Anti-nihilistic novel

An anti-nihilistic novel[note 1] is a form of novel from late 19th-century Russian literature, that came as a reaction to the disillusioned attitudes of the Russian nihilist movement and revolutionary socialism of the 1860s and 1870s.[1] The genre was influential in shaping subsequent ideas on nihilism as a philosophy and cultural phenomenon.[2] Its name derives from the historical usage of the word nihilism as broadly applied to revolutionary movements within the Russian Empire at the time.

| Part of a series on |

| Nihilism |

|---|

|

|

In the more formulaic works of this genre, the typical protagonist is a nihilist student. However, in contrast to the Chernyshevskian character of Rakhmetov, the nihilist is weak-willed and is easily seduced into subversive activities by a villain, often a Pole (in reference to Polish insurrectionary efforts against the Russian Empire).[note 2][3] The more meritous works of this genre managed to explore nihilism with less caricature.[3] Many anti-nihilistic novels were published in the conservative literary magazine The Russian Messenger edited by Mikhail Katkov.[1]

Background

From the period 1860–1917, Russian nihilism was both a nascent form of nihilist philosophy and broad cultural movement which overlapped with certain revolutionary tendencies of the era,[4] for which it was often wrongly characterized as a form of political terrorism.[5] Russian nihilism centered on the dissolution of existing values and ideals, incorporating theories of hard determinism, atheism, materialism, positivism, and rational egoism, while rejecting metaphysics, sentimentalism, and aestheticism.[6] Leading philosophers of this school of thought included Nikolay Chernyshevsky and Dmitry Pisarev.[7]

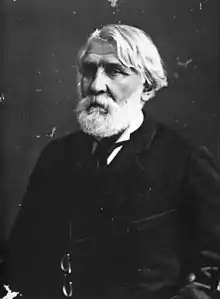

The intellectual origins of the Russian nihilist movement can be traced back to 1855 and perhaps earlier,[8] where it was principally a philosophy of extreme moral and epistemological skepticism.[9] However, it was not until 1862 that the name nihilism was first popularized, when Ivan Turgenev used the term in his celebrated novel Fathers and Sons to describe the disillusionment of the younger generation towards both the progressives and traditionalists that came before them,[10] as well as its manifestation in the view that negation and value-destruction were most necessary to the present conditions.[11] The movement very soon adopted the name, despite the novel's initial harsh reception among both the conservatives and younger generation.[12]

Though philosophically both nihilistic and skeptical, Russian nihilism did not unilaterally negate ethics and knowledge as may be assumed, nor did it espouse meaninglessness unequivocally.[13] Even so, contemporary scholarship has challenged the equating of Russian nihilism with mere skepticism, instead identifying it as a fundamentally Promethean movement.[14] As passionate advocates of negation, the nihilists sought to liberate the Promethean might of the Russian people which they saw embodied in a class of prototypal individuals, or new types in their own words.[15] These individuals, according to Pisarev, in freeing themselves from all authority become exempt from moral authority as well, and are distinguished above the rabble or common masses.[16]Nihilism came into conflict with Orthodox religious authorities, as well as with the Tsarist autocracy.[17] Young radicals began calling themselves nihilists in university protests, innocuous youthful rebellions, and ever-escalating revolutionary activities, which included widespread arson.[18] The theoretic side of nihilism was somewhat distinct from this violent expression however.[19] Nevertheless, nihilism was widely castigated by conservative publicists and government authorities.[20] Fathers and Sons is sometimes considered a more sympathetic work of the anti-nihilistic genre, as with Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov;[2] Turgenev's own opinion of his nihilist character Bazarov was ambivalent, stating: "Did I want to abuse Bazarov or extol him? I do not know myself, since I don't know whether I love him or hate him."[21]

List of anti-nihilistic novels

- Fathers and Sons (1862) by Ivan Turgenev[2]

- Troubled Seas (1863) by Aleksey Pisemsky[22][23]

- Obojdennye (1863) by Nikolai Leskov[24]

- No Way Out (1864) by Nikolai Leskov[23]

- Marevo (1864) by Viktor Klyushnikov[23]

- Notes from Underground (1864) by Fyodor Dostoevsky

- Sovremennaya Idilliya (1865) by Vasiliĭ Avenarius[24]

- Crime and Punishment (1866) by Fyodor Dostoevsky[2]

- Povetrie (1867) by Vasiliĭ Avenarius[24]

- Panurgovo Stado (1869) by Vsevoloda Krestovskogo[24]

- The Idiot (1869) by Fyodor Dostoevsky[24]

- At Daggers Drawn (1870) by Nikolai Leskov[24]

- Demons (1871) by Fyodor Dostoevsky[22]

- Dve Sily (1874) by Vsevoloda Krestovskogo[24]

- The Brothers Karamazov (1880) by Fyodor Dostoevsky[2]

Notes

- In Russian: антинигилистический роман (antinigilisticheskiy roman), from нигилизм (nigilizm) meaning 'nihilism'.

- See: Polish insurrection of 1830–31, and Polish insurrection of 1863.

References

- Тюнькин, К. И. "Антинигилисти́ческий Рома́н". Concise Literary Encyclopedia (in Russian). Archived from the original on September 10, 2018.

- Petrov, Kristian (2019). "'Strike out, right and left!': a conceptual-historical analysis of 1860s Russian nihilism and its notion of negation". Stud East Eur Thought. 71 (2): 73–97. doi:10.1007/s11212-019-09319-4.

- Ulam, Adam Bruno (1977). Prophets and Conspirators in Pre-Revolutionary Russia. p. 146. ISBN 1412832195.

-

- "Nihilism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Nihilism, (from Latin nihil, "nothing"), originally a philosophy of moral and epistemological skepticism that arose in 19th-century Russia during the early years of the reign of Tsar Alexander II.

- Pratt, Alan. "Nihilism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

In Russia, nihilism became identified with a loosely organized revolutionary movement (C.1860-1917) that rejected the authority of the state, church, and family.

- Lovell, Stephen (1998). "Nihilism, Russian". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor and Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-E072-1. ISBN 9780415250696.

Nihilism was a broad social and cultural movement as well as a doctrine.

- "Nihilism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Nihilism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

The philosophy of nihilism then began to be associated erroneously with the regicide of Alexander II (1881) and the political terror that was employed by those active at the time in clandestine organizations opposed to absolutism.

-

- Petrov, Kristian (2019). "'Strike out, right and left!': a conceptual-historical analysis of 1860s Russian nihilism and its notion of negation". Stud East Eur Thought. 71 (2): 73–97. doi:10.1007/s11212-019-09319-4. S2CID 150893870.

- Scanlan, James P. (1999). "The Case against Rational Egoism in Dostoevsky's Notes from Underground". Journal of the History of Ideas. University of Pennsylvania Press. 60 (3): 553–554. JSTOR 3654018.

- Lovell, Stephen (1998). "Nihilism, Russian". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor and Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-E072-1. ISBN 9780415250696.

The major theorists of Russian Nihilism were Nikolai Chernyshevskii and Dmitrii Pisarev, although their authority and influence extended well beyond the realm of theory.

-

- Lovell, Stephen (1998). "Nihilism, Russian". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor and Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-E072-1. ISBN 9780415250696.

Russian Nihilism is perhaps best regarded as the intellectual pool of the period 1855–66 out of which later radical movements emerged

- Nishitani, Keiji (1990). McCormick, Peter J. (ed.). The Self-Overcoming of Nihilism. Translated by Graham Parkes; with Setsuko Aihara. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791404382.

Nihilism and anarchism, which for a while would completely dominate the intelligentsia and become a major factor in the history of nineteenth-century Russia, emerged in the final years of the reign of Alexander I.

- Lovell, Stephen (1998). "Nihilism, Russian". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor and Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-E072-1. ISBN 9780415250696.

- "Nihilism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Nihilism, (from Latin nihil, "nothing"), originally a philosophy of moral and epistemological skepticism that arose in 19th-century Russia during the early years of the reign of Tsar Alexander II.

-

- Petrov, Kristian (2019). "'Strike out, right and left!': a conceptual-historical analysis of 1860s Russian nihilism and its notion of negation". Stud East Eur Thought. 71 (2): 73–97. doi:10.1007/s11212-019-09319-4. S2CID 150893870.

Even so, the term nihilism did not become popular until Turgenev published F&C in 1862. Turgenev, a sorokovnik (an 1840s man), used the term to describe "the children", the new generation of students and intellectuals who, by virtue of their relation to their fathers, were considered šestidesjatniki.

- "Nihilism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

It was Ivan Turgenev, in his celebrated novel Fathers and Sons (1862), who popularized the term through the figure of Bazarov the nihilist.

- "Fathers and Sons". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Fathers and Sons concerns the inevitable conflict between generations and between the values of traditionalists and intellectuals.

- Edie, James M.; Scanlan, James; Zeldin, Mary-Barbara (1994). Russian Philosophy Volume II: the Nihilists, The Populists, Critics of Religion and Culture. University of Tennessee Press. p. 3.

The "fathers" of the novel are full of humanitarian, progressive sentiments ... But to the "sons," typified by the brusque scientifically minded Bazarov, the "fathers" were concerned too much with generalities, not enough with the specific material evils of the day.

- Petrov, Kristian (2019). "'Strike out, right and left!': a conceptual-historical analysis of 1860s Russian nihilism and its notion of negation". Stud East Eur Thought. 71 (2): 73–97. doi:10.1007/s11212-019-09319-4. S2CID 150893870.

- Frank, Joseph (1995). Dostoevsky: The Miraculous Years, 1865–1871. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01587-2.

For it was Bazarov who had first declared himself to be a "Nihilist" and who announced that, "since at the present time, negation is the most useful of all," the Nihilists "deny—everything."

-

- "Fathers and Sons". Encyclopædia Britannica.

At the novel's first appearance, the radical younger generation attacked it bitterly as a slander, and conservatives condemned it as too lenient

- "Fathers and Sons". Novels for Students. Retrieved August 11, 2020 – via Encyclopedia.com.

when he returned to Saint Petersburg in 1862 on the same day that young radicals—calling themselves "nihilists"—were setting fire to buildings

- "Fathers and Sons". Encyclopædia Britannica.

-

- "Nihilism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

originally a philosophy of moral and epistemological skepticism that arose in 19th-century Russia during the early years of the reign of Tsar Alexander II.

- Petrov, Kristian (2019). "'Strike out, right and left!': a conceptual-historical analysis of 1860s Russian nihilism and its notion of negation". Stud East Eur Thought. 71 (2): 73–97. doi:10.1007/s11212-019-09319-4. S2CID 150893870.

Russian nihilism did not imply, as one might expect from a purely semantic viewpoint, a universal "negation" of ethical normativity, the foundations of knowledge or the meaningfulness of human existence.

- "Nihilism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Gillespie, Michael Allen (1996). Nihilism Before Nietzsche. University of Chicago Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780226293486.

This nihilist movement was essentially Promethean"; "It has often been argued that Russian nihilism is little more than skepticism or empiricism. While there is a certain plausibility to this assertation, it ultimately fails to capture the millenarian zeal the characterized Russian nihilism. These nihilists were not skeptics but passionate advocates of negation and liberation.

-

- Gillespie, Michael Allen (1996). Nihilism Before Nietzsche. University of Chicago Press. pp. 139, 143–144. ISBN 9780226293486.

These nihilists were not skeptics but passionate advocates of negation and liberation."; "While the two leading nihilist groups disagreed on details, they both sought to liberate the Promethean might of the Russian people"; "The nihilists believed that the prototypes of this new Promethean humanity already existed in the cadre of the revolutionary movement itself.

- Petrov, Kristian (2019). "'Strike out, right and left!': a conceptual-historical analysis of 1860s Russian nihilism and its notion of negation". Stud East Eur Thought. 71 (2): 73–97. doi:10.1007/s11212-019-09319-4. S2CID 150893870.

These "new types", to borrow Pisarev’s designation

- Gillespie, Michael Allen (1996). Nihilism Before Nietzsche. University of Chicago Press. pp. 139, 143–144. ISBN 9780226293486.

- Frank, Joseph (1995). Dostoevsky: The Miraculous Years, 1865–1871. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01587-2.

- "Nihilism". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Since nihilists denied the duality of human beings as a combination of body and soul, of spiritual and material substance, they came into violent conflict with ecclesiastical authorities. Since nihilists questioned the doctrine of the divine right of kings, they came into similar conflict with secular authorities.

-

- Edie, James M.; Scanlan, James; Zeldin, Mary-Barbara (1994). Russian Philosophy Volume II: the Nihilists, The Populists, Critics of Religion and Culture. University of Tennessee Press. p. 6.

among the Russian students who used the name "Nihilism" to dignify youthful rebelliousness, this rejection of traditional standards went still further, expressing itself in everything from harmless crudities of dress and behaviour to the lethal fanaticism of a revolutionary like Sergey Nechayev.

- "Fathers and Sons". Novels for Students. Retrieved August 11, 2020 – via Encyclopedia.com.

young radicals, who claimed the term "nihilist" for themselves, and used it in their violent protests."; "when he returned to Saint Petersburg in 1862 on the same day that young radicals—calling themselves "nihilists"—were setting fire to buildings

- St. John Murphy, Sasha (2016). "The Debate around Nihilism in 1860s Russian Literature" (PDF). Slovo. 28 (2): 48–68. doi:10.14324/111.0954-6839.045.

The city of St. Petersburg erupted in flames in the spring and summer of 1862. Students of St. Petersburg and Moscow Universities, acting on an upsurge of revolutionary activism, had begun demonstrating their frustrations.

- Buel, James (1883). "Chapter 5". Russian Nihilism and Exile Life in Siberia. St. Louis, MO: Historical Publishing Co. p. 95.

In 1863 Poland, that had dreamed of an untrampled autonomy, at least since 1815, became the scene of a bloody insurrection, while all over Russia blazed up incendiary fires, and St. Petersburg was threatened with destruction.

- Edie, James M.; Scanlan, James; Zeldin, Mary-Barbara (1994). Russian Philosophy Volume II: the Nihilists, The Populists, Critics of Religion and Culture. University of Tennessee Press. p. 6.

- Edie, James M.; Scanlan, James; Zeldin, Mary-Barbara (1994). Russian Philosophy Volume II: the Nihilists, The Populists, Critics of Religion and Culture. University of Tennessee Press. p. 6.

- "Nihilism". The Great Soviet Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). 1970–1979. Retrieved September 23, 2020 – via TheFreeDictionary.com.

Reactionary publicistic writers seized upon the term during a lull in the revolutionary situation and used it as a derisive epithet. As such, it was extensively employed in publicistic articles, official government documents, and antinihilistic novels

- Gillespie, Michael Allen (1996). Nihilism Before Nietzsche. University of Chicago Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780226293486.

Turgenev's own opinion of Bazarov was ambivalent. "Did I want to abuse Bazarov or extol him? I do not know myself, since I don't know whether I love him or hate him!" (FAS, 184; cf 190).

- "Демифологизация русской интеллигенции". Нева (in Russian). No. 8. 2007.

- "Nihilism". The Great Soviet Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). 1970–1979. Retrieved October 1, 2020 – via TheFreeDictionary.com.

and antinihilistic novels, notably A. F. Pisemskii’s Troubled Seas, N. S. Leskov’s Nowhere to Go, and V. P. Kliushnikov’s The Mirage

- Батюто, А. И. (1982). "Антинигилистический роман". История русской литературы (in Russian). 3. Наука. Ленинградское отделение. pp. 279–314.

Further reading

- Moser, Charles A. (1964). Anti-Nihilism in the Russian Novel of the 1860s. The Hague.