Ancient Egyptian race controversy

The question of the race of ancient Egyptians was raised historically as a product of the early racial concepts of the 18th and 19th centuries, and was linked to models of racial hierarchy primarily based on craniometry and anthropometry. A variety of views circulated about the racial identity of the Egyptians and the source of their culture.[1] Some scholars argued that ancient Egyptian culture was influenced by other Afroasiatic-speaking populations in North Africa or the Middle East, while others pointed to influences from various Nubian groups or populations in Europe. In more recent times some writers continued to challenge the mainstream view, some focusing on questioning the race of specific notable individuals such as the king represented in the Great Sphinx of Giza, native Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun, Egyptian Queen Tiye, and Greek Ptolemaic queen Cleopatra VII.

Mainstream scholars reject the notion that Egypt was a white or black civilization; they maintain that, despite the phenotypic diversity of Ancient and present-day Egyptians, applying modern notions of black or white races to ancient Egypt is anachronistic.[2][3][4] In addition, scholars reject the notion, implicit in the notion of a black or white Egypt hypothesis, that Ancient Egypt was racially homogeneous; instead, skin color varied between the peoples of Lower Egypt, Upper Egypt, and Nubia, who in various eras rose to power in Ancient Egypt. Moreover, "Most scholars believe that Egyptians in antiquity looked pretty much as they look today, with a gradation of darker shades toward the Sudan".[5] Within Egyptian history, despite multiple foreign invasions, the demographics were not shifted by large migrations.[5][6][7]

Origins

The earliest examples of disagreement regarding the race of the ancient Egyptians occurred in the work of Europeans and Americans early in the 19th century. One early example of such an attempt was an article published in The New-England Magazine of October 1833, where the authors dispute a claim that "Herodotus was given as authority for their being negroes." They point out with reference to tomb paintings: "It may be observed that the complexion of the men is invariably red, that of the women yellow; but neither of them can be said to have anything in their physiognomy at all resembling the Negro countenance."[8]

In the 18th century, Constantin François de Chassebœuf, comte de Volney, wrote about the race controversy. In one translation, he wrote "The Copts are the proper representatives of the Ancient Egyptians" due to their "jaundiced and fumed skin, which is neither Greek, Negro nor Arab, their full faces, their puffy eyes, their crushed noses, and their thick lips...the ancient Egyptians were true negroes of the same type as all native born Africans".[9][10] In another translation, Volney said the Sphinx gave him the key to the riddle, "seeing that head, typically negro in all its features",[11]:27 the Copts were "true negroes of the same stock as all the autochthonous peoples of Africa" and they "after some centuries of mixing..., must have lost the full blackness of its original color."[12]:26

Just a few years later, in 1839, Jean-François Champollion stated in his work Egypte Ancienne that the Egyptians and Nubians are represented in the same manner in tomb paintings and reliefs, further suggesting that: "In the Copts of Egypt, we do not find any of the characteristic features of the ancient Egyptian population. The Copts are the result of crossbreeding with all the nations that successfully dominated Egypt. It is wrong to seek in them the principal features of the old race."[13] Also in 1839, Champollion's and Volney's claims were disputed by Jacques Joseph Champollion-Figeac, who blamed the ancients for spreading a false impression of a Negro Egypt, stating "the two physical traits of black skin and kinky hair are not enough to stamp a race as negro"[12]:26and "the opinion that the ancient population of Egypt belonged to the Negro African race, is an error long accepted as the truth. ... Volney's conclusion as to the Negro origin of the ancient Egyptian civilization is evidently forced and inadmissible."[14]

Foster summarized the early 19th century "controversy over the ethnicity of the ancient Egyptians" as a debate of conflicting theories regarding the Hamites. "In ancient times, the Hamites, who developed the civilization of Egypt, were considered Black."[15] Foster describes the 6th century CE curse of Ham theory, which began "in the Babylonian Talmud, a collection of oral traditions of the Jews, that the sons of Ham are cursed by being black."[15] Foster said "throughout the Middle Ages and to the end of the eighteenth century, the Negro was seen by Europeans as a descendant of Ham."[15] In the early 19th century, "after Napolean's expedition to Egypt, the Hamites began to be viewed as having been Caucasians."[15] However, "Napolean's scientists concluded that the Egyptians were Negroid." Napoleon's colleagues referenced prior "well-known books" by Constantin François de Chassebœuf, comte de Volney and Vivant Denon that described Ancient Egyptians as "negroid.".[15] Finally, Foster concludes, "it was at this point that Egypt became the focus of much scientific and lay interest, the result of which was the appearance of many publications whose sole purpose was to prove that the Egyptians were not Black, and therefore capable of developing such a high civilization."[15]

The debate over the race of the ancient Egyptians intensified during the 19th century movement to abolish slavery in the United States, as arguments relating to the justifications for slavery increasingly asserted the historical, mental and physical inferiority of black people. For example, in 1851, John Campbell directly challenged the claims by Champollion and others regarding the evidence for a black Egypt, asserting "There is one great difficulty, and to my mind an insurmountable one, which is that the advocates of the negro civilization of Egypt do not attempt to account for, how this civilization was lost.... Egypt progressed, and why, because it was Caucasian."[16] The arguments regarding the race of the Egyptians became more explicitly tied to the debate over slavery in the United States, as tensions escalated towards the American Civil War.[17] In 1854, Josiah C. Nott with George Glidden set out to prove: "that the Caucasian or white, and the Negro races were distinct at a very remote date, and that the Egyptians were Caucasians."[18] Samuel George Morton, a physician and professor of anatomy, concluded that although "Negroes were numerous in Egypt, but their social position in ancient times was the same that it now is [in the United States], that of servants and slaves."[19] In the early 20th century, Flinders Petrie, a professor of Egyptology at the University of London, in turn spoke of "a black queen",[20] Ahmose-Nefertari, who was the "divine ancestress of the XVIIIth dynasty". He described her physically as "the black queen Aohmes Nefertari had an aquiline nose, long and thin, and was of a type not in the least prognathous".[21]

Position of modern scholarship

Modern scholars who have studied ancient Egyptian culture and population history have responded to the controversy over the race of the ancient Egyptians in different ways.

At the UNESCO "Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script" in Cairo in 1974, the Black Hypothesis met with "profound" disagreement by scholars.[22] Similarly, none of the participants voiced support for an earlier theory where Egyptians were "white with a dark, even black, pigmentation."[12]:43 The arguments for all sides are recorded in the UNESCO publication General History of Africa,[23] with the "Origin of the Egyptians" chapter being written by the proponent of the black hypothesis Cheikh Anta Diop. At the 1974 UNESCO conference, most participants concluded that the ancient Egyptian population was indigenous to the Nile Valley, and was made up of people from north and south of the Sahara who were differentiated by their color.[24]

Since the second half of the 20th century, most anthropologists have rejected the notion of race as having any validity in the study of human biology.[25][26] Stuart Tyson Smith writes in the 2001 Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, "Any characterization of race of the ancient Egyptians depends on modern cultural definitions, not on scientific study. Thus, by modern American standards it is reasonable to characterize the Egyptians as 'black', while acknowledging the scientific evidence for the physical diversity of Africans."[27] Frank M. Snowden asserts "Egyptians, Greeks and Romans attached no special stigma to the colour of the skin and developed no hierarchical notions of race whereby highest and lowest positions in the social pyramid were based on colour."[28][29]

Barbara Mertz writes in Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt: "Egyptian civilization was not Mediterranean or African, Semitic or Hamitic, black or white, but all of them. It was, in short, Egyptian."[30] Kathryn Bard, Professor of Archaeology and Classical Studies, wrote in Ancient Egyptians and the issue of race that "Egyptians were the indigenous farmers of the lower Nile valley, neither black nor white as races are conceived of today".[31] Nicky Nielsen wrote in Egyptomaniacs: How We Became Obsessed with Ancient Egypt that "Ancient Egypt was neither black nor white, and the repeated attempt by advocates of either ideology to seize the ownership of ancient Egypt simply perpetuates an old tradition: one of removing agency and control of their heritage from the modern population living along the banks of the Nile."[32]

Frank J. Yurco, an Egyptologist at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago, said: "When you talk about Egypt, it's just not right to talk about black or white, That's all just American terminology and it serves American purposes. I can understand and sympathize with the desires of Afro-Americans to affiliate themselves with Egypt. But it isn't that simple [..] To take the terminology here {in the United States} and graft it onto Africa is anthropologically inaccurate". Yurco added that "We are applying a racial divisiveness to Egypt that they would never have accepted, They would have considered this argument absurd, and that is something we could really learn from."[33] Yurco writes that "the peoples of Egypt, the Sudan, and much of North-East Africa are generally regarded as a Nilotic continuity, with widely ranging physical features (complexions light to dark, various hair and craniofacial types)".[34]

Barry J. Kemp argues that the black/white argument, though politically understandable, is an oversimplification that hinders an appropriate evaluation of the scientific data on the ancient Egyptians since it does not take into consideration the difficulty in ascertaining complexion from skeletal remains. It also ignores the fact that Africa is inhabited by many other populations besides Bantu-related ("Negroid") groups. He asserts that in reconstructions of life in ancient Egypt, modern Egyptians would therefore be the most logical and closest approximation to the ancient Egyptians.[35] In 2008, S. O. Y. Keita wrote that "There is no scientific reason to believe that the primary ancestors of the Egyptian population emerged and evolved outside of northeast Africa.... The basic overall genetic profile of the modern population is consistent with the diversity of ancient populations that would have been indigenous to northeastern Africa and subject to the range of evolutionary influences over time, although researchers vary in the details of their explanations of those influences."[36] According to Bernard R. Ortiz De Montellano, "the claim that all Egyptians, or even all the pharaohs, were black, is not valid. Most scholars believe that Egyptians in antiquity looked pretty much as they look today, with a gradation of darker shades toward the Sudan".[5]

Near-Eastern genetic affinity of Egyptian mummies

A study published in 2017 by Schuenemann et al described the extraction and analysis of DNA from 151 mummified ancient Egyptian individuals, whose remains were recovered from a site near the modern village of Abusir el-Meleq in Middle Egypt, near the Faiyum Oasis.[37][38] The area of Abusir el-Meleq, near El Fayum, was inhabited from at least 3250 BCE until about 700 CE.[39] The scientists said that obtaining well-preserved, uncontaminated DNA from mummies has been a problem for the field and that these samples provided "the first reliable data set obtained from ancient Egyptians using high-throughput DNA sequencing methods".[38]

The study was able to measure the mitochondrial DNA of 90 individuals, and it showed that the mitochondrial DNA composition of Egyptian mummies has shown a high level of affinity with the DNA of the populations of the Near East.[37][38] Genome-wide data could only be successfully extracted from three of these individuals. Of these three, the Y-chromosome haplogroups of two individuals could be assigned to the Middle-Eastern haplogroup J, and one to haplogroup E1b1b1 common in North Africa. The absolute estimates of sub-Saharan African ancestry in these three individuals ranged from 6 to 15%, which is significantly lower than the level of sub-Saharan African ancestry in the modern Egyptians from Abusir el-Meleq, who "range from 14 to 21%." The study's authors cautioned that the mummies may be unrepresentative of the Ancient Egyptian population as a whole.[40]

A shared drift and mixture analysis of the DNA of these ancient Egyptian mummies shows that the connection is strongest with ancient populations from the Levant, the Near East and Anatolia, and to a lesser extent modern populations from the Near East and the Levant.[38] In particular the study finds "that ancient Egyptians are most closely related to Neolithic and Bronze Age samples in the Levant, as well as to Neolithic Anatolian populations".[39] However, the study showed that comparative data from a contemporary population under Roman rule in Anatolia, did not reveal a closer relationship to the ancient Egyptians from the same period. furthermore, "Genetic continuity between ancient and modern Egyptians cannot be ruled out despite this sub-Saharan African influx, while continuity with modern Ethiopians is not supported".[38]

The current position of modern scholarship is that the Ancient Egyptian civilization was an indigenous Nile Valley development (see population history of Egypt).[41][42][43][44]

Keita, Gourdine, and Anselin challenged the assertions in the 2017 study. They state the study is missing 3000 years of Ancient Egypt's history, fails to include indigenous Nile valley Nubians as a comparison group, only includes New Kingdom and newer Northern Egyptian individuals, and incorrectly classifies "all mitochondrial M1 haplogroups as "Asian" which is problematic."[45] Keita et al. states, "M1 has been postulated to have emerged in Africa; many M1 daughter haplogroups (M1a) are clearly African in origin and history."[45] In conclusion, Keita/Gourdine state due to the small sample size (2.4% of Egypt's nomes), the "Schuenemann et al. study is best seen as a contribution to understanding a local population history in northern Egypt as opposed to a population history of all Egypt from its inception."[45]

Professor Stephen Quirke, an Egyptologist at University College London, expressed caution about the researchers’ broader claims, saying that “There has been this very strong attempt throughout the history of Egyptology to disassociate ancient Egyptians from the modern population.” He added that he was “particularly suspicious of any statement that may have the unintended consequences of asserting – yet again from a northern European or North American perspective – that there’s a discontinuity there [between ancient and modern Egyptians]".[46]

Ancient Egyptian genetic studies

A number of scientific papers have reported, based on both maternal and paternal genetic evidence, that a substantial back-flow of people took place from Eurasia into North-east Africa, including Egypt, around 30,000 years before the start of the Dynastic period.[47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

Some authors have offered a theory that the M haplogroup may have developed in Africa before the 'Out of Africa' event around 50,000 years ago, and dispersed in Africa from East Africa 10,000 to 20,000 years ago.[60]:85–88 [61][62][63]

Specific current-day controversies

Today the issues regarding the race of the ancient Egyptians are "troubled waters which most people who write about ancient Egypt from within the mainstream of scholarship avoid."[64] The debate, therefore, takes place mainly in the public sphere and tends to focus on a small number of specific issues.

Tutankhamun

Several scholars, including Diop, have claimed that Tutankhamun was black, and have protested that attempted reconstructions of Tutankhamun's facial features (as depicted on the cover of National Geographic magazine) have represented the king as "too white". Among these writers was Chancellor Williams, who argued that King Tutankhamun, his parents, and grandparents were black.[65]

Forensic artists and physical anthropologists from Egypt, France, and the United States independently created busts of Tutankhamun, using a CT-scan of the skull. Biological anthropologist Susan Anton, the leader of the American team, said the race of the skull was "hard to call". She stated that the shape of the cranial cavity indicated an African, while the nose opening suggested narrow nostrils, which is usually considered to be a European characteristic. The skull was thus concluded to be that of a North African.[66] Other experts have argued that neither skull shapes nor nasal openings are a reliable indication of race.[67]

Although modern technology can reconstruct Tutankhamun's facial structure with a high degree of accuracy, based on CT data from his mummy,[68][69] determining his skin tone and eye color is impossible. The clay model was therefore given a coloring, which, according to the artist, was based on an "average shade of modern Egyptians".[70]

Terry Garcia, National Geographic's executive vice president for mission programs, said, in response to some of those protesting against the Tutankhamun reconstruction:

The big variable is skin tone. North Africans, we know today, had a range of skin tones, from light to dark. In this case, we selected a medium skin tone, and we say, quite up front, 'This is midrange.' We will never know for sure what his exact skin tone was or the color of his eyes with 100% certainty.... Maybe in the future, people will come to a different conclusion.[71]

When pressed on the issue by American activists in September 2007, the Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, Zahi Hawass stated "Tutankhamun was not black."[72]

In a November 2007 publication of Ancient Egypt magazine, Hawass asserted that none of the facial reconstructions resemble Tut and that, in his opinion, the most accurate representation of the boy king is the mask from his tomb.[73] The Discovery Channel commissioned a facial reconstruction of Tutankhamun, based on CT scans of a model of his skull, back in 2002.[74][75]

In 2011, the genomics company iGENEA launched a Tutankhamun DNA project based on genetic markers that it indicated it had culled from a Discovery Channel special on the pharaoh. According to the firm, the microsatellite data suggested that Tutankhamun belonged to the haplogroup R1b1a2, the most common paternal clade among males in Western Europe. Carsten Pusch and Albert Zink, who led the unit that had extracted Tutankhamun's DNA, chided iGENEA for not liaising with them before establishing the project. After examining the footage, they also concluded that the methodology the company used was unscientific with Putsch calling them "simply impossible".[76]

Cleopatra

The race and skin color of Cleopatra VII, the last active Hellenistic ruler of the Macedonian Greek Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt, established in 323 BCE, has also caused some debate,[77] although generally not in scholarly sources.[78] For example, the article "Was Cleopatra Black?" was published in Ebony magazine in 2012,[79] and an article about Afrocentrism from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch mentions the question, too.[80] Mary Lefkowitz, Professor Emerita of Classical Studies at Wellesley College, traces the origins of the black Cleopatra claim to the 1872 book by J.A. Rogers called "World's Great Men of Color."[81][82] Lefkowitz refutes Rogers' hypothesis, on various scholarly grounds. The black Cleopatra claim was further revived in an essay by afrocentrist John Henrik Clarke, chair of African history at Hunter College, entitled "African Warrior Queens."[83] Lefkowitz notes the essay includes the claim that Cleopatra described herself as black in the New Testament's Book of Acts – when in fact Cleopatra had died more than sixty years before the death of Jesus Christ.[83]

Scholars identify Cleopatra as essentially of Greek ancestry with some Persian and Syrian ancestry, based on the fact that her Macedonian Greek family (the Ptolemaic dynasty) had intermingled with the Seleucid aristocracy of the time.[85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95] Grant states that Cleopatra probably had not a drop of Egyptian blood and that she "would have described herself as Greek."[96] Roller notes that "there is absolutely no evidence" that Cleopatra was racially black African as claimed by what he dismisses as generally not "credible scholarly sources."[97] Cleopatra's official coinage (which she would have approved) and the three portrait busts of her which are considered authentic by scholars, all match each other, and they portray Cleopatra as a Greek woman.[98][99][100][101] Polo writes that Cleopatra's coinage presents her image with certainty, and asserts that the sculpted portrait of the "Berlin Cleopatra" head is confirmed as having a similar profile.[99]

In 2009, a BBC documentary speculated that Cleopatra might have been part North African. This was based largely on the claims of Hilke Thür of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, who in the 1990s had examined a headless skeleton of a female child in a 20 BCE tomb in Ephesus (modern Turkey), together with the old notes and photographs of the now-missing skull. Thür hypothesized the body as that of Arsinoe, half-sister to Cleopatra.[102][103] Arsinoe and Cleopatra shared the same father (Ptolemy XII Auletes) but had different mothers,[104] with Thür claiming the alleged African ancestry came from the skeleton's mother. To date it has never been definitively proved that the skeleton is that of Arsinoe IV. Furthermore, craniometry as used by Thür to determine race is based in scientific racism that is now generally considered a pseudoscience that supported "exploitation of groups of people" to "perpetuate racial oppression" and "distorted future views of the biological basis of race."[105] When a DNA test attempted to determine the identity of the child, it was impossible to get an accurate reading since the bones had been handled too many times,[106] and the skull had been lost in Germany during World War II. Mary Beard states that the age of the skeleton is too young to be that of Arsinoe (the bones said to be that of a 15–18-year-old child, with Arsinoe being around her mid twenties at her death).[107]

Great Sphinx of Giza

The identity of the model for the Great Sphinx of Giza is unknown.[108] Most Egyptologists and scholars[109] currently believe that the face of the Sphinx represents the likeness of the Pharaoh Khafra, although a few Egyptologists and interested amateurs have proposed several different hypotheses.

An early description of the Sphinx, "typically negro in all its features", is recorded in the travel notes of a French scholar, Volney, who visited in Egypt between 1783 and 1785[110] along with French novelist Gustave Flaubert.[111] A similar description was given in the "well-known book"[15] by Vivant Denon, where he described the sphinx as "the character is African; but the mouth, the lips of which are thick."[112] Following Volney, Denon, and other early writers, numerous Afrocentric scholars, such as Du Bois,[113][114][115] Diop[116] and Asante[117] have characterized the face of the Sphinx as Black, or "Negroid".

American geologist Robert M. Schoch has written that the "Sphinx has a distinctive African, Nubian, or Negroid aspect which is lacking in the face of Khafre".[118][119] but he was described by others such as Ronald H. Fritze and Mark Lehner of being a "pseudoscientific writer".[120][121] David S. Anderson writes in Lost City, Found Pyramid: Understanding Alternative Archaeologies and Pseudoscientific Practices that Van Sertima's claim that "the sphinx was a portrait statue of the black pharoah Khafre" is a form of "pseudoarchaeology" not supported by evidence.[122] He compares it to the claim that Olmec colossal heads had "African origins", which is not taken seriously by Mesoamerican scholars such as Richard Diehl and Ann Cyphers.[123]

Kemet

| km biliteral | kmt (place) | kmt (people) | |||||||||

Ancient Egyptians referred to their homeland as Kmt (conventionally pronounced as Kemet). According to Cheikh Anta Diop, the Egyptians referred to themselves as "Black" people or kmt, and km was the etymological root of other words, such as Kam or Ham, which refer to Black people in Hebrew tradition.[12]:27[124] A review of David Goldenberg's The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity and Islam states that Goldenberg "argues persuasively that the biblical name Ham bears no relationship at all to the notion of blackness and as of now is of unknown etymology".[125] Diop,[126] William Leo Hansberry,[126] and Aboubacry Moussa Lam[127] have argued that kmt was derived from the skin color of the Nile valley people, which Diop claimed was black.[12]:21,26 The claim that the ancient Egyptians had black skin has become a cornerstone of Afrocentric historiography.[126]

Mainstream scholars hold that kmt means "the black land" or "the black place", and that this is a reference to the fertile black soil that was washed down from Central Africa by the annual Nile inundation. By contrast the barren desert outside the narrow confines of the Nile watercourse was called dšrt (conventionally pronounced deshret) or "the red land".[126][128] Raymond Faulkner's Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian translates kmt into "Egyptians",[129] Gardiner translates it as "the Black Land, Egypt".[130]

At the UNESCO Symposium in 1974, Sauneron, Obenga, and Diop concluded that KMT and KM meant black.[12]:40 However, Sauneron clarified that the adjective Kmtyw means "people of the black land" rather than "black people", and that the Egyptians never used the adjective Kmtyw to refer to the various black peoples they knew of, they only used it to refer to themselves.[131]

Ancient Egyptian art

Ancient Egyptian tombs and temples contained thousands of paintings, sculptures, and written works, which reveal a great deal about the people of that time. However, their depictions of themselves in their surviving art and artifacts are rendered in sometimes symbolic, rather than realistic, pigments. As a result, ancient Egyptian artifacts provide sometimes conflicting and inconclusive evidence of the ethnicity of the people who lived in Egypt during dynastic times.[132][133]

In their own art, "Egyptians are often represented in a color that is officially called dark red", according to Diop.[11]:48 Arguing against other theories, Diop quotes Champollion-Figeac, who states, "one distinguishes on Egyptian monuments several species of blacks, differing...with respect to complexion, which makes Negroes black or copper-colored."[11]:55 Regarding an expedition by King Sesostris, Cherubini states the following concerning captured southern africans, "except for the panther skin about their loins, are distinguished by their color, some entirely black, others dark brown.[11]:58–59 University of Chicago scholars assert that Nubians are generally depicted with black paint, but the skin pigment used in Egyptian paintings to refer to Nubians can range "from dark red to brown to black".[134] This can be observed in paintings from the tomb of the Egyptian Huy, as well as Ramses II's temple at Beit el-Wali.[135] Also, Snowden indicates that Romans had accurate knowledge of "negroes of a red, copper-colored complexion ... among African tribes".[136]

Conversely, Najovits states "Egyptian art depicted Egyptians on the one hand and Nubians and other blacks on the other hand with distinctly different ethnic characteristics and depicted this abundantly and often aggressively. The Egyptians accurately, arrogantly and aggressively made national and ethnic distinctions from a very early date in their art and literature."[137] He continues, "There is an extraordinary abundance of Egyptian works of art which clearly depicted sharply contrasted reddish-brown Egyptians and black Nubians."[137]

Barbara Mertz writes in Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt: "The concept of race would have been totally alien to them [Ancient Egyptians] [..]The skin color that painters usually used for men is a reddish brown. Women were depicted as lighter in complexion,[138] perhaps because they didn’t spend so much time out of doors. Some individuals are shown with black skins. I cannot recall a single example of the words “black,” “brown,” or “white” being used in an Egyptian text to describe a person." She gives the example of one of Thutmose III’s “sole companions”, who was Nubian or Cushite. In his funerary scroll, he is shown with dark brown skin instead of the conventional reddish brown used for Egyptians.[30]

Table of Nations controversy

However, Manu Ampim, a professor at Merritt College specializing in African and African American history and culture, claims in the book Modern Fraud: The Forged Ancient Egyptian Statues of Ra-Hotep and Nofret, that many ancient Egyptian statues and artworks are modern frauds that have been created specifically to hide the "fact" that the ancient Egyptians were black, while authentic artworks that demonstrate black characteristics are systematically defaced or even "modified". Ampim repeatedly makes the accusation that the Egyptian authorities are systematically destroying evidence that "proves" that the ancient Egyptians were black, under the guise of renovating and conserving the applicable temples and structures. He further accuses "European" scholars of wittingly participating in and abetting this process.[139][140]

Ampim has a specific concern about the painting of the "Table of Nations" in the Tomb of Ramesses III (KV11). The "Table of Nations" is a standard painting that appears in a number of tombs, and they were usually provided for the guidance of the soul of the deceased.[132][141] Among other things, it described the "four races of men" as follows: (translation by E.A. Wallis Budge)[141] "The first are RETH, the second are AAMU, the third are NEHESU, and the fourth are THEMEHU. The RETH are Egyptians, the AAMU are dwellers in the deserts to the east and north-east of Egypt, the NEHESU are the black races, and the THEMEHU are the fair-skinned Libyans."

The archaeologist Karl Richard Lepsius documented many ancient Egyptian tomb paintings in his work Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien.[142] In 1913, after the death of Lepsius, an updated reprint of the work was produced, edited by Kurt Sethe. This printing included an additional section, called the "Ergänzungsband" in German, which incorporated many illustrations that did not appear in Lepsius' original work. One of them, plate 48, illustrated one example of each of the four "nations" as depicted in KV11, and shows the "Egyptian nation" and the "Nubian nation" as identical to each other in skin color and dress. Professor Ampim has declared that plate 48 is a true reflection of the original painting, and that it "proves" that the ancient Egyptians were identical in appearance to the Nubians, even though he admits no other examples of the "Table of Nations" show this similarity. He has further accused "Euro-American writers" of attempting to mislead the public on this issue.[143]

The late Egyptologist Frank J. Yurco visited the tomb of Ramesses III (KV11), and in a 1996 article on the Ramesses III tomb reliefs he pointed out that the depiction of plate 48 in the Ergänzungsband section is not a correct depiction of what is actually painted on the walls of the tomb. Yurco notes, instead, that plate 48 is a "pastiche" of samples of what is on the tomb walls, arranged from Lepsius' notes after his death, and that a picture of a Nubian person has erroneously been labeled in the pastiche as an Egyptian person. Yurco points also to the much more recent photographs of Dr. Erik Hornung as a correct depiction of the actual paintings.[144] (Erik Hornung, The Valley of the Kings: Horizon of Eternity, 1990). Ampim nonetheless continues to claim that plate 48 shows accurately the images that stand on the walls of KV11, and he categorically accuses both Yurco and Hornung of perpetrating a deliberate deception for the purposes of misleading the public about the true race of the ancient Egyptians.[143]

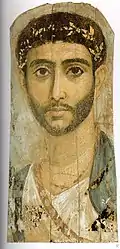

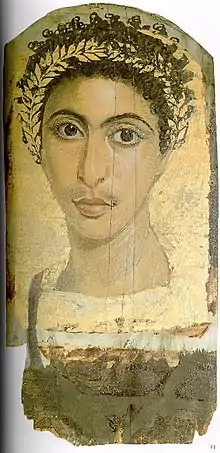

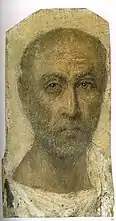

Fayyum mummy portraits

The Roman era Fayum mummy portraits attached to coffins containing the latest dated mummies discovered in the Faiyum Oasis represent a population of both native Egyptians and those with mixed Greek heritage.[145] The dental morphology of the mummies align more with the indigenous North African population than Greek or other later colonial European settlers.[146]

Black queen controversy

The late British Africanist Basil Davidson stated "Whether the Ancient Egyptians were as black or as brown in skin color as other Africans may remain an issue of emotive dispute; probably, they were both. Their own artistic conventions painted them as pink, but pictures on their tombs show they often married queens shown as entirely black[20] being from the south."[147] Yaacov Shavit wrote that "Egyptian men have a reddish complexion, while Egyptian women have a clear yellowish cast; and moreover there are almost no black women in the many wall paintings."[148]

Ahmose-Nefertari is an example. In most depictions of Ahmose-Nefertari, she is pictured with black skin,[149][150] while in some instances her skin is blue[151] or red.[152] In 1939 Flinders Petrie said "an invasion from the south...established a black queen as the divine ancestress of the XVIIIth dynasty"[153][20] He also said "a possibility of the black being symbolic has been suggested"[153] and "Nefertari must have married a Libyan, as she was the mother of Amenhetep I, who was of fair Libyan style."[153] In 1961 Alan Gardiner, in describing the walls of tombs in the Deir el-Medina area, noted in passing that Ahmose-Nefertari was "well represented" in these tomb illustrations, and that her countenance was sometimes black and sometimes blue. He did not offer any explanation for these colors, but noted that her probable ancestry ruled out that she might have had black blood.[151] In 1974, Diop described Ahmose-Nefertari as "typically negroid."[12]:17 In the controversial book Black Athena, the hypotheses of which have been widely rejected by mainstream scholarship, Martin Bernal considered her skin color in paintings to be a clear sign of Nubian ancestry.[154] In more recent times, scholars such as Joyce Tyldesley, Sigrid Hodel-Hoenes, and Graciela Gestoso Singer, argued that her skin color is indicative of her role as a goddess of resurrection, since black is both the color of the fertile land of Egypt and that of Duat, the underworld.[149] Singer recognizes that "Some scholars have suggested that this is a sign of Nubian ancestry."[149] Singer also states a statuette of Ahmose-Nefertari at the Museo Egizio in Turin which shows her with a black face, though her arms and feet are not darkened, thus suggesting that the black coloring has an iconographic motive and does not reflect her actual appearance.[155]:90[156][149]

Queen Tiye is another example of the controversy. American journalists Michael Specter, Felicity Barringer, and others describe one of her sculptures as that of a "black African".[157][158][159] Egyptologist Frank J. Yurco has examined her mummy, which he described as having 'long, wavy brown hair, a high-bridged, arched nose and moderately thin lips."[158]

Historical hypotheses

Since the second half of the 20th century, typological and hierarchical models of race have increasingly been rejected by scientists, and most scholars have held that applying modern notions of race to ancient Egypt is anachronistic.[160][161][162] The current position of modern scholarship is that the Egyptian civilization was an indigenous Nile Valley development (see population history of Egypt).[41][42][43][44] At the UNESCO symposium in 1974, most participants concluded that the ancient Egyptian population was indigenous to the Nile Valley, and was made up of people from north and south of the Sahara who were differentiated by their color.[24]

Black Egyptian hypothesis

The Black Egyptian hypothesis, which has been rejected by mainstream scholarship, is the hypothesis that ancient Egypt was indigenous to Africa and a Black civilization.[11]:1,27,43,51[163] Although there is consensus that Ancient Egypt was indigenous to Africa, the hypothesis that Ancient Egypt was a "black civilization" has met with "profound" disagreement.[164]

The Black Egyptian hypothesis includes a particular focus on links to Sub Saharan cultures and the questioning of the race of specific notable individuals from Dynastic times, including Tutankhamun[165] the person represented in the Great Sphinx of Giza,[11]:1,27,43,51[166][167] and the Greek Ptolemaic queen Cleopatra.[168][169][170][171] Advocates of the Black African model rely heavily on writings from Classical Greek historians, including Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and Herodotus. Advocates claim that these "classical" authors referred to Egyptians as "Black with woolly hair".[172][11]:1,27,43,51,278,288[173]:316–321[163]:52–53[174]:21 The Greek word used was "melanchroes", and the English language translation of this Greek word is disputed, being translated by many as "dark skinned"[175][176] and by many others as "black".[11]:1,27,43,51,278,288[163]:52–53[174]:15–60[177][178] Diop said "Herodotus applied melanchroes to both Ethiopians and Egyptians...and melanchroes is the strongest term in Greek to denote blackness."[11]:241–242 Snowden claims that Diop is distorting his classical sources and is quoting them selectively.[179] There is dispute about the historical accuracy of the works of Herodotus – some scholars support the reliability of Herodotus[11]:2–5[180]:1[181][182][183][184] while other scholars regard his works as being unreliable as historical sources, particularly those relating to Egypt.[185][186][187][188][189][190][191][192][193][194][195]

Other claims used to support the Black Hypothesis included testing melanin levels in a small sample of mummies,[12]:20,37[11]:236–243 language affinities between ancient Egyptian language and sub-saharan languages,[12]:28,39–41,54–55[196] interpretations of the origin of the name Kmt, conventionally pronounced Kemet, used by the ancient Egyptians to describe themselves or their land (depending on points of view),[12]:27,38,40 biblical traditions,[197][12]:27–28 shared B blood group between Egyptians and West Africans,[12]:37 and interpretations of the depictions of the Egyptians in numerous paintings and statues.[11]:6–42 The hypothesis also claimed cultural affiliations, such as circumcision,[11]:112, 135–138 matriarchy, totemism, hair braiding, head binding,[198] and kingship cults.[11]:1–9,134–155 Artifacts found at Qustul (near Abu Simbel – Modern Sudan) in 1960–64 were seen as showing that ancient Egypt and the A-Group culture of Nubia shared the same culture and were part of the greater Nile Valley sub-stratum,[199][200][201][202][203] but more recent finds in Egypt indicate that the Qustul rulers probably adopted/emulated the symbols of Egyptian pharaohs.[204][205][206][207][208][209] Authors and critics state the hypothesis is primarily adopted by Afrocentrists.[210][211][212][213][214][215][216][217]

At the UNESCO "Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic script" in Cairo in 1974, there was consensus that Ancient Egypt was indigenous to Africa, but the Black Hypothesis met with "profound" disagreement.[164] The current position of modern scholarship is that the Egyptian civilization was an indigenous Nile Valley development (see population history of Egypt).[41][42][43][44]

Asiatic race theory

The Asiatic race theory, which has been rejected by mainstream scholarship, is the hypothesis that the ancient Egyptians were the lineal descendants of the biblical Ham, through his son Mizraim.

This theory was the most dominant view from the Early Middle Ages (c. 500 AD) all the way up to the early 19th century.[218][219][15] The descendants of Ham were traditionally considered to be the darkest-skinned branch of humanity, either because of their geographic allotment to Africa or because of the Curse of Ham.[220][15] Thus, Diop cites Gaston Maspero "Moreover, the Bible states that Mesraim, son of Ham, brother of Chus (Kush) ... and of Canaan, came from Mesopotamia to settle with his children on the banks of the Nile."[11]:5–9

By the 20th century, the Asiatic race theory and its various offshoots were abandoned but were superseded by two related theories: the Eurocentric Hamitic hypothesis, asserting that a Caucasian racial group moved into North and East Africa from early prehistory subsequently bringing with them all advanced agriculture, technology and civilization, and the Dynastic race theory, proposing that Mesopotamian invaders were responsible for the dynastic civilization of Egypt (c. 3000 BC). In sharp contrast to the Asiatic race theory, neither of these theories proposes that Caucasians were the indigenous inhabitants of Egypt.[221]

At the UNESCO "Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script" in Cairo in 1974, none of the participants explicitly voiced support for any theory where Egyptians were Caucasian with a dark pigmentation.".[12]:43[23] The current position of modern scholarship is that the Egyptian civilization was an indigenous Nile Valley development (see population history of Egypt).[41][42][43][44]

Caucasian / Hamitic hypothesis

The Caucasian hypothesis, which has been rejected by mainstream scholarship, is the hypothesis that the Nile valley "was originally peopled by a branch of the Caucasian race".[222] It was proposed in 1844 by Samuel George Morton, who acknowledged that Negroes were present in ancient Egypt but claimed they were either captives or servants.[223] George Gliddon (1844) wrote: "Asiatic in their origin .... the Egyptians were white men, of no darker hue than a pure Arab, a Jew, or a Phoenician."[224]

The similar Hamitic hypothesis, which has been rejected by mainstream scholarship, developed directly from the Asiatic Race Theory, and argued that the Ethiopid and Arabid populations of the Horn of Africa were the inventors of agriculture and had brought all civilization to Africa. It asserted that these people were Caucasians, not Negroid. It also rejected any Biblical basis despite using Hamitic as the theory's name.[225] Charles Gabriel Seligman in his Some Aspects of the Hamitic Problem in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1913) and later works argued that the ancient Egyptians were among this group of Caucasian Hamites, having arrived in the Nile Valley during early prehistory and introduced technology and agriculture to primitive natives they found there.[226]

The Italian anthropologist Giuseppe Sergi (1901) believed that ancient Egyptians were the Eastern African (Hamitic) branch of the Mediterranean race, which he called "Eurafrican". According to Sergi, the Mediterranean race or "Eurafrican" contains three varieties or sub-races: the African (Hamitic) branch, the Mediterranean "proper" branch and the Nordic (depigmented) branch.[227] Sergi maintained in summary that the Mediterranean race (excluding the depigmented Nordic or 'white') is: "a brown human variety, neither white nor Negroid, but pure in its elements, that is to say not a product of the mixture of Whites with Negroes or Negroid peoples".[228] Grafton Elliot Smith modified the theory in 1911,[229] stating that the ancient Egyptians were a dark haired "brown race",[230] most closely "linked by the closest bonds of racial affinity to the Early Neolithic populations of the North African littoral and South Europe",[231] and not Negroid.[232] Smith's "brown race" is not synonymous or equivalent with Sergi's Mediterranean race.[233] The Hamitic Hypothesis was still popular in the 1960s and late 1970s and was supported notably by Anthony John Arkell and George Peter Murdock.[234]

At the UNESCO "Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script" in Cairo in 1974, none of the participants explicitly voiced support for any theory where Egyptians were Caucasian with a dark pigmentation."[12]:43[23] The current position of modern scholarship is that the Egyptian civilization was an indigenous Nile Valley development (see population history of Egypt).[41][42][43][44]

Turanid race hypothesis

The Turanid race hypothesis, which has been rejected by mainstream scholarship, is the hypothesis that the ancient Egyptians belonged to the Turanid race, linking them to the Tatars.

It was proposed by Egyptologist Samuel Sharpe in 1846, who was "inspired" by some ancient Egyptian paintings, which depict Egyptians with sallow or yellowish skin. He said "From the colour given to the women in their paintings we learn that their skin was yellow, like that of the Mongul Tartars, who have given their name to the Mongolian variety of the human race.... The single lock of hair on the young nobles reminds us also of the Tartars."[235]

The current position of modern scholarship is that the Egyptian civilization was an indigenous Nile Valley development (see population history of Egypt).[41][42][43][44]

Dynastic race theory

The Dynastic race theory, which has been rejected by mainstream scholarship, is the hypothesis that a Mesopotamian force had invaded Egypt in predynastic times, imposed itself on the indigenous Badarian people, and become their rulers.[41][236] It further argued that the Mesopotamian-founded state or states then conquered both Upper and Lower Egypt and founded the First Dynasty of Egypt.

It was proposed in the early 20th century by Egyptologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, who deduced that skeletal remains found at pre-dynastic sites at Naqada (Upper Egypt) indicated the presence of two different races, with one race differentiated physically by a noticeably larger skeletal structure and cranial capacity.[237] Petrie also noted new architectural styles—the distinctly Mesopotamian "niched-facade" architecture—pottery styles, cylinder seals and a few artworks, as well as numerous Predynastic rock and tomb paintings depicting Mesopotamian style boats, symbols, and figures. Based on plentiful cultural evidence, Petrie concluded that the invading ruling elite was responsible for the seemingly sudden rise of Egyptian civilization. In the 1950s, the Dynastic Race Theory was widely accepted by mainstream scholarship.[42][238][239]

While there is clear evidence the Naqada II culture borrowed abundantly from Mesopotamia, the Naqada II period had a large degree of continuity with the Naqada I period,[240] and the changes which did happen during the Naqada periods happened over significant amounts of time.[241] The most commonly held view today is that the achievements of the First Dynasty were the result of a long period of cultural and political development,[242] and the current position of modern scholarship is that the Egyptian civilization was an indigenous Nile Valley development (see population history of Egypt).[41][42][43][243][44]

The Senegalese Egyptologist Cheikh Anta Diop, fought against the Dynastic Race Theory with their own "Black Egyptian" theory and claimed, among other things, that Eurocentric scholars supported the Dynastic Race Theory "to avoid having to admit that Ancient Egyptians were black".[244] Martin Bernal proposed that the Dynastic Race theory was conceived by European scholars to deny Egypt its African roots.[245]

See also

Notes

References

- Edith Sanders: The Hamitic hypothesis: its origin and functions in time perspective, The Journal of African History, Vol. 10, No. 4 (1969), pp. 521–532

- Lefkowitz, Mary R; Rogers, Guy Maclean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. p. 162. ISBN 9780807845554. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- Bard, Kathryn A; Shubert, Steven Blake (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. p. 329. ISBN 9780415185899. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- Stephen Howe (1999). Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. p. 19. ISBN 9781859842287. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- Montellano, Bernard R. Ortiz De (1993). "Melanin, afrocentricity, and pseudoscience". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 36 (S17): 33–58. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330360604. ISSN 1096-8644.

- "Slavery, Genocide and the Politics of Outrage". MERIP. March 6, 2005. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Brace, C. Loring; Tracer, David P.; Yaroch, Lucia Allen; Robb, John; Brandt, Kari; Nelson, A. Russell (2005), "Clines and clusters versus 'Race': a test in ancient Egypt and the case of a death on the Nile", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 36 (S17): 1–31, doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330360603

- "Original Papers: Ancient Egyptians". The New-England Magazine. 0005 (4): 273–280. October 1833.

- Chasseboeuf 1862, p. 131.

- Chasseboeuf 1787, p. 74–77.

- Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African Origin of Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 978-1-55652-072-3.

- Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 1–118. ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7.

- Jacques Joseph 1839, p. 27.

- Milton & Bandia 2009, p. 215.

- Foster, Herbert J. (1974). "The Ethnicity of the Ancient Egyptians". Journal of Black Studies. 5 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1177/002193477400500205. JSTOR 2783936. S2CID 144961394.

- Campbell 1851, p. 10–12.

- Baum 2006, p. 105–108.

- Baum 2006, p. 108.

- Baum 2006, p. 105.

- Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Neues Reich. Theben [Thebes]: Der el Medînet [Dayr al-Madînah Site]: Stuckbild aus Grab 10. [jetzt im K. Museum zu Berlin.], (1849 - 1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- Petrie 1939, p. 155.

- Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- UNESCO, Symposium on the Peopling of Ancient Egypt and the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script; Proceedings, (Paris: 1978), pp. 3–134

- Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. p. 46. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- "American Anthropological Association Statement on Race", American Anthropologist Volume 100. Arlington County: AAA, 1998 (Occasionally re-included in other volumes afterwards.)

- "Biological Aspects of Race" Archived March 12, 2017, at the Wayback Machine American Journal of Physical Anthropology Volume 101. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1996

- Stuart Tyson Smith,(2001) The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Donald Redford, Oxford University Press. p. 27–28

- Bard, in turn citing Bruce Trigger, "Nubian, Black, Nilotic?", in African in Antiquity, The Arts of Nubian and the Sudan, vol 1, 1978.

- Frank M. Snowden Jr., Bernal's 'Blacks' and the Afrocentrists, Black Athena Revisited, p. 122

- Mertz, Barbara (January 25, 2011). Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-208716-4.

- Lefkowitz, Mary R.; Rogers, Guy MacLean (March 24, 2014). Black Athena Revisited. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-2032-9.

- Nielsen, Nicky (August 30, 2020). Egyptomaniacs: How We Became Obsessed with Ancient Epypt. Pen and Sword History. ISBN 978-1-5267-5404-2.

- Specter, Michael (February 26, 1990). "WAS NEFERTITI BLACK? BITTER DEBATE ERUPTS". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review", 1996, in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, Black Athena Revisited, 1996, The University of North Carolina Press, pp. 62–100.

- Kemp, Barry J. (May 7, 2007). Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilisation. Routledge. pp. 46–58. ISBN 9781134563883.

- Keita, S.O.Y. (September 16, 2008). "Ancient Egyptian Origins:Biology". National Geographic. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- Page, Thomas. "DNA discovery unlocks secrets of ancient Egyptians". CNN.

- Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (May 30, 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815694S. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

-

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (May 30, 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815694S. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (May 30, 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815694S. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824. - Schuenemann, Verena; Peltzer, Alexander; Welte, Beatrix (May 30, 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815694S. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

- Early dynastic Egypt, by Toby A. H. Wilkinson, p. 15

- Prehistory and Protohsitory of Egypt, Emile Massoulard, 1949

- Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review" in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, eds. Black Athena Revisited. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. pp. 62–100

- Sonia R. Zakrzewski: Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state – Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton, Highfield, Southampton (2003)

- Keita, Gourdine, Gourdine, Anselin, SOY, Jean-Philippe, Jean-Luc, Alain. "Ancient Egyptian Genomes from northern Egypt: Further Discussion". OSFReprints. pp. 1–8. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

Schuenemann et al. study is best seen as a contribution to understanding a local population history in northern Egypt as opposed to a population history of all Egypt from its inception

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Ancient Egyptians more closely related to Europeans than modern Egyptians, scientists claim". The Independent. May 30, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Manni, Franz; Leonardi, Pascal; Barakat, Abdelhamid; Rouba, Hassan; Heyer, Evelyne; Klintschar, Michael; McElreavey, Ken; Quintana-Murci, Lluis (2002). "Y-Chromosome Analysis in Egypt Suggests a Genetic Regional Continuity in Northeastern Africa". Human Biology. 74 (5): 645–658. doi:10.1353/hub.2002.0054. PMID 12495079. S2CID 26741827.

- Arredi, Barbara; Poloni, Estella S.; Paracchini, Silvia; Zerjal, Tatiana; Fathallah, Dahmani M.; Makrelouf, Mohamed; Pascali, Vincenzo L.; Novelletto, Andrea; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2004). "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in North Africa". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (2): 338–345. doi:10.1086/423147. PMC 1216069. PMID 15202071.

- Kujanová, Martina; Pereira, Luísa; Fernandes, Verónica; Pereira, Joana B.; čErný, Viktor (2009). "Near Eastern Neolithic genetic input in a small oasis of the Egyptian Western Desert". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 140 (2): 336–346. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21078. PMID 19425100.

- Diversity of 17-locus Y-STR haplotypes in Upper (Southern) Egyptians Ghada A. Omran, Guy N. Rutty, Mark A. Jobling, 2007, Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series 1 (2008) 230–232, at

- Cruciani, Fulvio; Santolamazza, Piero; Shen, Peidong; MacAulay, Vincent; Moral, Pedro; Olckers, Antonel; Modiano, David; Holmes, Susan; Destro-Bisol, Giovanni; Coia, Valentina; Wallace, Douglas C.; Oefner, Peter J.; Torroni, Antonio; Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca; Scozzari, Rosaria; Underhill, Peter A. (2002). "A Back Migration from Asia to Sub-Saharan Africa is Supported by High-Resolution Analysis of Human Y-Chromosome Haplotypes". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (5): 1197–1214. doi:10.1086/340257. PMC 447595. PMID 11910562.

- Lucotte, G.; Mercier, G. (2003). "Brief communication: Y-chromosome haplotypes in Egypt". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (1): 63–66. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10190. PMID 12687584.

- Cabrera, Vicente M.; Marrero, Patricia; Abu-Amero, Khaled K.; Larruga, Jose M. (2018). "Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basal lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 18 (1): 98. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1211-4. PMC 6009813. PMID 29921229.

- Luis, J.R.; Rowold, D.J.; Regueiro, M.; Caeiro, B.; Cinnioğlu, C.; Roseman, C.; Underhill, P.A.; Cavalli-Sforza, L.L.; Herrera, R.J. (2004). "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (3): 532–544. doi:10.1086/382286. PMC 1182266. PMID 14973781.

- Hervella, M.; Svensson, E. M.; Alberdi, A.; Günther, T.; Izagirre, N.; Munters, A. R.; Alonso, S.; Ioana, M.; Ridiche, F.; Soficaru, A.; Jakobsson, M.; Netea, M. G.; De-La-Rua, C. (2016). "The mitogenome of a 35,000-year-old Homo sapiens from Europe supports a Palaeolithic back-migration to Africa". Scientific Reports. 6: 25501. Bibcode:2016NatSR...625501H. doi:10.1038/srep25501. PMC 4872530. PMID 27195518.

- Secher, Bernard; Fregel, Rosa; Larruga, José M.; Cabrera, Vicente M.; Endicott, Phillip; Pestano, José J.; González, Ana M. (2014). "The history of the North African mitochondrial DNA haplogroup U6 gene flow into the African, Eurasian and American continents". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14: 109. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-109. PMC 4062890. PMID 24885141. S2CID 14612793.

- Henn, Brenna M.; Botigué, Laura R.; Gravel, Simon; Wang, Wei; Brisbin, Abra; Byrnes, Jake K.; Fadhlaoui-Zid, Karima; Zalloua, Pierre A.; Moreno-Estrada, Andres; Bertranpetit, Jaume; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Comas, David (2012). "Genomic Ancestry of North Africans Supports Back-to-Africa Migrations". PLOS Genetics. 8 (1): e1002397. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002397. PMC 3257290. PMID 22253600.

- Olivieri, A.; Achilli, A.; Pala, M.; Battaglia, V.; Fornarino, S.; Al-Zahery, N.; Scozzari, R.; Cruciani, F.; Behar, D. M.; Dugoujon, J.-M.; Coudray, C.; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. S.; Semino, O.; Bandelt, H.-J.; Torroni, A. (2006). "The mtDNA Legacy of the Levantine Early Upper Palaeolithic in Africa". Science. 314 (5806): 1767–1770. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1767O. doi:10.1126/science.1135566. PMID 17170302. S2CID 3810151.

- González, Ana M.; Larruga, José M.; Abu-Amero, Khaled K.; Shi, Yufei; Pestano, José; Cabrera, Vicente M. (2007). "Mitochondrial lineage M1 traces an early human backflow to Africa". BMC Genomics. 8: 223. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-223. PMC 1945034. PMID 17620140.

- Non, Amy. "ANALYSES OF GENETIC DATA WITHIN AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FRAMEWORK TO INVESTIGATE RECENT HUMAN EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY AND COMPLEX DISEASE" (PDF). University of Florida. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Kivisild, T; Rootsi, S; Metspalu, M; Mastana, S; Kaldma, K; Parik, J; Metspalu, E; Adojaan, M; et al. (2003). "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (2): 313–32. doi:10.1086/346068. PMC 379225. PMID 12536373.

- Quintana; et al. (1999). "Genetic evidence of an early exit of Homo sapiens sapiens from Africa through eastern Africa" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pennarun, E (2012). "Divorcing the Late Upper Paleolithic demographic histories of mtDNA haplogroups M1 and U6 in Africa". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 12:234: 234. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-234. PMC 3582464. PMID 23206491. S2CID 1527904. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- Ancient Egypt: anatomy of a civilization, by Barry J. Kemp, pg 47, view at

- Williams, Chancellor (1987). The Destruction of Black Civilization. Chicago, Illinois: Third World Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-88378-030-5.

- "A New Look at King Tut". The Washington Post. May 11, 2005. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- Eskandary, Hossein; Nematollahi-Mahani, Seyed Noureddin; Zangiabadi, Nasser (January 5, 2012). "Skull Indices in a Population Collected From Computed Tomographic Scans of Patients with Head Trauma". Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 20 (2): 545–550. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e31819b9f6e. PMID 19305252. S2CID 206050171. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- "Discovery.com". Archived from the original on February 20, 2009.

- "Science museum images". Sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- "King Tut's New Face: Behind the Forensic Reconstruction". News.nationalgeographic.com. October 28, 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- Henerson, Evan (June 15, 2005). "King Tut's skin colour a topic of controversy". U-Daily News — L.A. Life. Archived from the original on October 30, 2006. Retrieved August 5, 2006.

- "Tutankhamun was not black: Egypt antiquities chief". AFP. September 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- "Welcome to Ancient Egypt Magazine's Web Site". Ancientegyptmagazine.com\Accessdate=2016-06-02.

- "Photographic image : Wikimedia Commons" (JPG). Commons.wikimedia.org. December 10, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- "Tutankhamun: beneath the mask". Sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- "King Tut Related to Half of European Men? Maybe Not". Live Science. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- Hugh B. Price, "Was Cleopatra Black?". The Baltimore Sun. September 26, 1991. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- Roller (2010).

- Charles Whitaker, "Was Cleopatra Black?". Ebony. February 2002. Retrieved May 28, 2012. The author cites a few examples of the claim, one of which is a chapter titled "Black Warrior Queens", published in 1984 in Black Women in Antiquity, part of The Journal of African Civilization series. It draws heavily on the work of J.A. Rogers.

- Mona Charen, "Afrocentric View Distorts History and Achievement by Blacks". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 14, 1994. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- Lefkowitz (1992), pp. 36–40.

- World's Great Men of Color, Volume I, By J.A. Rogers; Simon and Schuster, 2011; ISBN 9781451650549

- Lefkowitz (1992), pp. 40–41.

- Roller, Duane W. (2010), Cleopatra: a biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 54, 174–175, ISBN 978-0-19-536553-5.

- Samson (1990), p. 104.

- Schiff (2011), p. 35-36.

- Preston (2009), p. 77.

- Goldsworthy (2010), pp. 8, 127–128.

- Schiff (2011), pp. 2, 42.

- Grant (2009), p. 4.

- Preston (2009), p. 22.

- Jones (2006), pp. xiii.

- Schiff (2011), p. 28.

- Kleiner (2005), p. 22.

- Tyldesley, pp. 30, 235–236.

- Grant (1972), p. 5.

- Roller (2010), pp. 15, 18, 166.

- Schiff (2011), pp. 2, 41–42.

- Pina Polo (2013), pp. 185–186.

- Kleiner (2005), pp. 151–153, 155.

- Bradford (2003), pp. 14, 17.

- Foggo, Daniel (March 15, 2009). "Found the sister Cleopatra killed". The Times. London. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- "Also in the news | Cleopatra's mother 'was African'". BBC News. March 16, 2009. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- The Lives of Cleopatra and Octavia, By Sarah Fielding, Christopher D. Johnson, p. 154, Bucknell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8387-5257-9

- "Phrenology and "Scientific Racism" in the 19th Century". Vassar College Word Press. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "Have Bones of Cleopatra's Murdered Sister Been Found?". Live Science. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- "The skeleton of Cleopatra's sister? Steady on". The Times Literary Supplement. March 15, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- "Uncovering Secrets of the Sphinx". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- Curran, Brian A. (January 1, 1998). "The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili and Renaissance Egyptology". Word & Image. 14 (1–2): 156–185. doi:10.1080/02666286.1998.10443948. ISSN 0266-6286.

- Volney, C-F (1807). Voyage en Syrie et en Égypte : pendant les années 1783, 1784 et 1785 …. Paris: Paris : Chez Courcier, imprimeur-libraire. p. 71.

When I visited the sphinx ... on seeing that head, typically Negro in all its features, I remembered ... Herodotus says: ... the Egyptians ... are black with woolly hair....

- "... its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro's ... the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect ... the lips are thick...." Flaubert, Gustave. Flaubert in Egypt, ed. Francis Steegmuller. (London: Penguin Classics, 1996). ISBN 978-0-14-043582-5.

- Denon, Vivant (1803). Travels in Upper and Lower Egypt. General Bonaparte. pp. 269–270.

the character is African, but the mouth, the lips of which are thick

- Graham W. Irwin (January 1, 1977). Africans abroad: a documentary history of the Black Diaspora in Asia, Latin …. ISBN 9780231039369. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- W. E. B. Du Bois (April 24, 2001). The Negro. ISBN 978-0812217759. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Black man of the Nile and his family, by Yosef Ben-Jochannan, pp. 109–110

- Diop 1974, p. Frontispiece,27,43,51-53.

- Asante, Molefi Kete (1996). European Racism Regarding Ancient Egypt: Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-936260-64-8.

- Schoch, Robert M. (1995). "Great Sphinx Controversy". robertschoch.net. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- "Fortean Times" (79). London. February 1995. pp. 34, 39.

- Fritze, Ronald H. (2009). Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-Religions. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-430-4

- "Scholars Dispute Claim That Sphinx Is Much Older". The New York Times, 09 February 1992.

- Card, Jeb J.; Anderson, David S. (September 15, 2016). Lost City, Found Pyramid: Understanding Alternative Archaeologies and Pseudoscientific Practices. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1911-3.

- Diehl 2004, p.112. Cyphers 1996, p. 156.

- Diop 1974, pp. 246-248.

- Levine, Molly Myerowitz (2004). "David M. Goldenberg, The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity, and Islam". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- Shavit 2001: 148

- Aboubacry Moussa Lam, "L'Égypte ancienne et l'Afrique", in Maria R. Turano et Paul Vandepitte, Pour une histoire de l'Afrique, 2003, pp. 50 &51

- Kemp 2006, p. 21.

- Raymond Faulkner, A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2002, p. 286.

- Gardiner, Alan (1957) [1927]. Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs (3 ed.). Griffith Institute, Oxford. ISBN 978-0-900416-35-4.

- Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. p. 10. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Charlotte Booth, The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies (2007) p. 217

- "Nubia Gallery". The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Emberling, Geoff (2011). Nubia: Ancient Kingdoms of Africa. New York, NY: The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. pp. 22–23, 36–37. ISBN 978-0-615-48102-9.

- Snowden, Frank (1970). Blacks in Antiquity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 3.

- Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, Vol. 2. by Simson Najovits p. 318

- Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Dynastie IV. Pyramiden von Giseh [Jîzah], Grab 24. [ Grabkammer No. 2 im K. Museum zu Berlin.], (1849 - 1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- "Ra-Hotep and Nofret: Modern Forgeries in the Cairo Museum?" pp. 207–212 in Egypt: Child of Africa (1994), edited by Ivan Van Sertima.

- "AFRICANA STUDIES". Manuampim.com. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- "The Book of Gates: The Book of Gates: Chapter VI. The Gate Of Teka-Hra. The Fifth Division of the Tuat". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(still image) Neues Reich. Dynastie XIX. Theben [Thebes]. Bab el Meluk [Bîbân el-Mulûk]. Grab Sethos I. [Plan No. XVII] a. d. Raum D. [Forsetzung von Bl. 135]; c. Pfeiler aus Raum J; d. Ecke aus Raum M. [c. und d. jetzt im K. Mus. zu Berlin], (1849 - 1856)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "Africana Studies. Tomb of Rameses III". Manuampim.com. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- Frank Yurco, "Two Tomb-Wall Painted Reliefs of Ramesses III and Sety I and Ancient Nile Valley Population Diversity", in Egypt in Africa (1996), ed. by Theodore Celenko.

- Bagnall, R.S. (2000). Susan Walker (ed.). Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits in Roman Egypt. Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications. New York: Routledge. p. 27.

- Irish, JD (April 2006). "Who were the ancient Egyptians? Dental affinities among Neolithic through postdynastic peoples". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 129 (4): 529–543. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20261. PMID 16331657.

- Davidson, Basil (1991). African Civilization Revisited: From Antiquity to Modern Times. Africa World Press.

- Shavit, Yaacov (November 12, 2013). History in Black: African-Americans in Search of an Ancient Past. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-79184-3.

- Graciela Gestoso Singer, "Ahmose-Nefertari, The Woman in Black". Terrae Antiqvae, January 17, 2011

- Gitton, Michel (1973). "Ahmose Nefertari, sa vie et son culte posthume". École Pratique des Hautes études, 5e Section, Sciences Religieuses. 85 (82): 84. doi:10.3406/ephe.1973.20828. ISSN 0183-7451.

- Gardiner, Alan H. (1961). Egypt of the Pharaohs: an introduction. Oxford: Oxford University press., p.175

- https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/former-queen-ahmose-nefertari-protectress-royal-tomb-workers-deified

- Petrie, Flinders (1939). The making of Egypt. London. p.155

- Martin Bernal (1987), Black Athena: Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. The Fabrication of Ancient Greece, 1785-1985, vol. I. New Jersey, Rutgers University Press

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2006. ISBN 0-500-05145-3

- Hodel-Hoenes, S & Warburton, D (trans), Life and Death in Ancient Egypt: Scenes from Private Tombs in New Kingdom Thebes, Cornell University Press, 2000, p. 268.

- Hansberry, William Leo (November 1964). "Africa's Golden Past". Ebony Magazine. Ebony Magazine. p. 32. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- Barringer, Felicity (February 5, 1990). "Ideas & Trends; Africa's Claim to Egypt's History Grows More Insistent". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- Specter, Michael (February 26, 1990). "Was Nefertiti Black? Bitter Debate Erupts". The Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

Queen Tiye, who also lived in the 14th century B.C., was much more clearly a black African.

- Lefkowitz, Mary R; Rogers, Guy Maclean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. p. 162. ISBN 9780807845554. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Bard, Kathryn A; Shubert, Steven Blake (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. p. 329. ISBN 9780415185899. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Stephen Howe (1999). Afrocentrism: Mythical Pasts and Imagined Homes. p. 136. ISBN 9781859842287. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Bernal, Martin (1987). Black Athena. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-8135-1276-1.

- Muḥammad Jamāl al-Dīn Mukhtār (1990). Ancient Civilizations of Africa. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780852550922. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- "Tutankhamun was not black: Egypt antiquities chief". AFP. September 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- Graham W. Irwin (January 1, 1977). Africans abroad: a documentary history of the Black Diaspora in Asia, Latin …. ISBN 9780231039369. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Schoch, Robert M. (1995). "Great Sphinx Controversy". robertschoch.net. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- "Race in Antiquity: Truly Out of Africa | Dr. Molefi Kete Asante". Asante.net. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Hugh B. Price, "Was Cleopatra Black?". The Baltimore Sun. September 26, 1991. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- Charles Whitaker, "Was Cleopatra Black?". Ebony. February 2002. Retrieved May 28, 2012. The author cites a few examples of the claim, one of which is a chapter titled "Black Warrior Queens", published in 1984 in Black Women in Antiquity, part of The Journal of African Civilization series. It draws heavily on the work of J.A. Rogers.

- Mona Charen, "Afrocentric View Distorts History and Achievement by Blacks". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. February 14, 1994. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- Najovits, Simson (2003). Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, Vol. II: A Modern Survey of and Ancient Land. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-256-9.

- Mokhtar, G. (1990). General History of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 1–118. ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7.

- Najovits, Simson (2003). Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, Vol. II: A Modern Survey of and Ancient Land. Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-256-9.

- Alan B. Lloyd (1993). Herodotus. p. 22. ISBN 978-9004077379. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Herodotus (2003). The Histories. London, England: Penguin Books. pp. 103, 119, 134–135, 640. ISBN 978-0-14-044908-2.

- Rawlinson, George (2018). The Histories of Herodotus. Scribe Publishing. ISBN 978-1787801714.

black-skinned and have woolly hair

- Lefkowitz, Mary R; Rogers, Guy Maclean (1996). Black Athena Revisited. p. 118. ISBN 9780807845554. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Diop, Cheikh Anta (1981). Civilization or Barbarism. Chicago, Illinois: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 978-1-55652-048-8.

- Welsby, Derek (1996). The Kingdom of Kush. London: British Museum Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7141-0986-2.

- Heeren, A.H.L. (1838). Historical researches into the politics, intercourse, and trade of the Carthaginians, Ethiopians, and Egyptians. Michigan: University of Michigan Library. pp. 13, 379, 422–424. ASIN B003B3P1Y8.

- Aubin, Henry (2002). The Rescue of Jerusalem. New York, NY: Soho Press. pp. 94–96, 100–102, 118–121, 141–144, 328, 336. ISBN 978-1-56947-275-0.

- Hansberry, William Leo (1977). African & Africans, African History Notebook, Vol. II. Maryland, USA: Black Classic Press. pp. 103–113. ISBN 9781574781540.

- von Martels, Z. R. W. M. (1994). Travel Fact and Travel Fiction: Studies on Fiction, Literary Tradition …. p. 1. ISBN 978-9004101128. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Kenton L. Sparks (1998). Ethnicity and Identity in Ancient Israel: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnic …. p. 59. ISBN 9781575060330. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- David Asheri; Alan Lloyd; Aldo Corcella (August 30, 2007). A Commentary on Herodotus. p. 74. ISBN 9780198149569. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Jennifer T. Roberts (June 23, 2011). Herodotus: A Very Short Introduction. p. 115. ISBN 9780199575992. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Alan Cameron (September 2, 2004). Greek Mythography in the Roman World. p. 156. ISBN 9780198038214. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- John Marincola (December 13, 2001). Greek Historians. p. 34. ISBN 9780199225019. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Amoia, Professor Emeritus Alba; Amoia, Alba Della Fazia; Knapp, Bettina Liebowitz; Knapp, Bettina Liebowitz Knapp (2002). Multicultural Writers from Antiquity to 1945: A Bio-bibliographical Sourcebook. p. 171. ISBN 9780313306877. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- David G. Farley (November 30, 2010). Modernist Travel Writing: Intellectuals Abroad. p. 21. ISBN 9780826272287. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Alan B. Lloyd (1993). Herodotus. p. 1. ISBN 978-9004077379. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Flemming A. J. Nielsen (November 1, 1997). The Tragedy in History: Herodotus and the Deuteronomistic History. p. 41. ISBN 9781850756880. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Herodotus: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide - Oxford University Press. Oxford University Press. May 1, 2010. p. 21. ISBN 9780199802869. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Alain Ricard, Naomi Morgan, The Languages & Literatures of Africa: The Sands of Babel, James Currey, 2004, p. 14

- Snowden, Frank (1983). Before Color Prejudice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-674-06380-8.

- DeMello. Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. p. 150.

The ancient Egyptians practiced head binding as early as 3000 BCE,... the Mangbetu of the Congo also practiced head binding.

- Williams, Bruce (2011). Before the Pyramids. Chicago, Illinois: Oriental Institute Museum Publications. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-885923-82-0.

- "The Nubia Salvage Project | The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago". Oi.uchicago.edu. Retrieved June 2, 2016.