Atlanta compromise

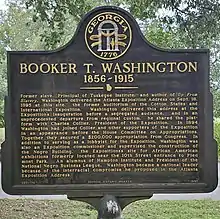

The Atlanta compromise was an agreement struck in 1895 between Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute, other African-American leaders, and Southern white leaders.[1][2] It was first supported[3] and later opposed by W. E. B. Du Bois and other African-American leaders such as Martin Luther King.

The agreement was that Southern blacks would work and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic education and due process in law.[4][5] Blacks would not focus their demands on equality, integration, or justice, and Northern whites would fund black educational charities.[6][7]

Social impact

The compromise was announced on September 18, 1895 at the Atlanta Exposition Speech. The primary architect of the compromise, on behalf of the African-Americans, was Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute. Supporters of Washington and the Atlanta compromise were termed the "Tuskegee Machine".

The agreement was never written down. Essential elements of the agreement were that blacks would not ask for the right to vote, they would not retaliate against racist behavior, they would tolerate segregation and discrimination, that they would receive free basic education, education would be limited to vocational or industrial training (for instance as teachers or nurses), liberal arts education would be prohibited (for instance, college education in the classics, humanities, art, or literature).[8][9]

After the turn of the 20th century, other black leaders, most notably W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter – (a group Du Bois would call The Talented Tenth), took issue with the compromise, instead believing that African-Americans should engage in a struggle for civil rights. W. E. B. Du Bois coined the term "Atlanta Compromise" to denote Booker's earlier agreement. The term "accommodationism" is also used to denote the essence of the Atlanta compromise.

After Washington's death in 1915, supporters of the Atlanta compromise gradually shifted their support to civil rights activism, until the Civil Rights Movement commenced in the 1950s.

Du Bois believed that the Atlanta Massacre of 1906 was a consequence of the Atlanta Compromise[10] and observer William Archer referred to it as "a grimly ironic comment on Mr. Washington's speech."[11]

See also

Footnotes

- (Lewis 2009, pp. 180–181)

- (Croce 2001, pp. 1–3)

- Harlan, Louis R. (1972), Booker T. Washington: The Making of a Black Leader, 1856–1901, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 225,

Let me heartily congratulate you upon your phenomenal success at Atlanta – it was a word fitly spoken.

- (Lewis 2009, pp. 180–181))

- (Croce 2001, pp. 1–3)

- (Lewis 2009, pp. 180–181)

- (Croce 2001, pp. 1–3)

- (Lewis 2009, pp. 180–181))

- (Croce 2001, pp. 1–3)

- (Croce 2001, p. 178)

- Archer, William, ed. (1910). "Four Possibilities: II. The Atlanta Compromise". Through Afro-America: an English reading of the race problem. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. p. 209. hdl:2027/uc1.31175010654476. OCLC 867981446.

At best, indeed, the Southern kindliness of feeling towards the individual Negro subsisted only so long as he 'knew his place' and kept it; and the very process of education and elevation on which Mr. Washington relies renders the Negro ever less willing to keep the place the Southern white man assigned him. In the North, too, while the dislike of the individual has greatly increased, the theoretic fondness for the race has very perceptibly cooled. Altogether, the tendency of events since 1895 has not been at all in the direction of the Atlanta Compromise. The Atlanta riot of eleven years later was a grimly ironic comment on Mr. Washington's speech.

References

- Croce, Paul (2001). W. E. B. Du Bois: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29665-9.

- Harlan, Louis R. (1986), Booker T. Washington: The Wizard of Tuskegee, 1901-1915, Oxford University Press, pp. 71–120.

- Harlan, Louis R. (2006), "A Black Leader in the Age of Jim Crow", in The Racial Politics of Booker T. Washington, Donald Cunnigen, Rutledge M. Dennis, Myrtle Gonza Glascoe (eds), Emerald Group Publishing, p. 26.

- Lewis, David (2009). W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography 1868-1963. Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0805088052.

- Logan, Rayford Whittingham, The Betrayal of the Negro, from Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson, Da Capo Press, 1997, pp. 275–313.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Atlanta compromise |

- Transcript of Booker T. Washington's Atlanta Exposition Address (1895). Plain text copy here.

- The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow, a PBS exposé regarding Washington in 1895.

- Stories of Atlanta - Speaking from the Heart