Alford plea

An Alford plea (also called a Kennedy plea in West Virginia,[1] an Alford guilty plea[2][3][4] and the Alford doctrine[5][6][7]), in United States law, is a guilty plea in criminal court,[8][9][10] whereby a defendant in a criminal case does not admit to the criminal act and asserts innocence.[11][12][13] In entering an Alford plea, the defendant admits that the evidence presented by the prosecution would be likely to persuade a judge or jury to find the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.[5][14][15][16][17]

Alford pleas are legally permissible in nearly all U.S. federal and state courts, but are not allowed in the state courts of Indiana, Michigan, and New Jersey, or in the courts of the United States Armed Forces.

Origin

The Alford guilty plea is named after the United States Supreme Court case of North Carolina v. Alford (1970).[10][12] Henry Alford had been indicted on a charge of first-degree murder in 1963. Evidence in the case included testimony from witnesses that Alford had said, after the victim's death, that he had killed the individual. Court testimony showed that Alford and the victim had argued at the victim's house. Alford left the house, and afterwards the victim received a fatal gunshot wound when he opened the door responding to a knock.[18]

Alford was faced with the possibility of capital punishment if convicted by a jury trial.[19] The death penalty was the default sentence by North Carolina law at the time, if two requisites in the case were satisfied: the defendant had to have pleaded not guilty, and the jury did not instead recommend a life sentence. Had he pleaded guilty to first-degree murder, Alford would have had the possibility of a life sentence and would have avoided the death penalty, but he did not want to admit guilt. Nonetheless, Alford pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and said he was doing so to avoid a death sentence, were he to be convicted of first-degree murder, after attempting to contest that charge.[18][20] Alford was sentenced to 30 years in prison after the trial judge accepted the plea bargain and ruled that the defendant had been adequately advised by his defense lawyer.[18]

Alford appealed and requested a new trial, arguing he was forced into a guilty plea because he was afraid of receiving a death sentence. The Supreme Court of North Carolina ruled that the defendant had voluntarily entered the guilty plea with knowledge of what that meant. Following this ruling, Alford petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus in the United States District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina, which upheld the initial ruling, and subsequently to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, which ruled that Alford's plea was not voluntary, because it was made under fear of the death penalty.[18] "I just pleaded guilty because they said if I didn't, they would gas me for it," wrote Alford in one of his appeals.[21]

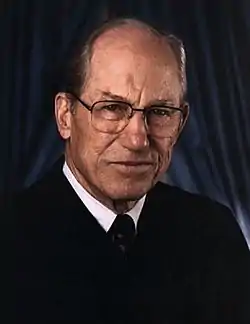

The case was then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Supreme Court Justice Byron White wrote the majority decision,[22] which held that for the plea to be accepted, the defendant must have been advised by a competent lawyer who was able to inform the individual that his best decision in the case would be to enter a guilty plea.[19] The Court ruled that the defendant can enter such a plea "when he concludes that his interests require a guilty plea and the record strongly indicates guilt."[21] The Court allowed the guilty plea with a simultaneous protestation of innocence only because there was enough evidence to show that the prosecution had a strong case for a conviction and the defendant was entering such a plea to avoid this possible sentencing. The Court went on to note that even if the defendant could have shown that he would not have entered a guilty plea "but for" the rationale of receiving a lesser sentence, the plea itself would not have been ruled invalid.[19] As evidence existed that could have supported Alford's conviction, the Supreme Court held that his guilty plea was allowable while the defendant himself still maintained that he was not guilty.[20]

Alford died in prison in 1975.[23]

Definition

The Dictionary of Politics: Selected American and Foreign Political and Legal Terms defines the term "Alford plea" as: "A plea under which a defendant may choose to plead guilty, not because of an admission to the crime, but because the prosecutor has sufficient evidence to place a charge and to obtain conviction in court. The plea is commonly used in local and state courts in the United States."[16] According to University of Richmond Law Review, "When offering an Alford plea, a defendant asserts his innocence but admits that sufficient evidence exists to convict him of the offense."[17] A Guide to Military Criminal Law notes that under the Alford plea, "the defendant concedes that the prosecution has enough evidence to convict, but the defendant still refuses to admit guilt."[15] The book Plea Bargaining's Triumph: A History of Plea Bargaining in America published by Stanford University Press defines the plea as one in "which the defendant adheres to his/her claim of innocence even while allowing that the government has enough evidence to prove his/her guilt beyond a reasonable doubt".[14] According to the book Gender, Crime, and Punishment published by Yale University Press, "Under the Alford doctrine, a defendant does not admit guilt but admits that the state has sufficient evidence to find him or her guilty, should the case go to trial."[5] Webster's New World Law Dictionary defines Alford plea as: "A guilty plea entered as part of a plea bargain by a criminal defendant who denies committing the crime or who does not actually admit his guilt. In federal courts, such plea may be accepted as long as there is evidence that the defendant is actually guilty."[10]

The Alford guilty plea is "a plea of guilty containing a protestation of innocence".[8] The defendant pleads guilty, but does not have to specifically admit to the guilt itself.[24] The defendant maintains a claim of innocence, but agrees to the entry of a conviction in the charged crime.[25] Upon receiving an Alford guilty plea from a defendant, the court may immediately pronounce the defendant guilty and impose sentence as if the defendant had otherwise been convicted of the crime.[13] Sources disagree, as may differing states' laws, as to what category of plea the Alford plea falls under: Some sources state that the Alford guilty plea is a form of nolo contendere, where the defendant in the case states "no contest" to the factual matter of the case as given in the charges outlined by the prosecution.[12] Others hold that an Alford plea is simply one form of a guilty plea,[9][10] and, as with other guilty pleas, the judge must see there is some factual basis for the plea.[13]

Defendants can take advantage of the ability to use the Alford guilty plea, by admitting there is enough evidence to convict them of a higher crime, while at the same time pleading guilty to a lesser charge.[26] Defendants usually enter an Alford guilty plea if they want to avoid a possible worse sentence were they to lose the case against them at trial.[13] It affords defendants the ability to accept a plea bargain, while maintaining innocence.[27]

Court and government use

This form of guilty plea has been frequently used in local and state courts in the United States,[16] though it constitutes a small percentage of all plea bargains in the U.S.[14] This form of plea is not allowed in courts of the United States military.[15][18] In 2000, the United States Department of Justice noted, "In an Alford plea the defendant agrees to plead guilty because he or she realizes that there is little chance to win acquittal because of the strong evidence of guilt. About 17% of State inmates and 5% of Federal inmates submitted either an Alford plea or a no contest plea, regardless of the type of attorney. This difference reflects the relative readiness of State courts, compared to Federal courts, to accept an alternative plea."[28]

In the 1995 case State of Idaho v. Howry before the Idaho Court of Appeals, the Court commented on the impact of the Alford guilty plea on later sentencing.[29] The Court ruled, "Although an Alford plea allows a defendant to plead guilty amid assertions of innocence, it does not require a court to accept those assertions. The sentencing court may, of necessity, consider a broad range of information, including the evidence of the crime, the defendant's criminal history and the demeanor of the defendant, including the presence or absence of remorse."[29] In the 1999 South Carolina Supreme Court case State v. Gaines, the Court held that Alford guilty pleas were to be held valid in the absence of a specific on-the-record ruling that the pleas were voluntary – provided that the sentencing judge acted appropriately in accordance with the rules for acceptance of a plea made voluntarily by the defendant.[30] The Court held that a ruling that the plea was entered into voluntarily is implied by the act of sentencing.[30]

In the 2006 case before the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, Ballard v. Burton, Judge Carl E. Stewart writing for the Court held that an Alford guilty plea is a "variation of an ordinary guilty plea".[32] In October 2008, the United States Department of Justice defined an Alford plea as: "the defendant maintains his or her innocence with respect to the charge to which he or she offers to plead guilty".[31]

In March 2009, the Minnesota House of Representatives characterized the Alford plea as: "a form of a guilty plea in which the defendant asserts innocence but acknowledges on the record that the prosecutor could present enough evidence to prove guilt."[33] The Minnesota Judicial Branch similarly states: "Alford Plea: A plea of guilty that may be accepted by a court even where the defendant does not admit guilt. In an Alford plea, defendant has to admit that he has reviewed the state's evidence, a reasonable jury could find him guilty, and he wants to take advantage of a plea offer that has been made. Court has discretion as to whether to accept this type of plea."[34]

The U.S. Attorneys' Manual states that in the federal system, Alford pleas "should be avoided except in the most unusual circumstances, even if no plea agreement is involved and the plea would cover all pending charges." U.S. Attorneys are required to obtain the approval of an Assistant Attorney General with supervisory responsibility over the subject matter before accepting such a plea.[35][36]

Commentary

In his book American Criminal Justice (1972), Jonathan D. Casper comments on the Supreme Court decision, noting, "The Alford decision recognizes the plea-bargaining system, acknowledging that a man may maintain his innocence but still plead guilty in order to minimize his potential loss."[37] Casper comments on the impact of the Supreme Court's decision to require evidence of guilt in such a plea: "By requiring that there be some evidence of guilt in such a situation, the decision attempts to protect the 'really' innocent from the temptations to which plea-bargaining and defense attorneys may subject them."[37]

US Air Force attorney Steven E. Walburn argues in a 1998 article in The Air Force Law Review that this form of guilty plea should be adopted for usage by the United States military.[18] "In fairness to an accused, if, after consultation with his defense counsel, he knowingly and intelligently determines that his best interest is served by an Alford-type guilty plea, he should be free to choose this path. The system should not force him to lie under oath, nor to go to trial with no promise of the ultimate outcome concerning guilt or punishment. We must trust the accused to make such an important decision for himself. The military provides an accused facing court-martial with a qualified defense attorney. Together, they are in the best position to properly weigh the impact his decision, and the resulting conviction, will have upon himself and his family," writes Walburn.[18] He emphasizes that when allowing these pleas, "trial counsel should establish as strong a factual basis as possible", in order to minimize the possible negative outcomes to "the public's perception of the administration of justice within the military".[18]

—Stephanos Bibas, Cornell Law Review[11]

Stephanos Bibas writes in a 2003 analysis for Cornell Law Review that Judge Frank H. Easterbrook and a majority of scholars "praise these pleas as efficient, constitutional means of resolving cases".[11] Bibas notes that prominent plea bargain critic Albert Alschuler supports the use of this form of plea, writing, "He views them as a lesser evil, a way to empower defendants within a flawed system. As long as we have plea bargaining, he maintains, innocent defendants should be free to use these pleas to enter advantageous plea bargains without lying. And guilty defendants who are in denial should be empowered to use these pleas instead of being forced to stand trial."[11] Bibas instead asserts that this form of plea is "unwise and should be abolished".[11] Bibas argues, "These procedures may be constitutional and efficient, but they undermine key values served by admissions of guilt in open court. They undermine the procedural values of accuracy and public confidence in accuracy and fairness, by convicting innocent defendants and creating the perception that innocent defendants are being pressured into pleading guilty. More basically, they allow guilty defendants to avoid accepting responsibility for their wrongs."[11]

Legal scholar Jim Drennan, an expert on the court system at the Institute of Government at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told the Winston-Salem Journal in a 2007 interview that the ability to use this form of guilty plea as an option in courts had a far-reaching effect throughout the United States.[21] Drennan commented, "We have lots of laws, but human interaction creates unique circumstances and the law has to adapt."[21] He said of the Supreme Court case, "They had to make a decision about what to do. One of the things the court has to do is figure out how to answer new questions, and that is what happened in this case."[21]

Common criticisms of Alford pleas include harm to victims who are denied justice, harm to society from lack of respect for the criminal justice system, the incentive for coercion, violating the right against self-incrimination, hindering rehabilitation by avoiding treatment, and the arbitrary nature in which they are utilized.[38]

See also

References

- Kennedy v. Frazier, 178 W.Va. 10, 357 S.E.2d 43 (1987). ("An accused may voluntarily, knowingly and understandingly consent to the imposition of a prison sentence even though he is unwilling to admit participation in the crime, if he intelligently concludes that his interests require a guilty plea and the record supports the conclusion that a jury could convict him.").

- Shepherd, Jr., Robert E. (November 2000). "Annual Survey of Virginia Law Article: Legal issues involving children". University of Richmond Law Review. University of Richmond Law Review Association. 34: 939.

- Editor, The Montana Lawyer (February 1998). "Regular Features: Discipline Corner: Disbarment follows four years of disciplinary action against Kalispell lawyer". The Montana Lawyer. State Bar of Montana. 23: 23.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Huff, C. Ronald; Martin Killias (2008). Wrongful Conviction. Temple University Press. pp. 143, 289. ISBN 978-1-59213-645-2.

- Daly, Kathleen (1996). Gender, Crime, and Punishment. Yale University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-300-06866-2.

- Thompson, Norma (2006). Unreasonable Doubt. University of Missouri Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-8262-1638-2.

- Neighbors, Ira; Anne Chambers; Ellen Levin; Gila Nordman; Cynthia Tutrone (2002). Social Work and the Law. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7890-1548-8.

- Scheb, John (2008). Criminal Procedure. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-495-50386-6.

- Anderson, James F. (2002). Criminal Justice and Criminology: Concepts and Terms. University Press of America. p. 7. ISBN 0-7618-2224-0.

- Wild, Susan Ellis (2006). Webster's New World Law Dictionary. Webster's New World. p. 21. ISBN 0-7645-4210-9.

- Bibas, Stephanos (2003). "Harmonizing Substantive Criminal Law Values and Criminal Procedure: The Case of Alford and Nolo Contendere Pleas". Cornell Law Review. 88 (6). doi:10.2139/ssrn.348681.

- Champion, Dean J. (1998). Dictionary of American Criminal Justice: Key Terms and Major Supreme Court Cases. Routledge. p. 7. ISBN 1-57958-073-4.

- Gardner, Thomas J.; Terry M. Anderson (2009). Criminal Evidence: Principles and Cases. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-495-59924-1.

- Fisher, George (2003). Plea Bargaining's Triumph: A History of Plea Bargaining in America. Stanford University Press. p. 319. ISBN 0-8047-5135-8.

- Davidson, Michael J. (1999). A Guide to Military Criminal Law. US Naval Institute Press. p. 56. ISBN 1-55750-155-6.

- Raymond, Walter John (1992). Dictionary of Politics: Selected American and Foreign Political and Legal Terms. Brunswick Publishing Corporation. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-55618-008-8.

- Judge, Michael T.; Stephen R. McCullough (November 2009). "Criminal law and procedure". University of Richmond Law Review. University of Richmond Law Review Association. 44: 339.

- Walburn, Steve E. (1998). "Should the Military Adopt an Alford-Type Guilty Plea?". The Air Force Law Review. Judge Advocate General School, United States Air Force. 44: 119–169.

- Solgan, Christopher (Spring 2000). "Life or Death: The Voluntariness of Guilty Pleas by Capital Defendants and the New York Perspective". New York Law School Journal of Human Rights. New York Law School. 16: 699.

- Feinman, Jay M. (2006). Law 101: Everything You Need to Know about the American Legal System. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 327. ISBN 0-19-517957-9.

- Barksdale, Titan (March 28, 2007). "(Not) Guilty – Lawyer in case that led to Alford plea says he worried about later questions". Winston-Salem Journal. p. B1. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- Acker, James R.; David C. Brody (2004). Criminal Procedure: A Contemporary Perspective. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 485–488. ISBN 0-7637-3169-2.

- Turvey, B.E. (2013). Forensic Victimology: Examining Violent Crime Victims in Investigative and Legal Contexts. Elsevier Science. p. 600. ISBN 9780124079205. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- Raum, Michael S.; Jeffrey L. Skaare (2000). "Encouraging Abandonment: The Trend Towards Allowing Parents to Drop Off Unwanted Newborns". North Dakota Law Review. University of North Dakota. 76: 511.

- Mueller, Christopher B.; Laird C. Kirkpatrick (1999). Evidence: Practice Under the Rules. Aspen Publishers. p. 759. ISBN 0-7355-0447-4.

- Duff, Antony (2004). The Trial on Trial, Volume One: Truth and Due Process. Hart Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 1-84113-442-2.

- Marquis, Joshua (Winter 2005). "Symposium: Innocnence in Capital Sentencing: Article: The Myth of Innocence". Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. Northwestern School of Law. 95: 501.

- Harlow, Caroline Wolf (November 2000). "Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases". NCJ 179023. United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original on July 16, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- Cooper, Bob (November 3, 2003). "Coles Enters Guilty Pleas on Two Felony Charges". Office of Attorney General Lawrence Wasden. State of Idaho. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- Nichols, John S.; Felix, Robert L.; Hubbard, F. Patrick; Johnson, Herbert A.; McAninch, William S.; Wedlock, Eldon D. (September–October 1999). "Department: What's New?". South Carolina Lawyer. South Carolina Bar. 11: 48.

- United States Department of Justice (October 2008). "9-16.015 Approval Required for Consent to Alford Plea". Pleas – Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11. www.justice.gov. Archived from the original on November 2, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- Bustos, Fernando (Spring 2007). "Fifth Circuit Survey: June 2005 – May 2006: Survey Article: Civil Rights". Texas Tech Law Review. Texas Tech University School of Law. 39: 719.

- Minnesota House of Representatives (March 27, 2009). "Permanent disqualification". Bill Summary: House Research Department. Minnesota. Archived from the original on December 4, 2009. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- Minnesota Judicial Branch. "Alford Plea". Glossary of Legal Terms. Minnesota. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- "9-27.440 Plea Agreements When Defendant Denies Guilt". February 20, 2015.

- "9-16.015 Approval Required for Consent to Alford Plea". February 20, 2015.

- Jackson, Bruce (1984). Law and Disorder. University of Illinois Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 0-252-01012-4.

- Conklin, Michael (2020). "The Alford Plea Turns Fifty: Why It Deserves Another Fifty Years". Rochester, NY. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Further reading

- McConville, Mike (1998). "Plea Bargainings: Ethics and Politics". Journal of Law and Society. 25 (4): 562–587. doi:10.1111/1467-6478.00103.

- Shipley, Curtis J. (1987). "The Alford Plea: A Necessary But Unpredictable Tool for the Criminal Defendant". Iowa Law Review. 72: 1063. ISSN 0021-0552.

- Ward, Bryan H. (2003). "A Plea Best Not Taken: Why Criminal Defendants Should Avoid the Alford Plea". Missouri Law Review. 68: 913. ISSN 0026-6604.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Look up Alford plea in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Alford Doctrine – State of Connecticut, Judicial Branch

- USAM 9-16.000 Pleas—Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11, United States Department of Justice

- Issue: Effect of Alford Plea of Guilty, Issues In NY Criminal Law, Volume 4, Issue 11.

- Transcript Of Plea Form, North Carolina, with question about term

- Court cases

- North Carolina v. Alford, Supreme Court of the United States

- US v. Szucko, Definition of term by United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

- US v. Bierd, Definition of term by United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit