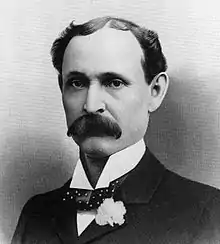

Alfred W. McCune

Alfred William McCune[2] (June 11, 1849 – March 28, 1927) was an American railroad builder, mine operator, and politician from the state of Utah.[3] Owner of several retail and construction businesses, he helped build the Montana Central Railway and a portion of the Utah Southern Railroad, founded the Utah and Pacific Railroad,[4] and built railways in Peru, among other projects. He also owned many profitable mines in Canada, Montana, Peru, and Utah, including the Payne Mine—which paid the most dividends in the history of British Columbia.[4] Late in life, he co-founded the Cerro de Pasco Investment Company, which became the largest copper investor in South America and the largest American investor in Peru until it was nationalized in 1974.[5] He was one of Utah's first millionaires.[6]

Alfred W. McCune | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 11, 1849[1] |

| Died | March 28, 1927 (aged 77)[2] |

| Resting place | Nephi, Utah, U.S. |

| Nationality | British American |

| Occupation | Mine owner, railroad builder, politician |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Ann Claridge |

| Children | Nine children |

| Parent(s) | Matthew and Sarah (Scott) McCune |

He nearly became a U.S. Senator in 1899, but after being unable to receive a majority after numerous ballots and accusations of bribery, the state legislature adjourned without electing anyone to the seat.[7] The Senate seat remained vacant for two years, and in 1901 another man was elected to the position.[7]

As of the early 21st century, his Salt Lake City mansion, the Alfred McCune Home, was still considered one of the grandest homes ever built in the American West.[8] It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[9]

Early life

McCune was born at Fort William in Calcutta, India, on June 11, 1849, to Matthew and Sarah (Scott) McCune.[1] His father was born in 1811 on the Isle of Man, the son of Robert McCune and Agnes Jelly.[10] Raised from infancy in Scotland, Matthew McCune traveled to London in 1835, joined the British Army, and married Sarah Elizabeth Caroline Scott.[10] (He rose to the rank of captain in the artillery.)[10] Alfred's mother, Sarah, had been born in London, where her family had resided for generations.[1] Matthew McCune was assigned to Ft. William and the couple moved there the same year they were married.[10] The McCunes had seven sons and one daughter, Alfred William McCune being the second-to-last to be born.[1] All the children were born at Fort William, and three of the boys and the daughter all died there.[1] The McCunes were members of the Plymouth Brethren Christian church.[10] In 1851, after a church meeting in the McCune home, two sailors who were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the "LDS Church," or Mormonism) converted the McCunes to Mormonism.[10]

In 1854, Matthew McCune was sent to Rangoon, Burma, where he became a Mormon missionary in his spare time.[1][10] Young Alfred was educated at home by Mormon missionaries for the next two years.[1] Matthew McCune resigned from the British Army in late 1856,[1] and on either December 6[1] or December 10[10] (sources differ) they set sail from Calcutta for New York City, arriving on March 3, 1857.[10] Alfred had never seen snow before; he thought it was salt falling from the sky.[11] After three months in New York City, the family traveled by rail to Chicago, where they proceeded by wagon to Salt Lake City,[12] arriving on September 21, 1857.[12][10] The family stayed with one family and then another in Farmington, Utah, for a few months before moving to Nephi, Utah in 1858.[12][10]

Matthew McCune married Ann Midgley in 1859, and Isabella Chalmers in 1865.[10] His second and third wives bore him another 15 children.[10] Sarah McCune died in 1877.[12] Matthew McCune died in Nephi in October 1889.[10]

Business career

In his middle and late teens, Alfred McCune worked as a farmer and stock herder.[12] When he was 19, he worked as a laborer on the Union Pacific Railroad (then pushing through Echo Canyon in Summit County, Utah), and then ranched cattle for a time with his brother Edward.[12]

In 1871, the Utah Southern Railroad began construction across the lower portion of the state of Utah. With business partner Joel Grover, he began supplying the railroad workers with hay, grain, and provisions.[13][14] In 1878, McCune added a third business partner, Walter P. Read, and they built the Utah Southern Railroad Extension from Milford to Frisco in 1880–1881.[12][14][15] The three opened a general store in Milford, which proved highly profitable.[12] In 1881, McCune joined Thomas Scofield in opening a 6,000-acre (2,400 ha) cattle and horse ranch in southern Utah.[14]

McCune married Elizabeth Ann Claridge at Endowment House in Salt Lake City on July 1, 1872.[12][13] Elizabeth, born February 19, 1852, in Hemel Hempstead, England, was the daughter of Samuel Claridge, a convert to the Latter-day Saints movement who had emigrated to the United States in 1853 and became prominent local leader in the church.[16] The couple made their home in Nephi,[13] had nine children (Alfred Jr., Harry, Earl, Raymond, Sarah Fay, Frank, Jacketta, Marcus, and Elizabeth).[17]

McCune participated in a number of railroad, mining, and other business ventures in the late 19th century. Beginning in 1879, McCune's joint business venture—Grover, McCune & Read—helped grade portions of the Rio Grande Railroad, Denver and South Park Railroad, Denver and New Orleans Railroad, and Oregon Short Line Railroad.[12][18] It also supplied wood fuel to Lexington Mines in the state of Montana.[12][18] But in the winter of 1882, Grover and Read, concerned about economic conditions and worried the firm was over-extended, pulled out of the business.[12] McCune formed his own company, which bought out a general store near Butte, Montana, and supplied wood fuel to mines in that city.[12] In 1883, he formed a joint partnership with John W. Caplis (also known as John Caplice) to provide capital for his fuel and retail businesses, but within a year Caplis withdrew from the company.[12] In 1885, his old business partners John Caplis and Walter Read joined McCune and Helena, Montana, businessman Hugh Kirkendall in forming a construction company to build 200 miles (320 km) of the Montana Central Railway from Butte to Great Falls, Montana.[19] The new firm also extended the Union Pacific Railroad's Oregon Short Line to Anaconda, Montana and Butte.[19] Shortly thereafter, mine owner Marcus Daly solicited contracts from firms to provide wood fuel for his mines in Butte as well as wood to help build the town. Daly asked for the huge amount of 300,000 cords.[20] McCune formed a new company with Caplis and another man (John Branagan) to supply the wood.[18][20] Eighty teams of horses and mules worked alongside 650 men to haul logs out of the forest, and the company built a massive wooden flume to float the logs out of Mill Creek Canyon (where they could be picked up and hauled by wagon into Butte).[20] When McCune was done extending the Oregon Short Line to Anaconda, he extended his flume another 25 miles (40 km) to allow logs to make to that booming mining town.[20] Because of these business interests, the McCunes relocated to Montana in 1885.[21] Three years later, with McCune having fulfilled most of his wood supply contracts, the couple moved to Salt Lake City.[19][21] They purchased a home at 2nd West and South Temple streets,[19] near the Union Pacific railroad depot.[22]

McCune's business interests turned to mining in the 1890s. Beginning around 1891, McCune purchased interests in a number of highly productive and famous mines in British Columbia, including the Freddie Lee, Krao, Libbie, Maid of Erin, Mountain Chief, Nickel Plate, Skyline, Payne, Two Jacks, and War Eagle.[18][23]

McCune's interest in railroads and other businesses had not abated, however. In April 1889,[19] he purchased a one-third interest in Salt Lake City's streetcar system,[24] and converted it from mule-drawn wagons to electric.[22] He also formed a company which in May 1891 took over the Salt Lake Herald (at the time, the Salt Lake Tribune's biggest competitor).[25] In 1895, he co-founded and became part-owner of the Utah Power Company.[26] In February 1897, the McCunes undertook a lengthy tour of the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and the Far East.[27] They rented a large home in the English seaside town of Eastbourne.[22] They returned to Utah in March 1898.[28] In August 1898, McCune and other investors formed the Utah and Pacific Railroad (U&P), with the purpose of building 75 miles (121 km) of track from Milford to Uvada, Utah.[4] The Oregon Short Line supplied the rails and ties for the U&P, and on February 2, 1899, the Oregon Short Line announced it would build a railroad that would connect the U&P at Uvada with the California state line.[29]

McCune's business interests in the last three decades of his life focused on Peru. In 1887, he formed a mining syndicate with mine investor James Ben Ali Haggin to investigate mine properties in the Pasco Region of Peru.[30] McCune visited Peru for several months in the spring of 1901 to assess these properties.[17] In 1902, the two men set up the Cerro de Pasco Investment Company and added new shareholders, which included businessman Henry Clay Frick, Michael P. Grace, Phoebe Hearst, Darius Ogden Mills, J. P. Morgan, and Hamilton McKown Twombly (an heir to the Vanderbilt fortune).[5][30] The same year, the government of Peru awarded McCune a contract to survey a railroad route from Huacho to Cerro de Pasco.[31] McCune and his family traveled in Peru in 1902 to visit his various business ventures there.[32] Six years later, the government gave him a contract to build both the Cerro de Pasco Railroad which he had previously survey as well as the Ucayali Railroad along the Ucayali River in the Ancón District.[33] In 1912, McCune incorporated the Amazon and Pacific Railway Company, with the intent of building 190 miles (310 km) of railroad from Cerro de Pasco to the Pacific Ocean.[34] The Peruvian government gave McCune 5,000,000 acres (2,000,000 ha) of land if he completed the route, and operated it for 25 years.[34] Cerro de Pasco Investment subsequently purchased a controlling interest most of the mines in the Pasco Region as well as the Cerro de Pasco Railroad.[30][35] It soon owned the Oroya Railroad, a very large copper mine in the Morococha District, and the giant productive Casapalca mine.[35][36] By 1916, the company had more than $30 million invested in copper mining in Peru.[35] This was the largest copper investment anywhere in South America, and probably the largest in the world outside the United States.[35] Cerro de Pasco Investment Company remained the largest American investor in Peru throughout the 20th century, until it was nationalized in 1974.[37] (In 1957, the "McCune Pit"—named for Alfred W. McCune—opened in Cerro de Pasco. Roughly 80 percent of all copper mined in the Pasco Region came from the McCune Pit in 1960.)[38]

Political career

McCune was actively involved in politics in Utah in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[8] The McCunes were Salt Lake City's most prominent citizens, and their home was a salon for politics and culture.[8] In mid-August 1898, McCune decided to seek office as a Democrat for the United States Senate.[39] State legislators had already indicated they would not support the incumbent, Frank J. Cannon for reelection. Cannon, a Republican, had voted against the Dingley Act, which would have raised tariffs on sugar and helped the Utah sugar industry.[40] The Dingley bill was strongly supported by the LDS Church hierarchy, who now opposed his reelection.[40] Other factors were his support for Free Silver; rumors about immoral acts he may have committed while living in Washington, D.C.; and that the Utah legislature was controlled by Democrats.[40] The McCunes were close friends with Heber J. Grant, seventh LDS Church president and an ordained LDS apostle.[8] Although the LDS church had (just weeks before) made a decision to stay out of state politics, McCune asked Grant for the church's assistance in winning office.[39] Grant consulted with Joseph F. Smith (Apostle and sixth LDS president) and John Henry Smith (a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and the First Presidency of the LDS Church), both of whom supported McCune's senatorial bid.[39] But McCune was not alone in seeking the office. Former Representative William H. King was also running (and backed by two Apostles), as was James Moyle (a prominent attorney and founder of the Utah Democratic Party who was backed by state legislators) and George Q. Cannon (an Apostle and member of the First Presidency).[39]

At the time, members of the Senate were still elected by their respective state legislatures.[39] The Utah state legislature convened in January 1899.[7] There were 13 Republicans and 50 Democrats in the state legislature.[41] From the beginning, McCune was considered the leading candidate.[7] But the legislature quickly deadlocked over the election. One-hundred and twenty-one ballots were cast, and no winner emerged.[7] McCune was one or two votes shy of winning on several ballots.[7] on February 18, before the 122nd ballot, state representative Albert A. Law (a Republican from Cache County and a Cannon supporter) claimed McCune offered him $1,500 for his vote.[42] McCune strenuously denied the charge, and a seven-member legislative committee was established to investigate the allegation.[7][42] The committee voted 7-to-2 to absolve McCune of the charge, and this outcome was announced to the legislature on March 6.[7][42] Balloting resumed, and on March 8, on the 149th ballot, McCune still lacked enough votes to win office (he had only 25 votes).[7][42] The legislature adjourned without having chosen a senator,[43] and McCune traveled in Europe for several weeks to regain his health (returning in June 1899).[17]

Utah's U.S. Senate seat remained vacant until January 1901. The Republicans regained their majority in the state legislature in the election of 1900, and elected Thomas Kearns to fill the seat.[7] The election was still hotly disputed. Kearns received only 8 votes on the first ballot, and balloting continued for four more days.[44] On January 22, Kearns won the election by a vote of 37-to-25 (with a unanimous block of Democrats voting for McCune).[44][45]

McCune ran for governor of Utah in 1916. His Democratic primary opponent was 70-year-old millionaire Simon Bamberger, state senator, and a Jew.[46] Neither man won a majority of the vote on the first ballot at the Democratic State Convention.[47] B. H. Roberts, then LDS Church historian and member of the First Council of the Seventy, delivered what historians have characterized as a "brilliant" speech declaring that voters should not select candidates on the basis of their religion.[48] Bamberger was elected on the second ballot, and went on to easily defeat his opponent in the general election.[48]

Religious beliefs, home, and death

The status of McCune's religious beliefs is open to dispute. Mormon missionary Stuart Martin wrote in 1920 that McCune was not a Mormon, but had many Mormon friends and had given much money to the church.[49] Judge Orlando Powers, Associate Justice of the Utah Supreme Court, said in 1906 that he understood that McCune was not a Mormon.[41] Frank J. Cannon, too, claimed McCune was not a Mormon,[50] and B. H. Roberts, LDS Church historian and member of the First Council of the Seventy, said in 1930 that McCune was not a church member.[51] Historian Orvin Malmquist, however, says that church records show he was baptized into the LDS Church at the age of eight in 1857, and that his marriage to Elizabeth Claridge in a Mormon temple in 1872 could not have occurred without his being a church member.[52] It is not in dispute that he was baptized by proxy in 1969.[52]

In June 1897, Alfred McCune rented Gardo House from the LDS Church.[53][54] At this time, the couple decided to build their own home. Alfred gave his wife, Elizabeth, carte blanche in designing and furnishing the home.[22] The McCunes hired Salt Lake City architect S. C. Dallas to build their home, and then sent him to Europe for two years to study architectural styles.[55] The home Dallas designed was built in a combination of the Shingle and the Stick architectural styles.[9][56][57] The McCunes vacated Gardo House (probably in 1900), and moved into the home of McCune's business partner and friend, Thomas R. Ellerbeck (at 140 B Street).[17] A few months after Alfred's return from Peru in June 1901,[17] the McCune family moved into their new mansion.[22][55][56] The cost of the home was unclear; the McCunes stopped counting the costs after they reached $500,000.[58] It was for many years considered the costliest home in Salt Lake City.[59] The home has been described as a showpiece and one of the grandest homes in the Western United States.[8][60] (It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.)[9]

Final years and death

Alfred McCune continued to be heavily involved in business in his 50s and 60s. But according to McCune's long-time friend Heber Grant, by 1908 McCune's desire to earn money had overwhelmed his Mormon faith.[61] Grant believed McCune's children had lost their faith as well due to their father's avarice.[61] McCune's extensive business interests also took him away from his wife for long periods of time.[62]

In 1920, the McCunes moved to Los Angeles, California. Alfred was 71 years old, and the move was apparently prompted by California's mild climate.[24] On October 7, 1920,[62] the McCunes donated their Salt Lake City mansion to the LDS Church.[59] The couple stayed at the Hotel Van Nuys for an extended period upon their arrival in Los Angeles.[63] In January 1921, they purchased the home of W.W. Mines at 626 South Kingsley Drive for $30,000.[62][64] When the Los Angeles Stake was formed in January 1923, McCune's nephew, George W. McCune, was selected as president of the Stake.[65]

Elizabeth McCune's health began to deteriorate over the next several years. In 1923, the couple sold their California home, returned to Salt Lake City, and began construction of a new home in the northeast part of the city.[63] With this home still unfinished, the couple took a long vacation in Bermuda in the spring of 1924.[63] But Elizabeth fell ill during the trip, and they returned to Salt Lake City and took up residence in the Hotel Utah.[63] Her health worsened, and McCune's extensive family rushed to Salt Lake to be at her side.[63] She died on August 1, 1924.[2][59] A public funeral was held for her at Temple Square and she was buried in Nephi.[2]

In November 1926, McCune traveled to Europe with some family members.[66] He never returned to the United States. McCune died on March 28, 1927, in Cannes, France.[2] He was buried next to his wife in Nephi.[2][53]

References

- Whitney, 1904, p. 505.

- Van Wagoner, p. 100.

- Whitney, 1904, p. 505–508.

- Myrick, p. 625-626.

- Clayton, p. 86-87.

- Ellsworth, p. 30. Accessed 2011-04-18.

- Whitney, 1916, p. 527.

- Wadley, Carma. "A Unique 100-Year-Old Heirloom.' Deseret News. April 19, 2001.

- "Alfred W. McCune Mansion." Inventory - Nomination Form. National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. June 13, 1974. Accessed 2011-04-18.

- Jensen, p. 161.

- Whitney, 1904, p. 505-506.

- Whitney, 1904, p. 506.

- Van Wagoner, p. 93.

- Jensen, p. 495.

- Massey and Wilson, p. 211.

- Van Wagoner, p. 90.

- Whitney, 1904, p. 508.

- Van Wagoner, p. 94.

- Whitney, 1904, p. 507.

- Morris, p. 31.

- Gates, p. 330.

- Van Wagoner, p. 95.

- Minister of Mines' Office, p. 664, 698, 700; Morrison and De Soto, p. 696; Roche, p. 122; Norman, p. 254.

- Goodman, p. 53.

- Malmquist, p. 173; "The New Salt Lake 'Herald'." The Deseret Weekly. June 6, 1891.

- "Electric Light and Power," p. 148.

- Whitney, 1904, p. 609.

- Whitney, 1904, p. 610.

- Myrick, p. 626.

- Waszkis, p. 87.

- "Concession for Americans." New York Times. February 9, 1902.

- Van Wagoner, p. 97.

- "Alfred McCune to Build Two Railroads for the Peruvians." New York Times. January 6, 1908; Quiroz, p. 216.

- Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, p. 519.

- Clayton, p. 87.

- Levesque, p. 90.

- Clayton, p. 86.

- Dore, p. 144.

- Alexander, p. 10.

- Powell, p. 70.

- Committee on Privileges and Elections, p. 860.

- Committee on Privileges and Elections, p. 863.

- "Utah With One Senator." New York Times. March 11, 1899.

- Appleton's Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events, p. 771.

- Powell, p. 158.

- Maisel, p. 306.

- Murphy, Miriam B. "Simon Bamberger." Utah History Encyclopedia. 2010. Accessed 2011-04-22.

- Powell, p. 26.

- Martin, p. 213.

- Cannon, p. 221.

- Roberts, p. 344.

- Malmquist, p. 443.

- Brimhall, Sandra Dawn. "The Gardo House: A History of the Mansion and Its Occupants." Utah History to Go. 2010. Accessed 2011-04-22.

- Another source says that the McCunes did not rent Gardo House until their return from Europe in March 1898. See: Van Wagoner, p. 95.

- Wilkerson, p. 8, 10.

- Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, p. 345.

- Goodman, p. 52.

- Van Wagoner, p. 96.

- Nibley, p. 99.

- Smith and Trimble, p. 71.

- Alexander, p. 184.

- Van Wagoner, p. 98.

- Van Wagoner, p. 99.

- "Sharp Cut in House Prices Announced." Los Angeles Times. January 30, 1921.

- "Stake of 'Zion' Formed." Los Angeles Times. January 22, 1923.

- "Alfred McCune of Utah Dies in France." Los Angeles Times. March 30, 1927.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Thomas G. Mormonism in Transition. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1996.

- Appleton's Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1902.

- Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce. Commerce Reports. Vol. 2. Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce. Bureau of Manufactures. U.S. Department of Commerce. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1912.

- Cannon, Frank J. Under the Prophet in Utah: The National Menace of a Political Priestcraft. Boston: C.M. Clark Publishing Co., 1911.

- Clayton, Lawrence. Peru and the United States: The Condor and the Eagle. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1999.

- Committee on Privileges and Elections. In the Matter of the Protests Against the Right of Hon. Reed Smoot, A Senator From the State of Utah, to Hold His Seat. Doc. No. 486. 59th Cong, 1st Sess. Committee on Privileges and Elections. United States Senate. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1906.

- Dore, Elizabeth. The Peruvian Mining Industry: Growth, Stagnation, and Crisis. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1988.

- "Electric Light and Power." Engineering News. May 9, 1895.

- Ellsworth, S. George. "Heeding the Prophet's Call." Ensign. October 1995.

- Gates, Susan Young. "Biographical Sketches: Mrs. Elizabeth Claridge McCune." The Young Women's Journal of the Y.L.M.J. Associations. August 1989.

- Goodman, Jack. As You Pass By: Architectural Musings on Salt Lake City. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1995.

- Jensen, Andrew. Latter-Day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia. Salt Lake City: A. Jenson History Co., 1920.

- Levesque, Rodrique. Railways of Peru. Gatineau, Quebec: Levesque Publications, 2008.

- Maisel, Louis S. Jews in American Politics. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.

- Malmquist, Orvin Nebeker. The First 100 Years: A History of the 'Salt Lake Tribune', 1871-1971. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1971.

- Martin, Stuart. The Mystery of Mormonism. London: Odhams, 1920.

- Massey, Peter and Wilson, Jeanne. Utah Trails: Northern Region. Hermosa Beach, Calif.: Adler Publishing, 2006.

- Minister of Mines' Office. Annual Report of the Minister of Mines for the Year Ending 1891. British Columbia. Minister of Mines' Office. Vancouver, B.C.: Minister of Mines, 1891.

- Morris, Patrick F. Anaconda, Montana: Copper Smelting Boom Town on the Western Frontier. Bethesda, Md.: Swann Publishing, 1997.

- Morrison, R.S. and De Soto, Emilio D. The Mining Reports. Chicago: Callaghan & Co., 1905.

- Myrick, David F. The Southern Roads. Reno, Nev.: University of Nevada Press, 1992.

- Nibley, Preston. Stalwarts of Mormonism. Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1954.

- Norman, Sidney. Northwest Mines Handbook: A Reference Book of the Mining Industry of Idaho, Washington, British Columbia, Western Montana, and Oregon. Spokane, Wash.: Northwest Mining Association, 1918.

- Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation. The Preservation of Historic Architecture: The U.S. Government's Official Guidelines for Preserving Historic Homes. Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation. Technical Preservation Services Division. U.S. Department of the Interior. Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 2004.

- Powell, Allan Kent. Utah History Encyclopedia. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1995.

- Quiroz, Alfonso W. Corrupt Circles: A History of Unbound Graft in Peru. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2008.

- Roberts, Brigham Henry. A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints: Century I. Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1930.

- Roche, Gus. "Ainsworth—Its Mines and History." Mining: The Journal of the Northwest Mining Association. March 1896.

- Smith, Scott T. and Trimble, Stephen. Salt Lake Impressions. Helena, Mont.: Farcountry Press, 2007.

- Van Wagoner, Carol Ann S. "Elizabeth Ann Claridge McCune: At Home on the Hill." In Worth Their Salt: Notable But Often Unnoted Women of Utah. Colleen Whitley, ed. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1996.

- Waszkis, Helmut. Mining in the Americas: Stories and History. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead, 1993.

- Whitney, Orson Ferguson. History of Utah. Salt Lake City: G.Q. Cannon, 1904.

- Whitney, Orson Ferguson. Popular History of Utah. Salt Lake City: The Deseret News, 1916.

- Wilkerson, Christine. Building Stones of Downtown Salt Lake City: A Walking Tour. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey, 1999.