Adagia

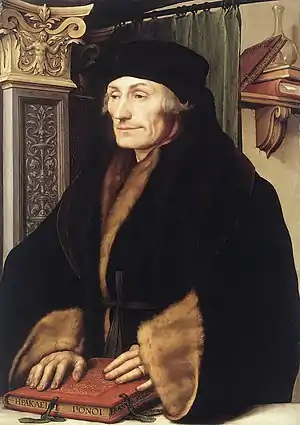

Adagia (singular adagium) is the title of an annotated collection of Greek and Latin proverbs, compiled during the Renaissance by Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus. Erasmus' collection of proverbs is "one of the most monumental ... ever assembled" (Speroni, 1964, p. 1).

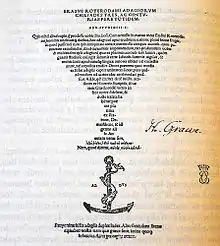

The first edition, titled Collectanea Adagiorum, was published in Paris in 1500, in a slim quarto of around eight hundred entries. By 1508, after his stay in Italy, Erasmus had expanded the collection (now called Adagiorum chiliades tres or "Three thousands of proverbs") to over 3,000 items, many accompanied by richly annotated commentaries, some of which were brief essays on political and moral topics. The work continued to expand right up to the author's death in 1536 (to a final total of 4,151 entries), confirming the fruit of Erasmus' vast reading in ancient literature.

Commonplace examples from Adagia

Some of the adages have become commonplace in many European languages. Equivalents in English include:

|

|

Context

The work reflects a typical Renaissance attitude toward classical texts: to wit, that they were fit for appropriation and amplification, as expressions of a timeless wisdom first uncovered by the classical authors. It is also an expression of the contemporary humanism; the Adagia could only have happened via the developing intellectual environment in which careful attention to a broader range of classical texts produced a much fuller picture of the literature of antiquity than had been possible, or desired, in medieval Europe. In a period in which sententiæ were often marked by special fonts and footnotes in printed texts, and in which the ability to use classical wisdom to bolster modern arguments was a critical part of scholarly and even political discourse, it is not surprising that Erasmus' Adagia was among the most popular volumes of the century.

Source: Erasmus, Desiderius. Adages in Collected Works of Erasmus. Trans. R.A.B Mynors et al. Volumes 31–36. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1982–2006. (A complete annotated translation into English. There is a one-volume selection: Erasmus, Desiderius. Adages. Ed. William Barker. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.)

References

- Eden, Kathy. Friends Hold All Things in Common: Tradition, Intellectual Property and the 'Adages' of Erasmus. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Greene, Thomas. The Light in Troy: Imitation and Discovery in Renaissance Poetry. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982.

- Hunter, G.K. "The Marking of Sententiæ in Elizabethan Printed Plays, Poems, and Romances." The Library 5th series 6 (1951): 171–188.

- McConica, James K. Past Masters: Erasmus. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Phillips, Margaret Mann. The Adages of Erasmus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964.

- Saladin, Jean-Christophe, ed. (2011). Érasme de Rotterdam: Les Adages (in French). Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-34605-2.

- Speroni, Charles. (1964). Wit and wisdom of the Italian Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964.

External links

- Erasmi Roterodami Adagiorum Chiliades Tres. Venice, 1508 Digital Edition

- Erasmi Roterodami Germaniae decoris Adagiorum chiliades tres. Basel, 1513 Digital Edition

- Adagia, complete Latin text online Base text used for the 2011 Belles Lettres translation in French.

- Adagia, complete Latin text online Searchable text from the nine-part volume II of the ASD Opera omnia, with full annotations and commentary. The actual volumes are available as scans from Open Access.

- Adagia, complete Latin text Scan of volume II of the Leiden Opera omnia of 1703-6.

- List of the proverbs From the 1703 Leiden Opera omnia, Leiden University.

- Proverbs taken chiefly from the Adagia (1814) explained and freely downloadable through the Internet Archive.

- Suringar, W. H. D., Erasmus over nederlandsche spreekworden (Utrecht 1873): An extraordinary and formerly hard-to-find compilation that identifies Erasmus' proverbs in many 16th-century vernacular proverb collections.