Antichrist (film)

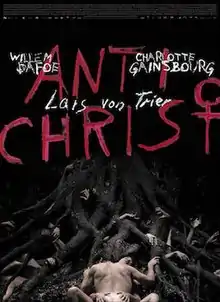

Antichrist is a 2009 experimental psychological horror film written and directed by Lars von Trier and starring Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg. It tells the story of a couple who, after the death of their child, retreat to a cabin in the woods where the man experiences strange visions and the woman manifests increasingly violent sexual behaviour and sadomasochism. The narrative is divided into a prologue, four chapters and an epilogue.

| Antichrist | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Lars von Trier |

| Produced by | Meta Louise Foldager |

| Written by | Lars von Trier |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Kristian Eidnes Andersen |

| Cinematography | Anthony Dod Mantle |

| Edited by |

|

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Nordisk Film Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes[2] |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.4 million[4] |

| Box office | $7.4 million[5] |

Written in 2006 while von Trier had been hospitalised due to a significant depressive episode, the film was largely influenced by his own struggles with depression and anxiety. Filming began in the late summer of 2008, primarily in Germany, and was a Danish production co-produced by several other film production companies from six different European countries.

After its premiere at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival, where Gainsbourg won the festival's award for Best Actress, the film immediately caused controversy, with critics generally praising its artistic execution but remaining strongly divided regarding its substantive merit. Other awards won by the film include the Robert Award for best Danish film, The Nordic Council Film Prize for best Nordic film and the European Film Award for best cinematography. The film is dedicated to the Soviet filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky (1932–86).

Antichrist is the first film in von Trier's unofficially titled Depression Trilogy. It was followed in 2011 by Melancholia and then by Nymphomaniac in 2013.[6]

Plot

A couple has sex in their Seattle, Washington apartment while their toddler son, Nic, climbs up to the bedroom window and falls to his death. The mother collapses at the funeral, and spends the next month in the hospital crippled with atypical grief. The father, a therapist, is skeptical of the psychiatric care she is receiving and takes it upon himself to treat her personally with psychotherapy. She reveals that her second greatest fear is nature, prompting him to try exposure therapy. They hike to their isolated cabin in a woods called Eden, where she spent time with Nic the previous summer while writing a thesis on gynocide. During the hike, he encounters a doe which shows no fear of him and has a stillborn fawn hanging halfway out of her.

During sessions of psychotherapy, she becomes increasingly grief-stricken and manic, often demanding forceful sex. The area becomes increasingly sinister to the man; acorns rapidly pelt the metal roof, he wakes up with a hand covered in swollen ticks, and he finds a self-disemboweling fox that tells him "chaos reigns."

In the dark attic the man finds the woman's thesis studies, which includes violent portraits of witch-hunts, and a scrapbook in which her writing becomes increasingly frantic and illegible. She reveals that while writing her thesis, she came to believe that all women are inherently evil. The man is repulsed by this and reproaches her for imbibing the gynocidal beliefs she had originally set out to criticize. In a frenzied moment, they have violent intercourse at the base of an ominous dead tree, where bodies are intertwined within the exposed roots. He suspects that Satan is her greatest hidden fear.

Upon viewing Nic's autopsy and photos she took of him while the two stayed at Eden, the man becomes aware that she had been systematically putting Nic's shoes on the wrong feet, resulting in a foot deformity. While in the woodshed, she attacks him, accuses him of planning to leave her, mounts him, and then smashes a large block of wood onto his groin, causing him to lose consciousness. The woman then masturbates the unconscious man, culminating in an ejaculation of blood. She drills a hole through his leg, bolting a heavy grindstone through the wound, and tosses the wrench she used under the cabin. He awakens alone; unable to loosen the bolt, he hides by dragging himself into a deep foxhole at the base of the dead tree. Following the sound of a crow he has found buried alive in the hole, she locates him and attacks and mostly buries him with a shovel.

Night falls; now remorseful, she unburies him but cannot remember where the wrench is. She helps him back to the cabin, where she tells him she does "not yet" want to kill him, adding that "when the three beggars arrive someone must die." In a flashback, she recounts Nic climbing up to the window, but she does not act, thus displaying her perceived essential evil. In the cabin, she cuts off her clitoris with scissors. The two are then visited by the crow, the deer, and the fox, the three beggars. A hailstorm begins; earlier it had been revealed that women accused of witchcraft had been known to have the power to summon hailstorms. When he finds the wrench under the cabin's floorboards, she attacks him with scissors, but he manages to unbolt the grindstone. Finally free, he viciously attacks her and strangles her to death. He then burns her on a funeral pyre.

He limps from the cabin, eating wild berries, as the three beggars look on, now translucent and glowing. Reaching the top of a hill, under a brilliant light he watches in awe as hundreds of women in antiquated clothes come towards him, their faces blurred.

Analysis

Nature and religion

Film scholar Magdalena Zolkos interprets Antichrist as an "origins story," citing its unnamed characters and setting—a woods called Eden—as primary reasons.[7] Zolkos's interpretation of the film aligns with that of scholar Joanne Bourke, who cites the film as a retelling of Abrahamic mythology "framed as a question."[1] The couple's entrance into the woods and arrival at Eden "initiates a cinematic restaging of the myths of origins."[8] The woman's statement made to her husband—that nature is "Satan's church"—suggests a "triadic nexus of nature, demonic force and the death of the child."[9] Zolkos characterizes this nexus as being made of three "separate, psychic events: the inscrutable and threatening surroundings of the forest; her readings in the history of religious misogyny; and an accident when she loses the child in the woods a year before his death."[9]

Zolkos also notes the film as a "story of parental loss and the mourning and despair that follows."[1]

Depression and mental illness

While the film interweaves multiple themes in Zolkos's reading, she suggests that the film is fundamentally a "very personal and revealing film—interwoven with idioms and images that document von Trier's struggle with serious psychiatric disorder, and highly informed by his experience of cognitive behaviour and exposure therapy, shamanism and Jungian psychoanalysis."[10] Von Trier himself commented on the experience of making the film as being a "fun" way of working through his own depression.[11] Von Trier considers the film the first of his "Depression Trilogy," followed by Melancholia (2011) and Nymphomaniac (2013).[12]

Scholar Amy Simmons notes that the film's aesthetic components "transcend categories, and as such, his work cannot be reduced to any one message."[13] She considers the film a "genuinely radical and unflinching account of human relationships."[14] Robert Sinnerbrink interprets the film (along with Melancholia and Nymphomaniac) as engaging with human responses to psychological trauma.[15] He explains: "In each case, there is a central female protagonist whose melancholic responses to this central trauma open up a space of subjective but also aesthetic-expressive engagement... In Antichrist, it is evident in the woman's intense anxiety and depressive withdrawal expressed through the neo-romantic landscape and supernaturalist elements of the forest to which she and her partner have retreated."[16]

Production

Development

Von Trier began writing Antichrist in 2006 while being hospitalised for depression.[17] Von Trier conceived the film as a horror film, as he felt it allowed for "a lot of very, very strange images."[18] He had recently seen several contemporary Japanese horror films such as Ring and Dark Water, from which he drew inspiration.[18] Another basic idea came from a documentary von Trier saw about the original forests of Europe. In the documentary the forests were portrayed as a place of great pain and suffering as the different species tried to kill and eat each other. Von Trier was fascinated by the contrast between this and the view of nature as a romantic and peaceful place. Von Trier said: "At the same time that we hang it on our walls over the fireplace or whatever, it represents pure Hell."[19] In retrospect he said that he had become unsure whether Antichrist really could be classified as a horror film, because "it's not so horrific ... we didn't try so hard to do shocks, and that is maybe why it is not a horror film. I took [the horror genre] more as an inspiration, and then this strange story came out of it."[18]

The title was the first thing that was written for the film.[20] Antichrist was originally scheduled for production in 2005, but its executive producer Peter Aalbæk Jensen accidentally revealed the film's planned revelation: that earth was created by Satan and not by God. Von Trier was furious and decided to delay the shoot so he could rewrite the script.[21]

In 2007, von Trier announced that he was suffering from depression, and that it was possible that he never would be able to make another film. "I assume that Antichrist will be my next film. But right now I don't know," he told the Danish newspaper Politiken.[22] During an early casting attempt, English actors who had come to Copenhagen had to be sent home, while von Trier was crying because his poor condition did not allow him to meet them.[23]

The post-depression version of the script was to some extent written as an exercise for von Trier, to see if he had recovered enough to be able to work again. Von Trier has also made references to August Strindberg and his Inferno Crisis in the 1890s, comparing it to his own writing under difficult mental circumstances: "was Antichrist my Inferno Crisis?"[20] Several notable names appear in the credits as having assisted von Trier in the writing. Danish writer and directors Per Fly and Nikolaj Arcel are listed as script consultants, and Anders Thomas Jensen as story supervisor. Also credited are researchers dedicated to fields including "misogyny", "anxiety", "horror films" and "theology."[24] Von Trier himself is a Catholic convert and intensely interested in Christian symbolism and theology.[25]

Production was led by von Trier's Copenhagen-based company Zentropa. Co-producers were Sweden's Film i Väst, Italy's Lucky Red and France's Liberator Productions, Slot Machine and Arte France. The Danish Film Institute contributed with a financial support of $1.5 million and Filmstiftung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Germany with $1.3 million. The total budget was around $11 million.[4]

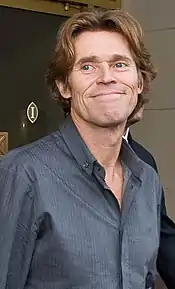

Pre-production

Props for the more violent scenes were provided by the company Soda ApS, and made in their workshop in Nørrebro, Copenhagen. Plaster casts were made of Willem Dafoe's leg and the female "porno double's" vulva. A plastic baby with authentic weight was made for the opening sequence. Pictures found using Google Image Search had to serve as models for the stillborn deer, and a nylon stocking was used as caul. The vulva prop was constructed with its inner parts detachable for easy preparation if several takes would be needed.[26] Czech animal trainer Ota Bares, who had collaborated with parts of the crew in the 2005 film Adam's Apples, was hired early on and given instructions about what tasks the animals must be able to perform. The fox, for example, was taught to open its mouth on a given command to simulate speaking movements.[27]

To get into the right mood before filming started, both Dafoe and Gainsbourg were shown Andrei Tarkovsky's The Mirror from 1975. Dafoe was also shown von Trier's own 1998 film The Idiots, and Gainsbourg The Night Porter to study Charlotte Rampling's character.[28] Dafoe also met therapists working with cognitive behavioral therapy as well as being present at actual sessions of exposure therapy and studying material on the topic.[29]

Casting

Willem Dafoe, who had previously worked with Lars von Trier in Manderlay (2005), was cast as "He" after contacting von Trier and asking what he was working on at the moment. He received the script for Antichrist, although he was told that von Trier's wife was skeptical about asking a renowned actor like Dafoe to do such an extreme role. Dafoe accepted the part, later explaining its appeal to him: "I think the dark stuff, the unspoken stuff is more potent for an actor. It's the stuff we don't talk about, so if you have the opportunity to apply yourself to that stuff in a playful, creative way, yes I'm attracted to it."[29] The voice of the talking fox was also supplied by Dafoe, although the recording was heavily manipulated.[19]

In casting the role of "She", actress Eva Green had been initially approached for the female lead. According to von Trier, Green was determined to appear in the film, but her agents refused to allow her. The unsuccessful casting attempt took two months of the pre-production process. Eventually, Charlotte Gainsbourg expressed interest in the role, and by von Trier's words she was very eager to get cast: "Charlotte came in and said, 'I'm dying to get the part no matter what.' So I think it was a decision she made very early and she stuck to it. We had no problems whatsoever."[30] Gainsbourg recalled upon first meeting von Trier that she had "known his films," but knew "very little about the man himself," and noted his presence as being "filled with anxiety" upon their first meeting.[31] She also initially expressed worry over the film's more emotional sequences, particularly surrounding her character's panic attacks and anxiety, as they were not things she had experienced in her own life.[31]

In the role of Nic, the child of the unnamed couple, Storm Acheche Sahlstrøm was cast.

Filming

Filming took 40 days to finish, from 20 August to the end of September 2008. The film was shot in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. Locations were used in Rhein-Sieg-Kreis, part of the Cologne region (including rural areas in Nutscheid)[32] and Wuppertal. It was the first film by von Trier to be entirely filmed in Germany.[33] The fictional setting of the film however is near Seattle, USA. The film was shot on digital video, primarily using Red One cameras in 4K resolution. The slow motion sequences were shot with a Phantom V4 in 1,000 frames per second. Filming techniques involved dollys, hand-held camerawork and computer-programmed "motion control", of which the team had previous experience from von Trier's 2006 film The Boss of It All. One shot, where the couple is copulating under a tree, was particularly difficult since the camera would switch from being hand-held to motion controlled in the middle of the take.[27]

Von Trier had not recovered completely from his depression when filming started. He repeatedly excused himself to the actors for being in the mental condition he was, and was not able to operate the camera as he usually does, which made him very frustrated.[23][28] "The script was filmed and finished without much enthusiasm, made as it was using about half of my physical and intellectual capacity," the director said in an interview.[20] Gainsbourg recalled that von Trier provided little direction during the shoot, but characterized the filming process as freeing and allowing room for both herself and Dafoe to experiment with varying performance styles.[31]

Post-production

Post-production was primarily located in Warsaw, Poland, and Gothenburg, Sweden. Over the time of two months, the Poles contributed with about 4,000 hours of work and the Swedes 500.[27] The film features 80 shots with computer-generated imagery, provided by the Polish company Platige Image. Most of these shots consist of digitally removed details such as the collar and leash used to lead the deer, but some were more complicated. The scene where the fox utters the words "chaos reigns" was particularly difficult to make. The mouth movements had to be entirely computer-generated in order to synchronise with the sound.[34] The sex scene in Chapter Three during which numerous hands emerge from the roots of a tree was subsequently adapted into the principal promotional art for the film.

Music

The aria "Lascia ch'io pianga" from Handel's opera Rinaldo is used as the film's main musical theme.[35] The aria has previously been used in other films such as Farinelli, a 1994 biographical film about the castrato singer Farinelli,[36] and was used again by von Trier in Nymphomaniac during a scene referencing the sequence showing Nic approaching the open window.[37] The eight-track soundtrack features both versions of "Lascia ch'io pianga" and selected extracts of the "score" created by sound designer Kristian Eidnes Andersen.

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Intro" | Kristian Eidnes Andersen | 1:32 |

| 2. | "Lascia Ch'io Pianga Prologue" | George Frideric Handel | 5:20 |

| 3. | "Train" | Kristian Eidnes | 0:41 |

| 4. | "Foetus" | Kristian Eidnes | 1:28 |

| 5. | "Attic" | Kristian Eidnes | 1:32 |

| 6. | "Lascia Ch'io Pianga Epilogue" | George Frideric Handel | 2:39 |

| 7. | "Credits Pt. 1" | Kristian Eidnes | 1:16 |

| 8. | "Credits Pt. 2" | Kristian Eidnes | 3:29 |

Release

The film premiered during the Competition portion of the 2009 Cannes Film Festival to a polarized response from the audience.[38][39][40] The film prompted several walk outs and at least four people fainted during the preview due to the film's explicit violence.[41] At the press conference following the screening, Trier was asked by a journalist from the Daily Mail to justify why he made the film, to which the director responded that he found the question strange since he considered the audience as his guests, "not the other way around." He then claimed to be the best director in the world.[42] Charlotte Gainsbourg won the Cannes Film Festival's award for Best Actress.[38] The ecumenical jury at the Cannes festival gave the film a special "anti-award" and declared the film to be "the most misogynist movie from the self-proclaimed biggest director in the world."[41] Cannes festival director Thierry Frémaux responded that this was a "ridiculous decision that borders on a call for censorship" and that it was "scandalous coming from an 'ecumenical' jury".[43] The "talking fox" was nominated for the Palm Dog, but lost to Dug from Up.[44]

Ratings and censorship

Two versions were available for buyers at the Cannes film market, nicknamed the "Catholic" and "Protestant" versions, where the former had some of the most explicit scenes removed while the latter was uncut.[45] The uncut version was released theatrically to a general audience on 20 May 2009 in Denmark. It was acquired for British distribution by Artificial Eye and American by IFC Films.[46] In the United Kingdom, it had a limited release beginning on 24 July 2009, and in the United States on 23 October 2009.[47][48] The film was not submitted to the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), and released unrated in the United States.[49] In both Ireland and the United Kingdom, Antichrist was also released uncut, bearing an 18 certificate.[50] David Cooke of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) commented on the decision to leave the film uncut, saying:

The film does not contain material which breaches the law or poses a significant harm risk to adults. The sexual imagery, while strong, is relatively brief, and the Board has passed a number works containing such images. This reflects the principle that adults should be free to decide for themselves what to watch or what not to watch, provided it is neither illegal nor harmful. There is no doubt that some viewers will find the images disturbing and offensive, but the BBFC's consumer advice provides a clear warning to enable individuals to make an informed viewing choice.[51]

The British Advertising Standards Authority received seven complaints about the film poster, which was based on the original poster and shows the couple as they are having sexual intercourse. The organization decided to approve the poster, finding it to not be pornographic since its "dark tone" made it "unlikely to cause sexual excitement". An alternative poster, featuring only quotes from reviews and no image at all, was used in outdoor venues and as an alternative for publishers who desired it.[52]

In 2016, seven years after its original release, the film was banned in France when the Catholic traditionalist group, Promouvoir, campaigned for a ratings reclassification of it.[53] The ruling French court deemed the culture ministry's original decision to release the film "a mistake."[53]

The film was not submitted to the MPAA because the filmmakers expected an NC-17 rating for its graphic violence and sex.[54]

Critical response

In Denmark, the film quickly became successful with both critics and audiences.[55][56] Politiken called it "a grotesque masterpiece," giving it a perfect score of 6 out of 6, and praised it for being completely unconventional while at the same time being "a profoundly serious, very personal ... piece of art about small things like sorrow, death, sex and the meaninglessness of everything."[57] Berlingske Tidende gave it a rating of 4 out of 6 and praised the "peerless imagery," and how "cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle effectively switches between Dogme-like hand-held scenes and wonderful stylized tableaux."[58] An exception was Claus Christensen, editor of the Danish film magazine Ekko. Christensen accused the other Danish critics of overrating the film, himself calling it "a master director's failed work."[59] Around 83,000 tickets were sold in Denmark during the theatrical run, the best performance by a von Trier film since Dogville.[60] The film was nominated by Denmark for The Nordic Council Film Prize, which it won.[61] Antichrist went on to sweep the Robert Awards, Denmark's main national film awards, by winning in seven categories: Best Film, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Cinematographer, Best Editing, Best Lighting Design and Best Special Effects.[62]

However, Antichrist polarized critical opinion in the United States. On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 53% based on 174 reviews, and an average rating of 5.56/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Gruesome, explicit and highly controversial; Lars von Trier's arthouse-horror, though beautifully shot, is no easy ride."[63] On Metacritic, the film has an average weighted score of 49 out of 100, based on 34 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[64] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four, saying:

Von Trier, who has always been a provocateur, is driven to confront and shake his audience more than any other serious filmmaker. He will do this with sex, pain, boredom, theology and bizarre stylistic experiments. And why not? We are at least convinced we're watching a film precisely as he intended it, and not after a watering down by a fearful studio executive. That said, I know what's in it for Von Trier. What was in it for me? More than anything else, I responded to the performances. Feature films may be fiction, but they are certainly documentaries showing actors in front of a camera.[65]

In a blog post, he expanded on this, discussing the film's symbolism, imagery and Trier's intentions, calling him "one of the most heroic directors in the world" and Antichrist "a powerfully-made film that contains material many audiences will find repulsive or unbearable. The performances by Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg are heroic and fearless. Trier's visual command is striking. The use of music is evocative; no score, but operatic and liturgical arias. And if you can think beyond what he shows to what he implies, its depth are [sic] frightening."[25]

Betsy Sharkey of the Los Angeles Times wrote: "The story of Antichrist is a tangled mess of sex, evil and death, with Von Trier making a stab at allegory and old-fashioned horror, but ultimately failing on both fronts... You might think, given the He, She, Eden, etc., that the film is allegory. It is not. Antichrist never rises to the symbolic; instead, it looks like nothing more than a reflection of one man's unresolved issues with the sexual liberation of women."[47] Duane Dudek of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel called Antichrist "Trier's most visually lush and technically rigorous film; it captures things at a molecular level and in a slow motion that all but brings the world to a halt... But paradoxically, this is his most unwatchable film, and many will find its violence and cruelty, including scenes of genital mutilation, repellent. I cannot recommend Antichrist, but in a culture that hemorrhages death and torture nightly on shows like 24 or C.S.I., I can understand it."[66]

Arguments for censorship were common in the British press, with much criticism rooted in the EU funding the film received.[67] Despite some controversy, the film was critically well-received in the British film magazine Empire, where film critic Kim Newman gave the film four stars out of five. He noted that "Trier's self-conscious arrogance is calculated to split audiences into extremist factions, but Antichrist delivers enough beauty, terror and wonder to qualify as the strangest and most original horror movie of the year."[68]

In Australia's The Monthly, film critic Luke Davies viewed it as "a bleak but entrancing film that explores guilt, grief and many things besides ... that will anger as many people as it pleases", describing Trier's "command of the visually surreal" as "truly exceptional". Davies described the film as "very good and very flawed", conceding "it is not easy to understand the meaning or intention of specific images and details of the film" but still concludes that "there's something neurotic and reactionary in the controversy and near-hysteria surrounding the film."[69]

Film director John Waters hailed Antichrist as one of the ten best films of 2009 in Artforum, stating "If Ingmar Bergman had committed suicide, gone to hell, and come back to earth to direct an exploitation/art film for drive-ins, [Antichrist] is the movie he would have made."[70]

The movie won the award for Best Cinematographer at the 2009 European Film Awards, shared with Slumdog Millionaire as both films were shot by Anthony Dod Mantle. It was nominated for Best Director and Best Actress but the awards lost to Michael Haneke for The White Ribbon and Kate Winslet for The Reader respectively.[71] In a 2016 international poll by BBC, critics Stephanie Zacharek and Andreas Borcholte ranked Antichrist among the greatest films since 2000.[72]

Home media

The film was given a DVD release in Australia in early 2010; sale of the DVD was strictly limited in South Australia due to new laws that place restrictions on films with an R18+ classification.[73] A notable feature of the Australian release was the creation of a critically acclaimed poster that made prominent use of a pair of rusty scissors that had the actor's faces fused into the handles. The poster received much international coverage at the end of 2009 and was used as the local DVD cover.

This film was released on DVD and Blu-ray in the United States through The Criterion Collection on 9 November 2010.[74]

Accolades

| Organization | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgian Syndicate of Cinema Critics | Grand Prix | Antichrist | Won |

| Bodil Awards | Best Danish Film | Lars von Trier | Won |

| Best Actress | Charlotte Gainsbourg | Won | |

| Best Actor | Willem Dafoe | Won | |

| Best Director of Photography | Anthony Dod Mantle | Won | |

| Special Bodil | Kristian Eidnes Andersen | Won | |

| Robert Award | Best Cinematography | Anthony Dod Mantle | Won |

| Best Director | Lars von Trier | Won | |

| Best Editor | Anders Refn | Won | |

| Best Film | Lars von Trier | Won | |

| Best Screenplay | Lars von Trier | Won | |

| Best Sound | Kristian Eidnes Andersen | Won | |

| Best Special Effects | Peter Hjorth Ota Bares | Won | |

| Best Actor | Willem Dafoe | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Charlotte Gainsbourg | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Frauke Firl | Nominated | |

| Best Make-Up | Hue Lan Van Duc | Nominated | |

| Best Production Design | Karl Júlíusson | Nominated | |

| Nordic Council | Nordic Council's Film Prize | Lars von Trier | Won |

| European Film Awards | Best Cinematographer | Anthony Dod Mantle | Won |

| Best Actress | Charlotte Gainsbourg | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Lars von Trier | Nominated | |

| Sant Jordi Awards | Best Foreign Actress (Mejor Actriz Extranjera) | Charlotte Gainsbourg | Won |

| Zulu Awards | Best Film | Lars von Trier | Nominated |

Festivals

| Festival | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cannes Film Festival | Best Actress | Charlotte Gainsbourg | Won |

| Palme d'Or | Lars von Trier | Nominated | |

| Neuchâtel International Fantastic Film Festival | Titra Film Award | Lars von Trier | Won |

Cancelled video game

According to a June 2009 article in the Danish newspaper Politiken, a video game called Eden, based on the film, was in the works. It was to start where the film ended. "It will be a self-therapeutic journey into your own darkest fears, and will break the boundaries of what you can and can't do in video games," said video game director Morten Iversen.[75] As of 2011, Zentropa Games are out of business and Eden has been cancelled.[76]

References

- Zolkos 2016, p. 141.

- "ANTICHRIST (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- McCarthy, Todd (17 May 2009). "Antichrist". Variety. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- Rehlin, Gunnar (30 July 2008). "Von Trier's 'Antichrist' moves ahead - Financing complete on English-language film". Variety. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- "Antichrist (2009)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Knight, Chris (20 March 2014). "Nyphomaniac, Volumes I and II, reviewed: Lars von Trier's sexually graphic pairing will titillate, but fails to satisfy". National Post. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- Zolkos 2016, pp. 141–143.

- Zolkos 2016, p. 149.

- Zolkos 2016, p. 151.

- Zolkos 2016, pp. 145–146.

- Fanning, Evan (26 July 2009). "Antichrist was Lars' 'fun' way of treating depression". The Independent. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- Simmons 2015, p. 7.

- Simmons 2015, p. 9.

- Simmons 2015, p. 11.

- Sinnerbrink 2016, pp. 100–101.

- Sinnerbrink 2016, pp. 101–102.

- Dowell, Pat (6 November 2011). "Lars Von Trier: A Problematic Sort Of Ladies' Man?". NPR. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Macaulay, Scott (2009). "Civilization and its discontents". Filmmaker. Los Angeles, California: Independent Feature Project. 18 (Fall). ISSN 1063-8954. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- Goodsell, Luke (23 November 2009). "'I Don't Hate Women': Lars von Trier on Antichrist". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 29 November 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- Aftab, Kaleel (29 May 2009). "Lars von Trier - 'It's good that people boo’". The Independent. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- Vestergaard, Jesper (8 April 2005). "Lars von Trier dropper Antichrist". CinemaZone (in Danish). Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- Møller, Hans Jørgen (11 May 2007). "Von Trier: Jeg kan ikke lave flere film" (in Danish). Politiken. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Thorsen, Nils (17 May 2009). "Lars von Trier: Det hjemmelavede menneske" (in Danish). Politiken. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "Antichrist". Nationalfilmografien (in Danish). Danish Film Institute. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

- Ebert, Roger (19 May 2009). "Cannes #6: A devil's advocate for "Antichrist"". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010.

- Fyhn, Mikkel (23 May 2009). "Mød effektmændene bag Triers mareridt". Politiken (in Danish). Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "Samlejescene med masser af håndarbejde". AudioVisuelle Medier (in Danish). May 2009. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- Bo, Michael (23 May 2009). "De overlevede Antikrist - og von Trier". Politiken (in Danish). Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- Bourgeois, David (20 May 2009). "Antichrist's Willem Dafoe: 'We Summoned Something We Didn't Ask For'". Movieline. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- Crocker, Jonathan (22 July 2009). "RT Interview: Lars von Trier on Antichrist". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Gainsbourg, Charlotte (2010). Charlotte etc. Antichrist (Blu-ray, Interview). The Criterion Collection. ASIN B003KGBISO.

- Römer-Westarp, Petra (8 September 2009). "Antichrist:Früher Einsatz im finstren Wald". Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger (in German). Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Lars von Trier dreht Antichrist in NRW – Ein Settermin" Archived May 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (in German). Filmstiftung Nordrhein-Westfalen. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- Unlisted author (2 June 2009). "Efekty specjalne w Antychryście" Archived June 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (in Polish). Platige Image Community. Retrieved on 18 June 2009.

- Antichrist Pressbook Archived January 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Artificial Eye. Retrieved on 2011-10-30.

- Haynes 2007, p. 25.

- Hoberman, J. (26 March 2014). "Sex: The Terror and the Boredom". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- "Festival de Cannes: Antichrist". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- "Lars von Trier film 'Antichrist' shocks Cannes". reuters.com. 17 May 2009. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- Zolkos 2016, pp. 142–143.

- Johnston, Sheila (22 July 2009). "Is Antichrist anti-women?". The Independent. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- Roxborough, Scott (18 May 2009). "Lars von Trier speared over 'Antichrist’". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- "Cannes jury gives its heart to works of graphic darkness". Irish Times. 25 May 2009.

- "Pixar pooch picks Up Cannes prize". BBC Online. 22 May 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- "Lars von Trier agrees to cut his 'Antichrist' to avoid censorship". France 24. Associated French Press. 23 May 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Pham, Annika (22 May 2009). "Antichrist sold to UK and US". Cineuropa. Retrieved on 26 May 2009.

- Sharkey, Betsy (23 October 2009). "'Antichrist'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- McNary, Dave (24 June 2009). "'Antichrist' gets pre-Halloween date". Variety. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- Phillips, Michael (26 October 2009). "Dafoe leaps into the taboo in 'Antichrist'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- Larn, Paul (12 June 2009). "Cannes Sensation ANTICHRIST to Be Uncut in the UK". The Cinema Post. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Nikkah, Roya (21 June 2009). "Controversial Antichrist film with uncut scenes of torture and pornography". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- Sweney, Mark (4 November 2009). "Antichrist sex ads escape ban". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- Lee, Bejamin (3 February 2016). "Lars von Trier's Antichrist banned in France seven years after release". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Horror Movies: Banned, Pulled and X-Rated Part II". Horror Freak News. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Fiil-Jensen, Lars (26 May 2009). "Publikum vil se 'Antichrist’" (in Danish). FILMupdate. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Nordisk Film & TV Fond: Antichrist Wins Award and Danish Audiences Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Skotte, Kim (17 May 2009). "'Antichrist' er et grotesk mesterstykke". Politiken (in Danish). Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Iversen, Ebbe (18 May 2009). "Fire stjerner til »Antichrist«" (in Danish). Berlingske Tidende. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Lindberg, Kristian (24 May 2009). "Danske anmeldere beskyldes for rygklapperi". Berlingske Tidende (in Danish). Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- Monggaard, Christian (21 December 2009). "Hvad skulle vi gøre uden "Paprika Steen og Lars von Trier?". Dagbladet Information (in Danish). Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- "Von Trier's 'Antichrist' wins Nordic film award". The Independent. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- Vallentin, Joanna (7 February 2010). "'Antichrist' årets bedste film". Berlingske Tidende (in Danish). Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- "Antichrist". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- "Antichrist (2009)". Metacritic. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- Ebert, Roger (21 October 2009). "Antichrist". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved on 18 July 2012.

- Dudek, Duane (28 January 2010). "Antichrist". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved on 18 July 2012.

- Smith, Martin Ian (13 January 2015). "Revulsion and Derision: Antichrist, The Human Centipede II and the British Press". Film International. Retrieved on 30 April 2010.

- "Empire's Antichrist Movie Review". Empire.

- Davies, Luke. Tooth and Claw: Lars von Trier's 'Antichrist'. The Monthly. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- Waters, John. Tooth Film: Best of 2009. Artforum. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Meza, Ed (12 December 2009). "'White Ribbon' is a fav at European Film Awards". Variety. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films: Who voted?". BBC. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- Boland, Michaela (14 January 2010). "Industry alarm at R-rated cover-up". The Australian. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Lanthier, Joseph Jon (9 November 2010). "Antichrist". Slant Magazine. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Vigild, Thomas (17 June 2009). "'Antichrist' fortsætter - som spil" (in Danish). Politiken. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- Rick, Christopher. "Zentropa Games Calls It Quits in Denmark" Archived 27 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

Works cited

- Haynes, Bruce (2009). The End of Early Music: A Period Performer's History of Music for the Twenty-First Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518987-6.

- Simmons, Amy (2015). Antichrist. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-993-07171-3.

- Sinnerbrink, Robert (2016). "Provocation and perversity: Lars von Trier's cinematic anti-philosophy". In Jeong, Seung-hoon; Szaniawski, Jeremi (eds.). The Global Auteur: The Politics of Authorship in 21st Century Cinema. London: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 95–114. ISBN 978-1-501-31265-6.

- Zolkos, Magdalena (2016). "Violent affects: Nature and the feminine in Antichrist". In Butler, Rex; Denny, David (eds.). Lars von Trier's Women. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 141–158. ISBN 978-1-501-32245-7.

External links

- Antichrist at IMDb

- Antichrist at Box Office Mojo

- Antichrist at Rotten Tomatoes

- Antichrist at Metacritic

- Antichrist at the Swedish Film Institute Database

- IFC.com interview with Lars von Trier

- Essay: On Lars von Trier's Antichrist

- All Those Things That Are to Die: Antichrist an essay by Ian Christie at the Criterion Collection

- Essay Revulsion and Derision: Antichrist, The Human Centipede II and the British Press by Martin Ian Smith at Film International

- The first episode of Brows Held High focusing on LVT's Antichrist on YouTube