Art of Urartu

The art of Urartu refers to a historical and regional type of art from Urartu (Ararat), the ancient state of Western Asia which existed in the period from the 13th to the 6th centuries BC in the Armenian Highland. The art of Urartu was strongly influenced by nearby Assyria, the most prominent state of that period in the region. It peaked around the 8th century BC but was mostly looted, scattered and destroyed with the fall of Urartu about a century later.[1][2]

Overview

Urartian art was heavily influenced by neighboring Assyria, and despite the obvious stylistic differences was long considered a branch of Assyrian art. Urartian art is characterized by 1) a style following its canon more rigorously than in other cultures of the Ancient East, 2) preference for ornaments rather than representational scenes of life, and 3) the practice of copying old examples instead of improving them.[3][4] As a result, the style of Urartian craftsmen remained unchanged for several centuries and was gradually simplified.[3] Urartian art was relatively poorly characterized until the 1950s, when major archeological work was started at the ancient Urartian cities Teishebaini and Erebuni and many Urartian cuneiform tables were deciphered.

Bronze statuettes

Although Urartian masters were capable of producing large bronze statue, not even fragments of any have been found so far. Literature mentions that Assyrians, while looting the city of Musasir, removed a bronze statue of King Argishti I weighing 60 talents (about 1,8 tons). Small bronze objects of art were exclusively made for the king's palace and are divided into three groups: throne decorations, ornaments on copper cauldrons and, rarely, statuettes of Urartian gods.

Throne decorations

Between 1877 and 1885, local treasure hunters sold a few small bronze fragments to several European museums. These fragments later turned out to be parts of one and the same Urartian king's throne. They were cast in bronze into a mold and then gilded by wrapping in thin gold sheets. The fragments are currently preserved in the British Museum, Hermitage, Louvre, Metropolitan Museum of Art and in private collections in Paris and Brussels.

|

|

|

|

|

| Bronze parts of one throne (Hermitage, Russia). The sketch of an item from the British Museum on the right reveals that these two items are identical. All figures have protrusions and hooks for horizontal or vertical attachment, as well as coded signs, probably identifying location on the throne. | ||||

Boiler decorations

Cauldron decorations are the best-preserved objects of Urartian bronze and therefore were used in the early 20th century to identify the Urartian style in art.[3] The decorated copper cauldrons were apparently used for ritual ceremonies. For example, the annals of the Assyrian king Sargon II mention a bronze vessel filled with wine being part of the sacrifice to the god Ḫaldi.

The bronze statuettes were cast separately and then attached to the cauldron. They include bull heads and winged deities, possibly the god Shivini and his wife Tushpuea.[3] The technique of casting bronze ornaments spread from Urartu to the neighboring countries, in particular to Phrygia, and then to Europe. Urartian cauldron ornaments have been found in Rhodes, Athens, Boeotia, Delphi, Olympia and in Etruscan tombs.[6][7][8] Some Urartian bronze figures were removed from the boilers and re-used by other nations to decorate new vessels.

Statuettes of gods

Only three bronze statuettes depicting Urartian deities have been preserved. One, possibly of the god Ḫaldi, is stored in the British Museum, and two others are in the National Museum of the History of Armenia (copy in the Erebuni Museum, Yerevan, see image).

Weapons

Helmets

Numerous Urartian helmets have been recovered, more than 20 alone during the excavations of Teishebaini. Royal ceremonial helmets did not differ in shape from simple combat helmets but contained engraved images.

Shields

A few decorative bronze Urartian shields have been found near Van (they are stored in the British Museum and Berlin museums) and 14 were excavated at Karmir Blur. They have diameters ranging between 70 and 100 cm and were not made for combat, as judged from the thinness of the metal and the character of the handles. All these shields contain concentric circles of lions and bulls which were designed so that no figure would appear upside down. The images were first stamped and then engraved with various instruments. The Assyrian king Sargon II described six golden Urartian shields, which were looted in Musasir, weighing 6.5 kg each. They have not been recovered thus far.

|

|

|

|

| Shield of Sarduri II. Cuneiform inscription on the edge reads: "Sarduri, son of Argishti dedicates this helmet to God Ḫaldi."[12] | Shield of Argishti I. Cuneiform inscription on the edge reads: "Argishti, son of Menua, dedicates this helmet to God Ḫaldi."[13] | ||

Quivers

Only three royal Urartian quivers are known, all found during the excavations of Teishebaini. They are made of bronze and contain images of Urartian warriors.

|

|

| Quiver owned by Sarduri II (Hermitage). | |

| |

| Top of the quiver of Sarduri II. | |

| Quiver owned by Argishti I.[9] |

Armor

Poorly preserved remains of Urartian mail of Argishti I were excavated at Teishebaini.[14] Entire (or parts of) wide bronze belts were found in Turkey (Altıntepe), Iran (Lake Urmia) and Armenia (Karmir Blur). The belts were about 1 meter long and 12 cm wide and were designed to protect archers.

Jewelry

Jewelry of Urartu had two gradations: ornaments made of precious metals and stones for the king and his family, and their simplified bronze versions used by the rich. Many jewelry items were also used as amulets.[15] Annals of the Assyrian king Sargon II mention vast amounts of Urartian jewelry items made of silver and gold which were taken from Musasir in 714 BC.[1] They are not preserved and some may have been melted by treasure hunters.[3] The two largest recovered jewelry items are shown below. They are the pectoral decoration excavated at the late Urartian capital Rusahinili and the cover of the cauldron found at Teishebaini. Smaller items include golden pins, earrings, a bracelet and a few medallions. Jewelry was worn in Urartu by both men and women. Women's jewelry usually portrayed the Urartian goddess Arubani, wife of Ḫaldi – the supreme god of Urartu. Also common are Mesopotamian motifs such as tree of life and winged sun. More accessible jewelry included bronze bracelets and earrings and carnelian beads.[15]

|

|

|

| Women's silver jewelry with the image of God Ḫaldi on the throne and his wife Arubani. Berlin Museum. | Silver cauldron cover with a full-blown pomegranate on top, inscribed as property of King Argishti I.[9] | Carnelian beads, purchased from treasure hunters near Van, Turkey.[5] |

|

|

|

| Silver medallions and golden earrings (damaged by fire during the assault on Teishebaini), found at Karmir Blur.[9] | ||

Pottery and stone art

Contrary to expectations, very few stone reliefs and sculptures were found during excavations,[16] although the reliefs of the Assyrian king Sargon II depicting the Urartian city of Musasir clearly show large statues.[1] Only a few minor remnants of stone reliefs were discovered in Turkey: the rest were likely destroyed after the fall of Urartu. However, pottery items were found in large numbers.[17]

|

|

|

| Remains of a relief depicting God Teisheba standing on a bull, found reused in the ruins of the medieval fortress of Adiljevaz/Adilcevaz (Van Museum, Turkey) | Two stone boxes found at Karmir Blur. The right one depicts griffins and a winged sun.[14] | |

|

|

|

| Left to right: rhyton found at Karmir Blur.[9] Rhyton shaped as the neck of an animal, found near the city of Van, stored in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul. Glazed ritual vessel featuring bulls.[14] | ||

Wood and bone

A few art items made of bone were found, mostly broken to parts, such as the bone combs excavated near Teishebaini. The only preserved example of wooden art of Urartu is the horse which was attached to some larger wooden item.[3]

|

|

|

|

|

| Left to right: candelabrum found at Rusahinili; the wooden inserts are modern, bone and bronze inserts are original.[5] A leg of the same chandelier. Two bone plates featuring gods; the plates were decorations for other items and were found at Rusahinili.[5] Wooden horse head found at Karmir Blur.[9] | ||||

Frescoes

Colored frescoes in rather good condition were found in the ruins of the Urartian fortress of Erebuni.[18] Unlike many other Urartian cities, Erebuni was not burnt but left without a fight and then abandoned; this helped preserve its murals.[19][20]

|

|

|

|

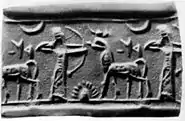

Cylinder seals

Urartu used cylinder seals similar to those from other ancient states of the Ancient Middle East. They depicted the moon, stars, religious images and sometimes hunting scenes.

|

|

|

Many features of Urartian art were preserved in the neighboring countries after the fall of Urartu in the 6th century BC. Observations by Boris Piotrovsky suggest that decoration and production techniques of Scythian belts and scabbards were borrowed from Urartu.[3] The Urartian way of decorating cauldrons spread over the ancient world, and it is believed that Armenian art and that of southern Georgia were partly based on the Urartian traditions.[20][22]

References

- Chahin, Mack, 148

- Urartu, Encyclopædia Britannica online

- Пиотровский Б. Б. Искусство Урарту VIII—VI вв. до н. э. ("The Art of Urartu, 8th–6th century BC"). (Hermitage, Leningrad, 1962

- Афанасьева В. К., Дьяконов И. М. (1968). Искусство Передней Азии 2 – середины 1 тысячелетия до н. э.. Памятники мирового искусства (The Art of Western Asia from 2nd to the middle of 1st millennium BC. Monuments of world art). Issue 2 (1st series). The Art of the Ancient Orient. Moscow: Искусство.

- Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey

- Pallottino, M. (1958). "Urartu, Greece and Etruria". East and West. Rome. 9 (1–2).

- Amandry P. Objets orientaux en Grèce et en Italie aux VIIIe et VIIe siècles avant Jésus-Christ, Syria, XXXV, 1 – 2, Paris 1958

- Maxwell, M., Hyslop KR Urartian Bronzes in Etruscan Tombs, Iraq, XVIII, 2, 1956

- National Museum of History of Armenia, Yerevan

- Пиотровский, Б. Б. Кармир-Блур II, Результаты раскопок 1949–1950 (Karmir Blur II, Results of Excavations 1949–1950), Academy of Sciences of Armenia, Yerevan, 1952

- Chahin, Mack, 156

- Пиотровский, Б. Б. Кармир-Блур III, Результаты раскопок 1951–1953 (Karmir Blur III, Results of Excavations 1951–1953), Academy of Sciences of Armenia, Yerevan, 1955

- Меликишвили, Г. А. Урартские клинообразные надписи (Urartian inscriptions), Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Moscow, 1960

- Erebuni Museum, Erevan, Armenia

- Есаян С. (2003). "Ювелирное искусство Урарту (Jewelry art of Urartu)". Историко-филологический журнал. Yerevan. 3.

- Марр Н. Я., Орбели И. А. Археологическая экспедиция 1916 года в Ван (Archaeological Expedition in 1916 to Van), Petrograd, 1922

- Chahin, Mack, 160

- Ходжаш С. И., Трухтанова Н. С., Оганесян К. Л. Эребуни. Памятник Урартского зодчества VIII—VI в. до н. э. (Erebuni. Monument of Urartu architecture of 8th–6th century BC), "Искусство", Moscow, 1979

- Оганесян К. Л. Арин-Берд I, Архитектура Эребуни по материалам раскопок 1950–1959 гг. (Arin-Bird I, Architecture of Erebuni from excavations during 1950–1959). Academy of Sciences of Armenia, Yerevan, 1961

- Пиотровский Б. Б. Ванское царство (Урарту) (kingdom of Van (Urartu)), Eastern Literature Publishing House, Moscow, 1959

- Аракелян Б.Н. Клад серебряных изделий из Эребуни (Silver treasures excavated at Erebuni) Soviet Archaeology, 1971, Vol. 1

- Степанян Н. Искусство Армении: черты историко-художественного развития Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine (The Art of Armenia: the features of historical and artistic development). Soviet Artist, Moscow, 1989, ISBN 5-269-00042-3

Bibliography

- Mack Chahin (21 December 2001). The kingdom of Armenia: a history. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1452-0.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urartian art. |

- Guitty Azarpay Urartian Art and Artifacts. A chronological study, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1968

- John Boardman (5 August 1982). The Prehistory of the Balkans and the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries B.C. Cambridge University Press. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-521-22496-3.