First Serbian Uprising

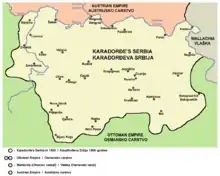

The First Serbian Uprising (Serbian: Први српски устанак / Prvi srpski ustanak, Turkish: Birinci Sırp Ayaklanması) was an uprising of Serbs in the Sanjak of Smederevo against the Ottoman Empire from 14 February 1804 to 7 October 1813. Initially a local revolt against renegade janissaries who had seized power through a coup, it evolved into a war for independence (the Serbian Revolution) after more than three centuries of Ottoman rule and short-lasting Austrian occupations.

| First Serbian Uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Serbian Revolution | |||||||

The Conquest of Belgrade by Katarina Ivanović | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Around 40,000 soldiers | Over 150,000 soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Around 11,000 soldiers killed | Unknown | ||||||

The janissary commanders murdered the Ottoman Vizier in 1801 and occupied the sanjak, ruling it independently from the Ottoman Sultan. Tyranny ensued; the janissaries suspended the rights granted to Serbs by the Sultan earlier, increased taxes, and imposed forced labor, among other things. In 1804 the janissaries feared that the Sultan would use the Serbs against them, so they murdered many Serbian chiefs. Enraged, an assembly chose Karađorđe as leader of the uprising, and the rebel army quickly defeated and took over towns throughout the sanjak, technically fighting for the Sultan. The Sultan, fearing their power, ordered all pashaliks in the region to crush them. The Serbs marched against the Ottomans and, after major victories in 1805–06, established a government and parliament that returned the land to the people, abolished forced labor, and reduced taxes.

Military success continued over the years; however, there was dissent between Karađorđe and other leaders—Karađorđe wanted absolute power while his dukes, some of whom abused their privileges for personal gain, wanted to limit it. After the Russo-Turkish War ended and Russian support ceased, the Ottoman Empire exploited these circumstances and reconquered Serbia in 1813.

Although the uprising was crushed, it resumed shortly with the Second Serbian Uprising in 1815

Background

Belgrade was made the seat of the Pashalik of Belgrade (also known as the Sanjak of Smederevo), and quickly became the second largest Ottoman town in Europe at over 100,000 people, surpassed only by Constantinople.[1]

In 1788, during the Austro-Turkish War (1788–1791), Koča's frontier rebellion saw eastern Šumadija occupied by Austrian Serbian Free Corps and hajduks, and subsequently most of the Sanjak of Smederevo was occupied by the Habsburg Monarchy (1788–91). From 15 September to 8 October 1789, a Habsburg Austrian force besieged the fortress of Belgrade. The Austrians held the city until 1791, when it handed Belgrade back to the Ottomans according to the terms of the Treaty of Sistova.

With the return of the sanjak to the Ottoman Empire the Serbs expected reprisals from the Turks due to their support of the Austrians. Sultan Selim III had given complete command of the Sanjak of Smederevo and Belgrade to battle-hardened Janissaries that had fought Christian forces during the Austro-Turkish War and many other conflicts. Although Selim III granted authority to the peaceful Hadži Mustafa Pasha (1793), tensions between the Serbs and the Janissary command did not subside.[2]

In 1793 and 1796 Selim III proclaimed firmans, which gave more rights to Serbs. Among other things, taxes were to be collected by the obor-knez (dukes); freedom of trade and religion were granted and there was peace. Selim III also decreed that some unpopular janissaries were to leave the "Belgrade Pashalik", as he saw them a threat to the central authority of Hadži Mustafa Pasha. Many of those janissaries were employed by or found refuge with Osman Pazvantoğlu, a renegade opponent of Selim III in the Sanjak of Vidin. Fearing the dissolution of the Janissary command in the Sanjak of Smederevo, Osman Pazvantoğlu launched a series of raids against Serbians without the permission of the Sultan, causing much instability and fear in the region.[3] Pazvantoğlu was defeated in 1793 by the Serbs at the Battle of Kolari.[4] In the summer of 1797 the sultan appointed Mustafa Pasha to the position of beglerbeg of Rumelia Eyalet and he left Serbia for Plovdiv to fight against the Vidin rebels of Pazvantoğlu. During the absence of Mustafa Pasha, the forces of Pazvantoğlu captured Požarevac and besieged the Belgrade fortress.[5] At the end of November 1797 obor-knezes Aleksa Nenadović, Ilija Birčanin and Nikola Grbović from Valjevo brought their forces to Belgrade and forced the besieging janissary forces to retreat to Smederevo.[6][5]

However, on January 30, 1799, Selim III allowed the Janissaries to return, referring to them as local Muslims from the Sanjak of Smederevo. Initially the Janissaries accepted the authority of Hadži Mustafa Pasha, until a Janissary in Šabac, named Bego Novljanin, demanded from a Serb a surcharge and murdered the man when he refused to pay. Fearing the worst, Hadži Mustafa Pasha marched on Šabac with a force of 600 to ensure that the Janissary was brought to justice and order was restored. Not only did the other Janissaries decided to support Bego Novljanin but Osman Pazvantoğlu attacked the Belgrade Pasahaluk in support of the Janissaries.[7]

On 15 December 1801 Vizier Hadži Mustafa Pasha of Belgrade was killed by Kučuk-Alija, one of the four leading dahije.[8]

This resulted in the Sanjak of Smederevo being ruled by these renegade janissaries independently from the Ottoman government, in defiance of the Sultan.[9] The janissaries imposed "a system of arbitrary abuse that was unmatched by anything similar in the entire history of Ottoman misrule in the Balkans".[10] The leaders divided the sanjak into pashaliks.[10] They immediately suspended Serbian autonomy and drastically increased taxes, land was seized, forced labor (čitlučenje) was introduced and many Serbs fled to the mountains.[11]

The tyranny endured by the Serbs caused them to send a petition to the Sultan, which the dahije learned of.[12] The dahije were concerned that the Sultan would make use of the Serbs to oust them. To forestall this they decided to execute leading Serbs throughout the sanjak, in an event known as the "Slaughter of the Knezes", which took place in late January 1804.[9] According to contemporary sources from Valjevo, the severed heads of the leaders were put on public display in the central square to serve as an example to those who might plot against the rule of the dahije.[9] This enraged the Serbs, who led their families into the woods and started murdering the subaşi (village overseers).[10]

Uprising against the Dahije

.jpg.webp)

Following the Slaughter of the Knezes and building on the resentment towards the dahije who had rolled back privileges granted to the Serbs by Selim II, on 14 February 1804, in the small village of Orašac near Aranđelovac, leading Serbs gathered and decided to begin an uprising against the dahijas. Among those present were Stanoje Glavaš, Atanasije Antonijević, Tanasko Rajić and other prominent local leaders. The Serb Chieftains gathered in Orašac and elected Đorđe Petrović, a livestock merchant known as Karađorđe, as their leader. Karađorđe had fought as a member of the Freicorps during the Austro-Turkish war, had been an officer in the national militia, and thus had considerable military experience.[13] The Serbian forces quickly assumed control of Šumadija, reducing dahija control to just Belgrade. The government in Istanbul instructed the pashas of the neighboring pashaliks not to assist the dahijas.[14] The Serbs, at first technically fighting on the behalf of the Sultan against the janissaries, were encouraged and aided by a certain Ottoman official and the sipahi (cavalry corps).[15] For their small numbers, the Serbs had great military successes, having taken Požarevac, Šabac and charged Smederevo and Belgrade, in quick succession.[15]

The Sultan, who feared that the Serb movement might get out of hand, sent the former pasha of Belgrade, and now Vizier of Bosnia, Bekir Pasha, to officially assist the Serbs, but in reality to keep them under control.[15] Alija Gušanac, the janissary commander of Belgrade, faced by both Serbs and Imperial authority, decided to let Bekir Pasha into the city in July 1804.[15] The dahije had previously fled east to Ada Kale, an island on the Danube.[16] Bekir ordered the surrender of the dahije; meanwhile, Karađorđe sent his commander, Milenko Stojković, to the island.[17] The dahije refused to surrender, upon which Stojković attacked and captured them, then had them beheaded, on the night of 5–6 August 1804.[17] After crushing the power of the dahijas, Bekir Pasha wanted the Serbs to be disbanded; however, since the janissaries still held important towns such as Užice, the Serbs were unwilling to halt without guarantees.[16] In May 1804, Serbian leaders under Dorđe Petrović met in Ostružnica to continue the uprising. Their goals were to seek the protection of Austria, to petition Sultan Selim III for greater autonomy, and to petition the Russian ambassador in Istanbul for Russian protection as well. Because of the recent Russo-Turkish friendship in light of France's expanding influence, the Russian government until summer 1804 had a neutral policy toward the Serbian revolt. Indeed, at the beginning of the uprising when petitioned for aid in Montenegro, the Russian emissary to Cetinje declined to relay the message, instructing the Serbs to petition the Sultan. However, in summer 1804 following the Ostružnica assembly, the Russian government switched courses with the goal of having Istanbul recognize it as the guarantor of peace in the region.[14]

Negotiations between the Serbs and the Ottomans were mediated by the Austrian governor of Slavonia, and also began in May 1804. The Serbs demanded putting the Belgrade pashalik under the control of a Serbian knez, and giving him the power to collect taxes to be paid to Istanbul, along with further restrictions on janissaries. In 1805, negotiations broke down: the Porte could not accept a foreign power-guaranteed agreement, and the Serbs refused to lay down their arms. Fearing a Christian uprising, the Porte issued a decree to disarm on 7 May 1805 asking the rebels to rely on regular Ottoman troops to protect them from the dahijas, the decree was summarily ignored by the Serbs.[18][16] Sultan Selim III ordered the pasha of Niš, Hafiz Pasha, to march against the Serbs and take over Belgrade.[19]

Uprising against the Ottomans

The first major battle was the Battle of Ivankovac in 1805, in which the Serbs defeated for the first time, not a rebel Muslim force but the Sultan's army forcing it to retreat toward Niš. In November the fortress of Smederevo fell making it the capital of the rebellion.[13]

The second major battle of the uprising was the Battle of Mišar in 1806, in which the rebels defeated an Ottoman army from the Eyalet of Bosnia led by the Turkish Sipahi Suleiman-Pasa. At the same time the rebels, led by Petar Dobrnjac, defeated Osman Pazvantoğlu and another Ottoman army sent from the southeast at Deligrad. The Ottomans were consistently defeated despite their repeated efforts and the support of Ottoman commanders led by Ibrahim Bushati and Ali Pasha's two sons, Muktar Pasha and Veli Pasha. In December 1806 the rebels captured Belgrade thus taking control of the entire pashalik. The insurgents then sent Belgrade merchant Petar Ičko as their envoy to the Ottoman government in Constantinople. He managed to obtain for them a favourable treaty named after him the Ičko's Peace.[20] The Turks agreed to some measure of Serbian autonomy However the Serbian leaders rejected the treaty and possibly poisoned Ičko due to his dealings with the Ottomans.

In 1805 the Serbian rebels organized a basic government for administering the lands under Serbian control. The rule was divided among the Narodna Skupština (People's Assembly), the Praviteljstvujušči Sovjet (Ruling Council) and Karađorđe himself. The Ruling Council was established by recommendation of the Russian Minister for Foreign Affairs Chartorisky and on the proposal of some of the dukes (Jakov and Matija Nenadović, Milan Obrenović, Sima Marković),[21] in order to keep a check on Karađorđe's powers. The idea of Boža Grujović, the first secretary, and Matija Nenadović, the first president, was that the council would become the government of the new Serbian state.[22] It had to organize and supervise the administration, the economy, army supply, order and peace, judiciary, and foreign policy.[22] The land was returned, forced labour was abolished and taxes were reduced. Apart from dispensing with a poll tax on non-Muslims (jizya), the revolutionaries also abolished all feudal obligations in 1806, the emancipation of peasants and serfs representing a major social break with the past.

The Battle of Deligrad in December 1806 provided a decisive victory for the Serbs and bolstered the morale of the outnumbered rebels. To avoid total defeat, Ibrahim Pasha negotiated a six-week truce with Karađorđe. By 1807 the demands for self-government within the Ottoman Empire evolved into a war for independence backed by the military support of the Russian Empire. Combining patriarchal peasant democracy with modern national goals, the Serbian revolution was attracting thousands of volunteers among Serbs from across the Balkans and Central Europe. The Serbian Revolution ultimately became a symbol of the nation-building process in the Balkans, provoking unrest among the Christians in both Greece and Bulgaria. Following a successful siege with 25,000 men in late 1806, on 8 January 1807 Karađorđe proclaimed Belgrade the capital of Serbia after the remaining fortifications surrounded on St Stephen's day.[23]

Past rebellions had been put down by the Ottoman Turks with much bloodshed and repression.[24] In February 1804 the janissaries had beheaded seventy-two Serbs and stacking their heads on top of the citadel of Belgrade. Those actions generated equally bloody revenge now that the tables were turned.[25] After the liberation of Belgrade a massacre of Turks took place.[26] Serb historian Stojan Novakovic described the event as a "thorough cleansing of the Turks".[27] According to Archbishop Leontii, after the Serbs finally stormed the fortress of Belgrade, the commandant was killed "as well as all other Muslim inhabitants" and Turkish women and children were baptized.[28][29] The slaughter was accompanied by widespread destruction of Turkish and Muslim property and mosques.[30] A substantial part of those killed were not of actual Turkish ancestry, but local Slavs who had converted to Islam throughout the centuries. The massacre sparked a debate within the rebel faction. The older generation of rebels considered the massacre to be a sin, but the dominant principle was that all Muslims had to be removed.[31]

In 1808 Selim III was executed by Mustafa IV, who was subsequently deposed by Mahmud II. In the midst of this political crisis, the Ottomans were willing to offer the Serbs a wide autonomy: however, the discussions led to no agreement between the two, as they could not agree on the exact boundaries of Serbia.[32]

The Proclamation (1809) by Karađorđe in the capital of Belgrade probably represented the apex of the first phase. It called for national unity, drawing on Serbian history to demand freedom of religion and formal, written rule of law, both of which the Ottoman Empire had failed to provide. It called on Serbs to stop paying taxes to the Porte, deemed unfair as based on religious affiliation. Karađorđe now declared himself hereditary supreme leader of Serbia, although he agreed to act in cooperation with the governing council, which was to also be the supreme court. When the Ottoman-Russian War broke out in 1809, he was prepared to support Russia; the cooperation was, however, ineffective. Karađorđe launched a successful offensive in Novi Pazar, but Serbian forces were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Čegar.[33]

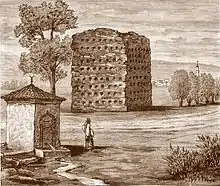

In March 1809 Hurşid Paşa was sent to the Sanjak of Smederevo to put down the revolt. The diverse Ottoman force included vast numbers of soldiers from many nearby Pashaliks (mostly from Albania and Bosnia) including servicemen such as Samson Cerfberr of Medelsheim, Osman Gradaščević and Reshiti Bushati. On 19 May 1809 3,000 rebels led by commander Stevan Sinđelić were attacked by a large Ottoman force on Čegar Hill, located close to the city of Niš.

Owing to a lack of coordination between commanders, the reinforcement of other detachments failed, although the numerically superior Ottomans lost thousands of troops in numerous attacks against the Serb positions. Eventually the rebels were overwhelmed and their positions were overrun; not wishing for his men to be captured and impaled, Sinđelić fired into his entrenchment's gun powder magazine resulting in an explosion that killed all the rebels and Ottoman troops in the vicinity. Afterward, Hurshid Pasha ordered that a tower be made from the skulls of Serbian revolutionaries—once complete, the ten-foot-high Skull Tower contained 952 Serbian skulls embedded on four sides in 14 rows.

In July 1810 Russian troops arrived in Serbia for the second time; on this occasion, though, some military cooperation followed—weapons, ammunition and medical supplies were sent, and Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov participated in the planning of joint actions. The Russian assistance gave hope for a Serb victory.[33]

In August 1809 an Ottoman army marched on Belgrade, prompting a mass exodus of people across the Danube, among them Russian agent Radofinikin.[32] Facing disaster, Karađorđe appealed to the Habsburgs and Napoleon, with no success.[32] At this point the Serb rebels were on the defensive, their aim being to hold the territories and not make further gains.[32][33] Russia, faced with a French invasion, wished to sign a definitive peace treaty, and acted against the interests of Serbia.[33] The Serbs were never informed of the negotiations; they learned the final terms from the Ottomans.[33] This second Russian withdrawal came at the height of Karađorđe's personal power and the rise of Serb expectations.[33] The negotiations that led to the Treaty of Bucharest (1812) contained Article 8, dealing with the Serbs; it was agreed that Serb fortifications were to be destroyed, unless of value to the Ottomans; pre-1804 Ottoman installations were to be reoccupied and garrisoned by Ottoman troops. In return, the Porte promised general amnesty and certain autonomous rights. The Serbs were to control "the administration of their own affairs" and the collection and delivery of a fixed tribute.[34] Reactions in Serbia were strong; the reoccupation of fortresses and cities was of particular concern and fearful reprisals were expected.[34]

Some of the leaders of the uprising later abused their privileges for personal gain. There was dissent between Karađorđe and other leaders; Karađorđe wanted absolute power, while his dukes wanted to limit it. After the Russo-Turkish War ended, and pressure of French invasion in 1812, the Russian Empire withdrew its support for the Serb rebels. The Ottoman Empire exploited these circumstances and reconquered Serbia in 1813 after Belgrade was retaken. The Ottoman forces burned down villages along main invading routes while their inhabitants were massacred or made refugees, with many women and children being enslaved. Karađorđe, along with other rebel leaders, fled to Habsburg provinces, Wallachia and Russia.[35]

Aftermath

As a clause of the treaty of Bucharest, the Ottomans agreed to grant general amnesty to the participants of the insurrection,[36] however as soon as Turkish rule was reimposed to Serbia, villages were burned and thousands were sent into slavery. Belgrade became a scene of brutal revenge, on 17 October 1813, in one day alone, 1,800 women and children were sold as slaves.[36]

Direct Ottoman rule also meant the abolition of all Serbian institutions. Tensions persisted and in 1814, Hadži Prodan, one of Karađorđe's former commanders, launched a new uprising, which failed. After a riot at a Turkish estate in 1814, the Ottoman authorities massacred the local population and publicly impaled 200 prisoners at Belgrade.[35]

By March 1815, the Serbs held several meetings and organised again for resistance, the Second Serbian Uprising started in April, led by Miloš Obrenović, it eventually succeeded in turning Serbia as a semiautonomous state.[37]

References

- "The History of Belgrade". Belgradenet.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- The Ottoman Empire and the Serb Uprising, S J Shaw in The First Serbian Uprising 1804–1813 Ed W Vucinich, p. 72

- Ranke 1847.

- Roger Viers Paxton (1968). Russia and the First Serbian Revolution: A Diplomatic and Political Study. The Initial Phase, 1804–1807, Stanford (1968). Department of History, Stanford University. p. 13.

- Ćorović 2001.

- Filipović, Stanoje R. (1982). Podrinsko-kolubarski region. RNIRO "Glas Podrinja". p. 60.

Ваљевски кнезови Алекса Ненадовић, Илија Бирчанин и Никола Грбовић довели су своју војску у Београд и учествовали у оштрој борби са јаничарима који су се побеђени повукли.

- Ranke 1847, p. 115.

- Ćorović 2001, ch. Почетак устанка у Србији.

- Ranke 1847, p. 119–120.

- Nicholas Moravcevich (2005). Selected essays on Serbian and Russian literatures and history. Stubovi kulture. pp. 217–218. ISBN 9788679791160.

- Reed, H.L. (2018). Serbia: A Sketch (in German). Outlook Verlag. p. 28. ISBN 978-3-7326-7904-1.

- Morison 2012, p. xvii.

- Jelavich et al. 1983, p. 200.

- Vucinich, Wayne S. The First Serbian Uprising, 1804–1813. Social Science Monographs, Brooklyn College Press, 1982.

- Morison 2012, p. xviii.

- Morison 2012, p. xix.

- Petrovich 1976, p. 34.

- Ursinus, M.O.H., “Ṣi̊rb”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 11 March 2018 <https://dx.doi.org.turing.library.northwestern.edu/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_1091%5B%5D> First published online: 2012

- Jelavich et al. 1983, p. 198.

- Petrovich 1976, p. 98-100.

- Janković 1955, p. 18.

- Čubrilović 1982, p. 65.

- Srđan Rudić et al. 2018, p. 299.

- Mojzes 2011, p. 10.

- Berend 2005, p. 123.

- Washburn, Dennis; Reinhart, Kevin (2007). Converting Cultures: Religion, Ideology and Transformations of Modernity. BRILL. p. 88. ISBN 9789047420330.

- Sudanow. Ministry of Culture and Information. 1994. p. 20.

- Berend, Ivan (2005). History Derailed: Central and Eastern Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century. University of California Press. p. 123. ISBN 0520245253.

- Vovchenko, Denis (2016). Containing Balkan Nationalism: Imperial Russia and Ottoman Christians, 1856-1914. Oxford University Press. p. 299. ISBN 9780190276676. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Lebel, G'eni (2007). Until "the Final Solution": The Jews in Belgrade 1521 - 1942. Avotaynu. p. 70. ISBN 9781886223332. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Aleksov, Bojan (2007). Washburn, Dennis; Reinhart, Kevin (eds.). Converting Cultures: Religion, Ideology, and Transformations of Modernity. BRILL. p. 88. ISBN 978-9004158221.

- Jelavich 1983, p. 201.

- Jelavich & Jelavich 1977, p. 34.

- Jelavich & Jelavich 1977, p. 35.

- http://staff.lib.msu.edu/sowards/balkan/lecture5.html

- Judah 1997, p. 188.

- Judah 1997, p. 189.

Sources

- Ćorović, Vladimir (2003). Карађорђе и први српски устанак. Свет књиге. ISBN 978-86-7396-057-9.

- Ćorović, Vladimir (2001) [1997]. Историја српског народа (in Serbian). Belgrade: Јанус.

- Čubrilović, Vasa (1982). Istorija političke misli u Srbiji XIX veka. Narodna knjiga.

- Damnjanović, Nebojša; Merenik, Vladimir (2004). The first Serbian uprising and the restoration of the Serbian state. Historical Museum of Serbia, Gallery of the Serbian Academy of Science and Arts.

- Gavrilović, Andra (1904). "Crte iz istorije oslobodjenja Srbije". (Public Domain)

- Jančikin, Jovan (1996). Први српски устанак у народној књижевности. Српски демократски савез у Мађарској. ISBN 9789638197061.

- Janković, Dragoslav (1955). Istorija države i prava Srbije u XIX veku. Nolit.

- Janković, Dragoslav (1981). Први српски устанак. Коларчев народни универзитет.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27458-6.

- Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (1977). The Establishment of the Balkan National States: 1804-1920. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80360-9.

- Kállay, Béni (1910). "Die Geschichte des serbischen Aufstandes, 1807-1810". (Public Domain)

- Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović (1947). Први и Други српски устанак. [With a Portrait.].

- Kovačević, Božidar (1949). Први српски устанак. Ново поколење.

- Morison, W. A. (2012) [1942]. The Revolt of the Serbs Against the Turks: (1804–1813). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-67606-0.

- Novaković, Stojan (1906). "Tursko carstvo pred srpski ustanak, 1780-1804". (Public Domain)

- Petrovich, Michael Boro (1976). A history of modern Serbia, 1804–1918. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Ranke, Leopold von (1847). History of Servia, and the Servian Revolution. J. Murray. (Public Domain)

- Stojančević, Vladimir (1994). Prvi srpski ustanak: Ogledi i studije. Vojna knj.

- Stojančević, Vladimir (2004). Srbija i srpski narod u vreme prvog ustanka. Matica srpska. ISBN 9788683651412.

- Vujnović, Andrej (2004). Први српски устанак и обнова српске државе. Галерија српске академије наука и уметности. ISBN 978-86-82925-10-1.

- Judah, T. (1997). The Serbs: History, Myth, and the Destruction of Yugoslavia. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07113-9.

- Srđan Rudić, S.A.; Belgrade 1521-1867, D.; The Institute of History, B.; Yunus Emre Enstitüsü, T.C.C.B.; Ćosović, T. (2018). Belgrade 1521-1867. Collection of Works / The Institute of History, Belgrade. Institute of History Belgrade. ISBN 978-86-7743-132-7.

- Jelavich, B.; Cambridge University Press; Joint Committee of Eastern Europe; Joint Committee on Eastern Europe (1983). History of the Balkans: Volume 1. Cambridge paperback library. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27458-6.

- Petrovich, M.B. (1976). A History of Modern Serbia, 1804-1918. A History of Modern Serbia, 1804-1918. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-140950-1.

- Berend, I.T. (2005). History Derailed: Central and Eastern Europe in the Long Nineteenth Century. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24525-9.

- Mojzes, P. (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-0663-2.

Further reading

- Bataković, Dušan T. (2006). "A Balkan-Style French Revolution? The 1804 Serbian Uprising in European Perspective" (PDF). Balcanica. SANU. XXXVI.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Đorđević, M. R. (1967). Oslobodilački rat srpskih ustanika 1804–1806. Belgrad: Vojnoizdavački zavod.

- Gavrilović, S. (1985) Građa bečkih arhiva o Prvom srpskom ustanku 1804–1810. Beograd: SANU, knj. I, 55

- Hrabak, Bogumil (1994). "Srpski ustanici i Novopazarski sandžak (Raška) 1804–1813. godine". Istorijski časopis. XL–XLI: 9–.

- Hrabak, Bogumil (1996). "Kosovo and Metohia and the First rebellion of the Serbs" (PDF). Baština (7): 151–168.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1935). "Spisi bečkih arhiva o Prvom srpskom ustanku: 1804". Zbornik. Belgrade. VIII.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1936). "Spisi bečkih arhiva o Prvom srpskom ustanku: 1805". Zbornik. Belgrade. X.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1937). "Spisi bečkih arhiva o Prvom srpskom ustanku: 1806". Zbornik. Belgrade.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1938). "Spisi bečkih arhiva o Prvom srpskom ustanku: 1807". Zbornik. Belgrade.

- Janjić, Jovan (2014). "The role of the clergy in the creation and work of the state authorities during the first Serbian uprising: Part one". Zbornik Matice Srpske Za Drustvene Nauke (149): 901–927. doi:10.2298/ZMSDN1449901J.

- Maticki, Miodrag (2004). Читанка Првог српског устанка. Belgrade: Чигоја Штампа.

- Meriage, Lawrence P. (1978). "The First Serbian Uprising (1804-1813) and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of the Eastern Question". Slavic Review. 37 (3): 421–439. doi:10.2307/2497684. JSTOR 2497684.

- Mikavica, Dejan (2009). "Уставно питање у Карађорђевој Србији 1804—1813". Истраживања. 20.

- Novaković, Stojan (1907). Уставно питање и закони Карађорђева времена: студија о постању и развићу врховне и среднишње власти у Србији, 1805–1811. Штампарија "Љуб. М. Давидовић".

- Nedeljković, Mile (2002). Voždove vojvode: broj i sudbina vojskovođa u Prvom srpskom ustanku. Fond Prvi srpski ustanak. ISBN 978-86-83929-02-3.

- Novaković, Stojan (1892). "Šest službenih pisama prvog ustanka 1806-1812. iz nekadašnje arhive vojvode Antonija Pljakića". Spomenik Srpske Kraljevske Akademije. Belgrade. XVII: 7–.

- Paxton, Roger Viers (1972). "Nationalism and Revolution: A Reexamination of the Origins of the First Serbian Insurrection 1804–1807". East European Quarterly. 6 (3): 337–.

- Perović, R., ed. (1978). Prvi srpski ustanak – akta i pisma na srpskom jeziku, 1804–1808. Belgrade: Narodna knjiga.

- Popović, M. (1908). "Ustanak u Gornjem Ibru i po Kopaoniku od 1806. do 1813. godine". Godišnjica Nikole Čupića. XXVII: 232–235.

- Popović, M. (1954). Pričanje savremenika o Prvom srpskom ustanku. Belgrade.

- Protić, Kosta (1893). "Ratni događaji iz Prvog srpskog ustanka pod Karađorđem Petrovićem 1804–1813". Godišnjica Nikole Čupića. XIII: 77–269.

- Radosavljević, Nedeljko V.; Marinković, Mirjana O. (2012). "Једна османска наредба о војном уништењу Србије из 1807. године" [An Ottoman order on the military destruction of Serbia from 1807]. Истраживања. 23: 283–293.

- Radosavljević, Nedeljko V. (2010). "The Serbian Revolution and the Creation of the Modern State: The Beginning of Geopolitical Changes in the Balkan Peninsula in the 19th Century". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 171–178. ISBN 9783643106117.

- Radovanović, Petar (1852). Војне Срба с Турцима. Belgrade.

- Rajić, Suzana (2010). "Serbia – the Revival of the Nation-state, 1804–1829: From Turkish Provinces to Autonomous Principality". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 143–148. ISBN 9783643106117.

- Stojančević, Vladimir (1980). Srbija u vreme prvog ustanka: 1804–1813. Narodni muzej.

External links

- Serbian Thermopylae - Battle of Chokeshina 1804 (Serbian Revolution War)

- Battle of Mishar 1806 (Serbian Revolution War)

![]() Media related to First Serbian Uprising at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to First Serbian Uprising at Wikimedia Commons