Asthall barrow

Asthall barrow is a high-status Anglo-Saxon burial mound from the seventh century AD. It is located in Asthall, Oxfordshire, and was excavated in 1923 and 1924.

.jpg.webp)

Location

Asthall barrow is located along the strip of the A40 connecting the towns of Witney and Burford; it is immediately north of the A40 where it connects to Burford road, and just south of the byroad leading off Burford to Asthall and Swinbrook.[1][2] The barrow is prominently located.[3] It sits by Akeman Street where the Roman road crossed the River Windrush, the site of a onetime Roman settlement.[3][4] It has expansive views, and overlooks the Thames Valley from Lechlade to Wytham Hill.[1] To the north it looks out at Leafield barrow; to the south appears Faringdon Hill and beyond it the Berkshire Downs at White Horse Hill, while to the southeast Sinodun Hill near Dorchester appears, with the Chilterns in the distance.[1] The barrow gives its name to surrounding structures, such as Barrow Plaintation, Barrow Farmhouse, and Asthall Barrow Roundabout.[2]

Architecture

The barrow stands 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) high, and is about 55 ft (17 m) in diameter.[5] It was recorded as 8 ft 6 in (2.6 m) high around 1907,[6] but, in 1923, as 12 ft (3.7 m) high.[7] It is surrounded by a 4 ft 6 in (1.37 m) high dry stone retaining wall.[5][7] Once covered in trees including beeches and firs, likely planted in the nineteenth century,[5][7] the barrow is now topped by a single, prominent, sycamore; the remaining growth was removed during conservation work in 2017 or 2018.[8] The presence of Romano–British grey wares in the barrow's soil, like the downward sloping surrounding land, suggests that the barrow may have been constructed by scraping up the surrounding topsoil.[5] The land around the barrow is cultivated up to its edges, and in 1992 was planted with barley crops.[9]

Originally the barrow probably stood larger; in 1923 an elliptical section surrounding the southwest circumference was recorded as approximately 4 in (10 cm) higher than the field, suggesting that it was once a part of the barrow.[5][10] That the barrow's finds were not in the centre of its present dimensions also suggests that its original dimensions were somewhat different.[5] Slippage of the barrow's soil may also help explain the changed dimensions, and the recorded reduction in height over time.[5]

Grave goods

The barrow contained a large assemblage of items, of a quality indicating the high-status nature of the burial.[11] There were at least seven vessels: three pottery, two hand-made jars, a Merovingian bottle, and a small silver bowl or cup.[12] Fragments of foil, five of which were stamped with zoomorphic interlace patterns, suggest the burial of a decorated drinking horn, and a pear-shaped mount was both patterned and gilded.[13] Other items appear to have been made of bone, and were likely pieces from a gaming set.[14] The finds were donated to the Ashmolean, where they were given the accession numbers 1923.769–782, and 1949.297.[15]

| Accession | Image | Category | Description | Material | Dimensions | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923.769 | .png.webp) | Vessel | Merovingian wheel-made bottle | Pottery | 247mm (h); 168mm (d) | [16][17][18][19] | |

| 1923.770 | .png.webp) | Vessel | Hand-made pot | 125mm (h); 110mm (d) | [20][21] | ||

| 1923.771 | .png.webp) | Vessel | Hand-made pot | 115mm (h); 127mm (d) | [22][23] | ||

| 1923.778 | Vessel | Bowl or cup | Silver | 13+ heavily oxidised fragments, including rim and body pieces | |||

| 1923.776 | .png.webp) | Vessel | Byzantine bowl | Cast copper alloy | 4+ fragments, including rim, hinge-loop, and foot-ring | [24] | |

| 1923.779 | Vessel | Bowl or cauldron | Copper alloy | Unburnt sheet-metal body fragment; rim fragment from same or similar vessel | [24][25] | ||

| 1923.779 | Vessel | Fittings for drinking horn(s), bottle(s), or cup(s) | Copper alloy | Sheet metal including repoussé foils decorated in Salin Style II and/or with billeted border, fluted binding strips with dome-headed rivets and U-sectioned rim-edge bindings | |||

| 1923.779 | Vessel | Vessel | Copper alloy | 3–3.5mm (d) | Several fragments of sheet metal with one edge rolled into a narrow tube | ||

| 1923.774 | .png.webp) | Strap fittings | Strap end | Cast copper alloy | 41mm (l); 19mm (w) | Mineralized textile on back | [26][27] |

| 1923.775 | Strap fittings | Looped strap tab | Cast copper alloy | 35mm (l); 11mm (w); 13mm (d) | |||

| 1923.777 | .png.webp) | Strap fittings | Hinged strap attachment | Cast copper alloy | 22mm (l); 14.5mm (w) | Includes iron hinge-pin | [28][29] |

| 1923.779 | Strap fittings | Looped strap mount | Cast copper alloy | 12.5mm (l); 13mm (w) | [30] | ||

| 1923.775 | .png.webp) | Strap fittings | Openwork swivel suspension fitting | Cast copper alloy | Openwork cuboid, 12.5mm (l), 9mm (w); swivel loop, 20mm (l); looped strap tab, 19.5mm (l), 6mm (w) | [31][32] | |

| 1923.779 | Strap fittings | Disc-headed rivets | 8mm (d); 5mm (l) | 3 fragments. Heads decorated with concentric rings | [33] | ||

| 1923.773 | .png.webp) | Strap fittings | Pear-shaped mount | Cast copper alloy; gilt | 47mm (l) (reconstructed) | Salin Style II on front; two cast-in-one disc-ended rivets on back | [34] |

| 1923.782 | Gaming set | Counters | Bone | 30mm (d); 4mm (h) | 26 fragments, plano-convex | ||

| 1949.297 | Gaming set | Die | Antler | 14mm cube | |||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Rectangular-headed rivet | Silver | Head, 6.7mm (l), 5mm (w); shank, 7mm (l) | |||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Disc | Silver | 17mm (d); 4.3mm (th) | Bevelled edge | ||

| 1923.779 | .png.webp) | Unassignable items | "Silver" strap mount | Copper alloy | 19mm (l) (extant); 6mm (w) | Cast. Two rivets on back corroded green; front gray. | [35][36] |

| 1923.779 | .png.webp) | Unassignable items | Two crescentic studs | Copper alloy | 15mm (d) | Decorated with punched triangles. Rivet on back. | [37][38] |

| 1923.779 | .png.webp) | Unassignable items | Sunken-field stud | Copper alloy | 10.5mm (d); 2.5mm (h); shank 8mm (l) | Cast. Dome-headed rivet passes through centre of sunken field and bent flat on underside. | [37][39] |

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Disc-headed rivet | Copper alloy | 6.5mm (d); shank 5.5mm (l) (extant) | Plain | ||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Dome-headed rivet pin | Copper alloy | 3.3mm (d); 9.5mm (l); shank 8.5mm (l) | |||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Relief-decorated disc or ring | Copper alloy | 15mm (l); 14mm (w) | Cast. Fragment with thickened edge and hint of curvature. Northed ridge border and Salin Style I zoomorphic field. | ||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Plain disc | Copper alloy | 23mm (d) | Plain. | ||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | Unidentified fragments | Copper alloy | Constitutes the majority of the material catalogued under 1923.779. Includes sandwiched foil fragments, pieces covered with/incorporating corrosion products, charcoal and soil, generally thicker than the foils, and globules of melted metal. May come from the copper-alloy vessels or unassignable items. | |||

| 1923.779 | Unassignable items | "Nails" | Iron | 11.5–22mm (l) | 4 fragments | ||

| 1923.780 | Unassignable items | Inlays? | Iron | 4–5mm, 15mm (w) | 55 fragments with flat rectangular or slightly plano-convex section, most with plain outer surface and grooved or cross-grooved inner surface, some also with grooved outer surface, and two with cross-hatched edges | ||

| 1923.781 | Unassignable items | "Rods" | Iron | 46mm (l) (max); 6.5mm (d) (max) | 11 fragments, slightly curved and tapered | ||

| n/a | Cremated bone | Four finger bones; fragments of jaw; roots of canine and lower molar | Human bone | ||||

| n/a | Cremated bone | Left tibia; right lateral cuneiform; sesamoid; likely metatarsal | horse bone | ||||

| n/a | Cremated bone | Astragalus; possible tail vertebrae; skull fragments | sheep bone | ||||

| 1923.772 | From barrow make-up | Romano–British pottery sherds | Worn residual material | [10] |

Excavation

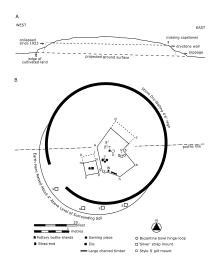

The barrow was excavated in August 1923, and again in 1924, by George Bowles, the brother in law of the second Baron Redesdale, who owned the land.[40][15] Permission to excavate had been unsuccessfully sought in 1872, on behalf of George Rolleston.[41] The 1923 excavation was overseen by Bowles, although actually carried out by a Tom Arnold and five helpers.[42] Bowles was also aided by Edward Thurlow Leeds, then assistant keeper at the University of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum; Leeds offered suggestions, visited the site, and published the main discoveries.[40][15] He published the 1923 excavation along with an excavation plot by Bowls in The Antiquaries Journal in April 1924, and briefly discussed the 1924 excavation 15 years later in a chapter of A History of Oxfordshire.[43][44][15] Both excavations are also plotted, probably by Leeds, on a piece of blue linen held by the Ashmolean.[15]

Bowles dug an irregular, seven-cornered polygonal trench in 1923, and in 1924 added a rectangular trench to its side, along with four 18-inch-square trenches in the area of the raised surrounding soil.[5] He began by sinking a shaft 12 feet square and 12 feet deep; to this he added several subsequent extensions, each to the level of the field or below.[7][5] He labeled the corners A–H on his plot, omitting the F.[45][46] Bowles determined the barrow to be undisturbed and to consist of earth mixed with stones, along with the occasional sherd of Romano–British pottery.[7][5][note 1] The surface level was coated in yellowish clay, perhaps brought up from the River Windrush nearby.[48][49] This faded away toward corner B, Bowles noted, but was prevalent around corner G, the southern limit of the excavation.[50] Atop the clay Bowles found an abundance of charcoal and ashes, six inches thick in places (such as at point V on his plot), and forming only a thin covering elsewhere.[50][49] Bowles also recorded a large charred timber, between points G and H.[50][49]

Conservation

The Asthall barrow was designated a scheduled monument on 16 May 1934.[2] Historic England, which maintains the list of such monuments, noted that the barrow "is one of the best preserved examples of a type of burial mound of which there are about ten examples in West Oxfordshire", and that "[d]espite partial excavation and recent animal burrowing it will contain archaeological and environmental evidence relating to its construction and the landscape in which it was built."[2] Historic England added that the "survival of part of its original drystone retaining wall is an unusual feature", but that regardless, "[a]s a rare monument class all positively identified examples are considered worthy of preservation."[2]

In 2009, the barrow was added to Historic England's "Heritage At Risk Register", a project intended to identify and protect historic sites threatened by neglect, decay, or development.[51] The 2009 list was the first to include scheduled monuments that are archaeological sites; previous iterations had included only listed buildings, structural scheduled monuments, registered battlefields, and protected wreck sites.[52] The barrow remained on the at-risk register through 2017.[53][54] From 2009 to 2014, the its condition was described as "declining" with "generally unsatisfactory with major localised problems," and its principal vulnerability was given as scrub and tree growth.[55][56][57][58][59][60] Its principal vulnerability was changed to collapse by 2015,[61] although by 2016 its condition was upgraded to "improving."[62] In 2017, the barrow's final year on the register, its principal vulnerability was given as extensive rabbit burrowing.[63] The barrow was listed as "saved" and removed from the register the following year, following removal of trees and scrub, and work to exclude rabbits; the large sycamore tree atop the barrow was left in place.[8] The work was done in partnership with the owners, and voluntary wardens from the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[8]

Notes

- Bowles, whose daughter described him as a "gentleman amateur", may not be an authoritative voice for the idea that the barrow was hitherto intact.[47] Likewise, one of several explanations for the wide and seemingly random distribution of objects within is that the barrow had previously been opened.[12] Absent a re-excavation, Bowles's claim is thus uncertain.[47]

References

- Leeds 1924, p. 113.

- Historic England Asthall Barrow.

- Williams 2006, p. 202.

- Cassey and Co. 1868, p. 15.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 98.

- Potts 1907, p. 345.

- Leeds 1924, p. 114.

- Historic England 2018.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 98–99.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 114–115.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 112.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 101.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 103–104.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 105.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 96.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 122–123, figs. 8–9.

- Fox 1924.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 101–102, 106, 110, 113, 124, fig. 16C.

- Ashmolean Merovingian bottle.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 121–122, fig. 7 (left).

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 101, 106, 124, fig. 16A.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 121–122, fig. 7 (right).

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 101, 124, fig. 16B.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 119–120, fig. 5K.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 101–104, 124, fig. 18A, pl. 3.3.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 120–121, fig. 5D.

- Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18c.

- Leeds 1924, p. 120, fig. 5G.

- Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18b.

- Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18a.

- Leeds 1924, p. 120, fig. 5B.

- Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18d.

- Dickinson 1976c, fig. 18e.

- Leeds 1924, p. 121, figs. 5C, 6.

- Leeds 1924, p. 119, fig. 5F.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 105, 124, pl. 4.14.

- Leeds 1924, p. 120, fig. 5E.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 126, pl. 4.16.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 105, 126, pl. 4.17.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 113–114.

- Leeds 1924, p. 114 n.2.

- Leeds 1924, p. 117.

- Leeds 1924.

- Leeds 1939.

- Leeds 1924, p. 115.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 98–00.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, pp. 96, 101.

- Leeds 1924, pp. 115–116.

- Dickinson & Speake 1992, p. 100.

- Leeds 1924, p. 116.

- Parfitt & Whimster 2009, pp. 3, 67.

- Parfitt & Whimster 2009, p. 3.

- Heritage at Risk 2017.

- Heritage at Risk 2018.

- Parfitt & Whimster 2009, p. 67.

- Heritage at Risk 2010, p. 64.

- Heritage at Risk 2011, p. 70.

- Heritage at Risk 2012, p. 74.

- Heritage at Risk 2013, p. 67.

- Heritage at Risk 2014, p. 73.

- Heritage at Risk 2015, p. 68.

- Heritage at Risk 2016, p. 64.

- Heritage at Risk 2017, p. 63.

Bibliography

- "Asthall". History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Berkshire and Oxfordshire, with an Excellent Map of Each County. London: Edward Cassey and Co. 1868. pp. 14–15.

- "Asthall Barrow - an Anglo-Saxon Burial". Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017.

- "Bottle". Ashmolean Museum. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Colvin, Christina; Cragoe, Carol; Ortenberg, Veronica; Peberdy, Robert B.; Selwyn, Nesta & Williamson, Elizabeth (2006). "Asthall: Introduction". In Townley, Simon (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. XV. London: Institute of Historical Research. pp. 37–48.

- Colvin, Christina; Cragoe, Carol; Ortenberg, Veronica; Peberdy, Robert B.; Selwyn, Nesta & Williamson, Elizabeth (2006). "Asthall: Economic History". In Townley, Simon (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. XV. London: Institute of Historical Research. pp. 55–64.

- Davies, Wendy & Vierck, Hayo (December 1974). "The Contexts of Tribal Hidage: Social Aggregates and Settlement Patterns". Frühmittelalterliche Studien. 2: 223–302. doi:10.1515/9783110242072.223.

- Dickinson, Tania M. (October 1976). The Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites of the Upper Thames Region, and their Bearing on the History of Wessex, Circa AD 400–700 (Ph.D.). I. University of Oxford.

- Dickinson, Tania M. (October 1976). The Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites of the Upper Thames Region, and their Bearing on the History of Wessex, Circa AD 400–700 (Ph.D.). II. University of Oxford.

- Dickinson, Tania M. (October 1976). The Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites of the Upper Thames Region, and their Bearing on the History of Wessex, Circa AD 400–700 (Ph.D.). III. University of Oxford.

- Dickinson, Tania M. & Speake, George (1992). "The Seventh-Century Cremation Burial in Asthall Barrow, Oxfordshire: A Reassessment" (PDF). In Carver, Martin (ed.). The Age of Sutton Hoo: The seventh century in north-western Europe. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 95–130. ISBN 0-85115-330-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2019.

- Fox, Cyril (October 1924). "A Jug of the Anglo-Saxon Period". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. IV (4): 371–374.

- "Heritage at Risk 2018". Historic England. 8 November 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Historic England. "Asthall Barrow: an Anglo-Saxon burial mound 100m SSW of Barrow Farm (1008414)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Leeds, E. Thurlow (April 1924). "An Anglo-Saxon Cremation-burial of the Seventh Century in Asthall Barrow, Oxfordshire". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. IV (2): 113–126.

- Leeds, E. Thurlow (1939). "Anglo-Saxon Remains". In Salzman, Louis Francis (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. I. London: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. 346–372.

- MacGregor, Arthur & Bolick, Ellen (1993). "A Summary Catalogue of the Anglo-Saxon Collections (Non-Ferrous Metals)". British Archaeological Reports. 230. ISBN 978-0860547518.

- Manning, Percy (April 1898). "Notes on the Archæology of Oxford and its Neighbourhood". The Berks, Bucks & Oxon Archæological Journal. Berkshire Archaeological Society. 4 (1): 9–10.

- Meaney, Audrey (1964). A Gazetteer of Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Parfitt, Clare & Whimster, Rowan, eds. (June 2009). Heritage at Risk Register 2009: South East. London: English Heritage.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2010: South East. London: English Heritage. July 2010.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2011: South East. London: English Heritage. October 2011.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2012: South East. London: English Heritage. September 2012.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2013: South East. London: English Heritage. October 2013.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2014: South East. London: English Heritage. October 2014.

- Heritage at Risk: South East Register 2015. London: English Heritage. October 2015.

- Heritage at Risk: South East Register 2016. London: English Heritage. October 2016.

- Heritage at Risk: South East Register 2017. London: English Heritage. October 2017.

- Heritage at Risk: South East Register 2018. London: English Heritage. November 2018.

- Heritage at Risk Register 2010: South East. London: English Heritage. July 2010.

- Pickering, A. J. (April 1932). "A Hanging-bowl from Leicestershire". The Antiquaries Journal. Society of Antiquaries of London. XII (2): 174–175. doi:10.1017/S0003581500047235.

- Potts, William (1907). "Ancient Earthworks". In Page, William (ed.). A History of Oxfordshire. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. II. London: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. 303–349.

- "Site Name: Asthall". Oxfordshire's Historic Archives. Ashmolean Museum. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- Timby, Jane (January 1993). A40 Witney Bypass to Sturt Farm Improvement: Archaeological Survey (PDF). Cirencester: Cotswold Archaeological Trust.

- Williams, Howard (2006). Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain. Cambridge Studies in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511489594. ISBN 978-0-511-48959-4.

- Windle, Bertram (July 1901). "A Tentative List of Objects of Prehistoric and Early Historic Interest in the Counties of Berks, Bucks and Oxford". The Berks, Bucks & Oxon Archæological Journal. Berkshire Archaeological Society. 7 (2): 43–47.