Asashōryū Akinori

Asashōryū Akinori (Japanese: 朝青龍 明徳, born 27 September 1980,[2] as Dolgorsürengiin Dagvadorj, Mongolian Cyrillic: Долгорсүрэнгийн Дагвадорж; [tɔɮgɔrsʊːrengiːn tagw̜atɔrt͡ʃ]) is a Mongolian former professional sumo wrestler (rikishi). He was the 68th yokozuna in the history of the sport in Japan and became the first Mongolian to reach sumo's highest rank in January 2003. He was one of the most successful yokozuna ever.[3] In 2005, he became the first wrestler to win all six official tournaments (honbasho) in a single year. Over his entire career, he won 25 top division tournament championships, placing him fourth on the all-time list.

| Asashōryū Akinori | |

|---|---|

| 朝青龍 明徳 | |

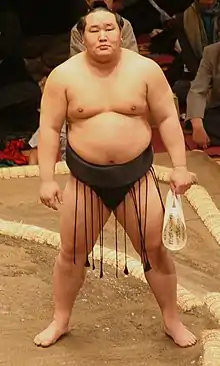

Asashōryū in the ring during the May 2009 sumo tournament | |

| Personal information | |

| Born | Dolgorsuren Dagvadorj 27 September 1980 Ulaanbaatar, Mongolian People's Republic |

| Height | 184 cm (6 ft 0 in) |

| Weight | 148 kg (326 lb; 23.3 st) |

| Web presence | website |

| Career | |

| Stable | Takasago |

| Record | 669–173–76 |

| Debut | January 1999 |

| Highest rank | Yokozuna (January 2003) |

| Retired | 6 February 2010[1] |

| Championships | 25 (Makuuchi) 1 (Makushita) 1 (Sandanme) 1 (Jonidan) |

| Special Prizes | Outstanding Performance (3) Fighting Spirit (3) |

| Gold Stars | 1 (Musashimaru) |

| * Up to date as of February 2015. | |

From 2004 until 2007, Asashōryū was sumo's sole yokozuna, and was criticized at times by the media and the Japan Sumo Association for not upholding the standards of behaviour expected of a holder of such a prestigious rank.[4] He became the first yokozuna in history to be suspended from competition in August 2007 when he participated in a charity football match in his home country despite having withdrawn from a regional sumo tour claiming injury.[5] After a career filled with a multitude of other controversies, both on and off the dohyō, his career was cut short when he retired from sumo in February 2010 after allegations that he assaulted a man outside a Tokyo nightclub.[6]

Early life and sumo background

Asashōryū comes from an ethnic Mongol family with a strong background in Mongolian wrestling, with his father and two of his elder brothers all achieving high ranks in the sport.[7] He also trained in judo in Mongolia.[8] He originally came to Japan as an exchange student, together with his friend, the future Asasekiryū, where they attended Meitoku Gijuku High School in Kōchi Prefecture. They both trained together at the sumo club there.[9]

Early career

He was recruited by the former ōzeki Asashio of the Wakamatsu stable (now Takasago stable), who gave him the shikona of Asashōryū, literally "morning blue dragon,"[10] Asa being a regular prefix in the Wakamatsu stable. The second part of the shikona, Akinori, is an alternative reading of Meitoku, the name of his high school.[11] He made his professional debut in January 1999. At that time, fellow Mongolians Kyokushūzan and Kyokutenhō were in the top division and stars back in their home country, but Asashōryū was quick to overtake them both. He attained elite sekitori status in September 2000 by winning promotion to the jūryō division, and reached the top makuuchi division just two tournaments later in January 2001. In May 2001, he made his san'yaku debut at komusubi rank and earned his first sanshō special prize, for Outstanding Performance.

In 2002, Asashōryū put together back-to-back records of 11–4, 11–4 and 12–3 and was promoted to sumo's second highest rank of ōzeki in July.[12] In November 2002, he took his first top division tournament championship (yūshō) with a 14–1 record. It took Asashōryū only 23 tournaments from his professional debut to win his first top division title, the fastest ever.[13] In January 2003, he won his second straight championship. Shortly after the tournament, Asashōryū was granted the title of yokozuna, the highest rank in sumo.[14] His promotion coincided with the retirement of the injury-plagued Takanohana, the last active Japanese born yokozuna until Kisenosato in January 2017.[15][16]

Yokozuna career

While his first tournament as yokozuna ended in a disappointing 10–5 record, Asashōryū won a further (twenty-three) tournaments. Combined with his two yūshō as an ōzeki, he had twenty-five career championships in the top division.[17] This puts him in fourth place on the all-time list, behind only Hakuhō, Taihō, and Chiyonofuji.[18]

2003

Asashōryū nominally shared the yokozuna rank with Musashimaru, but in fact his rival only fought a handful of bouts in 2003 due to injury.[19] The two did not meet in competition all year. Asashōryū won his first championship as a yokozuna in May 2003 and came back from an injury sustained in the July tournament to win his third title of the year in September.[20] Musashimaru announced his retirement in November, leaving Asashōryū as sumo's only yokozuna.[15]

2004

Asashōryū began 2004 with two consecutive perfect 15–0 tournament wins (zensho-yūshō) in January and March.[21] Nobody had attained a zensho-yūshō since 1996; yet Asashōryū went on to add three more such titles after 2004, for a career total of five. At that time only Taihō, with eight, and Chiyonofuji and Kitanoumi with seven, had recorded more 15–0 scores.[22] His unbeaten run continued into the first five days of the May 2004 tournament, giving him a winning streak of 35 bouts in total, the longest run since Chiyonofuji's 53 in 1988. Although he was then upset by maegashira Hokutōriki, he gained revenge by defeating Hokutōriki in a playoff on the final day to claim the championship.[23] On 27 November 2004, Asashōryū became the first wrestler to win five tournaments in a year since Chiyonofuji achieved the feat in 1986, and won his ninth Emperor's Cup.[24] Asashōryū's below average 9–6 score in the September basho of 2004, the only one he did not win, was attributed in part to the official ceremony for his marriage, which was held in August 2004 (although he had actually married in December 2002). The hectic social round that inevitably follows Japanese weddings affected his pre-tournament preparations, as it prevented him from doing any training.[21]

2005

He continued to dominate sumo in 2005, becoming the first wrestler ever to win all six honbasho (sumo tournaments) in the same year. The great yokozuna Taihō achieved the feat of six consecutive tournament victories twice, but never in a calendar year.[25] Asashōryū lost only six bouts all year (0–1–0–2–2–1). One of those rare losses came on 11 September 2005, at the start of the September tournament when he dropped his first Day 1 bout during his tenure as yokozuna. On 26 November 2005, a visibly emotional Asashōryū wept after winning his eighty-third bout of the year, (surpassing Kitanoumi's record set in 1978) and clinching the tournament at the same time.[26] The six championships of 2005 (including two more 15–0 wins in January and May) combined with his victory from the final tournament of 2004, meant Asashōryū became the first man in sumo history to win seven consecutive tournament championships.[26]

2006

Asashōryū's consecutive basho streak came to an end in January 2006, when ōzeki Tochiazuma took the first tournament championship of the year.[27] Asashōryū's performance in January was a surprisingly poor 11–4 but he successfully rebounded by winning the March tournament.[28] However, his six losses in those tournaments matched his loss total for all of 2005. In the May tournament, he sustained an injury to the ligaments in his elbow on the second day falling out of the ring in a surprising loss to Wakanosato and was visibly slow to rise from the ground.[29] He was absent from the tournament the next day and later released a statement confirming he was withdrawing from the tournament.[30] Doctors told him he would not be able to compete for two months, which meant he would miss the July tournament as well.[31] However, Asashōryū was ready by the start of the July tournament and won with a 14–1 record. In the following tournament, Asashōryū won his eighteenth career title with a 13–2 record.[32] He also won the final tournament of 2006 for his nineteenth career title, the fifth he has won with a perfect 15–0 record.[33]

2007

In January 2007, Asashōryū posted a 14–1 record, his fourth straight championship since returning from injury, and became the fifth man to win twenty career championships.[34] In March, he dropped his first two bouts but then won thirteen in a row for a 13–2 score. However, this was not enough to win the title—he lost a playoff for the first time in his career, to fellow Mongolian Hakuhō.[35] In May he turned in a below par 10–5 record, losing to all four ōzeki and maegashira Aminishiki (although he appeared to be carrying an injury). Hakuhō won this tournament as well and was promoted to yokozuna immediately afterwards.[36] Asashōryū had been the sole yokozuna for a total of 21 tournaments since the retirement of Musashimaru in November 2003 – the longest period of time in sumo history. In July he lost to Aminishiki once again on the opening day but rallied to win the next fourteen bouts, taking his 21st title with a 14–1 record.[37] He was suspended by the Sumo Association from the next two tournaments (see below).

2008

Asashōryū returned to tournaments in January 2008. On the final day, he faced Hakuhō in a battle of 13–1 yokozuna, but was defeated, giving him a final record of 13–2.[38] In March the two yokozuna faced off for the title again on the last day, marking only the fifth time in the last 30 years that two yokozuna have contested the championship on the last day of two consecutive tournaments.[39] In this rematch, Asashōryū was the victor, winning his 22nd title, thus equalling Takanohana's haul of tournament championships.[40]

In the May tournament he lost to Kisenosato on the opening day. He injured his back in this match and subsequent losses to Kotoōshū (the eventual winner of the tournament) and Chiyotaikai put him out of contention.[41]

Asashōryū got off to a bad start in the July tournament by losing to Toyonoshima on the first day. After a second loss to maegashira Tochinonada on day five, he pulled out of the tournament on the sixth day citing pain in his elbow.[42] The September tournament unfolded in a similarly poor fashion. After compiling a lacklustre 5–4 record through the first nine days, Asashōryū forfeited his tenth-day match to maegashira Gōeidō and withdrew. He had elbow pain, and presented a medical certificate.[43]

He returned to Mongolia in October 2008, staying until shortly before the tournament in Kyushu in November, which he did not enter. He stated that he would not withdraw for a third time partway through a tourney, and suggested that he would retire if his comeback proved unsuccessful.[44]

2009

The January 2009 honbasho, Asashōryū's first full tournament since May 2008, was a remarkable success. He won his first fourteen matches, losing only on the last day to Hakuhō. He then won the resulting playoff to earn his 23rd championship and pass Takanohana on the all-time list to become the fourth ever wrestler to have won 23 tournaments[45] (the other three being Taihō, Kitanoumi and Chiyonofuji). His victory came exactly twenty years after yokozuna Hokutoumi also returned from three tournaments out to win the championship with a 14–1 record. Sumo Association head Musashigawa described Asashōryū's comeback as "amazing." Ticket sales and television ratings showed a marked increase as his winning run continued.[46] After his playoff win Asashōryū announced to the crowd, "Everyone, thank you very much. Really. I am back."[46]

In the following tournament in March he went undefeated for the first nine days but then lost to three of the five ōzeki over the next five days, putting him out of contention for the championship. He also lost his final day match to Hakuhō to finish at 11–4. In the May tournament he lost early to Aminishiki, then won ten in a row before falling to Harumafuji on Day 14. He again lost to Hakuhō, on the final day, finishing at 12–3.[47]

Asashōryū returned to Mongolia after the May tournament to receive treatment for a bruised chest suffered in his defeat to Harumafuji. In June he received the Hero of Labour Award from outgoing Mongolian President Nambaryn Enkhbayar, the highest government award in Mongolia and equivalent to the Japanese People's Honour Award.[48] He performed poorly in the July tournament with a 10–5 record, his worst finish in just over two years.

He damaged ligaments in his right knee during a regional tour of Akita in August 2009 (the first time he had injured his knee), hampering his preparations for the September tournament.[49] Despite this, he won his first 14 matches, before finally losing to Hakuhō, leaving both wrestlers at 14–1. Asashōryū would win the resulting playoff to win his 24th yūshō, tying him with Kitanoumi for third on the all-time yūshō list. The triumph took place on his 29th birthday.[50] He finished on 11–4 in the Kyushu tournament in November, losing his last four matches.[51]

Controversy

Match-fixing speculation and lawsuits

In January 2007, Shūkan Gendai, a weekly tabloid magazine, reported that Asashōryū had paid opponents about ¥800,000 ($10,000) per fight to allow him to win the previous November 2006 tournament with a perfect score. Asashōryū denied these claims in court on 3 October 2008, during the first ever court appearance by a yokozuna.[53] He appeared as part of a lawsuit brought by the Japan Sumo Association and about 30 other wrestlers seeking around ¥660 million ($8.12 million) from Shūkan Gendai's publisher, Kodansha Ltd.[54] He said the allegations were "complete lies ... I am very sad and disgusted."[53] Also appearing in court, in defence of the magazine, was former wrestler Itai, who had made similar allegations of bout-fixing in 2000 regarding his own career. Itai suggested that Asashōryū's win over Chiyotaikai in the November 2006 tournament was an example of a fixed match.[55]

On 26 March 2009, the Tokyo District Court ordered Kodansha, the publisher of the magazine, and Yorimasa Takeda, the freelance writer of the articles, to pay ¥42.90 million ($437,000) in damages, believed to be the highest award for libel damages against a magazine in Japanese history.[56] Chief judge Yasushi Nakamura stated that the reporting was "slipshod in the extreme."[56]

Suspension

After his tournament victory in July 2007, Asashōryū decided to skip the regional summer tour of Tōhoku and Hokkaidō beginning on 3 August because of injury. The medical forms submitted to the Japan Sumo Association indicated that injuries to his left elbow and a stress fracture in his lower back would require six weeks of rest to heal.[57] However, he was then seen on television participating in a football match for charity with Hidetoshi Nakata in his homeland of Mongolia. He was reported to have done so at the request of the Japanese Foreign Ministry and the Mongolian government.[58] However, the suggestion that he had exaggerated the extent of his injuries to avoid his duties on the exhibition tour caused a media storm.

Asashōryū was ordered to return to Japan and on 1 August 2007, the Sumo Association suspended him for the upcoming September tournament as well as the next one in November, the first time in the sport's history that an active yokozuna has been suspended from a main tournament. They also announced that Asashōryū and his stablemaster Takasago would have their salaries cut by 30% for the next four months.[5] He was also instructed to restrict his movements to his home, his stable, and the hospital.[59] Isenoumi, a Director of the Sumo Association, called Asashōryū's behaviour "a serious indiscretion. Given that a yokozuna should act as a good example for the other wrestlers, this punishment for his action is appropriate."[60] It was the most severe punishment ever imposed on a yokozuna since the Grand Tournament system was adopted over 80 years ago.[61] Asashōryū responded by saying he would get his injuries treated and prepare for the winter regional tour and the January 2008 tournament.[62] However, his stablemaster reported that Asashōryū was finding the severity of the punishment difficult to deal with,[63] and two doctors from the Sumo Association diagnosed him as suffering from acute stress disorder, and then dissociative disorder.[64] On 28 August he was allowed to return to Mongolia for treatment.[65] After recuperation and onsen treatment, he returned to Japan on 30 November 2007, apologising for his actions at a press conference.[66]

Assault allegations and subsequent retirement

During the January 2010 tournament, a tabloid magazine claimed Asashōryū punched his personal manager after getting drunk during a night out in downtown Nishiazabu.[52] After the tournament Asashōryū was reprimanded by Japan Sumo Association (JSA) head Musashigawa, and he apologised once again for his behaviour.[67] However, it subsequently emerged that it was not his manager but a restaurant employee who was attacked, reportedly sustaining a broken nose. The man did not file a report with the police,[68] and on 31 January 2010, Asashōryū told the authorities that he had reached a settlement with him.[69] Despite this, the police did not rule out the possibility of questioning Asashōryū about the assault.[70]

Subsequently, on 4 February 2010, he announced his decision to retire, after discussing the matter at a meeting with the Board of Directors of the Sumo Association.[71] He stated, "I feel heavy responsibility as a yokozuna that I have caused trouble to so many people. I am the only person who can put an end to it all. I think it's my destiny that I retire like this."[71] Asashōryū did not comment directly on the brawl, except to say that what actually happened was "quite different" to media reports.[72] "I decided to step down to bring this to a closure."[72]

Asashōryū referred to criticism for not showing hinkaku (dignity) as a yokozuna. "Everybody talks about dignity, but when I went into the ring, I felt fierce like a devil."[73] Asked what his most memorable bout was, he chose his first win over Musashimaru in May 2001, with his parents watching him.[74]

JSA Chief Director Musashigawa revealed that directors were debating on that day whether to punish Asashōryū. "He felt compelled to resign for misconduct that was inexcusable, and the board accepted. I want to apologize to all of the fans and to the person injured in the incident."[75] The Yokozuna Deliberation Council had recommended his retirement, and would have pressed for his dismissal if he had not chosen to go.[76]

In Mongolia, there was anger at the news. One high-ranking Mongolian official accused the Sumo Association of using the incident as an excuse to get rid of Asashōryū before he could reach Taihō's 32 tournament victories. "I feel that they did not want him to break the record for most titles. This behavior is unjust. The Mongolian people disapprove."[77] The Zuunii Medee newspaper called for sumo broadcasts in Mongolia to be suspended.[78] Reacting to the tense mood among the Mongolian public, a spokesman at the Foreign Ministry of Mongolia issued a statement that the "resignation of Asashōryū will have no influence to the friendship between Mongolian and Japanese citizens." and he requested people stay calm.[79] Reaction in Japan was more mixed, with some of the public saying the yokozuna had to go while others said they would miss him.[80] News media compared his case with earlier yokozuna Maedayama who was forced to resign in 1949 after dropping out of a tournament claiming illness but subsequently photographed at a baseball game.[81] Both his stablemaster and the Sumo Association received criticism for their handling of this incident and Asashōryū in general.[80]

As Asashōryū never obtained Japanese citizenship, he was not eligible to stay in the sumo world as an oyakata, or coach.[78] He was, however, entitled to a formal retirement ceremony, or danpatsu-shiki, at the Ryōgoku Kokugikan[82] and was also given a retirement allowance by the Sumo Association, believed to be around ¥120 million ($1.34 million).[83]

Asashōryū gave a press conference in Mongolia on 11 March, and denied committing any "act of violence," but said he did not regret his decision to retire.[84] He claimed it was "an undeniable fact" that there were people within the Sumo Association "trying to push me out of sumo" and that he could have gone on to win 30 or more tournament titles.[84] Asked about rumours that he would enter mixed martial arts, he replied, "I haven't really thought about what to do next."[85] He refused to take any questions from Japanese reporters.[85]

He was questioned voluntarily by investigators in May, and reportedly said that his hand "may have struck" the man, but he denied assault.[86] In July police reported him to the public prosecutors.[86] His former stablemaster Takasago said if Asashōryū was indicted then his retirement ceremony may be cancelled.[87] However, the event went ahead as planned on 3 October, with around 380 dignitaries taking turns in snipping his oichiomage or topknot before Takasago made the final cut.[88] Asashōryū said to the 10,000 fans at the Kokugikan, "In another life as a Japanese, I would like to become a yokozuna with Japanese spirit... I want to show everyone that I can become a better person."[88]

Other events

Asashōryū received criticism from Sumo Association officials and the media throughout his yokozuna career for various other infractions of the strict code of conduct expected of top sumo wrestlers, both on the dohyō and off it. His breaches of etiquette during tournament bouts ranged from merely accepting the prize money with the wrong hand,[89] and raising his arms in victory after clinching the championship,[90] to giving opponents an extra shove after the bout was already over (such as Hakuhō in May 2008),[91] and appealing to judges to overturn the referee's decision.[89] In July 2003, he pulled on fellow Mongolian Kyokushūzan's mage (traditional Japanese top knot) during their bout on day five of the tournament, resulting in an immediate hansoku-make, or disqualification.[92] He was the first yokozuna to be disqualified from a bout. They reportedly brawled in the communal bath afterwards, and Asashōryū was also accused of breaking the wing mirror of Kyokushūzan's car.[93][94] Some Japanese fans called on him to "go back to Mongolia" after this incident.[93] He also had an uneasy relationship with his stablemaster Takasago.[89] In July 2004, he apologized after a row with Takasago over his wedding arrangements resulted in him being seen drunk in public and damaging stable property,[95] and his tendency to return to Mongolia without informing his stablemaster led to embarrassments like being unable to attend the funeral of Takasago stable's previous head coach Fujinishiki in December 2003.[96] He was also sometimes seen in public in a business suit or in casual dress instead of the traditional kimono that wrestlers are expected to wear.[93]

Post-sumo career

Immediately after his retirement from sumo there was speculation that Asashōryū would switch to mixed martial arts, and he was reported to be forming an MMA camp for Mongolian athletes.[97] However, instead he became a businessman. Asashōryū had held business interests in Mongolia whilst still active in sumo, launching the family holding company as early as 2003.[98] Based in Ulaanbaatar and investing exclusively inside Mongolia, the company has assets in banking, real estate and mining.[98]

In 2012, his wealth was estimated to be between US$50 and 75 million.[98] He is also active in philanthropy, establishing the Asashoryu Foundation which has supported the Mongolian Olympic team, given scholarships to Mongolian college students studying in Mongolia and Japan, and donated English-language textbooks to schools.[98]

In 2007, Asashōryū bought the National Circus Palace (a 2,000-seat circus building in Ulaanbaatar[99]) through his company, "Asa Consulting". Since then the palace has been renamed to "Asa Tsirk".[100]

He became a member of the Mongolian Democratic Party in May 2013.[101]

He appears in the 2017 Chinese kung-fu film Gong Shou Dao.

Fighting style

Asashōryū was a relative lightweight early in his career, weighing just 129 kg (284 lb) in 2001, and relied on speed and technique to compete against often much heavier opponents. However, he gradually put on weight and by 2010 was about 148 kg (326 lb), right on average. In his later career he tended to confront his opponents head on with the intention of out-muscling them. In training, he was reported to do multiple repetitions of biceps curls with 30-kilogram (66 lb) dumb-bells, and whilst in the gym with NHK commentator Hiro Morita in 2008 he reportedly bench pressed 200 kg (441 lb). He had an intense approach to keiko (training), and some high-profile wrestlers avoided training with him, fearing injury.[102]

Asashōryū's favoured techniques according to his Sumo Association profile were migi-yotsu/yori, a left hand outside, right hand inside grip on his opponent's mawashi (belt), and tsuppari, a series of rapid thrusts to the chest.[103] His most common winning kimarite throughout his career were yorikiri (force out), oshidashi (push out), uwatenage (outer arm throw), shitatenage (inner arm throw) and tsukidashi (thrust out).[104] He used 45 different kimarite in his career, a wider range than most wrestlers.[104] In July 2009, he defeated Harumafuji by an "inner thigh throw" or yaguranage,[105] a technique not seen in the top division since 1975. His trademark, however, was tsuriotoshi, or "lifting body slam",[8] a feat of tremendous strength normally only used on much smaller and weaker opponents. In 2004, Asashōryū twice dumped the 158-kilogram (348 lb) Kotomitsuki using this technique.[104]

Family

Asashōryū's brothers were active in other combat sports: Dolgorsürengiin Sumyaabazar was a mixed martial arts fighter, and Dolgorsürengiin Serjbüdee, a professional wrestler, competed in New Japan Pro Wrestling under the name Blue Wolf (after the Mongolian Blue Wolf legend). All Dolgorsüren brothers have strong backgrounds in Mongolian wrestling.

Asashōryū first met his first wife in high school when they were both 15 years old.[106] They married in 2002 and their reception in Tokyo in 2004 was broadcast live on TV.[107] They divorced in 2009 having been separated for several years.[108] He has a son and a daughter.[98] In July 2020 he announced via Twitter that he was getting married, uploading a picture of himself with his presumed fiancée.[107]

Asashōryū's nephew Byambasuren became a professional sumo wrestler in November 2017, joining the Tatsunami stable. His shikona is Hōshōryū, and he made his first tournament appearance in January 2018.[109] He reached the top division in September 2020.

Career record

| Year in sumo | January Hatsu basho, Tokyo |

March Haru basho, Osaka |

May Natsu basho, Tokyo |

July Nagoya basho, Nagoya |

September Aki basho, Tokyo |

November Kyūshū basho, Fukuoka |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | (Maezumo) | East Jonokuchi #34 6–1 |

Jonidan #85 7–0–PP Champion |

West Sandanme #75 7–0 Champion |

Makushita #53 6–1–PPPP |

East Makushita #27 6–1 |

| 2000 | West Makushita #12 3–4 |

West Makushita #19 5–2 |

West Makushita #9 6–1 |

West Makushita #2 7–0 Champion |

East Jūryō #7 9–6 |

West Jūryō #3 11–4 |

| 2001 | West Maegashira #12 9–6 |

East Maegashira #6 9–6 |

West Komusubi #1 8–7 O |

East Komusubi #1 7–8 |

West Maegashira #1 10–5 F★ |

East Komusubi #1 10–5 F |

| 2002 | West Sekiwake #1 8–7 |

West Sekiwake #1 11–4 O |

West Sekiwake #1 11–4 F |

East Sekiwake #1 12–3 O |

East Ōzeki #3 10–5 |

East Ōzeki #2 14–1 |

| 2003 | East Ōzeki #1 14–1 |

West Yokozuna #1 10–5 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 5–5–5 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 12–3 |

| 2004 | East Yokozuna #1 15–0 |

East Yokozuna #1 15–0 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2–P |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 9–6 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

| 2005 | East Yokozuna #1 15–0 |

East Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

East Yokozuna #1 15–0 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2–P |

East Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

| 2006 | East Yokozuna #1 11–4 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2–P |

East Yokozuna #1 1–2–12 |

East Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 15–0 |

| 2007 | East Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2–P |

East Yokozuna #1 10–5 |

East Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

East Yokozuna #1 Suspended 0–0–15 |

West Yokozuna #1 Suspended 0–0–15 |

| 2008 | West Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

West Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 11–4 |

East Yokozuna #1 3–3–9 |

West Yokozuna #1 5–5–5 |

West Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

| 2009 | West Yokozuna #1 14–1–P |

East Yokozuna #1 11–4 |

West Yokozuna #1 12–3 |

West Yokozuna #1 10–5 |

West Yokozuna #1 14–1–P |

East Yokozuna #1 11–4 |

| 2010 | West Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 Retired – |

x | x | x | x |

| Record given as win-loss-absent Top Division Champion Top Division Runner-up Retired Lower Divisions Sanshō key: F=Fighting spirit; O=Outstanding performance; T=Technique Also shown: ★=Kinboshi(s); P=Playoff(s) | ||||||

See also

References

- 横綱朝青龍が引退を表明「世間を騒がせた」 Archived 5 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "朝青龍". Jiji Press (in Japanese). 25 January 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Kuroda, Joe (February 2006). "A Shot At the Impossible-Yokozuna Comparison Through The Ages". sumofanmag.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- Fogarty, Philippa (18 September 2007). "Sumo world hit by giant troubles". BBC News. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- "Asashoryu suspended from next two grand tournaments". Japan Times. 2 August 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Mongolian sumo champion Asashoryu retires after brawl". BBC. 4 February 2010. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- Frederick, Jim (28 April 2003). "Dolgorsuren Dagvadorj: Possessing the strength to lift an entire nation". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- "Asashoryu resumes serious practice". UB Post. 8 November 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- Wallace, Bruce (18 February 2005). "He's put tradition on its ear". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- "Sumo champ Asashoryu loved and hated even in defeat". AFP. 27 January 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- Gunning, John (3 February 2021). "Interesting facts about sumo's 13 living former yokozuna". Japan Times. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Mongolian wrestler promoted to ozeki". Japan Times. 25 July 2002. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- "Asashoryu claims title, continues to set records". Japan Times. 23 November 2002. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- "Asashoryu gets yokozuna rank". Japan Times. 30 January 2003. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- "Maru:Sumo needs Japanese yokozuna". Japan Times. 30 January 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- "Kisenato becomes first japanese born yokozuna almost two decades". Japan Times. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Asashoryu Akinori Rikishi Information". Sumo Reference. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Hakuho steals Asa's thunder on final day". Japan Times. 25 January 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- "Musashimaru retires". Japan Times. 16 November 2003. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu bags Emperor's Cu". Japan Times. 21 September 2003. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "2004 was the year of Asashoryu in sumo". Japan Times. 1 January 2005. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- "Query result". Sumo Reference. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu nails Emperor's Cup". Japan Times. 24 May 2004. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu wins Kyushu Basho". Japan Times. 28 November 2004. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "All yusho winners". Sumo Reference. Archived from the original on 19 January 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu claims record 7th straight Emperor's Cup". Japan Times. 27 November 2005. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- "Tochiazuma captures third Emperor's Cup title". Japan Times. 23 January 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu beats Hakuho for 16th Cup". Japan Times. 27 March 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu hurts arm in surprise loss". Japan Times. 9 May 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Hakuho stays unbeaten in Summer Basho". Japan Times. 10 May 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Hakuho tied for lead as Asashoryu withdraws". Taipei Times. 10 May 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- "Asashoryu reigns again". Japan Times. 24 September 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asa runs table in Fukuoka". Japan Times. 27 November 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu secures Emperor's Cup title". Japan Times. 21 January 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Hakuho stuns Asa to win tourney". Japan Times. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Undefeated Hakuho dominates Asashoryu". Japan Times. 28 May 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu wins battle of yokozuna, 21st title". Japan Times. 23 July 2007. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- "Hakuho wins dramatic final". Japan Times. 28 January 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Buckton, Mark (25 March 2008). "Hakusho Part II raises more questions marks". Japan Times. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Ganbayer, G. (27 March 2008). "Asashoryu Wins 22nd Emperor's Cup". UB Post. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- "Kotooshu keeps lead after yokozuna sweep". Japan Times. 23 May 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Asashoryu storms out of Sumo tournament". Agence France-Presse. 18 July 2008. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- "Hakuho retains lead; Asashoryu withdraws". Japan Times. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- "Asa goes home; may miss tourney". Japan Times. 7 October 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Buckton, Mark (27 January 2009). "Amazing comeback for Asashoryu at Hatsu basho '09". Japan Times. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- "Asashoryu dazzles fans in comeback win". AFP. 25 January 2009. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- "Harumafuji topples Hakuho in playoff". The Japan Times. 25 May 2009. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- "Asa receives award in Mongolia". Japan Times. 13 June 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- "Asa uncertain for Autumn Basho". Japan Times. 23 August 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- "Asashoryu beats Hakuho in playoff to win 24th sumo title". Japan Today. 27 September 2009. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- "Hakuho stays undefeated". Japan Times. 30 November 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- "Asa clinches 25th Emperor's Cup". Japan Times. 24 January 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- "Asashoryu goes to court to deny bout-fixing". AFP. 3 October 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "Sumo champion Asashoryu in court contest over 'fight-fixing'". The Times. London. 4 October 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Alford, Peter (4 October 2008). "Ex-sumo wrestler claims bout-fixing is rife". The Australian. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Publisher fined for "fixed" sumo series". Asahi Shimbun. 27 March 2009. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- "Men attempting to extort Kyokushuzan arrested". Japan Times. 26 July 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- "Soccer match draws JSA's ire". Japan Times. 27 July 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "A grand champion is rebuked". Japan Times. 4 August 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Sumo association suspends Asashōryū from two tourneys". International Herald Tribune. 1 August 2007. Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- Fogarty, Philippa (18 September 2007). "Sumo world hit by giant troubles". BBC News. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- "Reaction to Asashoryu's punishment". Sumo Talk. 2 August 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Takasago-oyakata holds press conference; Asashoryu taking medication". Sumo Talk. 2 August 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- Parry, Richard Lloyd (22 August 2007). "Mongolia declares sumo war over shame of star in a Rooney shirt". The Times. London. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- "Asashoryu heading home for treatment". Japan Times Online. 29 August 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- "Asashoryu apologizes for causing trouble". Japan Times Online. 1 December 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- "Asashoryu warned over conduct". Japan Times. 26 January 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- "Asashoryu's drunken attack on acquaintance left him with broken nose". Mainichi Daily News. 28 January 2010. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- "Asashoryu reports settlement with alleged assault victim". Mainichi Daily News. 1 February 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- "Police may question Asashoryu". Japan Times. 1 February 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "Sumo's 'bad boy' Asashoryu to retire". AFP. 4 February 2010. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- Hayashi, Yuka (4 February 2010). "Sumo Grand Champion to Retire After Brawl". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 1 March 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "Sumo wrestler retires after drunken scuffle". Fairfax New Zealand Limited. 5 February 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- Dickie, Mure (4 February 2010). "Bad-boy sumo champion bows out". FT.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "Asashoryu ends stormy career". Japan Times. 4 February 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "End of the line for Asashoryu". Japan Times. 6 February 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Top Mongolian officials erupt over Asashoryu resignation". Mainichi Daily News. 5 February 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Mongolian press ridicules JSA". Japan Times. 7 February 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- "Top 朝青龍引退 モンゴル外務省、国民に「冷静に」". Asahi Shimbun. 5 February 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- "Reaction mixed over Asashoryu's retirement". Mainichi Daily News. 5 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- Hayashi, Yuka (5 February 2010). "In Blow to Sumo, Champion Retires". Wall St Journal, reprinted in Student News Magazine. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "Conspiracy Fallout Over Asashoryu's Shocking Retirement". UB Post. 9 February 2010. Archived from the original on 13 February 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- "Asashoryu to receive 120 million yen retirement allowance". Mainichi Daily News. 11 February 2010. Archived from the original on 13 February 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- "Sumo – Mongolian 'bete noir' says he was forced to quit". Reuters India. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- "Sumo: Asashoryu denies alleged drunken rampage, undecided on future". Kyodo News. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- "Police report Asashoryu to public prosecutors over assault in Tokyo". Mainichi Daily News. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2010.

- "No retirement ceremony for Asashoryu if indicted: ex-boss". Japan Today. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- "Asashoryu bows out at topknot ceremony". Japan Times. 4 October 2010. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- Perran, Thierry (August 2007). "The yokozuna Asashoryu suspended for two tournaments". Le Monde du Sumo. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- Ryall, Julian (6 October 2009). "Sumo champion Asashoryu outrages sport with celebration". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- "Kotooshu claims Emperor's Cup; yokozuna clash highlights finale". Japan Times. 26 May 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- youtube.com

- McCurry, Justin (11 February 2004). "Big In Japan". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- "Sumo-"Tsar" Roho throws tantrum after defeat". Mail & Guardian Online. 16 July 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- Ryall, Julian (30 July 2004). "Sumo master ready for a fall after rampage". The Scotsman. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- McNeill, David (7 August 2007). "The sumo champion, the sickie and the story that shook Japan". The Independent. London. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- "Disgraced Sumo Legend Asashoryu Forms MMA Camp, Will Work With Sengoku Raiden Championships". Bloody Elbow. 22 July 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "An Ex-Sumo Wrestler Returns To Mongolia". Forbes Asia. 24 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "Mongolian National Circus". circus.mn/en/. 1 January 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- iKon.mn, Д. Эрдэнэцэн (6 March 2014). "АСА цирк ТӨРД буцаж магадгүй нь". ikon.mn. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "Yokozuna Asashoryu becomes Democratic Party member". Infomongolia.com. 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "Smallish Asashoryu having super-size effect on sumo". Honolulu Advertiser. 5 June 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- "Asashoryu – Favorite Grip/Techniques". Japan Sumo Association. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- Doitsuyama (13 May 2009). "Asashoryu bouts by kimarite". Sumo Reference.

- "Hakuho takes sole lead with finish line in sight". Japan Times Online. 25 July 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- Klein, Barbara Ann (February 2006). "Sumo 101 – the Wife behind the Yokozuna". Sumo Fan Magazine. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- "Ex-sumo yokozuna Asashoryu announces marriage with Twitter snap". The Mainichi. 16 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Sumo champ Asashoryu had spring divorce". Japan Times. 7 July 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "元朝青龍のおい豊昇龍「青」でなく「昇」とした理由". Nikkan Sports. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "Asashoryu Akinori Rikishi Information". Sumo Reference. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

External links

- Asashōryū Akinori's official biography (English) at the Grand Sumo Homepage

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asashōryū Akinori. |

| Preceded by Musashimaru Kōyō |

68th Yokozuna 2003–2010 |

Succeeded by Hakuhō Shō | ||

| Yokozuna is not a successive rank, and more than one wrestler can hold the title at once | ||||