Armed priests

Throughout history, armed priests or soldier priests have been recorded. Distinguished from military chaplains who served the military or civilians as spiritual guidance (non-combatants), these priests took up arms and fought in conflicts (combatants). The term warrior priests is usually used for armed priests of the antiquity and Middle Ages, and of historical tribes.

History

In Greek mythology, the Curetes were identified as armed priests.[1] In Ancient Rome, the Salii who were armed priests carried sacred shields through the city during the March festivals.[2] Livy (59 BC–17 AD) mentions armati sacerdotes (armed priests).[3]

Medieval European canon law said that a priest could not be a soldier, and vice versa. Priests were allowed on the battlefield as chaplains, and could only defend themselves with clubs.[4]

The Aztecs had a vanguard of warrior priests who carried deity banners and made sacrifices on the battlefield.[5] A Cherokee priest who killed during battle received the title of Nu no hi ta hi.[6]

The warrior-priest was a common figure in the First Serbian Uprising (1804–13).[7] Several archpriests and priests were commanders in the uprising.[8] Serbian Orthodox monasteries sent monks to join the ranks of the Serbian Army.[7]

Legacy

The "Pyrrhic" dance in Crete is said to have been the ritual dance of armed priests.[9]

Notable groups

- Chivalric military orders, Christian religious societies of knights of the Catholic Church in feudal Europe such as the Knights Templar, the Knights Hospitaller, the Teutonic Knights and many others.

- Shaolin Monk, Chen, Zen Buddhist monks in feudal China

- Righteous armies , Korean guerilla fighters, including monks, who resisted the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98).

- Sant Sipahi is a Sikh ideology, inspired by the lives of Sikh gurus, of a saint soldier who would adhere one's life in strict discipline both in mind and body.

- Naga Sadhus, a militaristic sect of arms-bearing Hindu sannyasi.

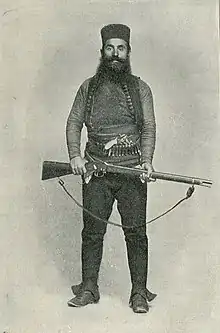

Notable people

- Eastern Orthodoxy

- Luka Lazarević (1774–1852), Serbian Orthodox priest, vojvoda (general) of the Serbian Revolution.[11]

- Matija Nenadović (1777–1854), Serbian Orthodox archpriest, commander in the Serbian Revolution.[12]

- Athanasios Diakos (1788–1821), Greek Orthodox priest, commander in the Greek War of Independence.

- Mićo Ljubibratić (1839–1889), Serbian Orthodox priest, fought in the Herzegovina Uprising.[13]

- Bogdan Zimonjić (1813–1909), Serbian Orthodox priest, active during the 1852–62 and 1875–78 uprisings in Herzegovina

- Vukajlo Božović, Serbian Orthodox archpriest, fought in the Balkan Wars.[14]

- Jovan Grković-Gapon (1879–1912), Serbian Orthodox priest, guerrilla in Macedonia.

- Tasa Konević, Serbian Orthodox priest, guerrilla in Macedonia.

- Mihailo Dožić (1848–1914), Serbian Orthodox priest, guerrilla in Potarje (1875–78).

- Stevan Dimitrijević (1866–1953), Serbian Orthodox priest, guerrilla in Macedonia (fl. 1904).

- Momčilo Đujić (1907–1999), Serbian Orthodox priest, World War II Chetnik.

- Vlada Zečević (1903–1970), Serbian Orthodox priest, Yugoslav Partisan.

- Catholicism

- Archbishop Turpin (d. 800), legendary (insofar as military accomplishments) member of Charlemagne's Twelve Peers.

- Rudolf of Zähringen (1135–1191), Catholic bishop, Crusader.

- Joscius (d. 1202), Catholic archbishop, Crusader.

- Reginald of Bar (fl. 1182–1216), Catholic bishop, Crusader.

- Aubrey of Reims (fl. 1207–18), Catholic archbishop, Crusader.

- Arnaud Amalric (d. 1225), Cistercian abbott, Crusader.

- Bernardino de Escalante (1537–after 1605), Catholic priest

- José Félix Aldao (1785–1845), Dominican friar, General in the Argentine War.

- Cresconius, (c. 1036–1066), Bishop of Iria, Spanish bishop who fought Vikings raiders

- José María Morelos (1765–1815), Roman Catholic priest, Mexican independentist commander.

- Camilo Torres Restrepo (1929-1966), Colombian socialist guerrilla and Catholic priest

- Gaspar García Laviana (1941-1978), Catholic priest inspired by Liberation theology to join the Sandanista revolution as a guerrilla soldier

- Odo of Bayeux (d. 1097), Bishop of Bayeux, half-brother of William the Conqueror

- Stanisław Brzóska (1832-1865), Polish Catholic priest, head chaplain and one of the generals in January Uprising

- John Murphy (priest) (1753 – c. 2 July 1798), Irish Catholic priest and one of the leaders of the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Captured, tortured and executed by British Crown forces.

- Anglicanism

- Leonidas Polk (1806-1864), Confederate General, United States Military Academy graduate, Episcopal bishop of Louisiana

- Other

- The tlatoani, ruler of Nahuatl pre-Hispanic states, were high priests and military commanders.

- Dutty Boukman (d. 1791), voodoo priest and Haitian Revolution leader.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Armed priests. |

References

- Jürgen Trabant (2004). Vico's New Science of Ancient Signs: A Study of Sematology. Psychology Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-415-30987-5.

- Cyril Bailey (1932). Phases in the Religion of Ancient Rome. University of California Press. pp. 69–. GGKEY:RFYRJLHJJDQ.

- Roger D. Woodard (28 January 2013). Myth, Ritual, and the Warrior in Roman and Indo-European Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–. ISBN 978-1-107-02240-9.

- John Howard Yoder; Theodore J. Koontz; Andy Alexis-Baker (1 April 2009). Christian Attitudes to War, Peace, and Revolution. Brazos Press. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-1-58743-231-6.

- Manuel Aguilar-Moreno (2007). Handbook to Life in the Aztec World. Oxford University Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-0-19-533083-0.

- Thomas E. Mails (1992). The Cherokee People: The Story of the Cherokees from Earliest Origins to Contemporary Times. Council Oak Books. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-0-933031-45-6.

- Király & Rothenberg 1982, p. 275.

- Király & Rothenberg 1982, pp. 273–275.

- The Origin of Attic Comedy. CUP Archive. 1934. pp. 65–.

- Hitomi Tonomura (1 January 1992). Community and Commerce in Late Medieval Japan: Corporate Villages of Tokuchin-ho. Stanford University Press. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-0-8047-6614-2.

- Király & Rothenberg 1982, p. 273.

- Király & Rothenberg 1982, p. 274.

- Srejović, Gavrilović & Ćirković 1983.

- Srejović, Gavrilović & Ćirković 1983, p. 321.

Sources

- Srejović, Dragoslav; Gavrilović, Slavko; Ćirković, Sima M. (1983). Istorija srpskog naroda: knj. Od Berlinskog kongresa do Ujedinjenja 1878-1918. Srpska književna zadruga.

- Király, Béla K.; Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1982). War and Society in East Central Europe: The first Serbian uprising 1804-1813. Brooklyn College Press. ISBN 978-0-930888-15-2.