Alison and Peter Smithson

Alison Margaret Smithson (22 June 1928 – 14 August 1993) and Peter Denham Smithson (18 September 1923 – 3 March 2003) were English architects who together formed an architectural partnership, and are often associated with the New Brutalism (especially in architectural and urban theory).[1][2]

Alison Margaret Smithson (née Gill) Peter Denham Smithson | |

|---|---|

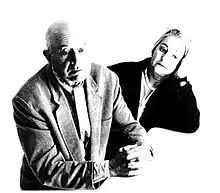

Peter and Alison Smithson in 1990 | |

| Born | June 22, 1928 September 18, 1923 Sheffield, Yorkshire, England Stockton-on-Tees, England |

| Died | August 16, 1993 (aged 65) March 3, 2003 (aged 79) London, England London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Architect |

Personal lives

Peter was born in Stockton-on-Tees in County Durham, north-east England, and Alison Margaret Gill[3] was born in Sheffield, West Riding of Yorkshire. Peter served in the Madras Sappers and Miners in India and Burma,[4] then returned to finish his architectural studies. They met while studying architecture at Durham University and married in 1949. They joined the architecture department of the London County Council as Temporary Technical Assistants before establishing their own partnership in 1950.[5]

Of their three children, Simon, Samantha and Soraya,[4] one, Simon, is likewise an architect.[6]

Alison Smithson was also a novelist; her A Portrait of the Female Mind as a Young Girl was published in 1966.

Studies

Alison Smithson studied architecture at King's College (now Newcastle University), University of Durham between 1944 and 1949. Peter Smithson studied architecture at the same university between 1939 and 1948, along with a programme in the Department of Town Planning, also at King's, between 1946 and 1948.[7]

Work

The Smithsons first came to prominence with Hunstanton School, completed in 1954, which used some of the language of high modernist Ludwig Mies van der Rohe but in a stripped back way, with rough finishes and a deliberate lack of refinement that kept architectural structure and services exposed.[8] They are arguably among the leaders of the British school of New Brutalism. They referred to New Brutalism as "an ethic, not an aesthetic".[9] Indeed, their work sought to emphasize functionality and connect architecture with what they viewed as the realities of modern life in post-war Britain.[10] Alison Smithson articulated their desire to connect building, users, and site when, describing architecture as an act of "form-giving", she noted: "My act of form-giving has to invite the occupiers to add their intangible quality of use."[11] After the critical success of Hunstanton School, they were associated with Team X and its 1953 revolt against old Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) philosophies of high modernism.

Among their early contributions were 'streets in the sky' in which traffic and pedestrian circulation were rigorously separated, a theme popular in the 1960s. They were members of the Independent Group participating in the 1953 Parallel of Life and Art exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts and This Is Tomorrow in 1956. Throughout their career they published their work energetically, including their several unbuilt schemes, giving them a profile, at least among other architects, out of proportion to their relatively modest output.

Peter Smithson's teaching activity included the participation for many years at the ILAUD workshops together with fellow architect Giancarlo De Carlo.

National Life Stories conducted an oral history interview (C467/24) with Peter Smithson in 1997 for its Architects Lives' collection held by the British Library.[12]

Built projects

Their built projects include:

- Smithdon High School, Hunstanton, Norfolk (1949–54; a Grade II* listed building)[13]

- The House of the Future exhibition (at the 1956 Ideal Home Show)

- Sugden House, Watford (1956)

- Upper Lawn Pavillion, Fonthill Estate, Tisbury, Wiltshire (1959–62)

- The Economist Building, Piccadilly, London (1959–65)

- Garden building, St Hilda's College, Oxford (1968)[14]

- Private house extension for Lord Kennet, Bayswater, London, 1960

- Robin Hood Gardens housing complex, Poplar, East London (1969–72)[15]

- Buildings at the University of Bath, including the School of Architecture and Building Engineering (1988)

- Their last project: the Cantilever-Chair Museum of the Bauhaus design company TECTA in Lauenfoerde, Germany

Robin Hood Gardens was under construction when B. S. Johnson made a short film about the couple for the BBC, The Smithsons on Housing (1970). Sukhdev Sandhu, in a blog entry for the London Telegraph website, wrote that "they drone in self-pitying fashion about vandals and local naysayers to such an extent that any traces of visionary utopianism are extinguished."[16] The finished flats suffered from high costs associated with the system selected and from high levels of crime, all of which undermined the modernist vision of 'streets in the sky' and the Smithsons' architectural reputation.[17] In 2017, with the flats set to be demolished, a three-storey section including a walkway and maisonette interiors was acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum.[15]

They would go on to design several buildings at Bath, while relying mainly on private overseas commissions and Peter Smithson's writing and teaching (he was a visiting professor at Bath from 1978 to 1990, and also a unit master at the Architectural Association School of Architecture).

Unbuilt proposals

Their unbuilt schemes include:

- Coventry Cathedral unsuccessful competition entry, 1951

- Golden Lane Estate unsuccessful competition entry, 1952

- Sheffield University, unsuccessful competition entry

- Hauptstadt, unsuccessful competition entry, 1957

- British Embassy, Brasília, competition-winning design, unbuilt due to financial constraints, 1961

Bibliography

- Crinson, Mark, Alison and Peter Smithson, Historic England, 2018

- Boyer, Christine M., Not Quite Architecture. Writing around Alison and Peter Smithson, Cambridge MA, The MIT Press, 2018

- Henley, Simon (2017) Brutalism Redefined, RIBA Publications; ISBN 978-185-946-5776

- Powers, Alan (September 2008) 'Casework' The Twentieth Century Society: Robin Hood Gardens

- Risselada, Max; van den Heuvel, Dirk (2005) Team 10: In Search of a Utopia of the Present, NAi Publishers,Rotterdam, 320 pages. ISBN 90-5662-471-7

- Van den Heuvel, Dirk, Risselada, Max (eds.), Alison and Peter Smithson. From the House of the Future to a House of Today, 010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2004 ISBN 90-6450-528-4

- A.R.Emili, Pure and simple, the Architecture of New Brutalism, Ed. Kappa, Rome 2008[18]

- Webster, Helena (ed.), Modernism without Rhetoric. Essays on the Work of Alison and Peter Smithson, Academy Editions, London, 1997

- Vidotto, Marco, A+P Smithson. Pensieri, progetti e frammenti fino al 1990, Genova, Sagep Editrice, 1991

- Books

- Smithson, Alison. A Portrait of the Female Mind As a Young Girl: A Novel. Chatto & Windus, 1966.

- Smithson, Alison, and Peter Smithson. Urban Structuring : Studies. Reinhold U.a, 1967.

- Smithson, Alison, and Peter Smithson. Ordinariness and Light: Urban Theories, 1952-1960. MIT Press, 1970.

- Smithson, Alison, and Peter Smithson. Without Rhetoric: An Architectural Aesthetic, 1955-1972. M.I.T. Press, 1974.

- Smithson, Alison, and Peter Smithson. The Heroic Period of Modern Architecture. Rizzoli, 1981.

- Articles

- Smithson, Alison, and Peter Smithson. “Density, Interval and Measure.” Ekistics, vol. 25, no. 147, 1968, pp. 70–72.

- Smithson, Alison, and Peter Smithson. “The New Brutalism.” October, vol. 1, no. 136, 2011, pp. 37–37.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alison and Peter Smithson. |

- Alison and Peter Smithson, Design Museum Archived 2010-11-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Peter & Alison Smithson - Open University

- Banham, Mary (18 August 1993). "Obituary: Alison Smithson". The Independent. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Rowntree, Diana (8 March 2003). "Simon, Samantha and Soraya". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Morgan, Ann Lee (1987). Contemporary Architects, Second Edition. Chicago and London: St. James Press. pp. 851. ISBN 0-912289-26-0.

- http://www.bdonline.co.uk/interview-simon-smithson/3107017.article

- Smithson, Peter and Alison. 2001. pg.19–20

- Davies, Colin (2017). A New History of Modern Architecture. London: Laurence King Publishing. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-78627-056-6.

- Davies, Colin (2017). A New History of Modern Architecture. London: Laurence King Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-78627-056-6.

- Goodwin, Dario (22 June 2017). "Spotlight: Alison and Peter Smithson". www.archdaily.com.

- Morgan, Ann Lee (1987). Contemporary Architects. Chicago and London: St. James Press. pp. 853. ISBN 0-912289-26-0.

- National Life Stories, 'Smithson, Peter (1 of 19) National Life Stories Collection: Architects' Lives', The British Library Board, 1997. Retrieved 10 April 2018

- Historic England. "SMITHDON SCHOOL INCLUDING MAIN BLOCK WATER TOWER WORKSHOPS AND KITCHENS, Hunstanton (1077909)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- "The Buildings". St Hilda's College, Oxford. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- Brown, Mark (9 November 2017). "V&A acquires segment of Robin Hood Gardens council estate". Guardian. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Sandhu, Sukhdev (16 June 2009). "B.S. Johnson, Brutalist". 3:AM Magazine. cross-posted from telegraph.co.uk blogs. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Alison and Peter Smithson, Design Museum. Archived 2010-11-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Emili, Anna Rita (2008). Pure and simple, the architecture of New Brutalism (Kappa ed.). Rome: Kappa. p. 252. ISBN 9788878908888.

Sources

- Smithson, Alison and Peter (2001). The Charged Void: Architecture. New York City: Monacelli Press, Inc. ISBN 1-58093-050-6.