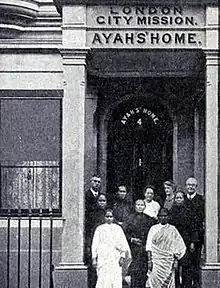

Ayahs' Home

The Ayahs' Home, London, provided accommodation for Indian ayahs and Chinese amahs (nannies) at the turn of the 20th century who were "ill-treated, dismissed from service or simply abandoned" with no return passage to their home country.[4] The Home also operated like an employment exchange to help ayahs find placements with families returning to India. It was the only institution of its type in Britain with a named building.

| |

| Purpose | Home for abandoned or destitute ayahs |

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Affiliations | London City Mission |

In 2020 the former site on King Edward Road, Hackney was shortlisted for a Blue Plaque following an application by local resident Farhanah Mamoojee. Following this, Farhanah organised an event on 7th March, 2020 at Hackney Museum, supported by the Mayor of Hackney, to draw further attention to the hidden history of the Ayahs and Amahs, which consisted of a panel discussion with academic Rozina Visram, as well as a poetry workshop and spoken word performance by The Yoniverse Collective, [extensive coverage was featured in The Hackney Post]. The event gained national and international press via BBC World Service, The Guardian, ITV News London and Business Insider (Mumbai) The history of the Ayahs, and the Ayahs’ Home, is gaining popularity and further coverage via the Ayahs’ Home Instagram page.

Background

Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the East India Company was abolished and its powers transferred to the British Crown under the Government of India Act 1858. This resulted in a large number of British families travelling between the two countries.[4] Many of these families employed local servants as they were cheaper than British staff. Among them were ayahs, the most highly prized being the sophisticated "Madrassi ayahs".[5] Some ayahs were experienced travellers and advertised their services in newspapers.[6] Travelling ayahs were seen as "honest, clean, capable nurses and made good sailors".[4]

The British public were captivated by the picturesque ayahs shown in paintings and books. The ayah would accompany the British family back to England, either on the seasonal trips to escape the Indian summer or on retirement of the colonial official. These journeys were more frequent after 1869 with the introduction of steam-powered ships and regular passenger services such as those provided by P&O. The journey was shortened by 4,500 miles after the Suez Canal opened in 1869, with the effect that up to 140 travelling ayahs visited England every year with their employing families, memsahibs and children. Some may have had a sense of adventure, but they were vulnerable to the whims of their erstwhile employers. Without official contracts or guarantees for return passages, some ayahs then had their employment terminated or were abandoned, forcing them to live in squalor or to beg. Others found alternative employment to pay for return journeys or stayed in Britain.[4][5][7]

"Lady with Ayah," 1860s

"Lady with Ayah," 1860s Ayahs with their charges, 1880s

Ayahs with their charges, 1880s.jpg.webp) Ayah with children

Ayah with children

Origins

The exact date and method of establishment of the Ayahs' Home is unclear.[8] Evidence from the India Office gives a foundation date of 1825;[9] however, it has also been said to have been founded in 1891 by Mr and Mrs Rogers at 6 Jewry Street, Aldgate.[4] It appears to have been closed prior to 1891 due to administrative inadequacies,[9] but, in response to the lobbying of a committee of white British women, the foreigners' branch committee of the London City Mission (LCM) took it over and prevented its permanent closure.[4] Around 1900, the Home moved to 26 King Edward Road, Mare Street, Hackney, and in 1921, requiring more space, it moved to the larger 4 King Edward Road.[4] The new home was opened by Lady Chelmsford, wife of Frederic Thesiger, 1st Viscount Chelmsford, the former Viceroy of India.[8][9]

Early years

Regarded as a "symbol of empire" and a "home from home", around 100 ayahs stayed at the Home each year.[4] The residents were mainly nurse-maids from India and other countries including China, Java and Malaya.[4] Socio-political changes created variations in numbers, with a higher occupancy during the Indian summer when many British families returned to escape the heat. The home was almost unoccupied from November to March. It was busier during the First World War when sea travel was banned for women, with a resulting increase in the number of stranded ayahs.[8] After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, 223 Ayahs were recorded at the Home as families rushed back to England at the first opportunity. The number of occupants was less during the depression of the 1930s.[4] The length of stay varied from weeks to months.[5]

Despite the lack of any testimonies from the ayahs, it is known that they were typically older women, used to childcare responsibilities and able to fit into both the English and Indian worlds.[4] Life in the Home was an amalgamation of oriental and western tradition, with Indian food, the playing of pachis, embroidery and outings to places of interest such as Westminster Abbey, the Houses of Parliament and Buckingham Palace.[4]

The Home generated income by the resale of the ayah's ticket, public donations, fundraising events and the sale of handwork done by the ayahs. A deficit in finances by 1917, when the war prolonged occupancy, led the Home's administrator to apply to the India Office for assistance. Initially hesitant, by 1928 the office was making an annual contribution to the Home.[9]

Matron's testimony

In 1910, Mrs Dunn, the matron of the Home, gave evidence to the Committee on Distressed Colonial and Indian Subjects of the India Office. Dunn described how the system depended on the ayah's return ticket. The employer who released the ayah from duties once in Britain typically purchased the ayah's return ticket, which was transferred to the Home. The ticket was then "sold" to a family wanting the ayah's services; the Home used the money from the sale to pay for the ayah's accommodation until she departed.[8] According to her evidence, the Home had been established by a committee of women who had realised there should be a shelter for abandoned ayahs in England.[5][8]

Among the evidence that was given by Mrs Dunn and also recorded in correspondence between the Home and the India Office was of an ayah who was brought to England from Bombay by a British woman in 1908, who, in the usual manner, released her to Thomas Cook and Son in order to transfer her employment. Re-employed by the Drummond family of Edinburgh who had pledged her return to India, she was abandoned at London's King's Cross Station, leaving her with one pound after two weeks work. The ayah arrived at the Thomas Cook office, which then directed her to the Home. Not in the custom of taking in destitute women, Mrs Dunn successfully obtained compensation from the India Office.[9][10]

Missionary activity

The Home was a converting station for missionaries to introduce the ayahs to Christianity. "Foreigners' Fetes" were frequently organised by the Foreigner's Branch Committee of the LCM, which was supported by Christian missionaries.[8] Religious services were held daily, hymns were taught and religious "chats in the bedroom" which the matron felt were "productive of much good", were part of daily life at the Home.[4] This all principally stemmed from the perception of ayahs as "child-like".[4]

Demonstrating a "domestic ideal and moral framework", the parlour of the Home was depicted in Alec Robert's Living London article "Missionary London", with a group of women looking busy sewing and reading.[11] Expressing Christian charity for the benefit of the ayahs' welfare and the British empire, the Home encouraged the ayahs to show gratitude and loyalty.[4]

Joseph Salter was the missionary responsible for the Home. He was the missionary to the Strangers' Home for Asiatics on behalf of London City Mission[12] and experienced from working with lascars and spoke several Indian languages.[9][13]

References

- Sims, George R. (1901) Living London.

- London City Mission, 1900.

- 1948 Ordnance Survey map, Digimap, 8 March 2018. (subscription required)

- Visram, Rozina. (2002). Asians In Britain: 400 Years of History. London: Pluto Press. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-0-7453-1378-8.

- "Our Migration Story: The Making of Britain". www.ourmigrationstory.org.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Four women" by Caroline Bressey in Paisley, Fiona; Reid, Kirsty, eds. (2014). Critical Perspectives on Colonialism: Writing the Empire from Below. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-136-27461-9.

- Homes for Indian nannies. British Library. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Ayahs' Home. Making Britain, Open University. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- "Ayah, Caregiver to Anglo-Indian Children, c. 1750–1947" by Suzanne Conway in Simon Sleight & Shirleene Robinson. (Eds.) (2016). Children, Childhood and Youth in the British World. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 52–55. ISBN 978-1-137-48941-8.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Untold Lives: An abandoned ayah". British Library. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "Viewing the Early Twentieth-Century Institutional Interior Through the Pages of Living London" by Fiona Fisher in Jane Hamlett, Lesley Hoskins, & Rebecca Preston. (Eds.) (2016). Residential Institutions in Britain, 1725–1970: Inmates and Environments. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-317-32025-8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Joseph Salter. Making Britain, Open University. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Mathur, Saloni. (2007). India by Design: Colonial History and Cultural Display. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-520-23417-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ayahs' Home. |

- The Ayahs' Home in Hackney. Andrew Whitehead's Blog

● Satyasikha Chakraborty, "Nurses of Our Ocean Highways": The Precarious Metropolitan Lives of Colonial South Asian Ayahs Journal of Women's History, Vol.22, No.2 (2020)

● Olivia Robinson, Travelling Ayahs of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Global Networks and Mobilization of Agency History Workshop Journal, Vol.86 (2018)