Antarctic ice sheet

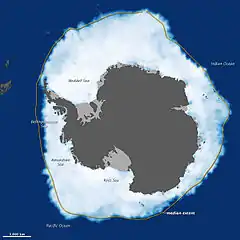

The Antarctic ice sheet is one of the two polar ice caps of the Earth. It covers about 98% of the Antarctic continent and is the largest single mass of ice on Earth. It covers an area of almost 14 million square kilometres (5.4 million square miles) and contains 26.5 million cubic kilometres (6,400,000 cubic miles) of ice.[2] A cubic kilometer of ice weighs approximately one metric gigaton, meaning that the ice sheet weighs 26,500,000 gigatons. Approximately 61 percent of all fresh water on the Earth is held in the Antarctic ice sheet, an amount equivalent to about 58 m of sea-level rise.[3] In East Antarctica, the ice sheet rests on a major land mass, while in West Antarctica the bed can extend to more than 2,500 m below sea level.

Satellite measurements by NASA indicate a still increasing sheet thickness above the continent, outweighing the losses at the edge.[4] The reasons for this are not fully understood, but suggestions include the climatic effects on ocean and atmospheric circulation of the ozone hole,[5] and/or cooler ocean surface temperatures as the warming deep waters melt the ice shelves.[6]

History

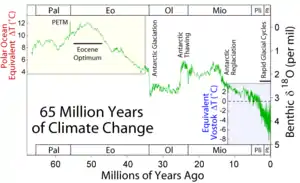

The icing of Antarctica began in the middle Eocene about 45.5 million years ago[7] and escalated during the Eocene–Oligocene extinction event about 34 million years ago. CO2 levels were then about 760 ppm[8] and had been decreasing from earlier levels in the thousands of ppm. Carbon dioxide decrease, with a tipping point of 600 ppm, was the primary agent forcing Antarctic glaciation.[9] The glaciation was favored by an interval when the Earth's orbit favored cool summers but oxygen isotope ratio cycle marker changes were too large to be explained by Antarctic ice-sheet growth alone indicating an ice age of some size.[10] The opening of the Drake Passage may have played a role as well[11] though models of the changes suggest declining CO2 levels to have been more important.[12]

The Western Antarctic ice sheet declined somewhat during the warm early Pliocene epoch, approximately 5 to 3 million years ago; during this time the Ross Sea opened up.[13] But there was no significant decline in the land-based Eastern Antarctic ice sheet.[14]

Changes since the late twentieth century

Temperature

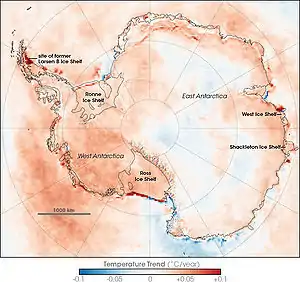

According to a 2009 study, the continent-wide average surface temperature trend of Antarctica is positive and significant at >0.05 °C/decade since 1957.[15][16][17][18] West Antarctica has warmed by more than 0.1 °C/decade in the last 50 years, and this warming is strongest in winter and spring. Although this is partly offset by fall cooling in East Antarctica, this effect is restricted to the 1980s and 1990s.[15][16][17]

Floating ice and land ice

Ice enters the sheet through precipitation as snow. This snow is then compacted to form glacier ice which moves under gravity towards the coast. Most of it is carried to the coast by fast moving ice streams. The ice then passes into the ocean, often forming vast floating ice shelves. These shelves then melt or calve off to give icebergs that eventually melt.

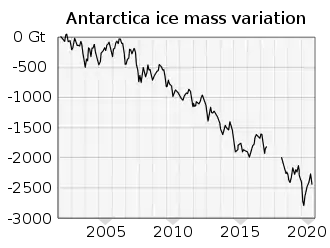

If the transfer of the ice from the land to the sea is balanced by snow falling back on the land then there will be no net contribution to global sea levels. The general trend shows that a warming climate in the southern hemisphere would transport more moisture to Antarctica, causing the interior ice sheets to grow, while calving events along the coast will increase, causing these areas to shrink. A 2006 paper derived from satellite data, measuring changes in the gravity of the ice mass, suggests that the total amount of ice in Antarctica has begun decreasing in the past few years.[19] A 2008 study compared the ice leaving the ice sheet, by measuring the ice velocity and thickness along the coast, to the amount of snow accumulation over the continent. This found that the East Antarctic Ice Sheet was in balance but the West Antarctic Ice Sheet was losing mass. This was largely due to acceleration of ice streams such as Pine Island Glacier. These results agree closely with the gravity changes.[20][21] An estimate published in November 2012 and based on the GRACE data as well as on an improved glacial isostatic adjustment model discussed systematic uncertainty in the estimates, and by studying 26 separate regions, estimated an average yearly mass loss of 69 ± 18 Gt/y from 2002 to 2010 (a sea-level rise of 0.16 ± 0.043 mm/y). The mass loss was geographically uneven, mainly occurring along the Amundsen Sea coast, while the West Antarctic Ice Sheet mass was roughly constant and the East Antarctic Ice Sheet gained in mass.[22]

Antarctic sea ice anomalies have roughly followed the pattern of warming, with the greatest declines occurring off the coast of West Antarctica. East Antarctica sea ice has been increasing since 1978, though not at a statistically significant rate. The atmospheric warming has been directly linked to the mass losses in West Antarctica of the first decade of the twenty-first century. This mass loss is more likely to be due to increased melting of the ice shelves because of changes in ocean circulation patterns (which themselves may be linked to atmospheric circulation changes that may also explain the warming trends in West Antarctica). Melting of the ice shelves in turn causes the ice streams to speed up.[23] The melting and disappearance of the floating ice shelves will only have a small effect on sea level, which is due to salinity differences.[24][25][26] The most important consequence of their increased melting is the speed up of the ice streams on land which are buttressed by these ice shelves.

Recent observations

A group of scientists with the University of California updated previous results ranging from 1979 to 2017, which improved time series for more accurate results. Their article, published January 2019, covered four decades of information in Antarctica, revealing the total mass loss which increased gradually per decade.

40 ± 9 Gt/y from 1979 to 1990, 50 ± 14 Gt/y from 1989 to 2000, 166 ±18 Gt/y from 1999 to 2009 and finally 252 ±26 Gt/y from 2009 to 2017. The majority of mass loss was in the Amundsen Sea sector, which experienced loss as high as 159 ±8 Gt/y. There are areas which have not experienced much loss at all, such as East Ross ice shelf.

This improved study revealed an acceleration of near 280% over the span of four decades. The study questions previous hypotheses, such as the belief that the heavy melt began in the 1940s to 1970s, suggesting that more recent anthropogenic actions have caused accelerated melt.[28]

See also

References

- NASA (2007). "Two Decades of Temperature Change in Antarctica". Earth Observatory Newsroom. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-14. NASA image by Robert Simmon, based on data from Joey Comiso, GSFC.

- Amos, Jonathan (2013-03-08). "BBC News - Antarctic ice volume measured". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- P. Fretwell; H. D. Pritchard; et al. (31 July 2012). "Bedmap2: improved ice bed, surface and thickness datasets for Antarctica" (PDF). The Cryosphere. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

Using data largely collected during the 1970s, Drewry et al. (1992), estimated the potential sea-level contribution of the Antarctic ice sheets to be in the range of 60-72 m; for Bedmap1 this value was 57 m (Lythe et al., 2001), and for Bedmap2 it is 58 m.

- https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/nasa-study-mass-gains-of-antarctic-ice-sheet-greater-than-losses

- Turner, John; Overland, Jim (2009). "Contrasting climate change in the two polar regions" (PDF). Polar Research. 28 (2). doi:10.3402/polar.v28i2.6120.

- Bintanja, R.; van Oldenborgh, G. J.; Drijfhout, S. S.; Wouters, B.; Katsman, C. A. (31 March 2013). "Important role for ocean warming and increased ice-shelf melt in Antarctic sea-ice expansion". Nature Geoscience. 6 (5): 376–379. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..376B. doi:10.1038/ngeo1767.

- Sedimentological evidence for the formation of an East Antarctic ice sheet in Eocene/Oligocene time Palaeogeography, palaeoclimatology, & palaeoecology ISSN 0031-0182, 1992, vol. 93, no1-2, pp. 85–112 (3 p.)

- New CO2 data helps unlock the secrets of Antarctic formation September 13th, 2009

- Pagani, M.; Huber, M.; Liu, Z.; Bohaty, S. M.; Henderiks, J.; Sijp, W.; Krishnan, S.; Deconto, R. M. (2011). "Drop in carbon dioxide levels led to polar ice sheet, study finds". Science. 334 (6060): 1261–1264. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1261P. doi:10.1126/science.1203909. PMID 22144622. S2CID 206533232. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- Coxall, Helen K. (2005). "Rapid stepwise onset of Antarctic glaciation and deeper calcite compensation in the Pacific Ocean". Nature. 433 (7021): 53–57. Bibcode:2005Natur.433...53C. doi:10.1038/nature03135. PMID 15635407. S2CID 830008.

- Diester-Haass, Liselotte; Zahn, Rainer (1996). "Eocene-Oligocene transition in the Southern Ocean: History of water mass circulation and biological productivity". Geology. 24 (2): 163. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1996)024<0163:EOTITS>2.3.CO;2.

- DeConto, Robert M. (2003). "Rapid Cenozoic glaciation of Antarctica induced by declining atmospheric CO2". Nature. 421 (6920): 245–249. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..245D. doi:10.1038/nature01290. PMID 12529638. S2CID 4326971.

- Naish, Timothy; et al. (2009). "Obliquity-paced Pliocene West Antarctic ice sheet oscillations". Nature. 458 (7236): 322–328. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..322N. doi:10.1038/nature07867. PMID 19295607. S2CID 15213187.

- Shakun, Jeremy D.; et al. (2018). "Minimal East Antarctic Ice Sheet retreat onto land during the past eight million years". Nature. 558 (7709): 284–287. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0155-6. PMID 29899483. S2CID 49185845.

- Steig, Eric (2009-01-21). "Temperature in West Antarctica over the last 50 and 200 years" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- Steig, Eric. "Biography". Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- Steig, E. J.; Schneider, D. P.; Rutherford, S. D.; Mann, M. E.; Comiso, J. C.; Shindell, D. T. (2009). "Warming of the Antarctic ice-sheet surface since the 1957 International Geophysical Year". Nature. 457 (7228): 459–462. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..459S. doi:10.1038/nature07669. PMID 19158794. S2CID 4410477.

- Ingham, Richard (2009-01-22). "Global warming hitting all of Antarctica". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- Velicogna, Isabella; Wahr, John; Scott, Jim (2006-03-02). "Antarctic ice sheet losing mass, says University of Colorado study". University of Colorado at Boulder. Archived from the original on 9 April 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-21. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rignot, E.; Bamber, J. L.; Van Den Broeke, M. R.; Davis, C.; Li, Y.; Van De Berg, W. J.; Van Meijgaard, E. (2008). "Recent Antarctic ice mass loss from radar interferometry and regional climate modelling". Nature Geoscience. 1 (2): 106. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..106R. doi:10.1038/ngeo102.

- Rignot, E. (2008). "Changes in West Antarctic ice stream dynamics observed with ALOS PALSAR data". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (12): L12505. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3512505R. doi:10.1029/2008GL033365.

- King, M. A.; Bingham, R. J.; Moore, P.; Whitehouse, P. L.; Bentley, M. J.; Milne, G. A. (2012). "Lower satellite-gravimetry estimates of Antarctic sea-level contribution". Nature. 491 (7425): 586–589. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..586K. doi:10.1038/nature11621. PMID 23086145. S2CID 4414976.

- Payne, A. J.; Vieli, A.; Shepherd, A. P.; Wingham, D. J.; Rignot, E. (2004). "Recent dramatic thinning of largest West Antarctic ice stream triggered by oceans". Geophysical Research Letters. 31 (23): L23401. Bibcode:2004GeoRL..3123401P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1001.6901. doi:10.1029/2004GL021284.

- Peter Noerdlinger, PHYSORG.COM "Melting of Floating Ice Will Raise Sea Level"

- Noerdlinger, P.D.; Brower, K.R. (July 2007). "The melting of floating ice raises the ocean level" (PDF). Geophysical Journal International. 170 (1): 145–150. Bibcode:2007GeoJI.170..145N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2007.03472.x.

- Jenkins, A.; Holland, D. (August 2007). "Melting of floating ice and sea level rise". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (16): L16609. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..3416609J. doi:10.1029/2007GL030784.

- "Facts / Vital signs / Ice Sheets / Antarctica Mass Variation Since 2002". climate.NASA.gov. NASA. 2020. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020.

- Rignot, Eric; Mouginot, Jérémie; Scheuchl, Bernd; van den Broeke, Michiel; van Wessem, Melchior J.; Morlighem, Mathieu (2019-01-22). "Four decades of Antarctic Ice Sheet mass balance from 1979–2017". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (4): 1095–1103. doi:10.1073/pnas.1812883116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6347714. PMID 30642972.