Anna's hummingbird

Anna's hummingbird (Calypte anna) is a medium-sized bird species of the family Trochilidae. It was named after Anna Masséna, Duchess of Rivoli.[2]

| Anna's hummingbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male flying in California, USA | |

| |

| Female hovering | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae |

| Genus: | Calypte |

| Species: | C. anna |

| Binomial name | |

| Calypte anna (Lesson, 1829) | |

| |

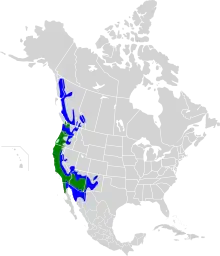

| Range of C. anna Wintering range Breeding and wintering range | |

It is native to western coastal regions of North America. In the early 20th century, Anna's hummingbirds bred only in northern Baja California and southern California. The transplanting of exotic ornamental plants in residential areas throughout the Pacific coast and inland deserts provided expanded nectar and nesting sites, allowing the species to expand its breeding range.[2][3]

Description

Anna's hummingbird is 3.9 to 4.3 in (9.9 to 10.9 cm) long with a wingspan of 4.7 in (12 cm) and a weight range of 0.1-0.2 oz (3-6 g).[4] It has an iridescent bronze-green back, a pale grey chest and belly, and green flanks. Its bill is long, straight, and slender. The adult male has an iridescent crimson-red derived from magenta to a reddish-pink crown and gorget, which can look dull brown or gray without direct sunlight and a dark, slightly forked tail. Females also have iridescent red gorgets, though they are usually smaller and less brilliant than the males'. Anna's is the only North American hummingbird species with a red crown.[3] Females and juvenile males have a dull green crown, a grey throat with or without some red iridescence, a grey chest and belly, and a dark, rounded tail with white tips on the outer feathers.

These birds feed on nectar from flowers using a long extendable tongue. They also consume small insects and other arthropods caught in flight or gleaned from vegetation. A PBS documentary shows how Anna's hummingbirds eat flying insects.[5] They aim for the flying insect, then open their beaks to capture the prey.

While collecting nectar, they also assist in plant pollination. This species sometimes consumes tree sap.[6] The male's call is scratchy and metallic, and it perches above head-level in trees and shrubs.[3] They are frequently seen in backyards and parks, and commonly found at feeders and flowering plants.

Anna's hummingbirds can shake their bodies 55 times per second to shed rain while in flight, or in dry weather, to remove pollen or dirt from feathers.[7] Each twist lasts four-hundredths of a second and applies 34 times the force of gravity on the bird's head.

Reproduction

Open-wooded or shrubby areas and mountain meadows along the Pacific coast from British Columbia to Arizona make up C. anna's breeding habitat. The female raises the young without the assistance of the male. The female bird builds a nest in a shrub or tree, in vines, or attached to wires or other artificial substrates. The round, 3.8-to-5.1-centimetre (1.5 to 2.0 in) diameter nest is constructed of plant fibers, downy feathers and animal hair; the exterior is camouflaged with chips of lichen, plant debris, and occasionally urban detritus such as paint chips and cigarette paper.[2] The nest materials are bound together with spider silk. They are known to nest as early as mid-December and as late as June, depending on geographic location and climatic conditions.[8][9]

Unlike most northern temperate hummingbirds, the male Anna's hummingbird sings during courtship. The song is thin and squeaky, interspersed with buzzes and chirps, and is drawn to over 10 seconds in duration. During the breeding season, males can be observed performing an aerial display dive over their territories. The males also use the dive display to drive away rivals or intruders of other species. When a female flies onto a male's territory, he rises up about 130 ft (40 m) before diving over the recipient. As he approaches the bottom of the dive, the male reaches an average speed of 27 m/s (89 ft/s), which is 385 body lengths per second.[10] At the bottom of the dive, the male travels 23 m/s (51 mph), and produces a loud sound described by some as an "explosive squeak" with his outer tail-feathers.[11][12]

Anna's hummingbirds hybridize fairly frequently with other species, especially the congeneric Costa's hummingbird.[2] These natural hybrids have been mistaken for new species. A bird, allegedly collected in Bolaños, Mexico, was described and named Selasphorus floresii (Gould, 1861), or Floresi's hummingbird. Several more specimens were collected in California over a long period, and the species was considered extremely rare.[13] The specimens were the hybrid offspring of an Anna's hummingbird and an Allen's hummingbird. A single bird collected in Santa Barbara, California, was described and named Trochilus violajugulum (Jeffries, 1888), or violet-throated hummingbird.[14] It was later determined to be a hybrid between an Anna's hummingbird and a black-chinned hummingbird.[15][16]

Locomotion

During hovering flight, Anna's hummingbirds maintain high wingbeat frequencies accomplished by their large pectoral muscles via recruitment of motor units.[17] The pectoral muscles that power hummingbird flight are composed exclusively of fast glycolytic fibers that respond rapidly and are fatigue-resistant.[17]

Distribution

Anna's hummingbirds are found along the western coast of North America, from southern Canada to northern Baja California, and inland to southern and central Arizona, extreme southern Nevada and southeastern Utah, and western Texas.[2] They tend to be permanent residents within their range, and are very territorial. However, birds have been spotted far outside their range in such places as southern Alaska, Saskatchewan, New York, Florida, Louisiana, and Newfoundland.[18][19]

While the species was originally restricted to the chaparral of California and Baja California, their range expanded north to Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, and east to Arizona in the 1960s and 70s. This rapid expansion can be attributed to the widespread planting of non-native species, such as eucalyptus, as well as the use of bird feeders, in combination with the species' natural tendency for extensive postbreeding dispersal.[8][20]

Anna's hummingbirds have the northernmost year-round range of any hummingbird. During cold temperatures, Anna's hummingbirds gradually gain weight during the day as they convert sugar to fat.[21][22] In addition, hummingbirds with inadequate stores of body fat or insufficient plumage are able to survive periods of subfreezing weather by lowering their metabolic rate and entering a state of torpor.[23]

The population of Anna's hummingbirds is an estimated 1.5 million, which appears to be stable, and they are not considered an endangered species.[1] In the 2017 Vancouver Official City Bird Election, Anna's hummingbird was named the official bird of the city of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada,[24] where it resides year round through winter.[25]

Gallery

Female feeding

Female feeding Male feeding

Male feeding A female

A female A male

A male A male showing his iridescent head

A male showing his iridescent head Adult male, singing

Adult male, singing Male flying

Male flying A juvenile

A juvenile

References

- BirdLife International 2016. Calypte anna. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22688199A93186783. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22688199A93186783.en. Downloaded on 21 March 2019.

- Williamson, Sheri (2001). A Field Guide to Hummingbirds of North America. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 199. ISBN 0-618-02496-4.

- "Anna's Hummingbird". Cornell University Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- "Anna's Hummingbird Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Hummingbirds: Magic in the Air (Video: Expert Hunters). Public Broadcasting Service. 10 January 2010. Video: Full Episode (at 16:45)

- Peterson, Roger Tory; Peterson, Virginia Marie (1990). Peterson's Field Guide to Western Birds. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 216–217. ISBN 0-395-51424-X.

- Ortega-Jimenez, VM; Dudley, R (2012). "Aerial shaking performance of wet Anna's hummingbirds". J R Soc Interface. 9 (70): 1093–1099. doi:10.1098/rsif.2011.0608. PMC 3306655. PMID 22072447.

- "Anna's Hummingbird - Introduction Birds of North America Online". birdsna.org. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- Sheri., Williamson (2001). A field guide to hummingbirds of North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0618024956. OCLC 46660593.

- Clark, C.J. (2009). "Courtship dives of Anna's hummingbird offer insights into flight performance limits". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 276 (1670): 3047–3052. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0508. PMC 2817121. PMID 19515669.

- Clark, C.J.; Feo, TJ (2008). "The Anna's Hummingbird chirps with its tail: a new mechanism of sonation in birds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 275 (1637): 955–62. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1619. PMC 2599939. PMID 18230592.

- Yollin, Patricia (8 February 2008). "How hummingbirds chirp: It's all in the tail". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Palmer, T.S. (September 1928). "Notes on persons whose names appear in the nomenclature of California birds" (PDF). The Condor. 30 (5): 277. doi:10.2307/1363227. JSTOR 1363227.

- Ridgway, Robert (1892). The Humming Birds. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 331, 329.

- Taylor, Walter P. (1909). "An instance of hybridization in hummingbirds, with remarks on the weight of generic characters in the Trochilidae". The Auk. 26 (3): 291–293. doi:10.2307/4070800. JSTOR 4070800.

- Ridgway, Robert (1909). "Hybridism and generic characters in the Trochilidae". The Auk. 26 (4): 440–442. doi:10.2307/4071292. JSTOR 4071292. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- Altshuler, Douglas L.; Welch, Kenneth C.; Cho, Brian H.; Welch, Danny B.; Lin, Amy F.; Dickson, William B.; Dickinson, Michael H. (2010-07-15). "Neuromuscular control of wingbeat kinematics in Anna's hummingbirds (Calypte anna)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (14): 2507–2514. doi:10.1242/jeb.043497. ISSN 0022-0949. PMC 2892424. PMID 20581280.

- "Unusual Hummingbird for Idaho: Anna's Hummingbird – Calypte anna". Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-11-12.. See distribution map on bottom of page.

- "Pacific hummingbird found in eastern NFLD". CBC News. 24 January 2011. Archived from the original on 21 November 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2016..

- Clark CJ, Russell SM (2012). "Anna's Hummingbird (Calypte anna)". The Birds of North America Online. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor), Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. doi:10.2173/bna.226.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Beuchat, C.A.; Chaplin, S.B.; Morton, M.L. (1979). "Ambient temperature and the daily energetics of two species of hummingbirds, Calypte anna and Selasphorus rufus". Physiol. Zool. 52 (3): 280–295. doi:10.1086/physzool.52.3.30155751.

- Powers, D. R. (1991). "Diurnal Variation in Mass, Metabolic Rate, and Respiratory Quotient in Anna's and Costa's Hummingbirds" (PDF). Physiological Zoology. 64 (3): 850–870. doi:10.1086/physzool.64.3.30158211. JSTOR 30158211.

- Russell, S.M. (1996). In The Birds of North America, No. 226 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and The American Ornithologists' Union, Washington DC

- "Official City Bird: Anna's Hummingbird". City of Vancouver. 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Gregory A Green (2 October 2018). "Anna's Hummingbird: Our winter hummingbird". BirdWatching. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anna's Hummingbird. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Calypte anna. |

- Anna's Hummingbird Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Explore Species: Anna's Hummingbird at eBird (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

- Anna's Hummingbird photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)