Assyria

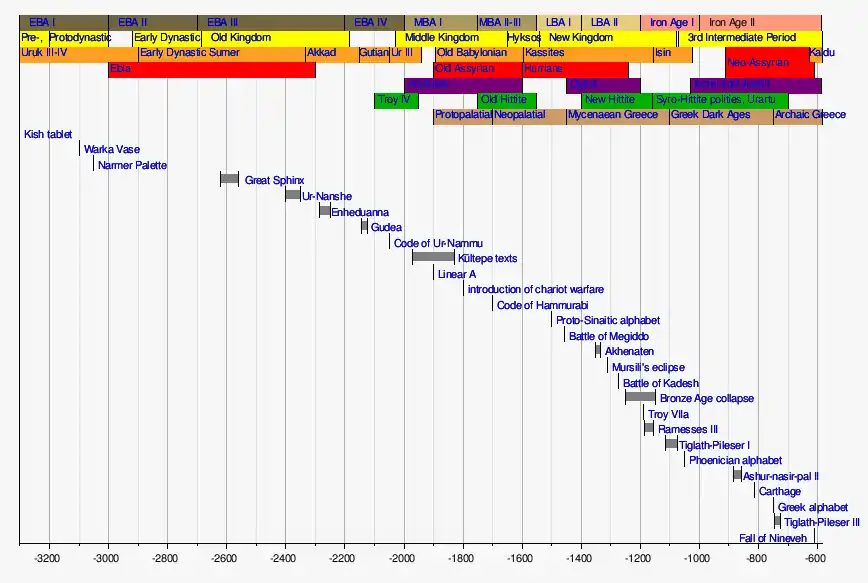

Assyria (/əˈsɪəriə/), also called the Assyrian Empire, was a Mesopotamian kingdom and empire of the ancient Near East in the area today known as the Levant that existed as a state from perhaps as early as the 25th century BC (in the form of the Assur city-state[5]) until its collapse between 612 BC and 609 BC — spanning the periods of the Early to Middle Bronze Age through to the late Iron Age.[6][7] This vast span of time is divided into the Early Period (2500–2025 BC), Old Assyrian Empire (2025–1378 BC), Middle Assyrian Empire (1392–934 BC) and Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC).

Assyria | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2500 BC–609 BC[1] | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Aššur (2500–1754 BC) Shubat-Enlil (1754–1681 BC) Aššur (1681–879 BC) Kalhu (879–706 BC) Dur-Sharrukin (706–705 BC) Nineveh (705–612 BC) Harran (612–609 BC) | ||||||||||

| Official languages | |||||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian Aramaic | ||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• c. 2500 BC | Tudiya (first) | ||||||||||

• 612–609 BC | Ashur-uballit II (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||||

• Kikkiya overthrown | 2500 BC | ||||||||||

• Decline of Assyria | 612 BC 609 BC[2] | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 194,249[3] km2 (75,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||

| Currency | Mina[4] | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

From the end of the seventh century BC (when the Neo-Assyrian state fell) to the mid-seventh century AD, it survived as a geopolitical entity,[8][9][10] for the most part ruled by foreign powers such as the Parthian[11] and early Sasanian Empires[12] between the mid-second century BC and late third century AD during which a number of independent Assyrian states such as Adiabene, Osroene, Beth Nuhadra and Beth Garmai arose. The final part of this period saw Mesopotamia become a major centre of Syriac Christianity and the birthplace of the Church of the East and Syriac Orthodox Church.[13] Greeks, Romans, and subsequently Arabs and Ottomans also took over control of the Assyrian lands.

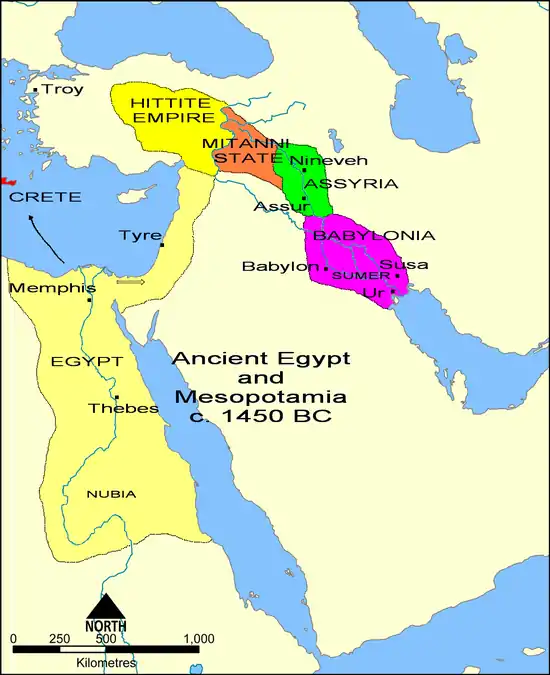

A Semitic-speaking realm, Assyria was centred on the Tigris in Upper Mesopotamia, in modern terms, northern Iraq, northeast Syria, and southeast Turkey. The Assyrians came to rule powerful empires in several periods. Making up a substantial part of the greater Mesopotamian "cradle of civilization", which included Sumer, the Akkadian Empire, and Babylonia, Assyria reached the height of technological, scientific and cultural achievements for its time. Starting around 900 BC, the Assyrians began campaigning to expand their empire and to dominate other people. They conquered, exacted tribute, building new fortified towns, palaces and tempels. By constant warfare the Assyrians created an empire[14] that stretched from eastern Libya and Cyprus in the East Mediterranean to Iran, and from present-day Armenia and Azerbaijan in the Transcaucasia to the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt in the south.[15]

The name "Assyria" originates with the Assyrian state's original capital, the ancient city of Aššur, which dates to c. 2600 BC — originally one of a number of Akkadian-speaking city-states in Mesopotamia. In the 25th and 24th centuries BC, Assyrian kings were pastoral leaders. From the late 24th century BC, the Assyrians became subject to Sargon of Akkad, who united all the Akkadian- and Sumerian-speaking peoples of Mesopotamia under the Akkadian Empire, which lasted from c. 2334 BC to 2154 BC.[16] After the Assyrian Empire fell, the greater remaining part of Assyria formed a geopolitical region and province of other empires, although between the mid-2nd century BC and late 3rd century AD a patchwork of small independent Assyrian kingdoms arose, including Assur, Adiabene, Osroene, Beth Nuhadra, Beth Garmai, and Hatra.

The region of Assyria fell under the successive control of the Median Empire of 620 to 549 BC, the Achaemenid Empire of 550 to 330 BC, the Macedonian Empire (late 4th century BC), the Seleucid Empire of 312 to 63 BC, the Parthian Empire of 247 BC to 224 AD, the Roman Empire (from 116 to 118 AD) and the Sasanian Empire of 224 to 651 AD. The Arab Islamic conquest of the area in the mid-seventh century finally dissolved Assyria (Assuristan, a region which by then also included the former Babylonia) as a single entity, after which the remnants of the Assyrian people (by now almost all Christians) gradually became an ethnic, linguistic, cultural and religious minority in the Assyrian homeland, surviving there to this day as an indigenous people of the region.[17][18]

Nomenclature

Assyria was also sometimes known as Subartu and Azuhinum prior to the rise of the city-state of Ashur, after which it became Aššūrāyu. After the fall of the Assyrian Empire, from 605 BC through to the late seventh century AD, people referred to the area variously as Achaemenid Assyria, Atouria, Ator, Athor, and sometimes as Syria - which etymologically derives from Assyria.[19] Strabo (died c. AD 24) references Syria (Greek), Assyria (Latin) and Asōristān (Middle Persian). "Assyria" can also refer to the geographic region or heartland where Assyria, its empires and the Assyrian people were (and still are) centered.

The indigenous modern Eastern Aramaic-speaking Assyrian Christian ethnic minority in northern Iraq, northeast Syria, southeast Turkey and northwest Iran are the descendants of the ancient Assyrians (see Assyrian continuity).[20][21] As Babylonia is called after the city of Babylon, Assyria means "land of Asshur".[3]

Etymologically, Assyria is connected to the name of Syria,[22] with both names ultimately deriving from the Akkadian Aššur.[23] Theodor Nöldeke in 1881 was the first to give philological support to the assumption that Syria and Assyria have the same etymology,[24] a suggestion going back to John Selden (1617). The 21st-century discovery of the Çineköy inscription also confirmed that Syria, being a Cilician and Greek corruption of the name Assyria, ultimately derives from the Assyrian term Aššūrāyu.[25]

Pre-history

In prehistoric times, the region that was to become known as Assyria (and Subartu) was home to a Neanderthal culture such as has been found at the Shanidar Cave. The earliest Neolithic sites in what will be Assyria were the Jarmo culture c. 7100 BC, the Halaf culture c. 6100 BC, and the Hassuna culture c. 6000 BC.

The Akkadian-speaking people (the earliest historically-attested Semitic-speaking people)[26] who would eventually found Assyria appear to have entered Mesopotamia at some point during the latter 4th millennium BC (c. 3500–3000 BC),[27] eventually intermingling with the earlier Sumerian-speaking population, who came from northern Mesopotamia,[28][29] with Akkadian names appearing in written record from as early as the 29th century BC.[26][30]

During the 3rd millennium BC, a very intimate cultural symbiosis developed between the Sumerians and the Akkadians throughout Mesopotamia, which included widespread bilingualism.[31] The influence of Sumerian (a language isolate) on Akkadian, and vice versa, is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.[31] This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the third millennium BC as a sprachbund.[31] Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere after the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate),[32] although Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the 1st century AD, as did use of the Akkadian cuneiform.

The cities of Assur, Nineveh, Gasur and Arbela together with a number of other towns and cities, existed since at least before the middle of the 3rd millennium BC (c. 2600 BC), although they appear to have been Sumerian-ruled administrative centres at this time, rather than independent states.

Greco-Roman classical writers such as Julius Africanus, Marcus Velleius Paterculus and Diodorus Siculus dated the founding of Assyria to various dates between 2284 BC and 2057 BC,[33][34][35] listing the earliest king as Belus or Ninus.

According to the Biblical generations of Noah, in Genesis chapter 10, the city of Aššur was allegedly founded by Ashur the son of Shem, who was deified by later generations as the city's patron god. However, the much older attested Assyrian tradition itself lists the first king of Assyria as the 25th century BC Tudiya, and an early urbanised Assyrian king named Ushpia (c. 2050 BC) as having dedicated the first temple to the god Ashur in the city in the mid-21st century BC. It is highly likely that the city was named in honour of its patron Assyrian god with the same name.

History

Early Period, 2600–2025 BC

Early Period | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2600 BC–c. 2025 BC | |||||||||

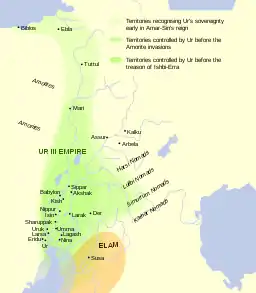

A map detailing the location of Assyria within the Ancient Near East c. 2500 BC | |||||||||

| Capital | Aššur | ||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian language Sumerian language | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• c. 2450 BC | Tudiya (first) | ||||||||

• c. 2025 BC | Ilu-shuma (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Established | c. 2600 BC | ||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 2025 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Iraq | ||||||||

The city of Aššur, together with a number of other Assyrian cities, seem to have been established by 2600 BC. However it is likely that they were initially Sumerian-dominated administrative centres. In the late 26th century BC, Eannatum of Lagash, then the dominant Sumerian ruler in Mesopotamia, mentions "smiting Subartu" (Subartu being the Sumerian name for Assyria). Similarly, in c. the early 25th century BC, Lugal-Anne-Mundu the king of the Sumerian state of Adab lists Subartu as paying tribute to him.

Of the early history of the kingdom of Assyria, little is known.[36] In the Assyrian King List, the earliest king recorded was Tudiya. According to Georges Roux he would have lived in the mid 25th century BC, i.e. c. 2450 BC. In archaeological reports from Ebla, it appeared that Tudiya's activities were confirmed with the discovery of a tablet where he concluded a treaty for the operation of a karum (trading colony) in Eblaite territory, with "king" Ibrium of Ebla (who is now known to have been the vizier of Ebla for king Ishar-Damu).

Tudiya was succeeded on the list by Adamu, the first known reference to the Semitic name Adam[37] and then a further thirteen rulers (Yangi, Suhlamu, Harharu, Mandaru, Imsu, Harsu, Didanu, Hanu, Zuabu, Nuabu, Abazu, Belus and Azarah). Nothing concrete is yet known about these names, although it has been noted that a much later Babylonian tablet listing the ancestral lineage of Hammurabi, the Amorite king of Babylon, seems to have copied the same names from Tudiya through Nuabu, though in a heavily corrupted form.

The earliest kings, such as Tudiya, who are recorded as kings who lived in tents, were independent semi-nomadic pastoralist rulers. These kings at some point became fully urbanised and founded the city state of Aššur in the mid 21st-century BC.[38]

Akkadian Empire and Neo-Sumerian Empires, 2334–2050 BC

During the Akkadian Empire (2334–2154 BC), the Assyrians, like all the Akkadian-speaking Mesopotamians (and also the Sumerians), became subject to the dynasty of the city-state of Akkad, centered in central Mesopotamia. The Akkadian Empire founded by Sargon the Great claimed to encompass the surrounding "four-quarters". The region of Assyria, north of the seat of the empire in central Mesopotamia, had also been known as Subartu by the Sumerians, and the name Azuhinum in Akkadian records also seems to refer to Assyria proper.[39] The Sumerians were eventually absorbed into the Akkadian (Assyro-Babylonian) population.[31][32]

Assyrian rulers were subject to Sargon and his successors, and the city of Ashur became a regional administrative center of the Empire, implicated by the Nuzi tablets.[40] During this period, the Akkadian-speaking Semites of Mesopotamia came to rule an empire encompassing not only Mesopotamia itself but large swathes of Asia Minor, ancient Iran, Elam, the Arabian Peninsula, Canaan and Syria.

Assyria seems to have already been firmly involved in trade in Asia Minor by this time; the earliest known reference to Anatolian karu in Hatti was found on later cuneiform tablets describing the early period of the Akkadian Empire (c. 2350 BC). On those tablets, Assyrian traders in Burushanda implored the help of their ruler, Sargon the Great, and this appellation continued to exist throughout the Assyrian Empire for about 1,700 years. The name "Hatti" itself even appears in later accounts of his grandson, Naram-Sin, campaigning in Anatolia.

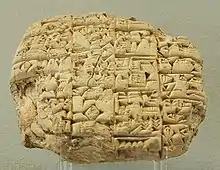

Assyrian and Akkadian traders spread the use of writing in the form of the Mesopotamian cuneiform script to Asia Minor and the Levant (modern Syria and Lebanon). However, towards the end of the reign of Sargon the Great, the Assyrian faction rebelled against him; "the tribes of Assyria of the upper country—in their turn attacked, but they submitted to his arms, and Sargon settled their habitations, and he smote them grievously".[41]

The Akkadian Empire was destroyed by economic decline and internal civil war, followed by attacks from barbarian Gutian people in 2154 BC. The rulers of Assyria during the period between c. 2154 BC and 2112 BC once again became fully independent, as the Gutians are only known to have administered southern Mesopotamia. However, the king list is the only information from Assyria for this period.

Most of Assyria briefly became part of the Neo-Sumerian Empire (or 3rd dynasty of Ur) founded in c. 2112 BC. Sumerian domination extended as far as the city of Ashur but appears not to have reached Nineveh and the far north of Assyria. One local ruler (shakkanakku) named Zāriqum (who does not appear on any Assyrian king list) is listed as paying tribute to Amar-Sin of Ur. Ashur's rulers appear to have remained largely under Sumerian domination until the mid-21st century BC (c. 2050 BC); the king list names Assyrian rulers for this period and several are known from other references to have also borne the title of shakkanakka or vassal governors for the neo-Sumerians.[42][43]

Old Assyrian Empire, 2025–1522 BC

Old Assyrian Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2025 BC–c. 1750 BC | |||||||||||

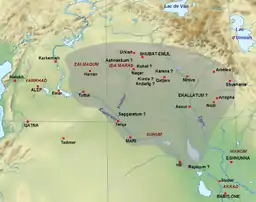

Map showing the approximate extent of the Upper Mesopotamian Empire at the death of Shamshi-Adad I c. 1721 BC. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Aššur | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian (official) Sumerian (official) Hittite Hurrian Amorite | ||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• c. 2025 BC | Erishum I (first) | ||||||||||

• c. 1393 BC | Ashur-nadin-ahhe II (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||||

• Established | c. 2025 BC | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 1750 BC | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Turkey | ||||||||||

The Old Assyrian Empire is one of four periods into which the history of Assyria is divided, the other three being: the Early Assyrian Period, the Middle Assyrian Period and the New Assyrian Period.

Ushpia (2080 BC) appears to have been the first fully urbanised independent king of Assyria, and is traditionally held to have dedicated temples to the god Ashur in the city of the same name.[44] He was followed by Sulili, Kikkiya and Akiya, of whom little is known aside from Kikkiya conducting various building works in Assur. A number of scholars also place Zariqum, a contemporary of Amar-Sin (2046–2038 BC) of Ur as an Assyrian ruler, though he does not appear on the Assyrian king list, but is claimed by Amar-Sin to be the 'governor' of Assur.[45]

In approximately 2025 BC, a king named Puzur-Ashur I came to the throne of Assyria, and there is some debate among scholars as to whether he was the founder of a new dynasty or a descendant of Ushpia. He is mentioned as having conducted building projects in Assur, and he and his successors took the title Išši’ak Aššur (meaning viceroy of Ashur). From this time Assyria began to expand trading colonies called Karum into Hurrian and Hattian lands in Anatolia.[46] He was succeeded by Shalim-ahum (c. 2000 BC), a king who is attested in a contemporary record of the time, leaving inscriptions in an archaic form of Akkadian.[47] In addition to the expansions into Anatolia Ilu-shuma (C. 1995–1974 BC) (Middle chronology) appears to have conducted military campaigns in southern Mesopotamia, either in conquest of the city-states of the south, or in order to protect his fellow Akkadian-speakers from incursions by Elamites from the east and/or Amorites from the west –

"The freedom[nb 1] of the Akkadians and their children I established. I purified their copper. I established their freedom from the border of the marshes and Ur and Nippur, Awal, and Kismar, Der of the god Ishtaran, as far as Assur."[48]:7–8

He is known to have built the old temple of Ishtar in Assur. He was succeeded by another powerful king, the long reigning Erishum I (1973–1934 BC) who is notable for one of the earliest examples of written legal codes[49] and introducing the limmu (eponym) lists that were to continue throughout Assyrian history. He is known to have greatly expanded Assyrian trading colonies in Anatolia, with twenty one being listed during his reign. These Karum traded in: tin, textiles, lapis lazuli, iron, antimony, copper, bronze, wool, and grain, in exchange for gold and silver. Erishum also kept numerous written records, and conducted major building works in Assyria, including the building of temples to Ashur, Ishtar and Adad.[50]

These policies were continued by Ikunum (1933–1921), Sargon I (1920–1881 BC), likely named after his predecessor Sargon of Akkad,[51] (during Sargon I's later reign Babylon was founded as a small city-state), and Puzur-Ashur II (1880–1873 BC). Naram-Sin (1872–1828 BC) repelled an attempted usurpation of his throne by the future king Shamshi-Adad I late in his reign, however his successor Erishum II was deposed by Shamshi-Adad I in 1809 BC, bringing an end to the dynasty founded either by Ushpia or Puzur-Ashur I.

Shamshi-Adad I (1808–1776 BC) was already the ruler of Terqa, and although he claimed Assyrian ancestry as a descendant of Ushpia, he is regarded as a foreign Amorite usurper by later Assyrian tradition. However, he greatly expanded the Old Assyrian Empire, incorporating the northern half of Mesopotamia, swathes of eastern and southern Anatolia and much of the Levant into his large empire, and campaigned as far west as the eastern shores of the Mediterranean.[52] His son and successor Ishme-Dagan I (1775–1764 BC) gradually lost territory in southern Mesopotamia and the Levant to the state of Mari and Eshnunna respectively, and had mixed relations with Hammurabi, the king who had turned the hitherto young and insignificant city-state of Babylon into a major power and empire.

After Shamsi-Adad I's death Assyria was reduced to vassalage by Hammurabi; Mut-Ashkur (1763–1753 BC), Rimush and Asinum were subservient to Hammurabi, who also took ownership of Assyrian trading colonies, thus bringing an end to the Old Assyrian Empire.

However, the Babylonian empire proved to be short lived, rapidly collapsing after the death of Hammurabi c. 1750 BC. An Assyrian governor named Puzur-Sin deposed Asinum who was regarded as a foreign Amorite and a puppet of the new and ineffectual Babylonian king Sumuabum, and the Babylonian and Amorite presence was expunged from Assyria by Puzur-Sin and his successor Ashur-dugul, who reigned for six years. A king called Adasi (1720–1701 BC) finally restored strength and stability to Assyria, ending the civil unrest that had followed the ejection of the Babylonians and Amorites, founding the new Adaside Dynasty.[53] Bel-bani (1700–1691 BC) succeeded Adasi and further strengthened Assyria against potential threats,[54] and remained a revered figure even in the time of Ashurbanipal over a thousand years later.[55]

There followed a long, prosperous and peaceful period in Assyrian history, rulers such as Libaya (1691–1674 BC), Sharma-Adad I, Iptar-Sin, Bazaya, Lullaya, Shu-Ninua and Sharma-Adad II appear to have had peaceful and largely uneventful reigns[56]

Assyria remained strong and secure; when Babylon was sacked and its Amorite rulers deposed by the Hittite Empire and subsequently fell to the Kassites in 1595 BC, both powers were unable to make any inroads into Assyria, and there seems to have been no trouble between the first Kassite ruler of Babylon, Agum II, and Erishum III (1598–1586 BC) of Assyria, and a mutually beneficial treaty was signed between the two rulers. Shamshi-Adad II (1585–1580 BC), Ishme-Dagan II (1579–1562 BC) and Shamshi-Adad III (1562–1548 BC) seem also to have had peaceful tenures, although few records have thus far been discovered about their reigns. Similarly, Ashur-nirari I (1547–1522 BC) seems not to have been troubled by the newly founded Mitanni Empire in Asia Minor, the Hittite empire, or Babylon during his 25-year reign. He and his successor Puzur-Ashur III (1521–1497 BC) are known to have been active kings, improving the infrastructure, dedicating temples and conducting various building projects throughout the kingdom. Enlil-nasir I, Nur-ili, Ashur-shaduni and Ashur-rabi I (who deposed his predecessor) followed.[57]

Decline, 1450–1393 BC

The emergence of the Hurri-Mitanni Empire and allied Hittite empire in the 16th century BCE did eventually lead to a short period of sporadic Mitannian-Hurrian domination in the latter half of the 15th century BCE. The Mitannians (an Indo-Aryan speaking people) are thought to have entered Anatolia from the north, conquered and formed the ruling class over the indigenous Hurrians of eastern Anatolia. The indigenous Hurrians spoke the Hurrian language, a language in the now wholly extinct Hurro-Urartian language family.

Ashur-nadin-ahhe I (1450–1431 BC) was courted by the Egyptians, who were rivals of Mitanni, and attempting to gain a foothold in the Near East. Amenhotep II sent the Assyrian king a tribute of gold to seal an alliance against the Hurri-Mitannian empire. It is likely that this alliance prompted Saushtatar, the emperor of Mitanni, to invade Assyria, and sack the city of Ashur, after which Assyria became a sometime vassal state. Ashur-nadin-ahhe I was deposed, either by Shaustatar or by his own brother Enlil-nasir II (1430–1425 BC) in 1430 BC, who then paid tribute to the Mitanni. Ashur-nirari II (1424–1418 BC) had an uneventful reign and appears to have also paid tribute to the Mitanni Empire.

The Assyrian monarchy survived, and the Mitannian influence appears to have been short-lived.

They appear not to have been always willing or indeed able to interfere in Assyrian internal and international affairs.

Ashur-bel-nisheshu (1417–1409 BC) seems to have been independent of Mitannian influence, as evidenced by his signing a mutually beneficial treaty with Karaindash, the Kassite king of Babylonia in the late 15th century. He also undertook extensive rebuilding work in Ashur itself, and Assyria appears to have redeveloped its former highly sophisticated financial and economic systems during his reign. Ashur-rim-nisheshu (1408–1401 BC) also undertook building work, strengthening the city walls of the capital. Ashur-nadin-ahhe II (1400–1393 BC) also received a tribute of gold and diplomatic overtures from Egypt, probably in an attempt to gain Assyrian military support against Egypt's Mitannian and Hittite rivals in the region. However, the Assyrian king appears not to have been in a strong enough position to challenge Mitanni or the Hittites.

Eriba-Adad I (1392–1366 BC), a son of Ashur-bel-nisheshu, ascended the throne in 1392 BC and finally broke the ties to the Mitanni Empire, and instead turned the tables, and began to exert Assyrian influence on the Mitanni.

Middle Assyrian Empire 1392–1056 BC

Middle Assyrian Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1392 BC–934 BC | |||||||||

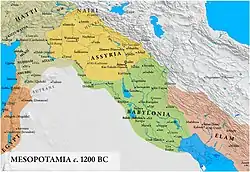

Map of the Ancient Near East during the Amarna Period (14th century BC), showing the great powers of the day: Egypt (orange), Hatti (blue), the Kassite kingdom of Babylon (black), Assyria (yellow), and Mitanni (brown). The extent of the Achaean/Mycenaean civilization is shown in purple. | |||||||||

| Capital | Aššur | ||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian language (official) Hittite Hurrian | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1365–1330 BC | Ashur-uballit I (first) | ||||||||

• 967–934 BC | Tiglath-Pileser II (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Mesopotamia | ||||||||

• Independence from Mitanni | 1392 BC | ||||||||

• Reign of Ashur-dan II | 934 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Middle period (1365 BC–1056 BC) saw reigns of great kings, such as Ashur-uballit I, Arik-den-ili, Tukulti-Ninurta I and Tiglath-Pileser I. During this period, Assyria overthrew the empire of the Hurri-Mitanni and eclipsed the Hittite Empire, Egyptian Empire, Babylonia, Elam, Canaan and Phrygia in the Near East.[58]

By the reign of Eriba-Adad I (1392–1366 BC) Mitanni influence over Assyria was on the wane. Eriba-Adad I became involved in a dynastic battle between Tushratta and his brother Artatama II and after this his son Shuttarna III, who called himself king of the Hurri while seeking support from the Assyrians.

Ashur-uballit I (1365–1330 BC) went further, defeating Shuttarna III and bringing an end to the Mitanni empire, the Assyrian king then annexing its territories in Anatolia and the Levant, turning Assyria once more into a major empire.[59] The ambitious Assyrian king went further still, attacking and conquering Babylonia, and imposing a puppet ruler loyal to himself upon its throne. Assyria then annexed hitherto Babylonian territory in central Mesopotamia.[60] Enlil-nirari (1330–1319 BC) also defeated Babylonia's Kassite kings.

The Hittites, having failed to save Mitanni, allied with Babylon in an unsuccessful economic war against Assyria for many years. Assyria was now a large and powerful empire, and a major threat to Egyptian and Hittite interests in the region, and was perhaps the reason that these two powers, fearful of Assyrian might, made peace with one another.[61]

Arik-den-ili (1318–1307 BC) campaigned further still, entering northern Ancient Iran and subjugating the 'pre-Iranic' Gutians, Turukku and Nigimhi, before campaigning deeper into the Levant, subjugating the Suteans, Ahlamu and Yauru.[62] His successor Adad-nirari I (1307–1275 BC) was another highly successful military leader, he defeated and conquered the Hurro-Mitanni kingdom of Hanigalbat and the rest of the independent Hurro-Mitanni kingdoms of Anatolia, despite the Hittites attempting to support their allies, and inflicted a crushing defeat on Babylonia at the Battle of Kār Ištar, annexing large swathes of Babylonian territory. Hittite kings during his reign assumed a placatory attitude towards the Assyrian king.[63][64]

Shalmaneser I (1274–1245 BC) conquered eight kingdoms in central Anatolia in his first year, and in the next he defeated a coalition of Hittites, Hurrians, Mitanni and Ahlamu, annexing yet more territory in Anatolia and the Levant, and retaining Assyrian dominion over Babylonia and the northwest of ancient Iran. Shalmaneser also conducted extensive building work in Assur, Nineveh and Arbela, and founded the city of Kalhu (the Biblical Calah/Nimrud).[65][66]

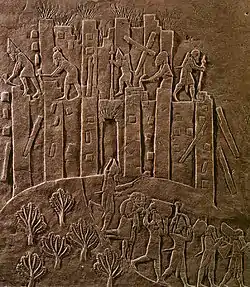

Shalmaneser's son and successor, Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1207 BC), won a major victory against the Hittites and their king Tudhaliya IV at the Battle of Nihriya and took thousands of prisoners. Rather than being content to simply subjugate Babylonian kings as his predecessors had, he conquered Babylonia directly, taking Kashtiliash IV as a captive and ruled there himself as king for seven years, taking on the old title "King of Sumer and Akkad" first used by Sargon of Akkad. Tukulti-Ninurta I thus became the first Akkadian speaking native Mesopotamian to rule the state of Babylonia, its founders having been foreign Amorites, succeeded by equally foreign Kassites. Tukulti-Ninurta petitioned the god Shamash before beginning his counter offensive.[67] Kashtiliash IV was captured, single-handed by Tukulti-Ninurta according to his account, who "trod with my feet upon his lordly neck as though it were a footstool"[15] and deported him ignominiously in chains to Assyria. The victorious Assyrians demolished the walls of Babylon, massacred many of the inhabitants, pillaged and plundered his way across the city to the Esagila temple, where he made off with the statue of Marduk.[68]

Middle Assyrian texts recovered at ancient Dūr-Katlimmu, include a letter from Tukulti-Ninurta to his sukkal rabi'u, or grand vizier, Ashur-iddin advising him of the approach of his general Shulman-mushabshu escorting the captive Kashtiliash, his wife, and his retinue which incorporated a large number of women,[69] on his way to exile after his defeat. In the process he defeated the Elamites, who had themselves coveted Babylon. He also wrote an epic poem documenting his victorious wars against Babylon and Elam. He progressed further south into what is today Arabia, conquering the pre-Arab South Semitic kingdoms of Dilmun and Meluhha. After a Babylonian revolt, he raided and plundered the temples in Babylon, regarded as an act of sacrilege. As relations with the priesthood in Ashur began deteriorating, Tukulti-Ninurta built a new capital city; Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta.[70]

A series of short reigning kings followed, these being Ashur-nadin-apli (1207–1204 BC), Ashur-nirari III (1203–1198 BC), Enlil-kudurri-usur (1197–1193 BC) and Ninurta-apal-Ekur (1192–1190 BC), and there were no significant expansions of the empire during their short tenures, and Babylonia seems to have freed itself from the Assyrian yoke for a time.

Ashur-dan I (1190–1144 BC) conquered huge swathes of Babylonia, subjugating its king, and taking much booty home to Assyria. However, this led to conflict with the powerful Elamites of the southwest of ancient Iran, who were themselves preying upon Babylonia. The Elamites managed to actually take the Assyrian city of Arrapha (modern Kirkuk), before being finally defeated and driven from the Assyrian empire.[71] Civil unrest ensued in Assyria after Ashur-Dan I's death, and Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur and Mutakkil-Nusku followed in quick succession during 1133 BC.

Ashur-resh-ishi I (1133–1116 BC) restored the tradition of powerful conquering kings. He campaigned to the east, taking the Zagros region of ancient Iran, and subjugated the Amorites, Ahlamu and the newly appeared Arameans in the Levant. He also defeated the ambitious Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylonia, annexing Babylonian territory in the process.[72]

Tiglath-pileser I (1115–1074 BC) proved to be a long reigning and all conquering ruler, who firmly underlined Assyria's position as the world's leading military power.[73]

His first campaign was against the Phrygians and Kaskians in 1112 BC, who had attempted to occupy certain Assyrian ruled Hittite districts in the Upper Euphrates; then he overran Commagene and eastern Cappadocia, and drove the Hittites from the Assyrian province of Subartu, northeast of Malatia.[74]

In a subsequent campaign, the Assyrian forces penetrated into the mountains south of Lake Van and then turned westward to receive the submission of Malatia and Urartu. In his fifth year, Tiglath-Pileser attacked Cilicia and Comana in Cappadocia, and placed a record of his victories engraved on copper plates in a fortress he built to secure his Cilician conquests.[74]

The Aramaeans of northern and central Syria were the next targets of the Assyrian king, who made his way as far as the sources of the Tigris.[75] The control of the high road to the Mediterranean was secured by the possession of the Hittite town of Pitru[76] at the junction between the Euphrates and Sajur; thence he proceeded to conquer the Canaanite/Phoenician city-states of Byblos, Tyre, Sidon, Simyra, Berytus (Beirut), Aradus and finally Arvad where he embarked onto a ship to sail the Mediterranean, on which he killed a nahiru or "sea-horse" (which A. Leo Oppenheim translates as a narwhal) in the sea.[75] He was passionately fond of hunting and was also a great builder. The general view is that the restoration of the temple of the gods Ashur and Hadad at the Assyrian capital of Assur (Ashur) was one of his initiatives.[75] He was succeeded by Asharid-apal-Ekur who reigned for only a short time.

Ashur-bel-kala (1073–1056 BC) kept the vast empire together, campaigning successfully against Urartu and Phrygia to the north and the Arameans to the west. He maintained friendly relations with Marduk-shapik-zeri of Babylon, however upon the death of that king, he invaded Babylonia and deposed the new ruler Kadašman-Buriaš, appointing Adad-apla-iddina as his vassal in Babylon. He built some of the earliest examples of both Zoological Gardens and Botanical Gardens in Ashur, collecting all manner of animals and plants from his empire, and receiving a collection of exotic animals as tributes from Egypt.

Late in his reign, the Middle Assyrian Empire erupted into civil war, when a rebellion was orchestrated by Tukulti-Mer, a pretender to the throne of Assyria. Ashur-bel-kala eventually crushed Tukulti-Mer and his allies, however the civil war in Assyria had allowed hordes of Arameans to take advantage of the situation, and press in on Assyrian controlled territory from the west. Ashur-bel-kala counterattacked them, and conquered as far as Carchemish and the source of the Khabur river, but by the end of his reign many of the areas of Syria and Phoenicia-Canaan to the west of these regions as far as the Mediterranean, previously under firm Assyrian control, were eventually lost to the Middle Assyrian Empire.

Society and law in the Middle Assyrian Period

The Middle Assyrian kingdom was well organized, and in the firm control of the king, who also functioned as the High Priest of Ashur, the state god. He had certain obligations to fulfill in the cult, and had to provide resources for the temples. The priesthood became a major power in Assyrian society. Conflicts with the priesthood are thought to have been behind the murder of king Tukulti-Ninurta I.

The Middle Assyrian Period was marked by the long wars fought that helped build Assyria into a warrior society. The king depended on both the citizen class and priests in his capital, and the landed nobility who supplied the horses needed by Assyria's military. Documents and letters illustrate the importance of the latter to Assyrian society. Assyria needed less artificial irrigation than Babylonia, and horse-breeding was extensive. Portions of elaborate texts about the care and training of them have been found. Trade was carried out in all directions. The mountain country to the north and west of Assyria was a major source of metal ore, as well as lumber. Economic factors were a common casus belli.

All free male citizens were obliged to serve in the army for a time, a system which was called the ilku-service. A legal code was produced during the 14th and 13th centuries which, among other things, clearly shows that the social position of women in Assyria was lower than that of neighbouring societies. Men were permitted to divorce their wives with no compensation paid to the latter. If a woman committed adultery, she could be beaten or put to death. It's not certain if these laws were seriously enforced, but they appear to be a backlash against some older documents that granted things like equal compensation to both partners in divorce.

The women of the king's harem and their servants were also subject to harsh punishments, such as beatings, mutilation, and death. Assyria, in general, had much harsher laws than most of the region. Executions were not uncommon, nor were whippings followed by forced labour. Some offenses allowed the accused a trial under torture or duress. One tablet that covers property rights has brutal penalties for violators. A creditor could force debtors to work for him, but not sell them.

In the Middle Assyrian Laws, sex crimes were punished identically whether they were homosexual or heterosexual.[77] An individual faced no punishment for penetrating a cult prostitute, someone of an equal or lower social class, such as slaves, or someone whose gender roles were not considered solidly masculine. Such sexual relations were even seen as good fortune.[78] However, homosexual relationships with royal attendants, between soldiers, or with those where a social better was submissive or penetrated were either treated as rape or seen as bad omens, and punishments applied.[77]

Furthermore, the article 'Homosexualität' in Reallexicon der Assyriologie states, "Homosexuality in itself is thus nowhere condemned as licentiousness, as immorality, as social disorder, or as transgressing any human or divine law. Anyone could practice it freely, just as anyone could visit a prostitute, provided it was done without violence and without compulsion, and preferably as far as taking the passive role was concerned, with specialists. That there was nothing religiously amiss with homosexual love between men is seen by the fact that they prayed for divine blessing on it."[79][80][81]

Assyria during the Bronze Age Collapse, 1200–936 BC

The Bronze Age Collapse from 1200 BC to 900 BC was a Dark Age for the entire Near East, North Africa, Asia Minor, Caucasus, Mediterranean and Balkan regions, with great upheavals and mass movements of people.

Assyria and its empire were not unduly affected by these tumultuous events for some 150 years, perhaps the only ancient power that was not, and in fact thrived for most of the period. However, upon the death of Ashur-bel-kala in 1056 BC, Assyria went into a comparative decline for the next 100 or so years. The empire shrank significantly, and by 1020 BC Assyria appears to have controlled only areas close to Assyria itself, essential to keeping trade routes open in eastern Aramea, South Eastern Asia Minor, central Mesopotamia and north western Iran.

New West Semitic-speaking peoples such as the Arameans and Suteans moved into areas to the west and south of Assyria, including overrunning much of Babylonia to the south, Indo-European speaking Iranic peoples such as the Medes, Persians, Sarmatians and Parthians moved into the lands to the east of Assyria, displacing the native Kassites and Gutians and pressuring Elam and Mannea (all of which ancient non-Indo-European civilisations of Ancient Iran), and to the north in Asia Minor the Phrygians overran that part of the Hittites not already destroyed by Assyria, and Lydia emerged, a new Hurrian state named Urartu arose in the Caucasus, and Cimmerians, Colchians (Georgians) and Scythians around the Black Sea and Caucasus. Egypt was divided and in disarray, and Israelites were battling with other West Asian peoples such as the Amalekites, Moabites, Edomites and Ammonites and the non-Semitic-speaking Peleset/Philistines (who have been conjectured to be one of the so-called Sea Peoples)[82][83] for the control of southern Canaan. Dorian Greeks usurped the earlier Mycenaean Greeks in western Asia Minor, and the Sea Peoples ravaged the Eastern Mediterranean.

Other new peoples, such as the Chaldeans, Sarmatians, Arabs, Nubians and Kushites were to emerge later, during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC).

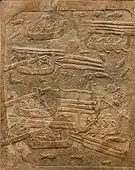

_Central_Palace_Tiglath_pileser_III_728_BCE_British_Museum_AG.jpg.webp)

Despite the apparent weakness of Assyria in comparison to its former might, at heart it in fact remained a solid, well defended nation whose warriors were the best in the world.[53] Assyria, with its stable monarchy, powerful army and secure borders was in a stronger position during this time than potential rivals such as Egypt, Babylonia, Elam, Phrygia, Urartu, Persia, Lydia and Media. Kings such as Eriba-Adad II, Ashur-rabi II, Ashurnasirpal I, Tiglath-Pileser II and Ashur-Dan II successfully defended Assyria's borders and upheld stability during this tumultuous time.

Assyrian kings during this period appear to have adopted a policy of maintaining and defending a compact, secure nation and satellite colonies immediately surrounding it, and interspersed this with sporadic punitive raids and invasions of neighbouring territories when the need arose, including campaigning as far as the Mediterranean and sacking Babylonia.

Neo-Assyrian Empire

Neo-Assyrian Empire | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 911 BC–609 BC[84] | |||||||||||||||||||

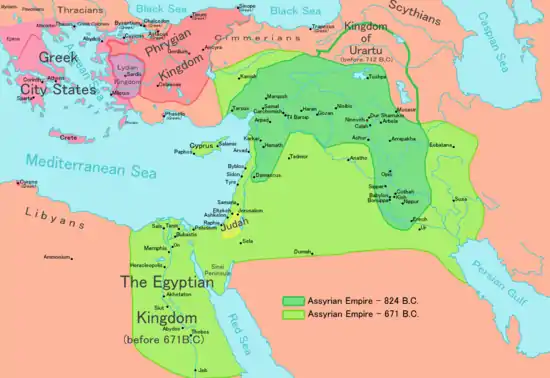

The Neo-Assyrian empire at its greatest extent, 671 BC | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Aššur 911 BC Kalhu 879 BC Dur-Sharrukin 706 BC Nineveh 705 BC Harran 612 BC | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian (official) Aramaic (official) Sumerian (declining) Hittite Hurrian Phoenician Egyptian | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||

• 911–891 BC | Adad-nirari II (first) | ||||||||||||||||||

• 612–609 BC | Ashur-uballit II (last) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||||||||||||

• Reign of Adad-nirari II | 911 BC | ||||||||||||||||||

| 612 BC | |||||||||||||||||||

| 609 BC[85] | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The Neo-Assyrian Empire is usually considered to have begun with the ascension of Adad-nirari II, in 911 BC, lasting until the fall of Nineveh at the hands of the Medes/Persians and Babylonians, Chaldeans in 609 BC.[86]

Assyria maintained a large and thriving rural population, combined with a number of well fortified cities, Major Assyrian cities during this period included; Nineveh, Assur, Kalhu (Calah, Nimrud), Arbela (Erbil), Arrapha (Karka, Kirkuk), Dur-Sharrukin, Imgur-Enlil, Carchemish, Harran, Tushhan, Til-Barsip, Ekallatum, Kanesh, Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, Urhai (Edessa), Guzana, Kahat, Amid (Diyarbakir), Mérida (Mardin, Tabitu, Nuhadra (Dohuk), Ivah, Sepharvaim, Rachae, Purushanda, Sabata, Birtha (Tikrit), Tell Shemshara, Dur-Katlimmu and Shekhna.

Assyria is often noted for its brutality and cruelty during this period, although Assyrian harshness was reserved solely for those who took up arms against the Assyrian king, and none of the Assyrian kings of the Neo-Assyrian Empire or preceding Middle Assyrian Empire conducted genocides, massacres or ethnic cleansings against civilian populations, non-combatant men, or women and children.[87][88] However, the monument of Ashurnasirpal II describing his conquest of one city states: "Of some, I cut off their feet and hands; of others I cut off their ears, noses and lips; of the young men's ears I made a heap; of the old men's heads I made a minaret. . . . The male children and female children I burned in the flames of the city."

Expansion, 911–627 BC

Assyria once more began to expand with the rise of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC. He cleared Aramean and other tribal peoples from Assyria's borders and began to expand in all directions into Anatolia, Ancient Iran, Levant and Babylonia.

Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) continued this expansion apace, subjugating much of the Levant to the west, the newly arrived Persians and Medes to the east, annexed central Mesopotamia from Babylon to the south, and expanded deep into Asia Minor to the north. He moved the capital from Ashur to Kalhu (Calah/Nimrud) and undertook impressive building works throughout Assyria. Shalmaneser III (859–824 BC) projected Assyrian power even further, conquering to the foothills of the Caucasus, Israel and Aram-Damascus, and subjugating Persia and the Arabs who dwelt to the south of Mesopotamia, as well as driving the Egyptians from Canaan. It was during the reign of Shalmaneser III that the Arabs and Chaldeans first enter the pages of recorded history.

Little further expansion took place under Shamshi-Adad V and his successor, the regent queen Semiramis, however when Adad-nirari III (811–783 BC) came of age, he took the reins of power from mother and set about a relentless campaign of conquest; subjugated the Arameans, Phoenicians, Philistines, Israelites, Neo-Hittites and Edomites, Persians, Medes and Manneans, penetrating as far as the Caspian Sea. He invaded and subjugated Babylonia, and then the migrant Chaldean and Sutean tribes settled in south eastern Mesopotamia whom he conquered and reduced to vassalage.

After the reign of Adad-nirari III, Assyria entered a period of instability and decline, losing its hold over most of its vassal and tributary territories by the middle of the 8th century BC, until the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC). He created the world's first professional army, introduced Imperial Aramaic as the lingua franca of Assyria and its vast empire, and reorganised the empire drastically. Tiglath-Pileser III conquered as far as the East Mediterranean, bringing the Greeks of Cyprus, Phoenicia, Judah, Philistia, Samaria and the whole of Aramea under Assyrian control. Not satisfied with merely holding Babylonia in vassalage, Tiglath-Pileser deposed its king and had himself crowned king of Babylon. The imperial, economic, political, military and administrative reforms of Tiglath-Pileser III were to prove a blueprint for future empires, such as those of the Persians, Greeks, Romans, Carthaginians, Byzantines, Arabs and Turks.

Shalmaneser V reigned only briefly, but once more drove the Egyptians from southern Canaan, where they were fomenting revolt against Assyria. Sargon II quickly took Samaria, effectively ending the northern Kingdom of Israel and carrying 27,000 people away into captivity into the Israelite diaspora. He was forced to fight a war to drive out the Scythians and Cimmerians who had attempted to invade Assyria's vassal states of Persia and Media. The Neo-Hittite states of northern Syria were conquered, as well as Cilicia. Lydia and Commagene. King Midas of Phrygia, fearful of Assyrian power, offered his hand in friendship. Elam was defeated and Babylonia and Chaldea reconquered. He made a new capital city named Dur Sharrukin. He was succeeded by his son Sennacherib who moved the capital to Nineveh and made the deported peoples work on improving Nineveh's system of irrigation canals. Nineveh was transformed into the largest city in the world at the time.

Esarhaddon had Babylon rebuilt, he imposed a vassal treaty upon his Persian, Median and Parthian subjects, and he once more defeated the Scythes and Cimmerians. Tiring of Egyptian interference in the Assyrian Empire, Esarhaddon decided to conquer Egypt. In 671 BC he crossed the Sinai Desert, invaded and took Egypt with surprising ease and speed. He drove its foreign Nubian/Kushite and Ethiopian rulers out, destroying the Kushite Empire in the process. Esarhaddon declared himself "king of Egypt, Libya, and Kush". Esarhaddon stationed a small army in northern Egypt and describes how; "All Ethiopians (read Nubians/Kushites) I deported from Egypt, leaving not one left to do homage to me". He installed native Egyptian princes throughout the land to rule on his behalf.

Under Ashurbanipal (669–627 BC), an unusually well educated king for his time who could speak, read and write in Sumerian, Akkadian and Aramaic, Assyrian domination spanned from the Caucasus Mountains (modern Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan) in the north to Nubia, Egypt, Libya and Arabia in the south, and from the East Mediterranean, Cyprus and Antioch in the west to Persia, Cissia and the Caspian Sea in the east.

Ultimately, Assyria conquered Babylonia, Chaldea, Elam, Media, Persia, Urartu (Armenia), Phoenicia, Aramea/Syria, Phrygia, the Neo-Hittite States, the Hurrian lands, Arabia, Gutium, Israel, Judah, Samarra, Moab, Edom, Corduene, Cilicia, Mannea, and Cyprus, and defeated and/or exacted tribute from Scythia, Cimmeria, Lydia, Nubia, Ethiopia and others. At its height, the Empire encompassed the whole of the modern nations of Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Cyprus, together with large swathes of Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Sudan, Libya, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan.

Downfall, 626–609 BC

The Assyrian Empire was severely crippled following the death of Ashurbanipal in 627 BC, the nation and its empire descending into a prolonged and brutal series of civil wars involving three rival kings, Ashur-etil-ilani, Sin-shumu-lishir and Sin-shar-ishkun. Egypt's 26th Dynasty, which had been installed by the Assyrians as vassals, quietly detached itself from Assyria, although it was careful to retain friendly relations.

The Scythians and Cimmerians took advantage of the bitter fighting among the Assyrians to raid Assyrian colonies, with hordes of horse-borne marauders ravaging parts of Asia Minor and the Caucasus, where the vassal kings of Urartu and Lydia begged their Assyrian overlord for help in vain. They also raided the Levant, Israel and Judah (where Ashkelon was sacked by the Scythians) and all the way into Egypt whose coasts were ravaged and looted with impunity.

The Iranic peoples under the Medes, aided by the previous Assyrian destruction of the hitherto dominant Elamites of Ancient Iran, also took advantage of the upheavals in Assyria to coalesce into a powerful Median-dominated force which destroyed the pre-Iranic kingdom of Mannea and absorbed the remnants of the pre-Iranic Elamites of southern[Iran, and the equally pre-Iranic Gutians, Manneans and Kassites of the Zagros Mountains and the Caspian Sea.

Cyaxares (technically a vassal of Assyria), in an alliance with the Scythians and Cimmerians, launched a surprise attack on a civil war beleaguered Assyria in 615 BC, sacking Kalhu (the Biblical Calah/Nimrud) and taking Arrapha (modern Kirkuk) and Gasur. Nabopolassar, still pinned down in southern Mesopotamia by Assyrian forces, was completely uninvolved in this major breakthrough against Assyria.

Despite the sorely depleted state of Assyria, bitter fighting ensued; throughout 614 BC the Medes continued to gradually make hard fought inroads into Assyria itself, scoring a decisive and devastating victory over the Assyrian forces at the battle of Assur.[89] In 613 BC, however, the Assyrians scored a number of counterattacking victories over the Medes-Persians, Babylonians-Chaldeans and Scythians-Cimmerians. This led to the unification of the forces ranged against Assyria who launched a massive combined attack, finally besieging and entering Nineveh in late 612 BC, with Sin-shar-ishkun being slain in the bitter street by street fighting. Despite the loss of almost all of its major cities, and in the face of overwhelming odds, Assyrian resistance continued under Ashur-uballit II (612–609 BC), who fought his way out of Nineveh and coalesced Assyrian forces around Harran which finally fell in 609 BC. The same year, Ashur-uballit II besieged Harran with the help of the Egyptian army, but this failed too, and this last defeat ended the Assyrian Empire.[89][90][91] During the aftermath, Egypt, along with remnants of the Assyrian army, suffered a defeat at the battle of Carchemish, in 605 BC, but the Assyrian troops did not participate to this battle as the army of the Assyrian state because certainly by 609 BC at the very latest,[92][93] Assyria had been destroyed as an independent political entity, although it was to launch major rebellions against the Achaemenid Empire in 546 BC and 520 BC, and remained a geo-political region, ethnic entity and colonised province.

Achaemenid Assyria, Osroene, Asōristān, Athura and Hatra

_(14747728556).jpg.webp)

Assyria was initially ruled by the short-lived Median Empire (609–549 BC) after its fall. In a twist of fate, Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon (together with his son and co-regent Belshazzar), was himself an Assyrian from Harran. He had overthrown the short-lived Chaldean dynasty in Babylonia, after which the Chaldeans disappeared from history, being fully absorbed into the native population of Babylonia. However, apart from plans to dedicate religious temples in the city of Harran, Nabonidus showed little interest in rebuilding Assyria. Nineveh and Kalhu remained in ruins with only small numbers of Assyrians living within them; conversely, a number of towns and cities, such as Arrapkha, Guzana, Nohadra and Harran, remained intact, and Assur and Arbela (Irbil) were not completely destroyed, as is attested by their later revival. However, Assyria spent much of this short period in a degree of devastation, following its fall.

Achaemenid Assyria (549–330 BC)

.jpg.webp)

After the Medes were overthrown by the Persians as the dominant force in Ancient Iran, Assyria was ruled by the Persian Achaemenid Empire (as Athura) from 549 BC to 330 BC (see Achaemenid Assyria). Between 546 and 545 BC, Assyria rebelled against the new Persian Dynasty, which had usurped the previous Median dynasty. The rebellion centered around Tyareh was eventually quashed by Cyrus the Great.

Assyria seems to have recovered dramatically, and flourished during this period. It became a major agricultural and administrative centre of the Achaemenid Empire, and its soldiers were a mainstay of the Persian Army.[94] In fact, Assyria even became powerful enough to raise another full-scale revolt against the Persian empire in 520–519 BC.

The Persians had spent centuries under Assyrian domination (their first ruler Achaemenes and his successors, having been vassals of Assyria), and Assyrian influence can be seen in Achaemenid art, infrastructure and administration. Early Persian rulers saw themselves as successors to Ashurbanipal, and Mesopotamian Aramaic was retained as the lingua franca of the empire for over two hundred years, and Greek writers such as Thucydides still referred to it as the Assyrian language.[95] Nineveh was never rebuilt however, and 200 years after it was sacked Xenophon reported only small numbers of Assyrians living amongst its ruins. Conversely the ancient city of Assur once more became a rich and prosperous entity.[96]

It was in 5th century BC Assyria that the Syriac language and Syriac script evolved. Five centuries later these were later to have a global influence as the liturgical language and written script for Syriac Christianity and its accompanying Syriac literature which also emerged in Assyria before spreading throughout the Near East, Asia Minor, The Caucasus, Central Asia, the Indian Subcontinent and China.

Macedonian and Seleucid Assyria

In 332 BC, Assyria fell to Alexander the Great, the Macedonian Emperor, who called the inhabitants Assyrioi. The Macedonian Empire (332–312) was partitioned in 312 BC. It thereafter became part of the Seleucid Empire (312 BC). It is from this period that the later Syria vs Assyria naming controversy arises, the Seleucids applied the name 'Syria' which is a 9th-century BC Indo-Anatolian derivation of 'Assyria' (see Etymology of Syria) not only to Assyria itself, but also to the Levantine lands to the west (historically known as Aram and Eber Nari), which had been part of the Assyrian empire but, the north east corner aside, never a part of Assyria proper.

When the Seleucids lost control of Assyria proper, the name Syria survived but was erroneously applied not only to the land of Assyria itself, but also now to Aramea (also known as Eber Nari) to the west that had once been part of the Assyrian empire, but apart from the north eastern corner, had never been a part of Assyria itself, nor inhabited by Assyrians. This was to lead to both the Assyrians from Northern Mesopotamia and the Arameans and Phoenicians from the Levant being collectively dubbed Syrians (and later also Syriacs) in Greco-Roman and later European culture, regardless of ethnicity, history or geography.

During Seleucid rule, Assyrians ceased to hold the senior military, economic and civil positions they had enjoyed under the Achaemenids, being largely replaced by Greeks. The Greek language also replaced Mesopotamian East Aramaic as the lingua franca of the empire, although this did not affect the Assyrian population themselves, who were not Hellenised during the Seleucid era.

During the Seleucid period in southern Mesopotamia, Babylon was gradually abandoned in favour of a new city named Seleucia on the Tigris, effectively bringing an end to Babylonia as a geo-political entity.

Parthian Assyria (150 BC – 225 AD)

By 150 BC, Assyria was largely under the control of the Parthian Empire. The Parthians seem to have exercised only loose control over Assyria, and between the mid 2nd century BC and 4th century AD a number of Neo-Assyrian states arose; these included the ancient capital of Assur itself, Adiabene with its capital of Arbela (modern Irbil), Beth Nuhadra with its capital of Nohadra (modern Dohuk), Osroene, with its capitals of Edessa and Amid (modern Sanliurfa and Diyarbakir), Hatra, and "ܒܝܬܓܪܡܝ" (Beth Garmai) with its capital at Arrapha (modern Kirkuk).[97] Adiabenian rulers converted to Judaism from paganism in the 1st century.[98] After 115 AD, there are no historic traces of Jewish royalty in Adiabene.

These freedoms were accompanied by a major Assyrian cultural revival, and temples to the Assyrian national gods Ashur, Sin, Hadad, Ishtar, Ninurta, Tammuz and Shamash were once more dedicated throughout Assyria and Upper Mesopotamia during this period.[99]

In addition, Christianity arrived in Assyria soon after the death of Christ and the Assyrians began to gradually convert to Christianity from the ancient Mesopotamian religion during the period between the early first and third centuries. Assyria became an important centre of Syriac Christianity and Syriac Literature, with the Church of the East evolving in Assyria, and the Syriac Orthodox Church partly also, with Osroene becoming the first independent Christian state in history.[13]

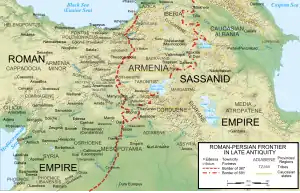

Roman Assyria (116–118)

However, in 116, under Trajan, Assyria and its independent states were briefly taken over by Rome as the province of Assyria. The Assyrian kingdom of Adiabene was destroyed as an independent state during this period. Roman rule lasted only a few years, and the Parthians once more regained control with the help of the Assyrians, who were incited to overthrow the Roman garrisons by the Parthian king. However, a number of Assyrians were conscripted into the Roman Army, with many serving in the region of Hadrian's Wall in Roman Britain, and inscriptions in Aramaic made by soldiers have been discovered in Northern England dating from the second century.[100]

With loose Parthian rule restored, Assyria and its patchwork of states continued much as they had before the Roman interregnum, although Assyria and Mesopotamia as a whole became a front line between the Roman and Parthian empires. Other new religious movements also emerged in the form of gnostic sects such as Mandeanism, as well as the now extinct Manichean religion.

Sassanid Assyria (226 – c. 650)

In 226, Assyria was largely taken over by the Sasanian Empire. After driving out the Romans and Parthians, the Sassanid rulers set about annexing the independent states within Assyria during the mid- to late 3rd century, the last being Assur itself in the late 250s to early 260s. Christianity continued to spread, and many of the ethnically Assyrian churches that exist today are among the oldest in the world. For example, the Syriac Orthodox Church is purported to have been founded by St Peter himself in 67 AD.

Nevertheless, although predominantly Christian, a minority of Assyrians still held onto their ancient Mesopotamian religion until as late as the 10th or 11th century AD.[101][102] The Assyrians lived in a province known as Asuristan, and the region was on the frontier of the Byzantine and Sassanian empires.

The land was known as Asōristān (the Sassanid Persian name meaning "Land of the Assyrians") during this period, and became the birthplace of the distinct Church of the East (now split into the Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church) and a centre of the Syriac Orthodox Church, with a flourishing Syriac (Assyrian) Christian culture which exists there to this day. Temples were still being dedicated to the national god Ashur (as well as other Mesopotamian gods) in his home city, in Harran and elsewhere during the 4th and 5th centuries AD, indicating the ancient pre-Christian Assyrian identity was still extant to some degree.

During the Sasanian period, much of what had once been Babylonia in southern Mesopotamia was incorporated into Assyria, and in effect the whole of Mesopotamia came to be known as Asōristān. Parts of Assyria appear to have been semi independent as late as the latter part of the 4th century AD, with a king named Sennacherib II reputedly ruling the northern reaches in 370s AD.

Arab Islamic conquest (630–780)

Centuries of constant warfare between the Byzantine Empire and Sassanid Empire left both empires exhausted, which made both of them open to loss in a war against the Muslim Arab army, under the newfound Rashidun Caliphate. After the early Islamic conquests, Assyria was dissolved as an official administrative entity by an empire. Under Arab rule, Mesopotamia as a whole underwent a gradual process of further Arabisation and the beginning of Islamification, and the region saw a large influx of non-indigenous Arabs, Kurds, Iranian, and Turkic peoples.

However, the indigenous Assyrian population of northern Mesopotamia retained their language, religion, culture and identity.

Under the Arab Islamic empires, the Christian Assyrians were classed as dhimmis, who had certain restrictions imposed upon them. Assyrians were thus excluded from specific duties and occupations reserved for Muslims, they did not enjoy the same political rights as Muslims, their word was not equal to that of a Muslim in legal and civil matters without a Muslim witness, they were subject to payment of a special tax (jizyah) and they were banned from spreading their religion further in Muslim-ruled lands. However, personal matters such as marriage and divorce were governed by the cultural laws of the Assyrians.[103][104]

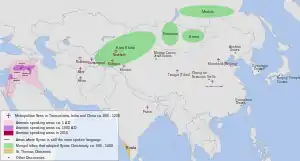

For those reasons, and even during the Sassanian period before Islamic rule, The Assyrian Church of the East formed a church structure that spread Nestorian Christianity to as far away as China, in order to proselytize away from Muslim-ruled regions in Iran and their homeland in Mesopotamia, with evidence of their massive church structure being the Nestorian Stele, an artifact found in China which documented over 100 years of Christian history in China from 600 to 781 AD.[105] Assyrian Christians maintained relations with fellow Christians in Armenia and Georgia throughout the Middle Ages. In the 12th century AD, Assyrian priests interceded on behalf of persecuted Arab Muslims in Georgia.[106]

Mongol Empire (1200–1300)

The first signs of trouble for the Assyrians started in the 13th century, when the Mongols first invaded the Near East after the fall of Baghdad in 1258 to Hulagu Khan.[107] Assyrians at first did very well under Mongol rule, as the Shamanist Mongols were sympathetic to them, with Assyrian priests having traveled to Mongolia centuries before. The Mongols in fact spent most of their time oppressing Muslims and Jews, outlawing the practice of circumcision and halal butchery, as they found them repulsive and violent.[108] Therefore, as one of the only groups in the region looked at in a good light, Assyrians were given special privileges and powers, with Hülegü even appointing an Assyrian Christian governor to Erbil (Arbela), and allowing the Syriac Orthodox Church to build a church there.[109]

However, the Mongol rulers in the Near East eventually converted to Islam. Sustained persecutions of Christians throughout the entirety of the Ilkhanate began in earnest in 1295 under the rule of Oïrat amir Nauruz, which affected the indigenous Christians greatly.[110] During the reign of the Ilkhan Öljeitü, the inhabitants of Erbil seized control of the citadel and much of the city in rebellion against the Muslims. In spring 1310, the Mongol Malik (governor) of the region attempted to seize it from them with the help of the Kurds and Arabs, but was defeated. After his defeat he decided to siege the city. The Assyrians held out for three months, but the citadel was at last taken by Ilkhanate troops and Arab, Turkic and Kurdish tribesmen on 1 July 1310. The defenders of the citadel fought to the last man, and many of the inhabitants of the lower town were subsequently massacred.

Regardless of these hardships, the Assyrian people remained numerically dominant in the north of Mesopotamia as late as the 14th century AD, and the city of Assur functioned as their religious and cultural capital. The seat of the Catholicos of the Church of the East was Seleucia-Ctesiphon, not Assur. In the mid-14th century the Muslim Turkish ruler Tamurlane conducted a religiously motivated massacre of the indigenous Christians, and entirely destroyed the vast Church of the East structure established throughout the Far East outside what had been the Sasanid Empire, with the exception of the St Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast in India, who numbered 4.2 million in the 2011 census of Kerala.[111] After Timur's campaign, ancient Assyria's cultural and religious capital of Assur fell entirely into ruins and part of it was used as a graveyard until the 1970s.[112]

Breakup of the Church of the East (1552–1830)

Around 100 years after the massacres by Timur, a religious schism known as the Schism of 1552 occurred among the Christians of northern Mesopotamia. A large number of followers of the Church of the East were dissatisfied with the leadership of the Church, at this point based in the Rabban Hormizd Monastery near Alqosh, and in particular with the system of hereditary succession of the patriarch. Three bishops elected the abbot of the monastery, Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa, as a rival patriarch. These did not have the rank of metropolitan bishop, which was required for appointing a patriarch and which was granted only to members of the patriarch's family. Sulaqa therefore went to Rome to be made a patriarch, entered into communion with the Catholic Church and was appointed "Patriarch of Mosul in Eastern Syria"[113] or "Patriarch of the Chaldean church of Mosul"[114] by Pope Julius III in 1553. He won support only in Diyarbakır (known also as Amid), where he set up his residence, and in Mardin. In 1555, he was killed by the Turkish authorities after being denounced by the traditionalist patriarch, but the metropolitans he had ordained elected a successor for him, initiating the Shimun line of patriarchs, all of whom took the name Shimun (Simon). The patriarchs of this line requested and obtained confirmation from Rome only until 1583. In 1672 they clearly broke off communion with Rome, but continued as a line of patriarchs independent from that at Alqosh, with their seat, from then on, at Qodchanis in the Hakkari mountains.[115] In a letter of 29 June 1653, 19 years before the Shimun line broke off relations with Rome, Shimun XI Eshuyow (1638–1656) called himself Patriarch of the Chaldeans. There is no record of a response from Rome confirming him as Catholic patriarch.[116]

Biblical Aramaic was until recently called Chaldaic or Chaldee,[117][118] and East Syrian Christians, whose liturgical language was and is a form of Aramaic, were called Chaldeans,[119] as an ethnic, not a religious term. Hormuzd Rassam (1826–1910) still applied the term "Chaldeans" no less to those not in communion with Rome than to the Catholic Chaldeans[120] and stated that "the present Chaldeans, with a few exceptions, speak the same dialect used in the Targum, and in some parts of Ezra and Daniel, which are called 'Chaldee'."[121]

Long before 1672, the Shimun line, as it "gradually returned to the traditional worship of the Church of the East, thereby losing the allegiance of the western regions",[122] moved from Turkish-controlled Diyarbakır to Urmia in Persia. The bishopric of Diyarbakır became subject to the Alqosh patriarch. Bishop Joseph of Diyarbakır converted to the Catholic faith in 1667 or 1668. In 1677, he obtained recognition from the Turkish authorities as invested with independent power in Diyarbakır and Mardin, and in 1681 he was recognized by Rome as "patriarch of the Chaldean nation deprived of its patriarch". Thus was instituted the Josephite line, a third line of patriarchs.[123]

In the Alqosh line, Eliya VII (1591–1617), Eliya VIII (1617–1660) and Eliya IX (1660–1700) contacted Rome at various times but without establishing union.[124] Union was achieved in 1771 under Eliya XI, who died in 1778. His successor Eliya XII, after sending his profession of faith to Rome and receiving confirmation as Catholic patriarch, adopted a traditionalist position in 1779. His opponents elected Yohannan Hormizd, a young nephew of Eliya XI, whom Eliya XI had intended to be his successor. Although Yohannan Hormizd won the support of most of the followers of the Alqosh patriarchate, Rome considered his election to be irregular and, instead of accepting him as patriarch, merely confirmed him as metropolitan of Mosul and patriarchal administrator. He was thus granted the powers and the insignia of a patriarch, but not the title. It made the same arrangement in Diyarbakır, appointing as patriarchal administrator Augustine Hindi, a nephew of Joseph IV, whom his uncle wished to be his successor as patriarch. There were thus two traditionalist patriarchates (the Eliya line and the Shimun) and, under administrators, two Catholic patriarchates (Diyarbakır and Alqosh/Mosul).

In 1804, Eliya XI died and had no traditionalist successor. Augustine Hindi died in 1827 and, in 1830, Rome appointed Yohannan Hormizd as patriarch of all the Catholics. The Shimun line, which had been the first to enter union with Rome, remained at the head of the traditionalist church that in 1976 adopted the name Assyrian Church of the East,[125][126][127] and that continued to be in the hands of the same family until the death in 1975 of Shimun XXI Eshai. At the same time, the originally traditionalist Alqosh line continues, without hereditary succession, at the head of the Chaldean Catholic Church.

Ottoman Empire (1900–1928)

After these splits, the Assyrians suffered a number of religiously and ethnically motivated massacres throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries,[129] such as the Massacres of Badr Khan which resulted in the massacre of over 10,000 Assyrians in the 1840s,[130] culminating in the large scale Hamidian massacres of unarmed men, women and children by Turks and Kurds in the 1890s at the hands of the Ottoman Empire and its associated (largely Kurdish and Arab) militias, which greatly reduced their numbers, particularly in southeastern Turkey where over 25,000 Assyrians were murdered.[131] The Adana massacre of 1909 largely aimed at Armenian Christians also accounted for the murder of some 1,500 Assyrians.[132]

The Assyrians suffered a further catastrophic series of events during World War I in the form of the religiously and ethnically motivated Assyrian Genocide at the hands of the Ottomans and their Kurdish and Arab allies from 1915 to 1918.[133][134][135][136] Some sources claim that the highest number of Assyrians killed during the period was 750,000, while a 1922 Assyrian assessment set it at 275,000. The Assyrian Genocide ran largely in conjunction with the similarly ethno-religiously motivated Armenian Genocide, Greek Genocide and Great Famine of Mount Lebanon.

In reaction against Ottoman cruelty, the Assyrians took up arms, and an Assyrian independence movement began during the turbulent events of World War I. For a time, the Assyrians fought successfully against overwhelming numbers, scoring a number of victories against the Ottomans and Kurds, and also hostile Arab and Iranian groups. However, due to the collapse of the Russian Empire—due to the Russian Revolution—and the similar collapse of the Armenian Defense, the Assyrians were left without allies. As a result, the Assyrians were vastly outnumbered, outgunned, surrounded, cut off, and without supplies. The only option they had was to flee the region into northwest Iran and fight their way, with around 50,000 civilians in tow, to British train lines going to Mandatory Iraq. The sizable Assyrian presence in south eastern Anatolia which had endured for over four millennia was thus reduced to no more than 15,000 by the end of World War I, and by 1924 many of those who remained were forcibly expelled in a display of ethnic cleansing by the Turkish government, with many leaving and later founding villages in the Sapna and Nahla valleys in the Dohuk Governorate of Iraq.

In 1920 the Assyrian settlements in Mindan and Baquba were attacked by Iraqi Arabs, but the Assyrian tribesmen displayed their military prowess by successfully defeating and driving off the Arab forces.[137] The Assyrians also sided with the British during the Iraqi revolt against the British.

The Assyrian Levies were founded by the British in 1922, with ancient Assyrian military rankings, such as Rab-shakeh, Rab-talia and Turtanu, being revived for the first time in millennia for this force. The Assyrians were prized by the British rulers for their fighting qualities, loyalty, bravery and discipline, and were used to help the British put down insurrections among the Arabs, Kurds and Turcoman, guard the borders with Iran and Turkey, and protect British military installations. During the 1920s Assyrian levies saw action in effectively defeating Arab and Kurdish forces during anti-British rebellions in Iraq.[137][138][139]

Simele Massacre and World War II (1930–1950)

After Iraq was granted independence by the British in 1933, the Assyrians suffered the Simele Massacre, where thousands of unarmed villagers (men, women and children) were slaughtered by joint Arab-Kurdish forces of the Iraqi Army. The massacres of civilians followed a clash between armed Assyrian tribesmen and the Iraqi army, where the Iraqi forces suffered a defeat after trying to disarm the Assyrians, whom they feared would attempt to secede from Iraq. Armed Assyrian Levies were prevented by the British from going to the aid of these civilians, and the British government then whitewashed the massacres at the League of Nations.

Despite these betrayals, the Assyrians were allied with the British during World War II, with eleven Assyrian companies seeing action in Palestine/Israel and another four serving in Greece, Cyprus and Albania. Assyrians played a major role in the victory over Arab-Iraqi forces at the Battle of Habbaniya and elsewhere in 1941, when the Iraqi government decided to join World War II on the side of Nazi Germany. The British presence in Iraq lasted until 1955, and Assyrian Levies remained attached to British forces until this time, after which they were disarmed and disbanded.

A further persecution of Assyrians took place in the Soviet Union in the late 1940s and early 1950s when thousands of Assyrians settled in Georgia, Armenia and southern Russia were forcibly deported from their homes in the dead of night by Stalin without warning or reason to Central Asia, with most being relocated to Kazakhstan, where a small minority still remain.[140]

Ba'athism (1966–2003)

The period from the 1940s through to 1963 was a period of respite for the Assyrians in northern Iraq and north east Syria. The regime of Iraqi President Kassim in particular saw the Assyrians accepted into mainstream society. Many urban Assyrians became successful businessmen, a number of Assyrians moved south to cities such as Baghdad, Basra and Nasiriyah to enhance their economic prospects, others were well represented in politics, the military, the arts and entertainment, Assyrian towns, villages, farmsteads and Assyrian quarters in major cities flourished undisturbed, and Assyrians came to excel and be over-represented in sports such as boxing, football, athletics, wrestling and swimming.

However, in 1963, the Ba'ath Party took power by force in Iraq, and came to power in Syria the same year. The Baathists, though secular, were Arab nationalists, and set about attempting to Arabize the many non-Arab peoples of Iraq and Syria, including the Assyrians. This policy included refusing to acknowledge the Assyrians as an ethnic group, banning the publication of written material in Eastern Aramaic, and banning its teaching in schools, together with an attempt to Arabize the ancient pre-Arab heritage of Mesopotamian civilisation.

The policies of the Baathists have also long been mirrored in Turkey, whose nationalist governments have refused to acknowledge the Assyrians as an ethnic group since the 1920s, and have attempted to Turkify the Assyrians by calling them "Semitic Turks" and forcing them to adopt Turkish names and language. In Iran, Assyrians continued to enjoy cultural, religious and ethnic rights, but due to the Islamic Revolution of 1979 their community has been diminished.

In the aftermath of the Iraq War of 2003, Assyrians became the targets of Islamist terrorist attacks and intimidation from both Sunni and Shia groups, as well as criminal kidnapping organisations; forcing many in southern and central Iraq to relocate to safer Assyrian regions in the north of the country or north east Syria.

Kurdistan Region (2005–present)

In 2017, the KRG replaced the Alqosh mayor, Faiz Abed Jahwareh with a KDP member, Lara Zara, and Assyrian protested in response.[142][143][144] The Iraqi Government ordered Lara Zara to vacate her post, and return the title of Mayor to Jahwareh.[145][146]

Syrian Civil War (2012–present)