403–404. ISBN 5-7300-0066-9 – via the Internet Archive. Pl. 249–250

- Eidelberg, Martin (Winter 2006). "Philippe Mercier as a Draftsman". Master Drawings. 44 (4): 411–449. JSTOR 20444473.

- Jaques, Susan (2016). The Empress of Art: Catherine the Great and the Transformation of Russia. New York: Pegasus Books. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-60598-972-3. OCLC 945969675 – via the Internet Archive.

From France came works by Poussin, Antoine Watteau (Actors of the Comedie Francaise), and Jean-Siméon Chardin (The Laundress).

- Danielewicz, Iwona (2019). French Paintings from the 16th to 20th Century in the Collection of the National Museum in Warsaw. Complete Illustrated Catalogue Raisonné. Translated by Karolina Koriat, graphic design by Janusz Górski. Warsaw: The National Museum in Warsaw. pp. 346, 348. ISBN 978-83-7100-437-7. OCLC 1110653003. Catalogue note no. 279.

- German 2010, p. 105.

- Nemilova, I. S. (1971). "К вопросу о творческом процессе Антуана Ватто". In Libman, M. Y; et al. (eds.). Искусство Запада: Живопись. Скульптура. Архитектура. Театр. Музыка (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. pp. 181–195. OCLC 707104089.

- Grigorieva, M., ed. (1980). Hermitage, Leningrad. Great Museums of the World. Introduction by Vitaly Suslov; texts by T. Arapova and others; translated into English by Daryl Hyslop and Miriam Atlas. New York: Newsweek. pp. 11, 105–106. OCLC 1035610777 – via the Internet Archive.

- Cailleux 1972, p. 734: "[...] His theatre scenes, including the French Comedians (No. 5) are also the theatre of the Court."

- Baldini 1970, p. 109: "Antoine Watteau: The Comedians. Wood. 20 × 25 cm. This group of theatrical actors, a work that originates from the Crozat Collection, excels by reason pof the individuality of the portraits it contains. Here, in contrast to his imaginary theatre scenes, the artist's intention is to achieve true likenesses of these actors of the commedia dell’arte who are obviously still full of the roles they have played. The technical accomplishmment underlines the liveliness of the figures and has all the freshness of a sketch done from life."

- Les Arts du théâtre de Watteau à Fragonard (in French). Bordeaux: La Galerie. 1980. p. 110. OCLC 606308317.

- Nemilova 1964, p. 181; Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, p. 311.

- "Ватто, Антуан. 1684-1721 Актёры итальянской комедии 1711-1712 гг". Коллекции онлайн (in Russian). State Hermitage Museum. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- Montagni 1968, p. 113, translated as Camesasca 1971, p. 115; Zeri 2000, p. 26; Eidelberg 2019.

- Nemilova 1964, p. 181.

- Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, p. 312; Shvartsman 2013, p. 26.

- Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, p. 313.

- Parker & Mathey 1957–1958, p. 11, vol. 1, cat. no. 64; Rosenberg & Prat 1996, p. 120, vol. 1, cat. no. 75.

- Nemilova 1989, p. 146; Eidelberg 2019.

- Dacier & Vuaflart 1922, p. 141; Parker, pp. 21, 47, note no. 47.

- Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, pp. 89, 313.

- Nemilova 1989, pp. 142, 144; Shvartsman 2013, p. 46; Eidelberg 2019.

- Zolotov 1968, p. 30; Zolotov 1984, p. 65.

- Nemilova 1964, p. 181; Nemilova 1985, p. 444.

- Parker & Mathey 1957–1958, p. 309, cat. no. 541.

- Eidelberg 1985–1986, p. 104: "Likewise, I am surprised that Rosenberg (pp. 312-313) accepts a compositional drawing (PM 541) associated with the Hermitage's Retour du Bal. The drawing is weak, its direction corresponds not to the painting but to the engraving after the painting, and certain elements in the drawing such as the woman's bonnet and the placement of her mask correspond not to the initial stage of Watteau's painting (now known through x-rays) but, rather, to the final stage. All these problems lead me to conclude that this drawing, which has not been seen first-hand in many decades, should be considered a copy after the engraving."

- Dacier & Vuaflart 1922, p. 23.

- Lépicié, F. B. (March 1741). "Lettre sur la mort de M. Thomassin". Mercure de France (in French). pp. 568–570 – via Google Books.

- Montagni 1968, p. 113, translated as Camesasca 1971, p. 115.

- Crozat, Louis Antoine (1755). Catalogue des tableaux du cabinet de M. Crozat Baron de Thières á Paris (in French). Paris. p. 65 – via Google Books.

- Dezallier d'Argenville, Antoine-Nicolas (1757) [1749]. Voyage Pictoresque de Paris (in French). Paris. p. 140 – via Google Books.

Des personnages en masque se préparant pour le bal, par Watteau. Il y en a une estampe gravée par Thomassin.

- Munnich, Johann Ersnt von (1773–1783). Catalogue raisonné des tableaux qui trouvent dans les Galeries et Cabinets du Palais Impérial à Saint-Pétersbourg (in French). 1. p. 274. Cat. no. 873.

- Labensky, F. I., ed. (1797). Каталог картинам, хранящимся в Императорской Галерее Эрмитажа [Catalogue of Paintings housed in the Imperial Hermitage Gallery] (in Russian). 2. p. 55. Cat. no. 2545.

- Опись картинам и плафонам, состоящим в заведывании II отделения Императорского Эрмитажа [Inventory of paintings and plafonds in the office of the Second Department of the Imperial Hermitage Museum] (in Russian). 1859. Cat. no. 1699

- Nemilova 1964, pp. 81, 181; Nemilova 1970, pp. 145–146; Nemilova 1989, p. 133.

- Hédouin, P. (November 30, 1845). "Watteau: catalogue de son oeuvre". L'Artiste. pp. 78–80 – via Gallica. See also Hédouin 1856, p. 97, cat. no. 30

- Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, pp. 312–313; Eidelberg 2019: "Beginning with Edmond de Goncourt, it has become customary to assign the painting the awkward name of Coquettes qui pour voir, the opening words of the two quatrains that appears under the Thomassin engraving."

- Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, p. 477.

- Nemilova 1970, p. 156; Nemilova 1989, p. 152.

- Schéfer 1896, pp. 185–186.

- Josz 1903, pp. 329–330; Josz 1904, p. 146.

- Benois, Alexandre (November–December 1908). "Живопись эпохи барокко и рококо" [Painting of the Age of Baroque and Rococo]. 1908: Выставка картин. Старые годы (in Russian). pp. 720–734 – via the Internet Archive.

- Benois, Alexandre (1910). "La Peinture Française, Italienne et Anglaise aux xviie et xviiie siècles". In Weiner, P. P. (ed.). Les Anciennes écoles de peinture dans les palais et collections privées russes, représentées à l'exposition organisée à St.- Pétersbourg en 1909 par la revue d'art ancien "Staryé gody". Bruxelles: G. van Oest. pp. 105–119. OCLC 697960157 – via the Internet Archive.

D'un tout autre genre est un petit tableau de Watteau connu dans la gravure sous le nom «Les Coquettes». Le coloris n'en est pas recherché, mais les characters d'Isabelle la rusée, du stupide Pantalon, de la gaie Rosaure et du fourbe Scapin sont rendus avec amour et une grande finessee.

- Miller 1923, p. 59

- Ernst, Serge (March 1928). "L'exposition de peinture française des XVIIe et XVIIIe siecles au musée de l'Ermitage, a Petrograd (1922–1925)". Gazette des Beaux-Arts (in French). Vol. 17 no. 785. pp. 163–182. Retrieved March 29, 2019 – via Gallica.

- Hermitage Museum 1958, p. 270.

- Fourcaud 1904a, pp. 143–144.

- Nemilova 1964, pp. 81, 181; Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, p. 312; Nemilova 1989, p. 133.

- Adhémar 1950, p. 119: "[…] tandis que Mlle Desmares, coiffée d'un grand bonnet d'orientale, figure dans les Coquettes; elle aurait prête aussi ses traits à la figure centrale de L'Embarkment."

- Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, p. 478; Nemilova 1989, p. 140.

- Belova 2006, pp. 58–59.

- Zolotov 1973, p. 139; Nemilova 1982, pp. 131–133; Nemilova 1989, pp. 137–138, 140, 142, 144, 146.

- Nemilova 1964, pp. 86–87, 91.

- Eidelberg 2019.

- Ernst 1928, pp. 172–173.

- Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, pp. 311–312.

- Nemilova 1985, pp. 444–445.

- Stuffmann 1968, p. 135.

- Nemilova 1975, p. 436.

- Marishkina, V. F. Фотограф Императорского Эрмитажа [Photographer of the Imperial Hermitage] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: The State Hermitage Publishers. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-5-93572-732-1. OCLC 1022848562.

- Nemilova 1964, pp. 28-29, 182.

- Zimmermann, E. Heinrich (1912). Watteau: des Meisters Werke in 182 Abbildungen. Klassiker der Kunst (in German). 21. Stuttgart, Leipzig: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. pp. 122, 190–191. OCLC 561124140.

Grave par H. S. Thomassin fils (G. 78). Die Zeichnung des Bildes wirkt in der Reproduktion sehr flau. Baron Nikolaus Wrangel von der Ermitage in St. Petersburg war so liebenswürdig, mir mitzuteilen, daß er das Bild für eine Kopie von Mercier halte. Ich selbst konnte das Gemälde nicht untersuchen.

- Ettinger, P. D. (1912). "Rossica". Apollon (in Russian). No. 7. pp. 61–62.

- Ferré, Jean, ed. (1972). Watteau. 1. Madrid: Éditions Athena. vol. 1 pp. 151–152, vol. 3 p. 966. OCLC 906101135.

- Nemilova 1964, pp. 28–29, 181; Nemilova 1982, p. 133; Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, pp. 311–312.

- Adhémar 1950, pp. 119, 220, cat. no. 154, pl. 84.

- Sterling 1958, p. 41.

- Mathey 1959, p. 68.

- Nemilova 1985, p. 445; Zolotov 1985, p. 100.

- Goncourt 1875, pp. 161–162.

- Dacier & Vuaflart 1922, p. 45.

- Eidelberg, Martin (August 2020). "Du Bel âge". A Watteau Abecedario. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Adhémar 1950, p. 210, cat. no. 84, pl. 37.

- Posner 1984, p. 290.

- Mathey 1959, p. 66.

- Montagni 1968, p. 98, translated as Camesasca 1971, p. 100

- Nemilova 1964, p. 182; Nemilova 1970, p. 156; Nemilova 1985, p. 445.

- Grasselli, Rosenberg & Parmantier 1984, p. 312.

- Roland Michel 1984, p. 217.

- Vidal, Mary (1992). Watteau's Painted Conversations: Art, Literature, and Talk in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century France. New Haven, London: Yale University Press. p. 146. ISBN 0-300-05480-7. OCLC 260176725. Ill. 142

- Börsch-Supan 2000, pp. 46–47.

- Temperini 2002, p. 145, cat. no. 77.

- Roland Michel 1986, p. 55.

- Dacier & Vuaflart 1922, p. 23; Eidelberg 2019.

- Maurouard, Elvire Jean-Jacques (2005). Les beautés noires de Baudelaire. Paris: Karthala. p. 158. ISBN 2-84586-651-8. OCLC 1078667797 – via Google Books.

- Le Blanc, Charles (1854–1890). Manuel de l'amateur d'estampes (in French). 3. Paris: E. Bouillon. p. 521. OCLC 793563927 – via the Internet Archive.

190. Mascarade, cinq figures : Watteau. In-fol.

- Smith, John Chaloner (1884). British Mezzotinto Portraits. 3. London: H. Sotheran. p. 1129. OCLC 679810041 – via the Internet Archive.

175. Masquerade. Watteau. Group of five figures, T. Q. L., lady in centre, holding out her dress, bust in grove in background to left. Under, Watteau Pinx. I. Simon fecit., 8 verses. In this small ——— Vertue lost. H. 14 ; Sub. 12 ⅝ ; W. 9 ⅞.

- Smith, John Chaloner (1883). British Mezzotinto Portraits. 4.2. London: H. Sotheran. p. 1863. OCLC 1041620630 – via the Internet Archive.

175a. Companion. ID. Group of five figures, T. Q. L., black boy in centre, lady with mask to left. Under, Watteau pinxt. J. Simon fec et ex. (8 verses.) Past the delights —Spouse adorns. Same dimensions as 175.

- Weiner, P. P. de (October 1908 – March 1909). "Portraits anciens à Saint-Pétersbourg (Exposition de)". L'Art et les Artistes (in French). 8: 243–256 – via Gallica.

Une autre oeuvre de lui, qui est remarquable, mais qui n’a pas la portée de la Sainte Famille, les Coquettes, fut jadis gravée par Thomassin et appartient également au palais de Gatchina.

- Benois 2006, pp. 18, 21.

- Pushkin Museum, Moscow (1955). Выставка французского искусства XV-XX вв. Каталог (exhibition catalogue) (in Russian). Moscow: Iskusstvo. p. 24.

- Hermitage Museum, Leningrad (1956). Выставка французского искусства XII-XX вв. (1956; Ленинград). Каталог (in Russian). Moscow: Iskusstvo. p. 12.

- Charensol, Georges (June 15, 1965). "Les musées de Russie a Bordeaux". Revue des Deux Mondes (in French): 607–613. JSTOR 44590025.

De la maturité date Le Retour du Bal, où, pense-t-on, Watteau a groupé autour d'un négrillon, quatre acteurs du Théâtre Français.

- "French Paintings from the Hermitage and Pushkin Museum". French News: Theatre and Arts. No. 29. Autumn 1965. p. 25 – via Google Books.

- Lemoyne de Forges, Marie-Thérèse, ed. (1965). Chefs-d'oeuvre de la peinture française dans les musées de Léningrad et de Moscou (exhibition catalogue). Paris: Ministère d'État des affaires culturelles. pp. XV, 108–109; cat. no. 41. OCLC 1138863.

- Charensol, Georges (October 15, 1965). "L'Ermitage au Louvre". Revue des Deux Mondes (in French): 610–616. JSTOR 44591522.

Une œuvre aussi médiocre n'avait certainement pas sa place à côté du Retour du Bal qui fut reproduit en gravure sous le titre Coquettes qui pour voir galants au Rendez-Vous, ce qui correspond assez mal au sujet qui montre deux ravissantes filles à mi-corps avec un petit nègre, un personnage de comédie et un père noble son vaste chapeau à la main. Watteau a soit peint des acteurs du Théâtre Français, soit déguisé les membres de la famille Bailly à qui il destinait le tableau. Acquis en 1755 par Crozat il fut acheté à la vente de 1772 par la Grande Catherine.

- Hermitage Museum, Leningrad (1972). Ватто и его время. Leningrad: Avrora. pp. 12, 21. OCLC 990348938.

- Deryabina, E. V. (1987). "Антуан Ватто. 300 лет со дня рождения". Сообщения Государственного Эрмитажа (in Russian). 52: 75. ISSN 0132-1501.

- "Художественная жизнь Советского Союза: июнь, июль, август". Iskusstvo (in Russian). November 1984. pp. 76–79. ISSN 0130-2523.

- Opperman, Hal (June 1988). "Watteau 1684-1721 by Margaret Morgan Grasselli, Pierre Rosenberg and Nicole Parmentier". The Art Bulletin. 70 (2): 354–359. JSTOR 3051127.

Watteau's approach to the theater changed with such works as Coquettes qui pour voir galants (no. 29) and Les habits sont italiens (lost) that represent, according to the best available but still unsatisfactory interpretation, portraits of his friends dressed up in theatrical costume to no particular end.

Bibliography

- Adhémar, Hélène (1950). Watteau; sa vie, son oeuvre (in French). Includes "L’univers de Watteau", an introduction by René Huyghe. Paris: P. Tisné. pp. 119, 220, cat. no. 154, ill. 84. OCLC 853537.

- Baldini, Umberto (1970) [first published in Italian in 1966]. The Hermitage, Leningrad. Great Galleries of the World. Translated from the Italian by James Brockway. New York: Newsweek. p. 109. OCLC 92662 – via the Internet Archive.

- Barker, G. W. (1939). Antoine Watteau. London: Duckworth. pp. 133–34. OCLC 556817570.

- Belova, Y. N. (2006). "Аттрибуция изображенных лиц на картине Антуана Ватто "Актёры французского театра" ["Attribution of persons portrayed by Antoine Watteau in his "Actors of Theatre French"]". Экспертиза и атрибуция произведений изобразительного искусства: материалы X научной конференции [Expertise and Attribution of Works of Fine Arts: Materials from the 10th Academic Conference] (in Russian). Moscow: Magnum Ars. pp. 58–63.

- Benois, A. N. (2006). "Выставка «Старых годов» (14 (27) ноября 1908 г., № 277)". Художественные письма, 1908–1917, газета «Речь». Петербург. Т. 1: 1908–1910 (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Sad Iskusstv. pp. 16–21. ISBN 5-94921-018-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bindman, David; Boucher, Bruce; Weston, Helen (2011). "Between Court and City: Fantasies in Transition". In Bindman, David; Gates Jr., Henry Louis (eds.). The Image of the Black in Western Art. Volume III: From the "Age of Discovery" to the Age of Abolition. Part 3: The Eighteenth Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press. pp. 92, 94, 96. ISBN 978-0-674-05263-5. OCLC 1052808812 – via the Internet Archive.

- Boerlin-Brodbeck, Yvonne (1973). Antoine Watteau und das Theater (in German). Basel: Universität Basel. pp. 155–156. OCLC 1965328.

- Börsch-Supan, Helmut (2000). Antoine Watteau, 1684-1721. Meister der französischen Kunst (in German). Köln: Könemann. pp. 46–47, ill. 38. ISBN 3-8290-1630-1. OCLC 925262301.

- Cailleux, Jean (October 1972). "'Watteau and his times' at the Hermitage". The Burlington Magazine. 114 (835): 733–734. JSTOR 877114.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Camesasca, Ettore (1971). The Complete Paintings of Watteau. Classics of the World's Great Art. Introduction by John Sunderland. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 115, cat. no. 162. ISBN 0810955253. OCLC 143069 – via the Internet Archive.

- Chegodaev, A. D. (1963). Антуан Ватто [Antoine Watteau]. Moscow: Iskusstvo. p. 17, ill. 13. OCLC 40315312.

- Dacier, Émile; Vuaflart, Albert (1922). Jean de Julienne et les graveurs de Watteau au XVIII-e siècle. III. Catalogue (in French). Paris: M. Rousseau. p. 23, cat. no. 36. OCLC 1039156495.

- Dargenty, G. (1891). Antoine Watteau. Les Artistes Célèbres (in French). Paris: Librarie de l'Art. p. 89. OCLC 1039952242 – via the Internet Archive.

- Debrunner, Hans Werner (1979). Presence and Prestige, Africans in Europe: A History of Africans in Europe Before 1918. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien. p. 93. OCLC 827630594 – via Google Books.

- Descargues, Pierre (1961). The Hermitage Museum, Leningrad. New York: Harry N. Abrams. pp. 36, 166–167. OCLC 829900432.

- Eideiberg, Martin (1985–1986). "Review: Watteau, 1684–1721". Master Drawings. 23–24 (1): 102–106. JSTOR 1553790.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eidelberg, Martin (January 2019). "Coquettes qui pour voir". A Watteau Abecedario. Archived from the original on April 4, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Fourcaud, Louis de (November 1901). "Antoine Watteau. VI. — L'invention sentimentale, l'effort technique et les pratiques de composition et d'exécution de Watteau (Suite)". La Revue de l'art ancien et moderne. 10 (56): 337–349 – via the Internet Archive.

- Fourcaud, Louis de (February 1904a). "Antoine Watteau: scenes et figures théatrales (I)". La Revue de l'art ancien et moderne (in French). 15 (83): 135–150 – via the Internet Archive.

- Fourcaud, Louis de (November 1904b). "Antoine Watteau: scenes et figures galantes". La Revue de l'art ancien et moderne (in French). 16 (92): 341–356 – via the Internet Archive.

- Gauthier, Maximilien (1959). Watteau. Les Grands Peintres. Paris: Larousse. Pl. 29. OCLC 1151682363 – via the Internet Archive.

- Georgi, J. G. (1794). Описание российско-императорскаго столичнаго города Санктпетербурга и достопамятностей в окрестностях онаго [The Description of the Russian Empire Capital City of Saint Petersburg and sights of interest in its vicinity] (in Russian). 2. Saint Petersburg. p. 478 – via the Russian State Library archive.

- German, M. Y. (1980). Antoine Watteau. Masters of World Painting. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-2221-5. OCLC 6998113 – via the Internet Archive.

- German, M. Y. (2010) [first published in 1980]. Антуан Ватто [Antoine Watteau] (in Russian). Moscow: Iskusstvo—XXI vek. ISBN 978-5-98051-067-1. OCLC 641954308.

- Glorieux, Guillaume (2002). À l'enseigne de Gersaint: Edme-François Gersaint, marchand d'art sur le pont Notre-Dame (1694-1750). Seysell: Editions Champ Vallon. pp. 227–228. ISBN 2-87673-344-7. OCLC 401692541 – via Google Books.

- Glorieux, Guillaume (2011). Watteau. Collection Les Phares (in French). Paris: Citadelles & Mazenod. pp. 168, 170–171; ill. 117. ISBN 9782850883408. OCLC 711039378.

- Goncourt, Edmond de (1875). Catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre peint, dessiné et gravé d'Antoine Watteau. Paris: Rapilly. pp. 74–75, cat. no. 78. OCLC 1041772738 – via the Internet Archive.

- Goncourt, Edmond de; Goncourt, Jules de (1880) [1860]. L'art du dix-huitième siècle. 1er fasc.: Watteau (3rd ed.). Paris: A. Quantin. p. 56. OCLC 1157138267 – via the Internet Archive.

- Grasselli, Margaret Morgan; Rosenberg, Pierre; Parmantier, Nicole; et al. (1984). Watteau, 1684-1721 (PDF) (exhibition catalogue). Washington: National Gallery of Art. ISBN 0-89468-074-9. OCLC 557740787 – via the National Gallery of Art archive.

- M. Hébert (1766). Dictionnaire pittoresque et historique... (in French). 1. Paris: C. Hérissant. p. 103. OCLC 921720076 – via Gallica.

- Hédouin, Pierre (1856). Mosaïque. Peintres, musiciens, littérateurs, artistes dramatiques à partir du 15e siècle jusqu'à nos jours. Paris: Heugel. p. 97, cat. no. 30. OCLC 1157159285 – via the Internet Archive.

- Hermitage Museum, Leningrad (1958). Отдел западноевропейского искусства: Каталог живописи: в 2 т. 1. Leningrad, Moscow: Iskusstvo. p. 270. OCLC 50467017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hermitage Museum, Leningrad (1976). Западноевропейская живопись: в 2 т. 1. Leningrad: Aurora. p. 189. OCLC 995091183.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huys, Jean-Philippe (2011). "Princes en exil, organisateurs de spectacles: Sur le séjour en France des électeurs Maximilien II Emmanuel de Bavière et Joseph-Clément de Cologne". In Duforcet, Marie-Bernadette; Mazouer, Charles; Surgers, Anne (eds.). Spectacles et pouvoirs dans l'Europe de l'Ancien Régime, XVIe - XVIIIe siècle (conference papers) (in French). Tübingen: Narr. pp. 127–157. ISBN 978-3-8233-6645-4. OCLC 760246397.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Josz, Virgile (1903). Watteau. Moeurs du XVIIIe siècle (in French). Paris: Société du Mercure de France. OCLC 900757508 – via Google Books.

- Josz, Virgile (1904). Antoine Watteau (in French). Paris: H. Piazza et cie. pp. 117 (reproduction of Thomassin's print), 146. OCLC 963518006 – via the Internet Archive.

- Kajdańska, Alexandra (2019). "Eighteenth-century dance costume and etiquette in Gottfried Taubert's Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister". Tauberts „Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister“ (Leipzig 1717) : Kontexte – Lektüren – Praktiken. Berlin: Frank & Timme. pp. 101–126. ISBN 978-3-7329-0428-0 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mantz, Paul (1892). Antoine Watteau. Paris: Librairie illustrée. pp. 181–182. OCLC 742536514 – via the Internet Archive.

- Mathey, Jacques (1959). Antoine Watteau. Peintures réapparues inconnues ou négligées par les historiens (in French). Paris: F. de Nobele. p. 68. OCLC 954214682.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, V. F. (1923). "Французская живопись XVII-го и XVIII-го в.в. в новых залах Эрмитажа". Город (in Russian). No. 1. pp. 52–78. OCLC 32361994.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mirzoeff, Nicholas (Summer 1994). "'Seducing Our Eyes': Gender, Jurisprudence, and Visuality in Watteau". The Eighteenth Century. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. 35 (2): 135–154. JSTOR 41467582.

- Mollett, John William (1883). Watteau. Illustrated Biographies of the Great Artists. London: S. Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington. p. 63. OCLC 557720162 – via the Internet Archive.

- Montagni, E. C. (1968). L'opera completa di Watteau. Classici dell'arte (in Italian). 21. Introduction by Giovanni Macchia. Milano: Rizzoli. p. 113; cat. no. 162; colorpl. XXIV. OCLC 1006284992. For the English edition, see Camesasca 1971.

- Moureau, François (1992). De Gherardi à Watteau. Paris: Klincksieck. p. 124. ISBN 978-2-25202-822-3. OCLC 614813362.

- Moureau, François (2011). Le goût italien dans la France rocaille: théâtre, musique, peinture (v. 1680–1750). Paris: Presses de l'Université Paris-Sorbonne. p. 83. ISBN 978-2-84050-731-4. OCLC 1114979618.

- Nemilova, I. S. (1964). Ватто и его произведения в Эрмитаже (Watteau et son œuvre à l'Ermitage) [Watteau and His Works in the Hermitage] (in Russian). Leningrad: Sovetskiy hudozhnik. OCLC 67871342.

- Nemilova, I. S. (1970). "Картина Ватто «Актёры французской комедии» и проблема портрета в творчестве художника [Watteau's painting Actors of the Comédie-Française and the matter of portrait in the artist's work]". In Izergina, A. N.; Nikulin, N. N. (eds.). Западноевропейское искусство [Western European Art] (in Russian). Leningrad: Aurora. pp. 145–157. OCLC 837241769.

- Nemilova, Inna (June 1975). "Contemporary French Art in Eighteenth-Century Russia". Apollo. 101 (160): 428–442.

- Nemilova, I. S. (1982). Французская живопись XVIII века в Эрмитаже (La peinture française du XVIIIe siècle, Musée de L'Ermitage: catalogue raisonné) [French Painting of the 18th centrty in the Hermitage Museum: Scientific Catalogue]. Leningrad: Iskusstvo. pp. 130–134, cat. no. 45. OCLC 63466759.

- Nemilova, I. S. (1985). Французская живопись XVIII века [French Painting of the 18th Century]. Государственный Эрмитаж. Собрание живописи (in Russian). Moscow: Izobrazitel'noe iskusstvo. pp. 242–243, ill. 35. OCLC 878889718.

- Nemilova, I. S. (1985). Французская живопись. XVIII век [French Painting: the 18th Century]. Государственный Эрмитаж. Собрание западноевропейской живописи: научный каталог в 16 томах. 10. Edited by A. S. Kantor-Gukovskaya. Leningrad: Iskusstvo. pp. 444–445, cat. no. 348. OCLC 22896528.

- Nemilova, I. S. (1989) [first published in 1973]. Загадки старых картин [Enigmas of Old Masters] (in Russian) (3rd ed.). Moscow: Izobrazitel'noe iskusstvo. ISBN 5-85200-017-5. OCLC 909190011.

- Nemilova, Inna (2013). "How Antoine Watteau's Italian Actors Became French". Hermitage Magazine. No. 20. pp. 154–159. ISSN 2218-0338.

- Neverov, O. Y.; Alexinsky, D. P. (2010). The Hermitage. Vol. 1: The Treasures of World Art. New York, Milan, St. Petersburg: Rizzoli, ARCA Publishers. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-8478-3503-4. OCLC 1193944908 – via the Internet Archive.

- Parker, Karl T. & Mathey, Jacques (1957–1958). Antoine Watteau: catalogue complet de son oeuvre dessiné. Paris: F. de Nobèle. OCLC 2039948.

- Parker, Karl T. (1970) [1931]. The Drawings of Antoine Watteau. New York: Hacker Art Books. p. 48. ISBN 0-87817-050-2. OCLC 680613312 – via the Internet Archive.

- Phillips, Claude (1895). Antoine Watteau. London: Seeley and co. Limited. pp. 70, 72. OCLC 729123867 – via the Internet Archive.

- Pilon, Edmond (1924) [1912]. Watteau et son école. Paris, Bruxelles: Librarie Nationale D'art dt d'histoire, G. Van Oest & cie. p. 135. OCLC 744619923 – via Google Books.

- Piotrovsky, Mikhail (2013). "Watteau". Hermitage Magazine. No. 20. pp. 144–147. ISSN 2218-0338.

- Posner, Donald (1984). Antoine Watteau. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 290. ISBN 0-8014-1571-3. OCLC 10736607 – via the Internet Archive.

- Réau, Louis (1928). "Catalogue de l'art français dans les musées russes". Bulletin de la Société de l'histoire de l'art français: 167–314 – via Gallica. Cat. no. 417.

- Réau, Louis (1928–1930). "Watteau". In Dimier, Louis (ed.). Les peintres français du XVIII-e siècle: Histoire des vies et catalogue des œuvres (in French). 1. Paris: G. Van Oest. p. 34, cat. no. 57. OCLC 564527521.

- Roland Michel, Marianne (1980). Antoine Watteau: das Gesamtwerk (in German). Translated from the French by Rudolf Kimmig. Frankfurt: Ullstein. p. 42, cat. no. 118. ISBN 3-548-36019-X. OCLC 69202887.

- Roland Michel, Marianne (1984). Watteau: un artiste au XVIII-e siècle. Paris: Flammarion. pp. 216–217, 305; ill. 215. ISBN 0862940494. OCLC 417153549.

- Roland Michel, Marianne (1986). "Watteau and England". In Hind, Charles (ed.). The Rococo in England. London: Victoria and Albert Museum. pp. 46–59. ISBN 0-948107-37-5. OCLC 18588917.

- Rosenberg, Pierre; Prat, Louis-Antoine (1996). Antoine Watteau: catalogue raisonné des dessins (in French). Paris: Gallimard-Electa. ISBN 2070150437. OCLC 463981169.

- Schéfer, Gaston (September 1896). "Les Portraits dans l'oeuvre de Watteau". Gazette des Beaux-Arts (in French) (471): 177–189 – via Gallica.

- Schmidt-Linsenhoff, Viktoria (2008). "Ethnizität ist Maskerade. Eine postkoloniale Bildlektüre von Antoine Watteaus «Les Coquettes»". In Werner, Gabriele; Putz-Precko, Barbara (eds.). Asymmetrien. Festschrift für Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat zum 60. Geburtstag (in German). Wien: Eigenverlag. pp. 83–90. ISBN 3852111471. OCLC 489087049.

- Schubert, Rudolf E. (2000). "Unter dem Eindruck Flanderns: Beobachtungen zu den Inspirationsquellen und der Arbeitsweise Johann Georg Plazers" [Under the Impression of Flanders: Observations on the Sources of Inspiration and Working Methods of Johann Georg Plazer]. Belvedere: Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst. 6: 40–49, 83–87. ISSN 1025-2223.

- Shvartsman, N. A. (2013). Грёзы и миражи в садах Версаля [Dreams and Mirages in the Gardens of Versailles] (in Russian). Moscow: Belyi gorod. ISBN 978-5-7793-4400-5.

- Sterling, Charles (1957). Musée de l'Ermitage: la peinture française de Poussin à nos jours (in French). Paris: Cercle d'Art. p. 41, pl. 29. OCLC 411034675. Published in English as Great French Painting in the Hermitage. Translated by Christopher Ligota. New York: Harry N. Abrams. 1958. p. 41, pl. 29. OCLC 598217.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Stuffmann, Margret (July–September 1968). "Les tableaux de la collection de Pierre Crozat : historique et destinée d'un ensemble célèbre établis en partant d'un inventaire après décès inédit 30 mai 1740". Gazette des Beaux-Arts (in French). 72: 11–144. OCLC 888303109.

- Temperini, Renaud (2002). Watteau. Maîtres de l'art (in French). Paris: Gallimard. pp. 79, 145; cat. no. 77. ISBN 9782070116867. OCLC 300225840.

- Trauth, Nina. Maske und Person: Orientalismus im Porträt des Barock (in German). Berlin, München: Deutscher Kunstverlag. pp. 84, 394, ill. 45, cat. no. 452. ISBN 978-3-422-06859-9. OCLC 762789571.

- Troubnikoff, Alexander (July–September 1916). "Французская школа в Гатчинском дворце (La peinture française au château de Gatchina)" [French Painting in the Gatchina Palace]. Старые годы (in Russian). pp. 49–67.

- Troubnikoff, Alexander (September 1919). "La peinture française au palais de Gatchina". La Renaissance de l'art français et des industries de luxe. pp. 393–400 – via Gallica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vidal, Mary (1992). Watteau's Painted Conversations: Art, Literature, and Talk in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century France. New Haven, London: Yale University Press. pp. 146–147, fig. 142. ISBN 0-300-05480-7. OCLC 260176725.

- Weiner, P. P. von, ed. (1923). Meisterwerke der Gemäldesammlung in der Eremitage zu Petrograd (in German). München: F. Hanfstaengl. p. 15. OCLC 741513217 – via the Internet Archive.

- Zeri, Federico (2000) [first published in Italian in 1998]. Watteau: The Embarkment for Cythera. One Hundred Paintings. Richmond Hill, Ontario: NDE Pub. pp. 26, 45, 48. ISBN 1553210182. OCLC 48003550 – via the Internet Archive.

- Zolotov, Y. K. (1968). Французский портрет XVIII века [French Portrait in the Eighteenth Century]. Moscow: Iskusstvo. pp. 28, 30. OCLC 567935709.

- Zolotov, Y. K., ed. (1973). Антуан Ватто [Antoine Watteau] (album and catalogue) (in Russian). Leningrad: Aurora. pp. 138–140, cat. no. 6. OCLC 46947007.

- Zolotov, Yuri (November 1984). "Ватто: художественная традиция и творческая индивидуальность". Iskusstvo (in Russian). pp. 58–66. ISSN 0130-2523.

- Zolotov, Yuri, ed. (1985). Antoine Watteau: Paintings and Drawings from Soviet Museums. Translated from the Russian by Vladimir Pozner. Leningrad: Aurora Publishers. pp. 8, 11, 98–100, ill. 8–11. OCLC 249485317.

- Zolotov, Yuri, ed. (1996). Antoine Watteau: The Master of "Les Fêtes Galantes". Great Painters. English translation by Josephine Bacon. Bournemouth, St. Petersburg: Parkstone Press, Aurora Art Publishers. pp. 86–95, cat. no. 3. ISBN 185995183X. OCLC 37478254.

External links

- Actors of the Comédie-Française at the Hermitage's official website

- Actors of the Comédie-Française at the Web Gallery of Art