Amadu II of Masina

Amadu II of Massina (Fula: Amadu Amadu Hammadi;[lower-alpha 1] c. 1815 – February 1853[4]), also called Amadu Seku, was the second Almami, or ruler, of the theocratic Massina Empire or Diina of Hamdullahi in what is now Mali. He held this position from 1845 until his death in 1853. His rule was a short period of relative peace and prosperity between the violent reigns of his father and his son.

Amadu II of Massina | |

|---|---|

| Almami of the Massina Empire | |

| In office 1845–1852 | |

| Preceded by | Seku Amadu |

| Succeeded by | Amadu III |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Amadu Amadu Hammadi c. 1815 |

| Died | February 1853 |

| Occupation | Cleric |

Background

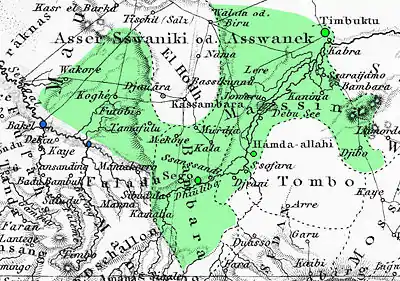

Masina is the Inner Niger Delta, a large area where the Niger River divides into separate channels that overflow and flood the land annually.[5] Some time between 1810 and 1818 Seku Amadu Lobbo of the Bari family launched a jihad against the Fulbe chiefs in Masina, tributaries of the pagan Bambara of Segu, whom he accused of idolatry.[6] The goals of the jihad soon expanded to that of conquest of the Bambara and others in the region. Seku Amadu established a large empire based on Hamdallahi, which he had founded as the capital.[7] The empire stretched from just downstream of Segu almost all the way to Timbuktu.[8]

Seku Amadu Lobbo received support from Tukolor and Fula people who were seeking independence from the Bambara, but met resistance when he imposed a rigorous Islamic theocracy based on the Maliki interpretation of Sharia law. The new theocratic state was ruled by a council of forty elders, who gave directions to provincial governors. Most of the governors were related to Seku Amadu.[9]

Rule

Seku Amadu Lobbo died on 19 March 1845 and his eldest son, also Amadu, was elected as almami. Technically, the new almami did not have to be a member of the Bari family, but only someone who was learned and pious.[10] There were several candidates, including Ba Lobbo, the son of Seku Amadu's oldest brother.[11] Election of Ba Lobbo would have followed the Bari family tradition of succession through a collateral line rather than direct succession.[12] Others such as Alfa Nuhum Tayru and al-Hadjdj Mody Seydu were better qualified, although not related to the former almami.[13] However, the council chose the son as almami, while Ba Lobbo became the main leader of the state's army.[11]

At the start of his rule, Amadu II (Amadu Seku) had to suppress internal opposition. He also faced revolts by the Saro Bambara and the Tuareg around Timbuktu, who declared independence. Ba Lobbo defeated the Tuareg with a surprise attack near Lake Gossi early in 1846. In 1847 the local Kunta leader, Sidi al-Bekkai, managed to persuade Amadu to withdraw his military garrison from Timbuktu, but had to accept Masina rule. Amadu was also able to suppress the Bambara revolt.[14]

Amadu's rule was a time of relative peace and prosperity compared to those of his father and his son, building on his father's achievement in persuading the formerly nomadic Fula people to settle, and in establishing a strong legal framework for grazing and transhumance rights.[15] However, Amadu found it hard to maintain the level of enthusiasm for strict Islamic rule that his father had achieved.[8]

Ahmadu II was killed during a raid on the Bambara.[16] He died in February 1853.[14] His tomb may still be seen in Hamdallahi, along with that of his father, in the ruins of the palace.[17]

Succession

Amadu II nominated his son, also Amadu, as his successor.[18] In 1853, Amadu III was elected to the position of Almami in accordance with his father's wishes.[2] Amadu III was handicapped by dissension over his succession within the Bari family, and was never secure in his authority.[12] Ahmadu III was defeated on 15 May 1862 by the jihadist el Hadj Umar Tall, who occupied Hamdallahi.[19] The Masina Empire had lasted little more than forty years.[20]

Notes and references

Notes

- Amadu Amadu Hammadi: Amadu was his given name. His father was Amadu and his grandfather was Hammadi. His family name was Bari. As with his father, the honorific "Seku" or "Shehu" (Sheikh) was often added before his given name, as "Seku Amadu".[1] He was also called "Amadu Seku".[2] This means "Amadu, son of the Sheikh" and implies a lesser status than the father.[3]

Citations

- Flint 1977, p. 151.

- Hunwick 2003, p. 212.

- Hanson 1996, p. 94.

- Robinson 1988, p. 270.

- Klein 1998, p. 46.

- Flint 1977, pp. 151–152.

- Flint 1977, p. 152.

- Austen 2010, p. 61.

- Flint 1977, p. 153.

- Ajayi 1989, p. 608.

- Levtzion 2012, p. 140.

- Robinson 1988, p. 271.

- Ajayi 1989, p. 608–609.

- Ajayi 1989, p. 609.

- Ajayi 1989, p. 605.

- Martin 2003, p. 92.

- Velton 2009, p. 172.

- Anene & Brown 1968, p. 302.

- Holt 1977, p. 378.

- Gaudio 2002, p. 134.

Sources

- Ajayi, Jacob F. Ade (1989). Africa in the Nineteenth Century Until the 1880s. University of California Press. p. 605. ISBN 978-0-520-03917-9. Retrieved 2013-03-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anene, Joseph C.; Brown, Godfrey Norman (1968). Africa in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: A Handbook for Teachers and Students. Ibadan University Press. ISBN 9780175112593. Retrieved 2013-03-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Austen, Ralph A. (2010-03-22). Trans-Saharan Africa in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979883-4. Retrieved 2013-03-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Flint, John E. (1977-01-20). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20701-0. Retrieved 2013-03-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaudio, Attilio (2002). Les bibliothèques du désert: recherches et études sur un millénaire d'écrits. Actes des colloques du CIRSS 1995-2000 (in French). Editions L'Harmattan. p. 134. ISBN 978-2-7475-1800-0. Retrieved 2013-03-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanson, John H. (1996). Migration, Jihad, and Muslim Authority in West Africa: The Futanke Colonies in Karta. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33088-8. Retrieved 2013-03-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann K. S.; Lewis, Bernard (1977-04-21). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29137-8. Retrieved 2013-03-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunwick, John O. (2003-06-01). Arabic Literature of Africa. BRILL. p. 212. ISBN 978-90-04-12444-8. Retrieved 2013-03-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klein, Martin A. (1998-07-28). Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59678-7. Retrieved 2013-03-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levtzion, Nehemia (2012-09-21). History Of Islam In Africa. Ohio University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-8214-4461-0. Retrieved 2013-03-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, B. G. (2003-02-13). Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-521-53451-2. Retrieved 2013-03-04.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, David (1988). La Guerre sainte d'Al-Hajj Umar: le Soudan occidental au milieu du XIXe siècle (in French). KARTHALA Editions. p. 270. ISBN 978-2-86537-211-9. Retrieved 2013-03-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Velton, Ross (2009-11-24). Mali: the Bradt safari guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-84162-218-7. Retrieved 2013-03-10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)