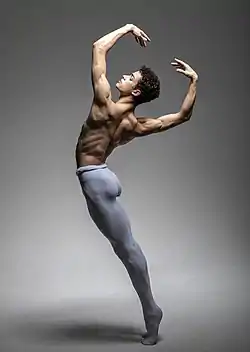

Ballet dancer

A ballet dancer (Italian: ballerina [balleˈriːna] fem.; ballerino [balleˈriːno] masc.) is a person who practices the art of classical ballet. Both females and males can practice ballet; however, dancers have a strict hierarchy and strict gender roles. They rely on years of extensive training and proper technique to become a part of professional companies. Ballet dancers are at a high risk of injury due to the demanding technique of ballet.[1]

Training and technique

Ballet dancers typically begin training between the ages of 6 and 8 (for females) and 5 and 7 (for male dancers) if they desire to perform professionally. Training does not end when ballet dancers are hired by a professional company. They must attend ballet class six days a week to keep themselves fit and aware. Ballet is a strict form of art, and the dancer must be very athletic and flexible.

Ballet dancers begin their classes at the barre, a wooden beam that runs along the walls of the ballet studio. Dancers use the barre to support themselves during exercises. Barre work is designed to warm up the body and stretch muscles to prepare for center work, where they execute exercises without the barre. Center work in the middle of the room starts out with slower exercises, gradually leading up to faster exercises and larger movements. Ballet dancers finish center work practicing big leaps across the floor, which is called grande allegro.

After center work, females present exercises on pointe, and on their toes, supported by special pointe shoes. Males practice jumps and turns. They may practice partner work together.[1]

Injuries

Ballet dancers are susceptible to injury because they are constantly putting strain and stress on their bodies and their feet. A ballet dancer's goal is to make physically demanding choreography appear effortless. Ballet dancers increase their risk of injury if they start training earlier than the age of ten. However, many ballet dancers do start on the average age of 6 to 8 years old.[2]

The upper body of a ballet dancer is prone to injury because choreography and class exercises requires them to exert energy into contorting their backs and hips. Back bends cause the back to pinch, making the spine vulnerable to injuries such as spasms and pinched nerves. Extending the legs and holding them in the air while turned out causes damage to the hips. Such damage includes strains, fatigue fractures, and bone density loss.[3]

Injuries are common in ballet dancers because ballet consists of putting the body in unnatural positions. One such position is first position, in which the heels are placed together as the toes point outward, rotating, or "turning out" the legs. If First Position is done incorrectly it can cause knee problems, however, when done correctly (turning out with the hips rather than the knees) it should increase flexibility and reduce pressure on the knees. Meniscal tears and dislocations can happen at the knees when positioned incorrectly because it is easy to let the knees slide forward while turned out in first position.

Ballet dancer's feet are prone to fractures and other damage. Landing incorrectly (not through the foot, with knees bent) from jumps and working in pointe shoes may increase risk of broken bones and weakened ankles where care and attention is not taken by a conscientious teacher and student. Tendonitis is common in female ballet dancers because pointe work is strenuous on their ankles. Landing from jumps incorrectly may also lead to shin splints, in which the muscle separates from the bone.[2]

Class time is used to correct any habits that could lead to injury. If the ballet dancer is properly trained, the dancer will decrease their risk of injury. Some ballet dancers also turn to stretching or other methods of cross training, like Pilates, Yoga, non impact cardio, and swimming. This, outside cross training, attempts to minimize the risk of bodily damage by increasing strength, exercise diversity, and stamina. Nevertheless, injuries are a common occurrence in performances. Most injuries do not show up until later in a ballet dancer's life, after years of continuous strain.[1]

Gendered titles

Traditionally, gender-specific titles are used for ballet dancers. In French, a male ballet dancer is referred to as a danseur and a female as a danseuse. In Italian, a ballerina is a female who typically holds a principal title within a ballet company; the title for equally ranked males is ballerino. In Italian, the common term for a male dancer is danzatore and a female dancer is a danzatrice.

These terms are rarely used in English. Since ballerino is not used in English, it does not enjoy the same connotation as ballerina. A regular male dancer in Italy is called a ballerino. In the English speaking world, boys or men who dance classical ballet are usually referred to as (male) ballet dancers. Often "ballerino" is used in English-based countries as slang.

As late as the 1950s a ballerina was the principal female dancer of a ballet company who was also very accomplished in the international world of ballet, especially beyond her own company; female dancers who danced ballet were then called danseuses or simply ballet dancers. Ballerina was a critical accolade bestowed on relatively few female dancers, somewhat similar to the title diva in opera. The male version of this term is danseur noble (French). Since the 1960s, however, the term has lost this honorific aspect and is applied generally to women who are ballet dancers.[4]

In the original Italian, the terms ballerino (a male dancer, usually in ballet) and ballerina do not imply the accomplished and critically acclaimed dancers once meant by the terms ballerina and danseur noble when used in English. Rather, they simply mean one who dances ballet. Italian terms that do convey an accomplished female ballet dancer are prima ballerina and prima ballerina assoluta (the French word étoile is used in this sense at the Scala ballet company in Milan but has a different meaning at the Paris Opera Ballet.).

The term ballerina is sometimes used to denote a well-trained and highly accomplished female classical ballet dancer. In such cases, it is a critical accolade that signifies exceptional talent and accomplishment.

Hierarchic titles

Many use the term ballerina incorrectly, often using it to describe any female ballet student or dancer. Ballerina was once a rank given only to the most exceptional female soloists.

Women

More or less, depending on the source, the rankings for women—from highest to lowest—used to be:

- Prima ballerina assoluta (Italy)

- Prima ballerina, premier sujet or première danseuse

- Sujet

- Coryphée

- Corps de ballet

Men

For men, the ranks were:

- Premier danseur noble

- Premier danseur

- Danseur

- Sujet

- Coryphée

- Corps de ballet

- Ballerino

Today

Ballet companies continue to rank their dancers in hierarchical fashion, although most have adopted a gender neutral classification system, and very few recognise a single leading dancer above all other company members. In most large companies, there are usually several leading dancers of each gender, titled principal dancer or étoile to reflect their seniority, and more often, their status within the company. The most common rankings (in English) are:

- Principal dancer

- Soloist (or First soloist)

- Demi-soloist (or Second soloist)

- Corps de ballet

- Apprentice

Dancers who are identified as a guest artist are usually those who have achieved a high rank with their home company, and have subsequently been engaged to dance with other ballet companies around the world, normally performing the lead role. They are usually principal dancers or soloists with their home company, but given the title of Guest Artist when performing with another company.

Prima ballerina assoluta

The title or rank of prima ballerina assoluta was originally inspired by the Italian ballet masters of the early Romantic ballet and was bestowed on a ballerina who was considered to be exceptionally talented, above the standard of other leading ballerinas. The title is very rarely used today and recent uses have typically been symbolic, in recognition of a notable career and as a result, it is commonly viewed as an honour rather than an active rank.

References

- Jonas, Gerald (1998). Dancing: the Pleasure, Power, and Art of Movement. San Val. p. 130. ISBN 9780613637039.

- Miller, EH; Schneider, HJ; Bronson, JL; McLain, D (September 1975). "A new consideration in athletic injuries. The classical ballet dancer". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (111): 181–91. doi:10.1097/00003086-197509000-00026. PMID 125636.

- Turner, Bryan S.; Wainwright, Steven P. (24 March 2003). "Corps de Ballet: the case of the injured ballet dancer". Sociology of Health and Illness. 25 (4): 269–288. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.00347. PMID 14498922.

- Edwin Denby (1965). Dancers, Buildings, and People in the Streets

External links

Media related to Ballet dancers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ballet dancers at Wikimedia Commons