Epirus

Epirus (/ɪˈpaɪrəs/) is a geographical and historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay of Vlorë and the Acroceraunian Mountains in the north to the Ambracian Gulf and the ruined Roman city of Nicopolis in the south.[1][2] It is currently divided between the region of Epirus in northwestern Greece and the counties of Gjirokastër, Vlorë, and Berat in southern Albania. The largest city in Epirus is Ioannina, seat of the region of Epirus, with Gjirokastër the largest city in the Albanian part of Epirus.[1]

Epirus

| |

|---|---|

Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich Kiepert, 1902 | |

| Present status | Divided between Greece and Albania |

| Demonym(s) | Epirote |

| Time zones | Central European Time |

| Eastern European Time | |

A rugged and mountainous region, Epirus was the north-west area of ancient Greece.[2] It was inhabited by the Greek tribes of the Chaonians, Molossians, and Thesprotians. It was home to the sanctuary of Dodona, the oldest oracle in ancient Greece, and the second most prestigious after Delphi. Unified into a single state in 370 BC by the Aeacidae dynasty, Epirus achieved fame during the reign of Pyrrhus of Epirus who fought the Roman Republic in a series of campaigns. Epirus subsequently became part of the Roman Republic along with the rest of Greece in 146 BC, which was followed by the Roman Empire and Eastern Roman Empire.

Following the fall of Constantinople to the Fourth Crusade, Epirus became the center of the Despotate of Epirus, one of the successor states to the Byzantine Empire. Conquered by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century, Epirus became semi-independent during the rule of Ali Pasha in the early 19th century, but the Ottomans re-asserted their control in 1821. Following the Balkan Wars and World War I, southern Epirus became part of Greece, while northern Epirus became part of Albania.

Name and etymology

The name Epirus is derived from the Greek: Ἤπειρος, romanized: Ḗpeiros (Doric Greek: Ἄπειρος, romanized: Ápeiros), meaning "mainland" or terra firma.[3][4] It is thought to come from an Indo-European root *apero- 'coast',[5] and was originally applied to the mainland opposite Corfu and the Ionian islands.[6] The local name was struck on the coinage of the unified Epirote commonwealth: "ΑΠΕΙΡΩΤΑΝ" (Ancient Greek: Ἀπειρωτᾶν, romanized: Āpeirōtân, Attic Greek: Ἠπειρωτῶν, romanized: Ēpeirōtôn, i.e. "of the Epirotes", see image right). The Albanian name for the region, which derives from the Greek, is Epiri.(translated as drunken in English, water absorbed by land).

Boundaries and definitions

The historical region of Epirus is generally regarded as extending from the northern end of the Ceraunian mountains (modern Llogara in Albania), located just south of the Bay of Aulon (modern Vlorë), to the Ambracian Gulf (or Gulf of Arta) in Greece.[7] The northern boundary of ancient Epirus is alternatively given as the mouth of the Aoös (or Vjosë) river, immediately to the north of the Bay of Vlorë.[8] Epirus's eastern boundary is defined by the Pindus Mountains, that form the spine of mainland Greece and separate Epirus from Macedonia and Thessaly.[1] To the west, Epirus faces the Ionian Sea. The island of Corfu is situated off the Epirote coast but is not regarded as part of Epirus.

The definition of Epirus has changed over time, such that modern administrative boundaries do not correspond to the boundaries of ancient Epirus. The region of Epirus in Greece only comprises a fraction of classical Epirus and does not include its easternmost portions, which lie in Thessaly. In Albania, where the concept of Epirus is never used in an official context, the counties of Gjirokastër, Vlorë, and Berat extend well beyond the northern and northeastern boundaries of classical Epirus.

Geography and ecology

Epirus is a predominantly rugged and mountainous region. It is largely made up of the Pindus Mountains, a series of parallel limestone ridges that are a continuation of the Dinaric Alps.[1][9] The Pindus mountains form the spine of mainland Greece and separate Epirus from Macedonia and Thessaly to the east. The ridges of the Pindus are parallel to the sea and generally so steep that the valleys between them are mostly suitable for pasture rather than large-scale agriculture.[1] Altitude increases as one moves east, away from the coast, reaching a maximum of 2,637 m at Mount Smolikas, the highest point in Epirus. Other important ranges include Tymfi (2,496 m at Mount Gamila), Lygkos (2,249 m), to the west and east of Smolikas respectively, Gramos (2,523 m) in the northeast, Tzoumerka (2,356 m) in the southeast, Tomaros (1,976 m) in the southwest, Mitsikeli near Ioannina (1,810 m), Mourgana (1,806 m) and Nemercke/Aeoropos (2,485 m) on the border between Greece and Albania, and the Ceraunian Mountains (2,000 m) near Himara in Albania. Most of Epirus lies on the windward side of the Pindus, and the prevailing winds from the Ionian Sea make the region the rainiest in mainland Greece.[1]

Significant lowlands are to be found only near the coast, in the southwest near Arta and Preveza, in the Acheron plain between Paramythia and Fanari, between Igoumenitsa and Sagiada, and also near Saranda. The Zagori area is a scenic upland plateau surrounded by mountain on all sides.

The main river flowing through Epirus is the Vjosë (Aoös in Greek), which flows in a northwesterly direction from the Pindus mountains in Greece to its mouth north of the Bay of Vlorë in Albania. Other important rivers include the Acheron river, famous for its religious significance in ancient Greece and site of the Necromanteion, the Arachthos river, crossed by the historic Bridge of Arta, the Louros, the Thyamis or Kalamas, and the Voidomatis, a tributary of the Vjosë flowing through the Vikos Gorge. The Vikos Gorge, one of the deepest in the world, forms the centerpiece of the Vikos–Aoös National Park, known for its scenic beauty. The only significant lake in Epirus is Lake Pamvotis, on whose shores lies the city of Ioannina, the region's largest and traditionally most important city.

The climate of Epirus is Mediterranean along the coast and Alpine in the interior. Epirus is heavily forested, mainly by coniferous species. The fauna in Epirus is especially rich and features species such as bears, wolves, foxes, deer and lynxes.

History

Early history

Epirus has been occupied since at least Neolithic times by seafarers along the coast and by hunters and shepherds in the interior who brought with them the Greek language.[1] These people buried their leaders in large tumuli containing shaft graves, similar to the Mycenaean tombs, indicating an ancestral link between Epirus and the Mycenaean civilization.[1] A number of Mycenaean remains have been found in Epirus,[10] especially at the most important ancient religious sites in the region, the Necromanteion (Oracle of the Dead) on the Acheron river, and the Oracle of Zeus at Dodona.[1]

In the Middle Bronze Age, Epirus was inhabited by the same nomadic Hellenic tribes that went on to settle in the rest of Greece.[11] Aristotle considered the region around Dodona to have been part of Hellas and the region where the Hellenes originated.[12][13] According to Bulgarian linguist Vladimir I. Georgiev, Epirus was part of the Proto-Greek linguistic area during the Late Neolithic period.[14] By the early 1st millennium BC, all fourteen Epirote tribes including the Chaonians in northwestern Epirus, the Molossians in the centre and the Thesprotians in the south, were speakers of a strong west Greek dialect.[1][2][15]

Epirus in the Classical and Hellenistic periods

.svg.png.webp)

Geographically on the edge of the Greek world, Epirus remained for the most part outside the limelight of Greek history until relatively late, much like the neighbouring Greek regions of Macedonia, Aetolia, and Acarnania, with which Epirus had political, cultural, linguistic and economic connections. Unlike most other Greeks of this time, who lived in or around city-states, the inhabitants of Epirus lived in small villages and their way of life was foreign to that of the poleis of southern Greece.[1][17] Their region lay on the periphery of the Greek world[1] and was far from peaceful; for many centuries, it remained a frontier area contested with the Illyrian peoples to the north. However, Epirus had a far greater religious significance than might have been expected given its geographical remoteness, due to the presence of the shrine and oracle at Dodona – regarded as second only to the more famous oracle at Delphi.

The Epirotes, speakers of a Northwest Greek dialect, different from the Dorian of the Greek colonies on the Ionian islands, and bearers of mostly Greek names, as evidenced by epigraphy, seem to have been regarded with some disdain by some classical writers. The 5th-century BC Athenian historian Thucydides describes them as "barbarians" in his History of the Peloponnesian War,[18] as does Strabo in his Geography.[19] Other writers, such as Herodotus,[20] Dionysius of Halicarnassus,[21] Pausanias,[22] and Eutropius,[23] describe them as Greeks. Similarly, Epirote tribes/states are included in the Argive and Epidaurian lists of the Greek Thearodokoi (hosts of sacred envoys).[24] Plutarch mentions an interesting element of Epirote folklore regarding Achilles: In his biography of King Pyrrhus, he claims that Achilles "had a divine status in Epirus and in the local dialect he was called Aspetos" (meaning unspeakable, unspeakably great, in Homeric Greek).[25][26]

Beginning in 370 BC, the Molossian Aeacidae dynasty built a centralized state in Epirus and began expanding their power at the expense of rival tribes.[1] The Aeacids allied themselves with the increasingly powerful kingdom of Macedon, in part against the common threat of Illyrian raids,[27] and in 359 BC the Molossian princess Olympias, niece of Arybbas of Epirus, married King Philip II of Macedon.[1] She was to become the mother of Alexander the Great.

On the death of Arybbas, Alexander of Epirus succeeded to the throne and the title King of Epirus in 334 BC. He invaded Italy, but was killed in battle by a Lucanian in the Battle of Pandosia against several Italic tribes 331 BC.[1][28] Aeacides of Epirus, who succeeded Alexander, espoused the cause of Olympias against Cassander, but was dethroned in 313 BC. His son Pyrrhus came to throne in 295 BC, and for six years fought against the Romans and Carthaginians in southern Italy and Sicily. The high cost of his victories against the Romans gave Epirus a new, but brief, importance, as well as a lasting contribution to the Greek language with the concept of a "Pyrrhic victory". Pyrrhus nonetheless brought great prosperity to Epirus, building the great theater of Dodona and a new suburb at Ambracia (now modern Arta), which he made his capital.[1]

The Aeacid dynasty ended in 232 BC, but Epirus remained a substantial power, unified under the auspices of the Epirote League as a federal state with its own parliament, or synedrion.[1] However, it was faced with the growing threat of the expansionist Roman Republic, which fought a series of wars against Macedon. The League steered an uneasy neutral course in the first two Macedonian Wars but split in the Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC), with the Molossians siding with the Macedonians and the Chaonians and Thesprotians siding with Rome.[1] The outcome was disastrous for Epirus; Molossia fell to Rome in 167 BC and 150,000 of its inhabitants were enslaved.[1]

Epirus as a Roman province

The region of Epirus was placed under the senatorial province of Achaea in 27 BC, with the exception of its northernmost part, which remained part of the province of Macedonia.[29] Under Emperor Trajan, sometime between 103 and 114 AD, Epirus became a separate province, under a procurator Augusti. The new province extended from the Gulf of Aulon (Vlorë) and the Acroceraunian Mountains in the north to the lower course of the Acheloos River in the south, and included the northern Ionian Islands of Corfu, Lefkada, Ithaca, Cephallonia, and Zakynthos.[29]

Late Antiquity

.svg.png.webp)

Probably during the provincial reorganization by Diocletian (r. 284–305), the western portion of the province of Macedonia along the Adriatic coast was split off into the province of New Epirus (Latin: Epirus Nova). Although this territory was not traditionally part of Epirus proper as defined by the ancient geographers, and was historically inhabited predominantly by Illyrian tribes, the name reflects the fact that under Roman rule, the area had been subject to increasing Hellenization and settlement by Epirote tribes from the south.[29]

The two Epirote provinces became part of the Diocese of Moesia, until it was divided in ca. 369 into the dioceses of Macedonia and Dacia, when they became part of the former.[30] In the 4th century, Epirus was still a stronghold of paganism, and was aided by Emperor Julian (r. 361–363) and his praetorian prefect Claudius Mamertinus through reduction in taxes and the rebuilding of the provincial capital, Nicopolis.[31] According to Jordanes, in 380 the Visigoths raided the area.[31] With the division of the Empire on the death of Theodosius I in 395, Epirus became part of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire.[31] In 395–397, the Visigoths under Alaric plundered Greece. They remained in Epirus for a few years, until 401, and again in 406–407, during Alaric's alliance with the Western Roman generalissimo Stilicho in order to wrest the Eastern Illyricum from the Eastern Empire.[31]

The Synecdemus of Hierocles, composed in ca. 527/8 AD but probably reflecting the situation in the first half of the 5th century, reports 11 cities for Old Epirus (Ancient Greek: Παλαιὰ Ἤπειρος, Latin: Epirus Vetus): the capital Nicopolis, Dodona, Euroea, Hadrianopolis, Appon, Phoenice, Anchiasmos, Buthrotum, Photike, Corfu Island, and Ithaca Island.[32] New Epirus, with capital at Dyrrhachium, comprised 9 cities.[31] From 467 on, the Ionian Islands and the coasts of Epirus became subject to raids by the Vandals, who had taken over the North African provinces and established their own kingdom centred on Carthage. The Vandals notably seized Nicopolis in 474 as a bargaining chip in their negotiations with Emperor Zeno, and plundered Zakynthos, killing many of its inhabitants and ferrying off others into slavery.[33] Epirus Nova became a battleground in the rebellions of the Ostrogoths after 479.[33] In 517, a raid of the Getae or Antae reached Greece, including Epirus Vetus.[33] The claim of Procopius of Caesarea in his Secret History, that under Justinian I (r. 527–565) the entirety of the Balkan provinces was raided by barbarians every year, is considered rhetorical hyperbole by modern scholars; only a single Slavic raid to the environs of Dyrrhachium, in 548/9, has been documented.[33] Procopius further reports that in 551, in an attempt to interdict the Byzantines' lines of communication with Italy during the Gothic War, the Ostrogoth king Totila sent his fleet to raid the shores of Epirus.[34] In response to these raids, and to repair the damage done by two destructive earthquakes in 522, Justinian initiated a wide-ranging programme of reconstruction and re-fortification: Hadrianopolis was rebuilt, albeit in reduced extent, and renamed Justinianopolis, while Euroea was moved further inland (traditionally identified with the founding of Ioannina), while Procopius claims that no less than 36 smaller fortresses in Epirus Vetus—most of them not identifiable today—were either rebuilt or built anew.[34]

Epirus from the Slavic invasions until 1204

In the late 6th century, much of Greece, including Epirus, fell under the control of the Avars and their Slavic allies. This is placed by the Chronicle of Monemvasia in the year 587, and is further corroborated by evidence that several sees were abandoned by their bishops by 591. Thus in c. 590 the bishop, clergy and people of Euroea fled their city, carrying with them the relics of their patron saint, St. Donatus, to Cassiope in Corfu.[35]

Of the various Slavic tribes, only the Baiounitai, first attested c. 615, are known by name, giving their name to their region of settlement: "Vagenetia".[35] Based on the density of the Slavic toponyms in Epirus, the Slavs must have settled in the region, although the extent of this settlement is unclear.[36] Slavic toponyms occur mainly in the mountainous areas of the interior and the coasts of the Gulf of Corinth, indicative of the fact that this was the avenue used by most of the Slavs who crossed the Gulf into the Peloponnese. With the exception of some few toponyms on Corfu, the Ionian Islands seem to not have been affected by Slavic settlemet. The linguistic analysis of the toponyms reveals that they date mostly to the early wave of Slavic settlement at the turn of the 6th/7th centuries. Due to scarcity of textual evidence, it is unclear how much the area was affected by the second wave of Slavic migration, which began in the middle of the 8th century due to Bulgar pressure in the northern Balkans.[37]

As in eastern Greece, the restoration of Byzantine rule seems to have proceeded from the islands, chiefly Cephallonia, which was certainly under firm Imperial control in c. 702, when Philippicus Bardanes was banished there. The gradual restoration of Imperial rule is evidenced further from the participation of local bishops in councils in Constantinople: whereas only the bishop of Dyrrhachium participated in the Ecumenical Councils of 680/1 and 692, a century later the bishops of Dyrrhachium, Nicopolis, Corfu, Cephallonia, and Zakynthos are attested in the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.[38] In about the middle of the 8th century, the Theme of Cephallenia was established, but at least initially it was more oriented towards restoring Byzantine control over the Ionian and Adriatic seas, combating Saracen piracy, and securing communications with the remaining Byzantine possessions in Italy, rather than any systematic effort at subduing the Epirote mainland.[38] Nevertheless, following the onset of the Muslim conquest of Sicily in 827, the Ionian became particularly exposed to Arab raids.[39]

The 9th century saw great progress in the restoration of Imperial control in the mainland, as evidenced by the participation of the bishops of Ioannina, Naupaktos, Hadrianopolis, and Vagenetia (evidently by now organized as a Sklavinia under imperial rule) in the Ecumenical Councils of 869/70 and 879/80.[39] The Byzantine recovery resulted in an influx of Greeks from southern Italy and Asia Minor into the Greek interior, while remaining Slavs were Christianized and Hellenized.[40] The eventual success of the Hellenization campaign also suggests a continuity of the original Greek population, and that the Slavs had settled among many Greeks, in contrast to areas further north, in what is now Bulgaria and the former Yugoslavia, as those areas could not be Hellenized when they were recovered by the Byzantines in the early 11th century.[40] Following the great naval victory of admiral Nasar in 880, and the beginning of the Byzantine offensive against the Arabs in southern Italy in the 880s, the security situation improved and the Theme of Nicopolis was established, most likely after 886.[39][41] As the ancient capital of Epirus had been laid waste by the Slavs, the capital of the new theme became Naupaktos further south. The extent of the new province is unclear, but probably matched the extent of the Metropolis of Naupaktos, established at about the same time, encompassing the sees of Vonditsa, Aetos, Acheloos, Rogoi, Ioannina, Hadrianopolis, Photike, and Buthrotum. Vagenetia notably no longer appears as a bishopric. As the authors of the Tabula Imperii Byzantini comment, it appears that "the Byzantine administration had brought the strongly Slavic-settled areas in the mainland somewhat under its control, and a certain Re-Hellenization had set in".[42] Further north, the region around Dyrrhachium existed as the homonymous theme possibly as early as the 9th century.[43]

During the early 10th century, the themes of Cephallenia and Nicopolis appear mostly as bases for expeditions against southern Italy and Sicily, while Mardaites from both themes are listed in the large but unsuccessful expedition of 949 against the Emirate of Crete.[44] In c. 930, the Theme of Nicopolis was raided by the Bulgarians, who even occupied some parts until driven out or subjugated by the Byzantines years later.[44] Only the extreme north of Epirus seems to have remained consistently under Bulgarian rule in the period, but under Tsar Samuel, who moved the centre of Bulgarian power south and west to Ohrid, probably all of Epirus down to the Ambracian Gulf came under Bulgarian rule.[45] This is evidenced from the fact that the territories that were under Bulgarian rule formed part of the autocephalous Archbishopric of Ohrid after the Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria by Emperor Basil II in 1018: thus in Epirus the sees of Chimara, Hadrianopolis, Bela, Buthrotum, Ioannina, Kozyle, and Rogoi passed under the jurisdiction of Ohrid, while the Metropolitan of Naupaktos retained only the sees of Bonditza, Aetos, and Acheloos.[45] Basil II also established new, smaller themes in the region: Koloneia, and Dryinopolis (Hadrianopolis).[45]

The region joined the uprising of Petar Delyan in 1040, and suffered in the First Norman invasion of the Balkans: Dyrrhachium was occupied by the Normans in 1081–1084, Arta was unsuccessfully besieged, and Ioannina was captured by Robert Guiscard.[46] An Aromanian presence in Epirus is first mentioned in the late 11th century, while Jewish communities are attested throughout the medieval period in Arta and Ioannina.[47]

Epirus between 1204 and the Ottoman conquest

When Constantinople fell to the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the partitio Romaniae assigned Epirus to Venice, but the Venetians were largely unable to effectively establish their authority, except over Dyrrhachium (the "Duchy of Durazzo"). The Greek noble Michael Komnenos Doukas, who had married the daughter of a local magnate, took advantage of this, and within a few years consolidated his control over most of Epirus, first as a Venetian vassal and eventually as an independent ruler. By the time of his death in 1214/5, Michael had established a strong state, the Despotate of Epirus, with the former theme of Nicopolis at its core and Arta as its capital.[48][49] Epirus, and the city of Ioannina in particular, became a haven for Greek refugees from the Latin Empire of Constantinople for the next half-century.[49]

The Despotate of Epirus ruled over Epirus and western Greece as far south as Naupaktos and the Gulf of Corinth, much of Albania (including Dyrrhachium), Thessaly, and the western portion of Macedonia, extending its rule briefly over central Macedonia and most of Thrace following the aggressive expansionism of Theodore Komnenos Doukas, who established the Empire of Thessalonica in 1224.[50][51] During this time, the definition of Epirus came to encompass the entire coastal region from the Ambracian Gulf to Dyrrhachium, and the hinterland to the west up to the highest peaks of the Pindus mountain range. Some of the most important cities in Epirus, such as Gjirokastër (Argyrokastron), were founded during this period.[52] The oldest reference to Albanians in Epirus is from a Venetian document dating to 1210, which states that "the continent facing the island of Corfu is inhabited by Albanians", although a pre-14th century Albanian migration cannot be confirmed.[52] In 1337, Epirus was once again brought under the rule of the restored Byzantine Empire.[51]

In 1348, taking advantage of the civil war between the Byzantine emperors John V Palaiologos and John VI Kantakouzenos, the Serbian king Stefan Uroš IV Dušan conquered Epirus, with a number of Albanian mercenaries assisting him.[53] The Byzantine authorities in Constantinople soon re-established a measure of control by making the Despotate of Epirus a vassal state, but meanwhile Albanian clans invaded and seized most of the region. The Albanian Losha and Zenevisi clans founded two short-lived principalities, centered in Arta (1358–1416) and Gjirokastër (1386–1411) respectively. Only the city of Ioannina remained under Greek control during this time.[54] Although Albanian clans gained control of most of the region by 1366/7, their continued division into rival clans meant that they could not establish a single central authority.[55]

Ioannina became a center of Greek resistance to the Albanian clans. The Greeks of Ioannina offered power to three foreign rulers during this time, beginning with Thomas II Preljubović (1367–1384), followed by Esau de' Buondelmonti (1385–1411), and finally Carlo I Tocco (1411–1429). The latter finally succeeded in ending the rule of the Albanian clans and unifying Epirus under his rule.[56] Nevertheless, internal dissension eased the Ottoman conquest, which began with the capture of Ioannina in 1430 and continued with Arta in 1449, Angelokastro in 1460, Riniasa Castle and its environs (in what is now Preveza) in 1463,[57] and finally Vonitsa in 1479. With the exception of several coastal Venetian possessions, this was also the end of Latin rule in mainland Greece.

Ottoman rule

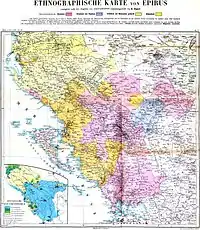

|

Greek speakers

Greek and Vlach speakers

Greek and Albanian speakers

Albanian speakers |

Greek Orthodox entirely

Greek Orthodox majority

Greek Orthodox – Muslim equivalence

Muslim majority

Muslim entirely |

Epirus was ruled by the Ottomans for almost 500 years. Ottoman rule in Epirus proved particularly damaging; the region was subjected to deforestation and excessive cultivation, which damaged the soil and drove many Epirotes to emigrate so as to escape the region's pervasive poverty.[1] Nonetheless, the Ottomans did not enjoy total control of Epirus. The Himara and Zagori regions managed to successfully resist Ottoman rule and maintained a degree of independence throughout this period. The Ottomans expelled the Venetians from almost the whole area in the late 15th century.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, the city of Ioannina attained great prosperity and became a major center of the modern Greek Enlightenment.[58][59][60][61] Numerous schools were founded, such as the Balaneios, Maroutsaia, Kaplaneios, and Zosimaia, teaching subjects such as literature, philosophy, mathematics and physical sciences. In the 18th century, as the power of the Ottoman Empire declined, Epirus became a de facto independent region under the despotic rule of Ali Pasha of Tepelena, a Muslim Albanian brigand who rose to become the provincial governor of Ioannina in 1788.[1] At the height of his power, he controlled all of Epirus, and much of the Peloponnese, central Greece, and parts of western Macedonia[1] Ali Pasha's campaign to subjugate the confederation of the settlements of Souli met with fierce resistance by the Souliot warriors of the mountainous area. After numerous failed attempts to defeat the Souliotes, his troops succeeded in conquering the area in 1803. On the other hand, Ali, who used Greek as official language, witnessed an increase of Greek cultural activity with the establishment of several educational institutions.[62]

When the Greek War of Independence broke out, the inhabitants of Epirus contributed greatly. Two of the founding members of the Filiki Eteria (the secret society of the Greek revolutionaries), Nikolaos Skoufas and Athanasios Tsakalov, came from the Arta area and the city of Ioannina, respectively. Greece's first constitutional prime minister (1844–1847), Ioannis Kolettis, was a native of the village of Syrrako in Epirus and was a former personal physician to Ali Pasha. Ali Pasha tried to use the war as an opportunity to make himself a fully independent ruler, but was assassinated by Ottoman agents in 1822. When Greece became independent in 1830, however, Epirus remained under Ottoman rule. In 1854, during the Crimean War, a major local rebellion broke out. Although the newly found Greek state tried tacitly to support it, the rebellion was suppressed by Ottoman forces after a few months.[63] Another failed rebellion by local Greeks broke out in 1878. During this period, the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople managed to shut down the few Albanian schools, considering teaching in Albanian a factor that would diminish its influence and lead to the creation of separate Albanian church, while publications in Albanian were banned by the Ottoman Empire.[64][65] In the late 19th century, the Kingdom of Italy opened various schools in the regions of Ioannina and Preveza in order to influence the local population. These schools began to attract students from the Greek language schools, but were ultimately closed after intervention and harassment by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[66] Throughout, the late period of Ottoman rule (from the 18th century) Greek and Aromanian population of the region suffered from Albanians raiders, that sporadically continued after Ali Pasha's death, until 1912–1913.[67]

20th-century Epirus

While the Treaty of Berlin (1878) awarded large parts of Epirus to Greece, opposition by the Ottomans and the League of Prizren resulted in only the region of Arta being ceded to Greece in 1881.[68] It was only following the First Balkan War of 1912–1913 and the Treaty of London that the rest of southern Epirus, including Ioannina, was incorporated into Greece.[69] Greece had also seized northern Epirus during the Balkan Wars, but the Treaty of Bucharest, which concluded the Second Balkan War, assigned Northern Epirus to Albania.[70]

This outcome was unpopular among local Greeks, as a substantial Greek population existed on the Albanian side of the border.[71] Among Greeks, northern Epirus was henceforth regarded as terra irredenta.[72] Local Greeks in northern Epirus revolted, declared their independence and proclaimed the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus in February 1914.[73] After fierce guerrilla fighting, they managed to gain full autonomy under the terms of the Protocol of Corfu, signed by Albanian and Northern Epirote representatives and approved by the Great Powers. The signing of the Protocol ensured that the region would have its own administration, recognized the rights of the local Greeks and provided self-government under nominal Albanian sovereignty.[74] The Republic, however, was short-lived, as when World War I broke out, Albania collapsed, and northern Epirus was alternately controlled by Greece, Italy and France at various intervals.[72][75] Although short-lived, this state managed to leave behind a number of historical records of its existence, including its own postage stamps; see Postage stamps and postal history of Epirus.[74]

Red dotted line: Territory of Autonomous State of Northern Epirus

Although the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded Northern Epirus to Greece, developments such as the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War and, crucially, Italian lobbying in favor of Albania meant that Greece would not keep Northern Epirus. In 1924, the area was again ceded to Albania.[77]

In 1939, Italy occupied Albania, and in 1940 invaded Greece. The Italians were driven back into Albania, however, and Greek forces again took control of northern Epirus. The conflict marked the first tactical victory of the Allies in World War II. Benito Mussolini himself supervised the massive counter-attack of his divisions in spring 1941, only to be decisively defeated again by the poorly equipped, but determined, Greeks. Nazi Germany then intervened in April 1941 to avert an embarrassing, wholesale Italian defeat. The German military performed rapid military maneuvers through Yugoslavia and forced the encircled Greek forces of the Epirus front to surrender.

The whole of Epirus was then placed under Italian occupation until 1943, when the Germans took over following the Italian surrender to the Allies. Due to the extensive activity of the anti-Nazi Greek resistance (mainly under EDES), the Germans carried out large scaled anti-partisan sweeps, making wide use of Nazi-collaborationist bands of Cham Albanians, who committed numerous atrocities against the civilian population.[78]

To deal with the situation, the Allied Military Mission in the Axis-occupied Greece (under Colonel C. M. Woodhouse), gave EDES partisans direct orders to counter-attack and chase out of their villages those units that used them as bases and local strongholds. Helped by Allied war material transferred from the recently liberated southern Italy, EDES forces succeeded and as a result several thousands of Muslim Cham Albanians fled the area and took refuge in nearby Albania.

With the liberation of Greece and the start of the first round of the Greek Civil War at the end of 1944, the highlands of Epirus became a major theater of guerrilla warfare between the leftist Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS) and the right-wing National Republican Greek League (EDES). In subsequent years (1945–1949), the mountains of Epirus also became the scene of some of the fiercest fighting of the second and bloodier round of the Greek Civil War. The final episode of the war took place on Mount Grammos in 1949, ending with the defeat of the Communists. Peace returned to the region in 1949, although because of official Albanian active involvement in the civil war on the side of the communists, the formal state of war between Greece and Albania remained in effect until 1987. Another reason for the continuation of the state of war until 1987 was that during the entire period of Communist rule in Albania, the Greek population of Northern Epirus experienced forced Albanisation.[79] Although a Greek minority was recognized by the Hoxha regime, this recognition only applied to an "official minority zone" consisting of 99 villages, leaving out important areas of Greek settlement, such as Himara.[72] People outside the official minority zone received no education in the Greek language, which was prohibited in public.[72] The Hoxha regime also diluted the ethnic demographics of the region by relocating Greeks living there and settling in their stead Albanians from other parts of the country.[72] Relations began to improve in the 1980s with Greece's abandonment of any territorial claims over Northern Epirus and the lifting of the official state of war between the two countries.[72]

The collapse of the communist regime in Albania in 1990–1991 triggered a massive migration of Albanian citizens to Greece, which included many members of the Greek minority. Since the end of the Cold War, many Greeks in Northern Epirus are re-discovering their Greek heritage thanks to the opening of Greek schools in the region, while Cham Albanians have called for compensation for their lost property. In the post-Cold War era, relations have continued to improve though tensions remain over the availability of education in the Greek language outside the official minority zone, the minority's property rights, and occasional violent incidents targeting members of the Greek minority.

Economy

A rugged topography, poor soils, and fragmented landholdings have kept agricultural production low and have resulted in a low population density.[1] Animal husbandry is the main industry and corn the chief crop.[1] Oranges and olives are grown in the western lowlands, while tobacco is grown around Ioannina.[1] Epirus has few natural resources and industries, and the population has been depleted by migration.[1] The population is centered around Ioannina, which has the largest number of industrial establishments.[1]

Transportation

Epirus has historically been a remote and isolated region due to its location between the Pindus mountains and the sea. In antiquity, the Roman Via Egnatia passed through Epirus Nova, which linked Byzantium and Thessalonica to Dyrrachium on the Adriatic Sea. The modern Egnatia Odos highway, which links Ioannina to the Greek province of Macedonia and terminating at Igoumenitsa, is the only highway through the Pindus mountains and has served to greatly reduce the region's isolation from the east, while the Ionia Odos highway, connecting Epirus with Western Greece, helped reducing the region's isolation from the south. Also, the Aktio-Preveza Undersea Tunnel connects the southernmost tip of Epirus, near Preveza, with Aetolia-Acarnania in western Greece. Ferry services from Igoumenitsa to the Ionian islands and Italy exist. The only airport in Epirus is the Ioannina National Airport, while the Aktion National Airport is located just south of Preveza in Aetolia-Acarnania. There are no railroads in Epirus.

Gallery

The Bridge of Arta.

The Bridge of Arta. The village of Aetomilitsa on Mount Gramos, in the Pindus mountains.

The village of Aetomilitsa on Mount Gramos, in the Pindus mountains. The Vikos river, Vikos–Aoös National Park.

The Vikos river, Vikos–Aoös National Park. The Vikos Gorge.

The Vikos Gorge.

The high altitude Lake Drakolimni (Dragon Lake), on Mount Gamila in the Pindus mountains.

The high altitude Lake Drakolimni (Dragon Lake), on Mount Gamila in the Pindus mountains. A canyon of the Acheron river.

A canyon of the Acheron river. The village of Sirako.

The village of Sirako. The walls of ancient Nicopolis.

The walls of ancient Nicopolis. The Hellenistic theater of Dodona.

The Hellenistic theater of Dodona. Sheep under the shade of a tree near Konitsa.

Sheep under the shade of a tree near Konitsa. The bay of Parga.

The bay of Parga. The region of Himara seen from the Llogara pass.

The region of Himara seen from the Llogara pass.

Section of the Egnatia Odos, the only freeway in Epirus, near Igoumenitsa.

Section of the Egnatia Odos, the only freeway in Epirus, near Igoumenitsa.

Preveza seen from the air.

Preveza seen from the air.

References

Citations

- "Epirus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Hornblower, Spawforth & Eidinow 2012, "Epirus", p. 527.

- Liddell & Scott 1940, ἤπειρ-ος.

- Filos 2018, p. 215, footnote #1.

- Babiniotis 1998.

- Winnifrith 2002, p. 22.

- Strabo. Geography, 7.7.5.

- Wilkes 1995, p. 92 "Appian's description of the Illyrian territories records a southern boundary with Chaonia and Thesprotia, where ancient Epirus began south of the river Aous (Vijosë)." (Map)

- Bahr, Johnston & Bloomfield 1997, p. 389.

- Tandy 2001, p. 4; McHenry 2003, p. 527: "Epirus itself remained culturally backward during this time, but Mycenean remains have been found at two religious shrines of great antiquity in the region: the Oracle of the Dead on the Acheron River, familiar to the heroes of Homer's Odyssey."

- Borza 1992, pp. 62, 78, 98; Minahan 2002, p. 578.

- Hammond 1986, p. 77: "The original home of the Hellenes was 'Hellas', the area round Dodona in Epirus, according to Aristotle. In the Iliad it was the home of Achilles' Hellenes."

- Aristotle. Meteorologica, 1.14: "Rather we must take the cause of all these changes to be that, just as winter occurs in the seasons of the year, so in determined periods there comes a great winter of a great year and with it excess of rain. But this excess does not always occur in the same place. The deluge in the time of Deucalion, for instance, took place chiefly in the Greek world and in it especially about ancient Hellas, the country about Dodona and the Achelous, a river which has often changed its course. Here the Selli dwelt and those who were formerly called Graeci and now Hellenes."

- Georgiev 1981, p. 192: "Late Neolithic Period: in northwestern Greece the Proto-Greek language had already been formed: this is the original home of the Greeks."

- Hammond 1998; Wilkes 1995, p. 104; Hammond 1994, pp. 430, 434; Hammond 1982, p. 284.

- Hammond 1967.

- Thucydides. The History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.8.

- Strabo. Geography, 7.7.1.

- Herodotus. Histories, 6.127.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Roman Antiquities, 20.10 (19.11).

- Pausanias. Description of Greece, 1.11.7–1.12.2.

- Eutropius. Abridgment of Roman History (Historiae Romanae Breviarium), 2.11.13.

- Davies 2002, pp. 234–258.

- Cameron 2004, p. 141: "As for Aspestos, Achilles was honored in Epirus under that name, and the patronymic [Ἀ]σπετίδης is found in a fragmentary poem found on papyrus."

- cf. Athenian secretary: Aspetos, son of Demostratos from Kytheros c. 340 BC.

- Anson 2010, p. 5.

- Livy (1926), 8.24.8–14

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 47.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 47–48.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 48.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 48–49.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 49.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 50.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 51.

- Osswald 2007, p. 128.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 51–52.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 52.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 53.

- Fine 1991, p. 64.

- Kazhdan 1991, p. 1485.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 53–54.

- Kazhdan 1991, p. 668.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 54.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 55.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 55–56.

- Osswald 2007, p. 129.

- Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 59–61.

- Osswald 2007, p. 132.

- Nicol 1984, "Introduction", pp. 4–5.

- Osswald 2007, p. 133.

- Giakoumis 2002, p. 176.

- Osswald 2007, p. 135.

- Osswald 2007, p. 134.

- Fine 1994, pp. 348–351.

- Osswald 2007, p. 136.

- Karabelas 2015, pp. 972–975.

- Sakellariou 1997, p. 268.

- Fleming 1999, pp. 63–66.

- The Era of Enlightenment (Late 7th century–1821). Eθνικό Kέντρο Bιβλίου, p. 13.

- Υπουργείο Εσωτερικών, Αποκέντρωσης και Ηλεκρονικής Διακυβέρνησης Περιφέρεια Ηπείρου: "Στη δεκαετία του 1790 ο νεοελληνικός διαφωτισμός έφθασε στο κορύφωμά του. Φορέας του πνεύματος στα Ιωάννινα είναι ο Αθανάσιος Ψαλίδας."

- Fleming 1999, p. 64.

- Reid 2000.

- Jelavich & Jelavich 1977, p. 226.

- Ramet 1998, p. 205.

- Blumi 2002, p. 57.

- Hammond 1976, p. 41: "Throughout this period bands of Albanians raiders pillaged and destroyed the villages of the Vlachs and the Greeks in Epirus, northern Pindus, the lakeland of Prespa and Ochrid, and parts of western Macedonia. One Albanian leader, 'Ali the Lion', emulated the achievements of 'John the Sword' and 'Peter the Pockmark' when he established himself as Ali Pasha, independent ruler of Ioannina. He and his Albanian soldiers, recruited mainly from his homeland in the Kurvelesh and the Drin valley of North Epirus, controlled the whole of Epirus and carried their raids far into western Macedonia and Thessaly. As we have seen, they destroyed the Vlach settlements in the lakeland and weakened those farther south. After the assassination of Ali Pasha in 1822 sporadic raids by bands of Albanians were a feature of life in northern Greece until the liberation of 1912–13.".

- Gawrych 2006, pp. 68–69.

- Clogg 2002, p. 105: "In February 1913 the Greek Army seized Ioannina, the capital of Epirus. The Turks recognized the gains of the Balkan allies by the Treaty of London, in May 1913."

- Clogg 2002, p. 105 "The Second Balkan War had short duration and the Bulgarians were soon dragged to the table of negotiations. By the Treaty of Bucharest (August 1913) Bulgaria was forced to accept a little favourable regulation of the borders, even if she kept a way to the Aegean, in Degeagatch (modern Alexandroupolis). The sovereignty of Greece over Crete was now recognised, but her ambition to annex Northern Epirus with its large Greek population was stopped by the annexation of the area to an independent Albania.".

- Pettifer 2001, p. 4.

- Konidaris 2005, pp. 64–92.

- Winnifrith 2002, p. 130.

- Stickney 1926.

- Tucker & Roberts 2005, p. 77.

- Soteriades 1918: Map

- Miller 1966, pp. 543–544.

- Ruches 1965, pp. 162–167.

- Pettifer 2001, p. 7.

Sources

- Anson, Edward M. (2010). "Why Study Ancient Macedonia and What This Companion is About". In Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (eds.). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Oxford, Chichester, & Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 3–20. ISBN 978-1-4051-7936-2.

- Antoniadis, Vyron (2016). Tabula Imperii Romani : J 34 - Athens : Epirus. Athens: Academy of Athens. ISBN 978-960-404-308-8.

- Babiniotis, Georgios (1998). Lexiko tis Neas Ellinikis Glossas. Athens, Greece: Kentro Lexikologias. ISBN 960-86190-0-9.

- Bahr, Lauren S.; Johnston, Bernard; Bloomfield, Louise A. (1997). Collier's Encyclopedia. 11. New York, NY: Collier.

- Blumi, Isa (2002). "The Role of Education in the Albanian Identity and its Myths". In Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (eds.). Albanian Identities: Myth and History. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 49–59. ISBN 0-253-21570-6.

- Borza, Eugene N. (1992). In the Shadow of Olympus: The Emergence of Macedon (Revised ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00880-9.

- Bowden, William (2003). Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Limited. ISBN 0-7156-3116-0.

- Cameron, Alan (2004). Greek Mythography in the Roman World. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517121-7.

- Clogg, Richard (2002) [1992]. A Concise History of Greece (2nd ed.). Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-100479-4.

- Davies, J. K. (2002). "13. A Wholly Non-Aristotelian Universe: The Molossians as Ethnos, State, and Monarchy". In Brock, Roger; Hodkinson, Stephen (eds.). Alternatives to Athens: Varieties of Political Organization and Community in Ancient Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 234–258. ISBN 0-19-925810-4.

- Fleming, Katherine Elizabeth (1999). The Muslim Bonaparte: Diplomacy and Orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00194-4.

- Filos, Panagiotis (2018). "The Dialectal Variety of Epirus". In Giannakis, Georgios; Crespo, Emilio; Filos, Panagiotis (eds.). Studies in Ancient Greek Dialects: From Central Greece to the Black Sea. Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 215–248. ISBN 9783110532135.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Gawrych, George Walter (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman Rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. New York and London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-287-3.

- Georgiev, Vladimir Ivanov (1981). Introduction to the History of the Indo-European Languages. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

- Giakoumis, Kosta (2002). "Fourteenth-century Albanian migration and the 'relative autochthony' of the Albanians in Epeiros. The case of Gjirokastër". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 27: 171–183. doi:10.1179/byz.2003.27.1.171.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1967). Epirus: The Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and the Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1976). Migrations and Invasions in Greece and Adjacent Areas. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes Press. ISBN 0-8155-5047-2.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1982). "ILLYRIS, EPIRUS AND MACEDONIA". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 261–285. ISBN 9780521234474.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1986). A History of Greece to 322 B.C. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-873096-9.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1994). "ILLYRIANS AND NORTH-WEST GREEKS". In Lewis, David M.; Boardman, John; Hornblower, Simon; Ostwald, M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume VI: The Fourth Century B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 422–443. ISBN 9780521233484.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1998). Philip of Macedon. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-2829-1.

- Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (2012) [1949]. The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8.

- Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (1977). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920: A History of East Central Europe. VIII. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96413-8.

- Karabelas, Nikos D. (2015). The Ottoman Conquest of Preveza and its First Castle. XVIth Turkish Congress of History, organised by the Turkish Historical Society, in Ankara, 20-24 September 2010. Volume 4, Part 2, Osmanli Tarihi. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. pp. 967–998. ISBN 978-975-16-2982-1.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Konidaris, Gerasimos (2005). "Examining Policy Responses to Immigration in the Light of Interstate Relations and Foreign Policy Objectives: Greece and Albania". In King, Russell; Mai, Nicola; Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (eds.). The New Albanian Migration. Portland, OR: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 64–92. ISBN 1-903900-78-6.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- McHenry, Robert (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927. New York and London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-1974-3.

- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31617-1.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1984). The Despotate of Epiros, 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-26190-6.

- Osswald, Brendan (2007). "The Ethnic Composition of Medieval Epirus". In Ellis, Steven G.; Klusáková, Lud'a (eds.). Imagining Frontiers, Contesting Identities. Pisa: Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press. pp. 125–154. ISBN 978-88-8492-466-7.

- Pettifer, James (2001). The Greek Minority in Albania – In the Aftermath of Communism. Camberley, Surrey: Conflict Studies Research Centre, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. ISBN 1-903584-35-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 May 2010.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (1998). Nihil Obstat: Religion, Politics, and Social Change in East-Central Europe and Russia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2070-3.

- Reid, James J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839–1878. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 3-515-07687-5.

- Ruches, Pyrrhus J. (1965). Albania's Captives. Chicago, IL: Argonaut Incorporated, Publishers.

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 Years of Greek History and Civilization. Athens, Greece: Ekdotikē Athēnōn. ISBN 960-213-371-6.

- Soteriades, Georgios (1918). An Ethnological Map Illustrating Hellenism in the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor. London: Edward Stanford.

- Soustal, Peter; Koder, Johannes (1981). Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Band 3: Nikopolis und Kephallēnia (in German). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-7001-0399-8.

- Stickney, Edith Pierpont (1926). Southern Albania or Northern Epirus in European International Affairs, 1912–1923. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6171-0.

- Tandy, David W. (2001). Prehistory and History: Ethnicity, Class and Political Economy. Montréal, Québec, Canada: Black Rose Books Limited. ISBN 1-55164-188-7.

- Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War I: Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Incorporated. ISBN 1-85109-420-2.

- Wilkes, John J. (1995). The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Limited. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands, Borderlands: A History of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-3201-9.

External links

- Didrachm of the Epirote League

- Epirus Info Guide

- Panepirotic Federation of America

- Panepirotic Federation of Greece

- Panepirotic Society of Cairo

- Folk music in Epirus by musicologist Christopher C. King