Allonemobius fasciatus

Allonemobius fasciatus, commonly known as the striped ground cricket, is an omnivorous species of cricket that belongs to the subfamily Nemobiinae.[1] A. fasciatus is studied in depth in evolutionary biology because of the species ability to hybridize with another Allonemobius species, A. socius.[2]

| Allonemobius fasciatus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Orthoptera |

| Suborder: | Ensifera |

| Family: | Trigonidiidae |

| Genus: | Allonemobius |

| Species: | A. fasciatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Allonemobius fasciatus (De Geer, 1773) | |

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Subspecies

These two subspecies belong to the species Allonemobius fasciatus:

- Allonemobius fasciatus abortivus (Caudell, 1904)

- Allonemobius fasciatus fasciatus (De Geer, 1773)

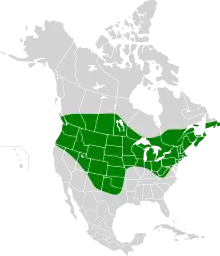

Distribution

A. fasciatus is widely distributed in North America,[4] covering eastern and western portions.[5] A. fasciatus typically prefers short grassland habitats.[6] Depending where A. fasciatus resides, traits such a body size can differ.[4] Within North America, there are various hybrid zones, such as in New Jersey, where A. fasciatus has the ability to hybridize with a close relative, A. socius.[7]

A. fasciatus is considered to inhabit northern regions of North America, whereas A. socius inhabits southern regions.[6] In areas where topography can vary, like in mountain regions, A. fasciatus is believed to be found at higher elevations, whereas A. socius is believed to be found in lower elevations.[8] This can be referred to as a mosaic hybrid zone.[8] A mosaic hybrid zone occurs because the habitat ranges for A. fasciatus and A. socius overlap.[9] While it is known that for the most part A. fasciatus remains separated from A. socius when breeding, the potential for interbreeding can occur.[6]

Behaviour

Communication

Mating calls appear to be related to genotype.[7] Male mating calls amongst A. fasciatus function in interspecific and intraspecific species recognition.[7] Adult male mating calls are influenced in the nymph stage by temperature and length of daylight. [7] Usually, males will avoid moving areas when calling female conspecifics.[6] With the ability for breeding hybridization with A. socius, members of the A. fasciatus species present song calls that are undifferentiated to A. socius by female A. fasciatus.[7][6] Females have the ability to leave a pheromonal residue on surfaces.[6]

Mate Selection

Females are highly sex-driven and will chose a male to mate with based on the mating call she prefers.[6] When female A. fasciatus hybridizes with A. socius males, she loses very little except the energy expended when looking for the male, and risk associated with potential predation.[6]

Physiology

A. fasciatus wing size is determined by the number of hours of daylight present during development.[5] Most individuals are short-winged[5] and longer daylight periods can account for larger wing size.[5]

Life Cycle

A. fasciatus is a univoltine species.[1][10]

It can take a nymph up to two months to hatch.[5]

This species is photosensitive and development will increase in speed as daylight decreases.[5] This phenomenon is indicative of seasonal synchrony.[5]

Reproduction

Hybridization

Ground-dwelling crickets only possess XX and XO chromosomes, which allows male individuals to get the X chromosome from the maternal side.[5] The lack of Y chromosome is why hybridization can occur between A. fasciatusand A. socius, because differences in genetics is limited to the X chromosome only.[5]

Females have a high affinity for the sperm that is presented by conspecific males, therefore if mating does occur with a heterospecific male, it rarely results in hybridized offspring.[6] She ultimately has the ability to mate in and outside of her own species, but her eggs will more often than not be fertilized by her conspecific male.[6]

Oviposition

A. fasciatus produces one brood in a season.[5] In the later part of the summer,[5] A. fasciatus deposits it's embryos into the ground through a reproductive structure called the ovipositor. [11] Ovipositor length in A. fasciatus varies depending on the geographical location it is found.[4] When A. fasciatus deposits her diapause egg in the ground, the depth at which the egg is deposited depends on the length of the ovipositor.[11] As diapause relies on temperature, it is possible that in high temperatures, eggs of A. fasciatus can exit or avoid the diapause phase, however this is not common.[5] Between the two sister species, at a temperature given of 30 degrees Celsius, A. fasciatus develops quicker than A. socius.[5]

A. fasciatus undergoes a process called bet hedging that is likely due to temperature and changes in moisture found in the soil where eggs are positioned.[12]

References

- Howard, D. J., and Waring, G. L. "Topographic Diversity, Zone Width, and the Strength of Reproductive Isolation in a Zone of Overlap and Hybridization." Evolution 45. (1991): 1120-1135.

- Birge, L. M., Hughes, A. L., Marshall, J. L., and Howard, D. J. "Mating Behaviour Differences and the Cost of Mating in Allonemobius fasciatus and A. socius." J Insect Behav 23 (2010): 268-289.

- "Allonemobius fasciatus Report". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- Mousseau, T. A. and Roff, D. A. "Geographic Variability in the Incidence and Heritability of Wing Dimorphism in the Striped Ground Cricket, Allonemobius fasciatus." Heredity 62 (1989): 315-318.

- Tanaka, Seiji. "Developmental Characteristics of Two Closely Related Species of Allonemobius and Their Hybrids" Oecologia (Berlin) 69 (1986): 388-394.

- Birge, L. M., Hughes, A. L., Marshall, J. L., and Howard, D. J. "Mating Behaviour Differences and the Cost of Mating in Allonemobius fasciatus and A. socius." J Insect Behav 23 (2010): 268-289.

- Mousseau, T. A. and Howard, D. J. "Genetic Variation in Cricket Calling Song across a Hybrid Zone between Two Sibling Species." Evolution 52 (1998): 1104-1110.

- Britch, S. C., Cain, L., and Howard, D. J. "Spatio-temporal dynamics of the Allonemobius fasciatus- A. socius Mosaic Hybrid Zone: A 14-year Perspective." Molecular Ecology 10 (2001): 627-638.

- Doherty, J. A. and Howard, D. J. "Lack of Preference for Conspecific Calling Songs in Female Crickets." Animal Behaviour 51 (1996): 981-990.

- Masaki, Shinzo. "Geographical Variation of Life Cycle in Crickets (Ensifera: Grylloidea)." European Journal of Entomology 93 (1996): 281-302.

- Mousseau, T. A. and Roff, D. A. "Does Natural Selection Alter Genetic Architecture? An Evaluation of Quantitative Genetic Variation Among Populations of Allonemobius socius and A. fasciatus." J. Evolutionary Biology. 12 (1999): 361-369.

- Bradford, M. J. and Roff, D. A. "Bet Hedging and the Diapause Strategies of the Cricket Allonemobius fasciatus." Ecology 74 (1993): 1129-1135.

External links

- "Allonemobius fasciatus". GBIF. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "Allonemobius fasciatus species Information". BugGuide.net. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- Otte, Daniel; Cigliano, Maria Marta; Braun, Holger; Eades, David C. (2019). "species Allonemobius fasciatus (De Geer, 1773)". Orthoptera species file online, Version 5.0. Retrieved 2019-07-02.