Egypt–Mesopotamia relations

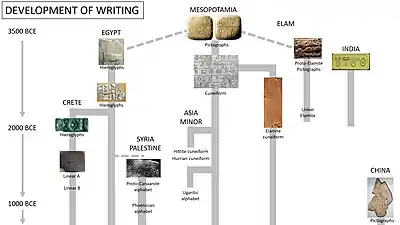

Egypt–Mesopotamia relations were the relations between the civilisations of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, in the Middle East. They seem to have developed from the 4th millennium BCE, starting in the Uruk period for Mesopotamia and the Gerzean culture of Prehistoric Egypt (circa 3500–3200 BCE).[3][4] Influences can be seen in the visual arts of Egypt, in imported products, and also in the possible transfer of writing from Mesopotamia to Egypt[4] and generated "deep-seated" parallels in the early stages of both cultures.[2]

Influences on Egyptian trade and art (3500–3200 BCE)

(3400–3200 BCE)

There was generally a high-level of trade between Ancient Egypt and the Near East throughout the Pre-dynastic period of Egypt, during the Naqada II (3600–3350 BCE) and Naqada III (3350–2950 BCE) phases.[7] These were contemporary with the Late Uruk (3500–3100 BCE) and Jemdet Nasr (3100–2900 BCE) periods in Mesopotamia.[7] The main period of cultural exchange, particularly consisting in the transfer of Mesopotamian imagery and symbols to Egypt, is considered to have lasted about 250 years, during the Naqada II to Dynasty I periods.[8]

Designs and objects

Distinctly foreign objects and art forms entered Egypt during this period, indicating contacts with several parts of Asia. The designs that were emulated by Egyptian artists are numerous: the Uruk "priest-king" with his tunic and brimmed hat in the posture of the Master of animals, the serpopards , winged griffins, snakes around rosettes, boats with high prows, all characteristic of Mesopotamian art of the Late Uruk (Uruk IV, c. 3350–3200 BCE) period.[9][10] The same "Priest-King" is visible in several Mesopotamian works of art of the end of the Uruk period, such as the Blau Monuments, cylinder seals and statues.[11] Objects such as the Gebel el-Arak knife handle, which has patently Mesopotamian relief carvings on it, have been found in Egypt,[3] and the silver which appears in this period can only have been obtained from Asia Minor.[12]

Mesopotamian-style pottery in Egypt (3500 BCE)

Red-slipped spouted pottery items dating to around 3500 BCE (Naqada II C/D), which were probably used for pouring water, beer or wine, suggest that Egypt was in contact with Mesopotamia around that time.[13] This type of pottery was manufactured in Egypt, with Egyptian clay, but its shape, particularly the spout, is Mesopotamian in origin.[13] Such vessels were novel in pre-Dynastic Egypt, but were commonly manufactured in the cities of Nippur and Uruk.[13] This indicated that Egyptians were familiar with Mesopotamian types of pottery.[13] The discovery of these vessels initially encouraged the development of the dynastic race theory, according to which Mesopotamians would have established the first Pharaonic line, but is now considered to be simply indicative of cultural contacts and borrowings circa 3500 BCE.[13]

Spouted jars of Mesopotamian design start to appear in Egypt in the Naqada II period.[7] Various Uruk pottery vases and containers have been found in Egypt in Naqada contexts, confirming that Mesopotamian finished goods were imported into Egypt, although the past contents of the jars have not been determined yet.[14] Scientific analysis of ancient wine jars in Abydos has shown there was some high-volume wine trade with the Levant during this period.[15]

Adoption of Mesopotamian-style maceheads

Egyptians used traditional disk-shaped maceheads during the early phase of Naqada culture, circa 4000–3400 BCE. At the end of the period, the disk-shaped macehead was replaced by the superior Mesopotamian-style pear-shaped macehead as seen on the Narmer Palette.[16] The Mesopotamian macehead was much heavier with a wider impact surface, and was capable of giving much more damaging blows than the original Egyptian disk-shaped macehead.[16]

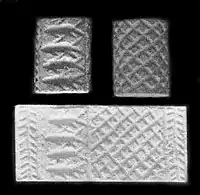

Cylinder seals

It is generally thought that cylinder seals were introduced from Mesopotamia to Egypt during the Naqada II period.[18] Cylinder seals, some coming from Mesopotamia and Elam, and some made locally in Egypt following Mesopotamian designs in a stylized manner, have been discovered in the tombs of Upper Egypt dating to Naqada II and III, particularly in Hierakonpolis.[7][8] Mesopotamian cylinder seals have been found in the Gerzean context of Naqada II, in Naqada and Hiw, attesting to the expansion of the Jemdet Nasr culture as far as Egypt at the end of the 4th millennium BCE.[19][20]

In Egypt, cylinder seals suddenly appear without local antecedents from around Naqada II c-d (3500–3300 BCE).[21] The designs are similar to those of Mesopotamia, where they were invented during the early 4th millennium BCE, during the Uruk period, as an evolutionary step from various accounting systems and seals going back as early as the 7th millennium BCE.[21] The earliest Egyptian cylinder seals are clearly similar to contemporary Uruk seals down to Naqada II-d (circa 3300 BCE), and may even have been manufactured by Mesopotamian craftsmen, but they start to diverge from circa 3300 BCE to become more Egyptian in character.[21]

Cylinder seals were made in Egypt as late as the Second Intermediate Period, but they were essentially replaced by scarabs from the time of the Middle Kingdom.[18]

Other objects and designs

Lapis Lazuli was imported in great quantity by Egypt, and already used in many tombs of the Naqada II period. Lapis Lazuli probably originated in northern Afghanistan, as no other sources are known, and had to be transported across the Iranian plateau to Mesapotamia, and then Egypt.[22][14]

In addition, Egyptian objects were created which clearly mimic Mesopotamian forms, although not slavishly.[23] Cylinder seals appear in Egypt, as well as recessed paneling architecture, the Egyptian reliefs on cosmetic palettes are clearly made in the same style as the contemporary Mesopotamian Uruk culture, and the ceremonial mace heads which turn up from the late Gerzean and early Semainean are crafted in the Mesopotamian "pear-shaped" style, instead of the Egyptian native style.[24] The first man/animal composite creatures in Egypt were directly copied from Mesopotamian designs.[25] It is also considered as certain that the Egyptians adopted from Mesopotamia the practice of marking the sealing of jars with engraved cylinder seals for informational purposes.[26]

Temples and pyramids

Egyptian architecture also was influenced, as it adopted element of Mesopotamian Temple and civic architecture.[28]

Recessed niches in particular, which are characteristic of Mesopotamian Temple architecture, were adopted for the design of false doors in the tombs of the First Dynasty and Second Dynasty, from the time of the Naqada III period (circa 3000 BCE).[28][29] It is unknown if the transfer of this design was the result of Mesopotamian workmen in Egypt, or if temple designs on imported Mesopotamian seals may have been a sufficient source of inspiration for Egyptian architects.[28]

The design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the Egyptian pyramids, the earliest of which dates to circa 2600 BCE.

Transmission

The route of this trade is difficult to determine, but contact with Canaan does not predate the early dynastic, so it is usually assumed to have been by sea trade.[1] During the time when the Dynastic Race Theory was still popular, it was theorized that Uruk sailors circumnavigated Arabia, but a Mediterranean route, probably by middlemen through Byblos, is more likely, as evidenced by the presence of Byblian objects in Egypt.[1] Glyptic art also seems to have played a key role, through the circulation of decorated cylinder seals across the Levant, a common hinterland of both empire.[32]

The intensity of the exchanges suggest however that the contacts between Egypt and Mesopotamia were often direct, rather than merely through middlemen or through trade.[2] Uruk had known colonial outposts of as far as Habuba Kabira, in modern Syria, insuring their presence in the Levant.[33] Numerous Uruk cylinder seals have also been uncovered there.[33] There were suggestions that Uruk may have had an outpost and a form of colonial presence in northern Egypt.[33] The site of Buto in particular was suggested, but it has been rejected as a possible candidate.[28]

The fact that so many Gerzean sites are at the mouths of wadis which lead to the Red Sea may indicate some amount of trade via the Red Sea (though Byblian trade potentially could have crossed the Sinai and then be taken to the Red Sea).[34] Also, it is considered unlikely that something as complicated as recessed panel architecture could have worked its way into Egypt by proxy, and at least a small contingent of migrants is often suspected.[1]

These early contacts probably acted as a sort of catalyst for the development of Egyptian culture, particularly in respect to the inception of writing, and the codification of royal and vernacular imagery.[2]

Egyptian palettes, such as the Narmer Palette (3200–3000 BC), borrow elements of Mesopotamian iconography, in particular the sauropod design of Uruk.[35]

Egyptian palettes, such as the Narmer Palette (3200–3000 BC), borrow elements of Mesopotamian iconography, in particular the sauropod design of Uruk.[35] Beads of Lapis Lazuli and travertine, circa 3650 –3100 BCE. Naqada II–Naqada III.

Beads of Lapis Lazuli and travertine, circa 3650 –3100 BCE. Naqada II–Naqada III..jpg.webp) Egyptian statuette, 3300–3000 BC. The Lapis lazuli material is thought to have been imported through Mesopotamia from Afghanistan. Ashmolean.[22][14]

Egyptian statuette, 3300–3000 BC. The Lapis lazuli material is thought to have been imported through Mesopotamia from Afghanistan. Ashmolean.[22][14] Egyptian necklace and pendant, using lapis lazuri imported from Afghanistan, possibly by Mesopotamian traders, Naqada II circa 3500 BCE, British Museum EA57765 EA57586.[36][37][38]

Egyptian necklace and pendant, using lapis lazuri imported from Afghanistan, possibly by Mesopotamian traders, Naqada II circa 3500 BCE, British Museum EA57765 EA57586.[36][37][38]

Importance of local Egyptian developments

While there is clear evidence the Naqada II culture borrowed abundantly from Mesopotamia, the most commonly held view today is that the achievements of the First Dynasty were the result of a long period of indigenous cultural and political development.[40] Such developments are much older than the Naqada II period,[41] the Naqada II period had a large degree of continuity with the Naqada I period,[42] and the changes which did happen during the Naqada periods happened over significant amounts of time.[43]

Although there are many examples of Mesopotamian influence in Egypt in the 4th millennium BCE, the reverse is not true, and there are no traces of Egyptian influence in Mesopotamia at that time.[44] Only very few Egyptian Naqada period object have been found beyond Egypt, and generally in its vicinity, such as a rare Naqada III Egyptian Cosmetic palette in the shape of a fish, of the end of 4th millennium BCE, found in Ashkelon or Gaza.[45]

Development of writing (3500–3200 BCE)

It is generally thought that Egyptian hieroglyphs "came into existence a little after Sumerian script, and, probably [were], invented under the influence of the latter",[49] and that it is "probable that the general idea of expressing words of a language in writing was brought to Egypt from Sumerian Mesopotamia".[50][51] The two writing systems are in fact quite similar in their initial stages, relying heavily on pictographic forms and then evolving a parallel system for the expression of phonetic sounds.[2]

Standard reconstructions of the development of writing generally place the development of the Sumerian proto-cuneiform script before the development of Egyptian hieroglyphs, with the suggestion the former influenced the latter.[46]

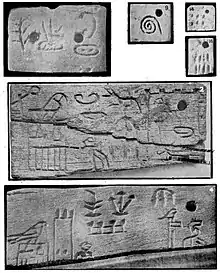

There is however a lack of direct evidence, and "no definitive determination has been made as to the origin of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt".[52] Instead, it is pointed out and held that "the evidence for such direct influence remains flimsy” and that “a very credible argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt..."[53] Since the 1990s, the discovery of glyphs on clay tags at Abydos, dated to between 3400 and 3200 BCE, may challenge the classical notion according to which the Mesopotamian symbol system predates the Egyptian one, although Egyptian writing does make a sudden apparition at that time, while on the contrary Mesopotamia has an evolutionary history of sign usage in tokens dating back to circa 8000 BCE.[54][15] Also, the Abydos clay tags are virtually identical with contemporary clay tags from Uruk, Mesopotamia.[55]

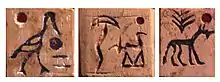

Tablet with Mesopotamian proto-cuneiform pictographic characters (end of 4th millennium BC), Uruk III.

Tablet with Mesopotamian proto-cuneiform pictographic characters (end of 4th millennium BC), Uruk III. Mesopotamian pierced label, with symbol "EN" meaning "Master", the reverse of the plaque has the symbol for Goddess Inanna. Uruk circa 3000 BC. Louvre Museum AO 7702

Mesopotamian pierced label, with symbol "EN" meaning "Master", the reverse of the plaque has the symbol for Goddess Inanna. Uruk circa 3000 BC. Louvre Museum AO 7702

Labels with some of the earliest Egyptian hieroglyphs from the tomb of Egyptian king Menes (3200–3000 BC)

Labels with some of the earliest Egyptian hieroglyphs from the tomb of Egyptian king Menes (3200–3000 BC).jpg.webp) Ivory plaque of Menes (3200–3000 BC)

Ivory plaque of Menes (3200–3000 BC)

Near Eastern genetic affinity of ancient Egyptian mummies

A 2017 study of the mitochondrial DNA composition of Egyptian mummies has shown a high level of affinity with the DNA of the populations of the Near East.[57][58] The study was made on mummies of Abusir el-Meleq, near El Fayum, which was inhabited from at least 3250 BCE until about 700 CE.[59] A shared drift and mixture analysis of the DNA of these ancient Egyptian mummies shows that the connection is strongest with ancient populations from the Levant, the Near East and Anatolia, and to a lesser extent modern populations from the Near East and the Levant.[58] In particular the study finds "that ancient Egyptians are most closely related to Neolithic and Bronze Age samples in the Levant, as well as to Neolithic Anatolian and European populations".[59]

Overall the mummies studied were closer genetically to Near Eastern people than the modern Egyptian population, which has a greater proportion of genes coming from sub-Saharan Africa after the Roman period.[57][58]

The data suggest a high level of genetic interaction with the Near East since ancient times, probably going back to Prehistoric Egypt: "Our data seem to indicate close admixture and affinity at a much earlier date, which is unsurprising given the long and complex connections between Egypt and the Middle East. These connections date back to Prehistory and occurred at a variety of scales, including overland and maritime commerce, diplomacy, immigration, invasion and deportation".[60][58]

The study stated that "our genetic time transect suggests genetic continuity between the Pre-Ptolemaic, Ptolemaic and Roman populations of Abusir el-Meleq, indicating that foreign rule impacted the [the native] population only to a very limited degree at the genetic level."

Egyptian influence on Mesopotamian art

After this early period of exchange, and the direct introduction of Mesopotamia components in Egyptian culture, Egypt soon started to assert its own style from the Early Dynastic Period (3150–2686 BCE), the Narmer palette being seen as a turning point.[62]

Egypt seems to have provided some artistic feedback to Mesopotamia at the time of the Early Dynastic Period of Mesopotamia (2900–2334 BCE).[61] This is especially the case with royal iconography: the figure of the king smiting his enemies with a mace, and the depiction of dead enemies being eaten by birds of prey appeared in Egypt from the time of the Narmer palette, and were then adopted centuries later by Mesopotamian rulers Eannatum and Sargon of Akkad.[61] This depiction appear to be part of an artistic system to promote "hegemonistic kingship".[61] Another example is the usage of decorated mace heads as a symbol of kingship.[61]

There is also a possibility that the depictions of the Mesopotamian king with a muscular, naked, upper body fighting his enemies in a quadrangular posture, as seen in the Stele of Naram-Sin or statues of Gudea (all circa 2000 BCE) were derived from Egyptian sculpture, which by that time had already been through its Golden Age during the Old Kingdom.[63]

Later periods

Trade of Indus goods through Mesopotamia

Etched carnelian beads

Rare etched carnelian bead have been found in Egypt, which thought to have been imported from the Indus Valley Civilization through Mesopotamia. This is related the flourishing of the Indus Valley Civilization, and the development of Indus-Mesopotamia relations from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. Examples of etched carnelian beads found in Egypt typically date to the Late Middle Kingdom (c.1800 BCE). They were found in tombs and represented luxury items, often as the centerpiece of jewelry.[64][65]

Hyksos period

Egypt records various exchanges with West Asian foreigners from around 1900 BCE, as in the paintings of the tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan.

From circa 1650 BCE, the Hyksos, foreigners of probable Levantine origin, established the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt (1650–1550 BCE) based at the city of Avaris in the Nile delta, from where they ruled the northern part of the country.[69][70] Khyan, one of the Hyksos rulers, is known for his wide-ranging contacts, as objects in his name have been found at Knossos and Hattusha indicating diplomatic contacts with Crete and the Hittites, and a sphinx with his name was bought on the art market at Baghdad and might demonstrate diplomatic contacts with Babylon, possibly with the first Kassites ruler Gandash.[71][72][73]

Exchanges would again flourish between the two cultures from the period of the New Kingdom of Egypt (c.1550 BC–c.1069 BC), this time an exchange between two mature and well-established civilizations.[74]

Neo-Assyrian period

In the last phase of historic exchanges, the Neo-Assyrians led the Assyrian conquest of Egypt from 677 to 663 BCE. Various artifacts depicting Egyptian pharaohs, deities or persons have been found in Nimrud, and dated to the Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE.

Carved ivory panel showing young Egyptian pharaohs flanking a lotus stem and flowers. From Nimrud, Iraq. Iraq Museum, Baghdad.

Carved ivory panel showing young Egyptian pharaohs flanking a lotus stem and flowers. From Nimrud, Iraq. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. Carved ivory panel showing young Egyptian men flanking lotus stem and flowers. From Nimrud, Iraq. Iraq Museum.

Carved ivory panel showing young Egyptian men flanking lotus stem and flowers. From Nimrud, Iraq. Iraq Museum. Carved ivory panel showing young bearded Egyptian men flanking lotus stem and flowers. From Nimrud, Iraq. Iraq Museum.

Carved ivory panel showing young bearded Egyptian men flanking lotus stem and flowers. From Nimrud, Iraq. Iraq Museum.

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire again invaded Egypt and established satrapies, founding the Achaemenid Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt (525–404 BCE) and Thirty-first Dynasty of Egypt (343–332 BCE).

.JPG.webp) Egyptian statue of Darius I

Egyptian statue of Darius I.jpg.webp) Darius as Pharaoh of Egypt at the Temple of Hibis

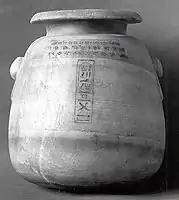

Darius as Pharaoh of Egypt at the Temple of Hibis Jar of Xerxes I, with his name in hieroglyphs and cuneiform

Jar of Xerxes I, with his name in hieroglyphs and cuneiform

See also

References

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 22.

- Hartwig, Melinda K. (2014). A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. John Wiley & Sons. p. 427. ISBN 9781444333503.

- Shaw, Ian. & Nicholson, Paul, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 109.

- Mitchell, Larkin. "Earliest Egyptian Glyphs". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Cooper, Jerrol S. (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. pp. 10–14. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Hartwig, Melinda K. (2014). A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 424–425. ISBN 9781444333503.

- Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. 15. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. 14. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Demand, Nancy H. (2011). The Mediterranean Context of Early Greek History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 69. ISBN 9781444342345.

- Collon, Dominique (1995). Ancient Near Eastern Art. University of California Press. pp. 51–53. ISBN 9780520203075.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 16.

- Teeter, Emily. "Before the pyramids: the origins of Egyptian civilization": 166. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rowlands, Michael J. (1987). Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780521251037.

- Scarre, Chris; Fagan, Brian M. (2016). Ancient Civilizations. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 9781317296089.

- Isler, Martin (2001). Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building the Egyptian Pyramids. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8061-3342-3.

- Kantor, Helene J. (1952). "Further Evidence for Early Mesopotamian Relations with Egypt". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 11 (4): 239–250. doi:10.1086/371099. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 542687.

- Kantor, Helene J. (1952). "Further Evidence for Early Mesopotamian Relations with Egypt". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 11 (4): 239–250. doi:10.1086/371099. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 542687.

- Isler, Martin (2001). Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building the Egyptian Pyramids. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8061-3342-3.

- Kantor, Helene J. (1952). "Further Evidence for Early Mesopotamian Relations with Egypt". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 11 (4): 239–250. doi:10.1086/371099. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 542687.

- Honoré, Emmanuelle. "Earliest Cylinder-Seal Glyptic in Egypt: From Greater Mesopotamia to Naqada". H. Hanna Ed., Preprints of the International Conference on Heritage of Naqada and Qus Region, Volume I.

- Demand, Nancy H. (2011). The Mediterranean Context of Early Greek History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 71–72. ISBN 9781444342345.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 18.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 17.

- Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. 20. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. 16. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Meador, Betty De Shong (2000). Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna. University of Texas Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9.

- Demand, Nancy H. (2011). The Mediterranean Context of Early Greek History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 71. ISBN 9781444342345.

- Silberman, Neil Asher. The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press USA. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5.

- Crüsemann, Nicola; Ess, Margarete van; Hilgert, Markus; Salje, Beate; Potts, Timothy (2019). Uruk: First City of the Ancient World. Getty Publications. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-60606-444-3.

- Samuels, Charlie (2010). Ancient Science (Prehistory – A.D. 500): Prehistory-A.D. 500. Gareth Stevens Publishing LLLP. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4339-4137-5.

- Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. 13. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. 17. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 20.

- Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt. p.6, Routledge, London. 1999. ISBN 0-203-20421-2.

- "British Museum notice".

- "Necklace British Museum". The British Museum.

- "Pendant British Museum". The British Museum.

- Miroschedji, Pierre de. Une palette égyptienne prédynastique du sud de la plaine côtière d'Israël.

- Early Dynastic Egypt (Routledge, 1999), p.15

- Redford, Donald B., Egypt, Israel, and Canaan in Ancient Times (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 13.

- Gardiner, Alan. Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1961), p. 392.

- Shaw, Ian. and Nicholson, Paul, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 228.

- "Because the reverse is not true, namely there is no trace of an Egyptian presence in Mesopotamia at that time, all seems to point to a flow of ideas from Mesopotamia to Egypt." "Earliest Egyptian Glyphs - Archaeology Magazine Archive". archive.archaeology.org.

- Louvre Museum AO 5359 Miroschedji, Pierre de. Une palette égyptienne prédynastique du sud de la plaine côtière d'Israël.

- Barraclough, Geoffrey; Stone, Norman (1989). The Times Atlas of World History. Hammond Incorporated. p. 53. ISBN 9780723003045.

- Senner, Wayne M. (1991). The Origins of Writing. University of Nebraska Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780803291676.

- Boudreau, Vincent (2004). The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780521838610.

- Geoffrey Sampson (1 January 1990). Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction. Stanford University Press. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-8047-1756-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- Geoffrey W. Bromiley (June 1995). The international standard Bible encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 1150–. ISBN 978-0-8028-3784-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards, et al., The Cambridge Ancient History (3d ed. 1970) pp. 43–44.

- Robert E. Krebs; Carolyn A. Krebs (December 2003). Groundbreaking scientific experiments, inventions, and discoveries of the ancient world. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-0-313-31342-4. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- Simson Najovits, Egypt, Trunk of the Tree: A Modern Survey of an Ancient Land, Algora Publishing, 2004, pp. 55–56.

- "The seal impressions, from various tombs, date even further back, to 3400 B.C. These dates challenge the commonly held belief that early logographs, pictographic symbols representing a specific place, object, or quantity, first evolved into more complex phonetic symbols in Mesopotamia." Mitchell, Larkin. "Earliest Egyptian Glyphs". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. –24–25. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Conference, William Foxwell Albright Centennial (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. p. –24–25. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Page, Thomas. "DNA discovery unlocks secrets of ancient Egyptians". CNN.

- Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (30 May 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

-

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (30 May 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (30 May 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824. -

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: "Our data seem to indicate close admixture and affinity at a much earlier date, which is unsurprising given the long and complex connections between Egypt and the Middle East. These connections date back to Prehistory and occurred at a variety of scales, including overland and maritime commerce, diplomacy, immigration, invasion and deportation" in Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (30 May 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: "Our data seem to indicate close admixture and affinity at a much earlier date, which is unsurprising given the long and complex connections between Egypt and the Middle East. These connections date back to Prehistory and occurred at a variety of scales, including overland and maritime commerce, diplomacy, immigration, invasion and deportation" in Krause, Johannes; Schiffels, Stephan (30 May 2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824. - Hartwig, Melinda K. (2014). A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 428–429. ISBN 9781444333503.

- Hartwig, Melinda K. (2014). A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. John Wiley & Sons. p. 428. ISBN 9781444333503.

- Hartwig, Melinda K. (2014). A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. John Wiley & Sons. p. 430. ISBN 9781444333503.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2014). "Tomb 197 at Abydos, Further Evidence for Long Distance Trade in the Middle Kingdom". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 24: 159–170. doi:10.1553/s159. JSTOR 43553796.

- Stevenson, Alice (2015). Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology: Characters and Collections. UCL Press. p. 54. ISBN 9781910634042.

- Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 131.

- Bard 2015, p. 188.

- Kamrin, Janice (2009). "The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. Vol. 1:3. S2CID 199601200.

- Mieroop, Marc Van De (2010). A History of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-4051-6070-4.

- Bard, Kathryn A. (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2.

- Rohl, David (2010). The Lords Of Avaris. Random House. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-4070-1092-2.

- Weigall, Arthur E. P. Brome (2016). A History of the Pharaohs. Cambridge University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-108-08291-4.

- "Statue British Museum". The British Museum.

- Hartwig, Melinda K. (2014). A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 424–425. ISBN 9781444333503.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)