Albert Yava

Albert Yava (1888–1980) was a Hopi–Tewa autobiographer and interpreter. Born in Tewa Village on First Mesa, Arizona, in 1888 to a Hopi father and a Tewa mother, Yava's given name was Nuvayoiyava, meaning Big Falling Snow. He attended primary school in Polacca, Arizona, at a time when compulsory education at US government-run schools was a controversial topic in the Hopi community. Teachers at the school shortened his name to Yava and added the familiar name Albert, both of which names he used for the remainder of his life. Yava subsequently attended boarding school in Keams Canyon, Arizona and spent five years at the Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma.[1][2]

Albert Yava | |

|---|---|

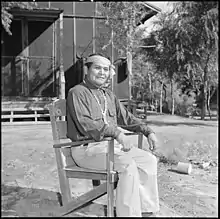

Albert Yava in Poston, Arizona, September 1945 | |

| Native name | Nuvayoiyava |

| Born | 1888 |

| Died | February 1980 (aged 91–92) |

| Occupation | |

| Language | |

| Genre | |

Yava returned to the Hopi reservation in 1912, where he worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs Hopi Agency at Keams Canyon as a painter in the maintenance department. He also served as an interpreter, drawing on his knowledge of Hopi, Tewa, English and some Navajo.[2]

In 1943, Yava provided the Hopi-language text for two bilingual children's books published by the Bureau of Indian Affairs: Field Mouse Goes To War / Tusan Homichi Tuvwöta and Little Hopi / Hopihoya.[2] These works were based on authentic spoken Hopi sources, the first of their kind in Native American education.[3] After World War II, the BIA's emphasis shifted back to assimilation and further efforts at bilingual education would not be made for several decades.[4]

In later life, Yava was regarded as a respected community elder and an authority on both Hopi and Tewa traditions. Considered a member of the Tewa moiety by matrilineal descent, his subsequent induction into the One Horn kiva society made him a member of the Hopi as well.[1]

From 1969–1977, Yava met with anthropologist Harold Courlander to record recollections of his life, Hopi and Tewa history and traditions, and current issues affecting the community such as the Hopi–Navajo land disputes. These recordings were transcribed and edited by Courlander and published in the book Big Falling Snow: A Tewa-Hopi Indian's Life and Times and the History and Traditions of His People in 1978.[1] The work was praised for Yava's insightful narration, balanced treatment of the effects of Western culture on the Hopi, and "ability to reconcile two seemingly polar philosophies: Hopi ceremonialism and Western rationalism".[5] The work invited comparisons with Don C. Talayesva's autobiography, Sun Chief (1963).[1][5]

Yava died in February 1980. An obituary in the International Journal of American Linguistics praised his language skills, calling him a "remarkable man".[2]

References

- Courlander, Harold (1978). Introduction. Big Falling Snow: A Tewa-Hopi Indian's life and times and the history and traditions of his people. By Yava, Albert. Courlander, Harold (ed.). Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. pp. vii–xv. ISBN 0-8263-0624-1. LCCN 82-4797.

- Kennard, Edward A.; Shaul, David L. (1981). "Albert Yava (1888-1980)". Obituary. International Journal of American Linguistics. 47 (4): 340. doi:10.1086/465704. ISSN 0020-7071. S2CID 144595435.

- "Field Mouse Goes To War Tusan Homichi Tuvwöta". Native Child. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- "Little Hopi: Hopihoya". Native Child. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Hepworth, James R. (1979). "Big Falling Snow by Albert Yava". Review. Western American Literature. 14 (2): 181–182. doi:10.1353/wal.1979.0035. ISSN 1948-7142. S2CID 166058747.