Aetolia

Aetolia (Greek: Αἰτωλία, romanized: Aἰtōlía) is a mountainous region of Greece on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, forming the eastern part of the modern regional unit of Aetolia-Acarnania.

Aetolia

Αἰτωλία | |

|---|---|

Region of Ancient Greece | |

Ancient and modern Thermon, Aetolia | |

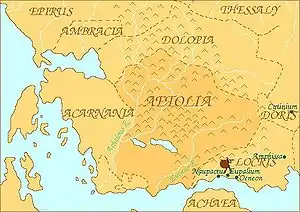

Map of ancient Aetolia | |

| Location | Western Greece |

| Major cities | Thermon |

| Dialects | Doric |

| Key periods | Aetolian League (290–189 BC) |

Geography

The Achelous River separates Aetolia from Acarnania to the west; on the north it had boundaries with Epirus and Thessaly; on the east with the Ozolian Locrians; and on the south the entrance to the Corinthian Gulf defined the limits of Aetolia.

In classical times Aetolia comprised two parts: "Old Aetolia" (Greek: Παλιά Αιτωλία, romanized: Paliá Aitolía) in the west, from the Achelous to the Evenus and Calydon; and "New Aetolia" (Greek: Νέα Αιτωλία, romanized: Néa Aitolía) or "Acquired Aetolia" (Greek: Αἰτωλία Ἐπίκτητος, romanized: Aitolía Epíktitos) in the east, from the Evenus and Calydon to the Ozolian Locrians. The country has a level and fruitful coastal region, but an unproductive and mountainous interior. The mountains contained many wild beasts, and acquired fame in Greek mythology as the scene of the hunt for the Calydonian Boar.

History

Ancient era

Tribes known as Curetes – named after the nearby mountain Kourion, or just to stand out from the Acarnanians, who were called so because they were unshorn – and Leleges originally inhabited the country, but at an early period Greeks from Elis, led by the mythical eponym Aetolus, set up colonies. Dionysius of Halicarnassus mentions that Curetes was the old name of the Aetolians and Leleges the old name of the Locrians.[1] The Aetolians took part in the Trojan War, under their king Thoas.

The mountain tribes of Aetolia were the Ophioneis,[2] the Apodotoi,[2] the Agraeis, the Aperantoi[3] and the Eurytanians.[2][4]

The primitive lifestyle of those tribes made an impression on ancient historians. Polybius doubted their Greek heritage, while Livy reports that they spoke a language similar to the Macedonians. On the other hand, Thucydides claims that Eurytanians spoke a very difficult language and ate their food completely raw. They were semi-barbaric, warlike and predatory. They worshiped Apollo as god of tame nature and Artemis as goddess of wilderness. They also worshiped Athena, not as goddess of wisdom, but emphasizing the element of war – i.e. a goddess that was a counterbalance to the god Ares. They called Apollo and Artemis "Laphrios gods," i.e. patrons of the spoils and loot of war. In addition, they worshiped Hercules, the river Achelous and Bacchus. In Thermos, an area north of Trichonis lake, there was after the 7th century a shrine of Apollo “Thermios,” which became a significant religious center during the time of the Aetolian League.

The Aetolians refused to participate in the Persian Wars. In 426 BC, led by Aegitios, they defeated the Athenians and their allies, who had turned against Apodotia and Ophioneia under the general command of Demosthenes.[5] However, they failed to regain Naupaktos, which had meanwhile been conquered by the Corinthians with the aid of the Athenians. At the end of the Peloponnesian War, the Aetolians took part as mercenaries of the Athenians in the expedition against Syracuse. Then the Achaeans occupied Calydon, but the Aetolians recovered it in 361 BC. In 338 BC, Naupaktos was again taken by the Aetolians, with the help of Philip II. During the Lamian War, the Aetolians helped the Athenian general Leosthenes defeat Antipater. As a result, they came into conflict with Antipater and Craterus, taking great risks, but were eventually saved by the disagreement between the two Macedonian generals and Perdiccas. The Acarnanians then attempted to invade their land, but the Aetolians were able to force them to flee.

The Aetolians set up a united league, the Aetolian League, in early times. It soon became a powerful confederation (sympoliteia) and by c. 340 BC it became one of the leading military powers in ancient Greece.[6] It had originally been organized during the reign of Philip II by the cities of Aetolia for their mutual benefit and protection and became a formidable rival to the Macedonian monarchs and the Achaean League.

The great courage shown by the Aetolians during the fighting against the Macedonians increased their glamour and fame, especially after winning the last Amphictyonic war and even more after repulsing the Gallic invasion under Brennus and rescuing the sanctuary of Delphi. Subsequently, the Sotiria Games were established by the Aetolians, in honour of Zeus the Saviour.[6][7]

The Aetolians’ power increasingly magnified with the occupation of the lands of Ozoloi, Locrians and Phocians, as well as Boeotia. They then united under the power of their League in the areas of Tegea, Mantinea, Orchomenus, Psophida and Phigaleia. Between 220–217 BC, the Social War broke out between the Achaean and Aetolian Leagues. The war was first started by the Aetolians with the help of the Spartans and Eleans. Allies of the Achaeans were the Macedonians, the Boeotians, the Phocians, the Epirotes, the Acarnanians and the Messenians.

The Aetolians allied with the Romans, while Philip destroyed the temple of Apollo Thermios and allied with the Carthaginians. The Aetolians continued to fight on the side of the Romans even in the Battle of Cynoscephalae (196 BC), ignoring the great dangers looming for Greece as a result of this alliance. The Aetolians took the side of Antiochus III against the Roman Republic, and on the defeat of that monarch in 189 BC, they became virtually the subjects of Rome. Following the conquest of the Achaeans by Lucius Mummius Achaicus in 146 BC, Aetolia became part of the Roman province of Achaea. When the Roman garrisons were withdrawn because of the civil wars in Rome, the Aetolians, too, began to fight each other. Following Octavius’ victory at the Battle of Actium, the Aetolians who had sided with Antony disbanded completely. Octavius handed Calydon over to the Achaeans, who devastated it entirely and moved the statue of Artemis Laphria to Patras. There were subsequent invasions by Goths, Huns, and Vandals several centuries later at the end of the Roman Empire.

Aetolia's reputation has suffered from a rather hostile treatment in the sources. Polybius is considered now to have a heavy anti-Aetolian bias due to his having relied on Aetolia's opponent Aratus of Achaea, but mainly because of his origin in Megalopolis, a major centre of the rival Achaean League.

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, Aetolia was part of the Byzantine Empire and later passed to the Turks. Aetolia was mentioned in Francisco Baltazar's Florante at Laura.

List of Aetolians

- Agetas, general [8]

- Aitolos, mythological hero

- Leda, Queen of Sparta and mother of Helen, Clytemnestra, and the Dioscuri by Zeus and Tyndareus

- Andraemon, father of Thoas

- Thoas, hero of the Trojan War

- Titormus, wrestler

- Alexander Aetolus, poet

- Damocritus, general

- Dorimachus, general [9]

- Nicolaus of Aetolia, general

- Theodotus of Aetolia, general

- Pyrrhias, stadion Olympic racer in 200 BC [10]

- Pyrrhias of Aetolia, general [11]

- Agelaus of Naupactus, leading man of the Aetolian League

- Cosmas of Aetolia, (1714–1779) monk

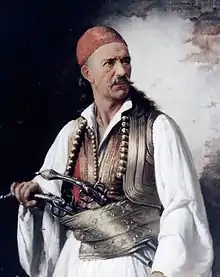

- Dimitrios Makris, fighter of the Greek War of Independence (1821)

See also

- Aetolian League

- List of traditional Greek place names

- Aetolia Game

References

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, Book 1, 1, LacusCurtius

- John D. Grainger, The League of the Aitolians, 1999, p. 33.

- John D. Grainger, The League of the Aitolians, 1999, p. 40.

- "Technological Educational Institute of Piraeus - Γενικά Στοιχεία". Archived from the original on 2015-04-03. Retrieved 2015-04-02.

- Istoriai, Thoucydides pages 243-246.

- "Aetolian League". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2010-09-10.

Aetolian League, federal state or “sympolity” of Aetolia, in ancient Greece. Probably based on a looser tribal community, it was well-enough organized to conduct negotiations with Athens in 367 BC. It became by c. 340 one of the leading military powers in Greece. Having successfully resisted invasions by Macedonia in 322 and 314–311, the league rapidly grew in strength during the ensuing period of Macedonian weakness, expanding into Delphi (centre of the Amphictyonic Council) and allying with Boeotia (c. 300). It was mainly responsible for driving out a major Gallic invasion of Greece in 279.

- John D. Grainger, The League of the Aitolians, 1999, p. 103 - 104.

- Smith, William (1867). "Agetas". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 71.

- "Smith Bio". Archived from the original on 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- Chronicon (Eusebius) 145th Olympiad

- Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology Pyrrhias Archived May 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- This article incorporates material from Harry Thurston Peck's Harper's Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898).