Barmah Forest virus

Barmah Forest virus (BFV) is an RNA virus in the genus Alphavirus. This disease was named after the Barmah Forest in the northern Victoria region of Australia where it was first isolated in 1974.[2][3] The first documented case in humans was in 1986.[4]

| Barmah Forest virus | |

|---|---|

| |

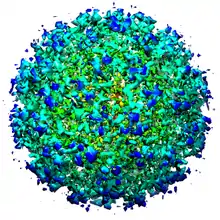

| Structure of Barmah Forest virus by cryo-electron microscopy. EMD-1886[1] | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Alsuviricetes |

| Order: | Martellivirales |

| Family: | Togaviridae |

| Genus: | Alphavirus |

| Species: | Barmah Forest virus |

As of 2015, it has been found only in Australia. Although there is no specific treatment for infection with the Barmah Forest virus, the disease is non-fatal and most infected people recover.[1][5] The virus was discovered in 1974 in mosquitoes in the Barmah Forest in northern Victoria.[6] The virus has gradually spread from the sub-tropical northern areas of Victoria to the coastal regions of New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia (WA). People are more likely to contract the disease in summer and autumn in Australia. In the south west of WA, however, spring has been found to have the highest incidence.[4]

Transmission

The virus can only be transmitted to humans by bites from infected mosquitoes. A number of mosquito species have been associated with vectoring the virus, including the Aedes vigilax and Culex annulirostris mosquito species.[7] Direct contact with an infected person or animal does not cause infection.[8] The virus is hosted mainly by marsupials, especially possums, kangaroos and wallabies.[5]

Symptoms

Symptoms include fever, malaise, rash, arthralgia, and muscle tenderness. Fever and malaise generally disappear within a few days to a week, but other symptoms such as joint pain may continue for six months or longer.[1][9]

The Barmah Forest virus causes similar symptoms as the Ross River virus, although they usually persist longer in persons infected with the latter.[5][8]

Most people may recover within a few weeks, but the minority can continue to have the symptoms for many months, and in the most severe cases, up to a year. A full recovery will be expected.[10]

Diagnosis

The Barmah Forest virus is diagnosed by examination of blood serum collected from potentially infected people.[4]

Documented cases

Barmah Forest virus (BFV) is the second most prevalent arbovirus in Australia.[7] It is causing an epidemic polyarthritis throughout the country.[11] No known deaths have been caused as a result of BFV and can affect all people regardless of age, gender or ethnicity.

During the years of 1995–2008 15592 BFV cases were recorded in Australia. Of these, Queensland recorded the highest number of cases being 8050, which was over 50% of all cases.[12] In 2011, 1855 people were diagnosed with BFV.[13]

In recent years, there has been an increasing trend of the number of BFV cases around Australia. This increase could be as a result of urban development and changes to land and irrigation practices which ultimately allow for increased mosquito breeding resulting in more BFV outbreaks.[14]

Prevention

The type of mosquito that transmits the virus can alter: the best way to ascertain an area is affected is by contact with local Health Officers. Precautions include:

- Removing water build-up to stop mosquitos from breeding.

- In the afternoon and early evening wear light coloured clothing which is loose fitted.[15]

- Regular use of insect repellent which can be used against mosquitos on exposed skin.

- 'Knock-down' insecticide before bed to clear out your house.

- Insect screening, including fireplaces, in hot weather.

Treatment

There is currently no specific treatment for the virus. The only treatment is trying to control and get rid of the symptoms that may occur. A doctor will advise and give treatment for the joint and muscle pain which involves resting and gentle exercise (to keep joints moving) . Medication may sometimes be necessary, but not always.[16]

References

- Kostyuchenko, V. A.; Jakana, J.; Liu, X.; Haddow, A. D.; Aung, M.; Weaver, S. C.; Chiu, W.; Lok, S. -M. (2011). "The Structure of Barmah Forest Virus as Revealed by Cryo-Electron Microscopy at a 6-Angstrom Resolution Has Detailed Transmembrane Protein Architecture and Interactions". Journal of Virology. 85 (18): 9327–9333. doi:10.1128/JVI.05015-11. PMC 3165765. PMID 21752915.

- Cashman, Patrick (2008-06-30). "Barmah Forest virus serology: implications for diagnosis and public health action". Communicable Diseases Intelligence. PMID 18767428. Retrieved 2015-04-07.

- Smith, D.W. (May 2011). "The viruses of Australia and the risk to tourists". Travel Medicine and Infectious Diseases. 9 (3): 113–125. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.05.005. PMID 21679887.

- Hueston, L.; Toi, C. S.; Jeoffreys, N.; Sorrell, T.; & Gilbert, G. (2013). "Diagnosis of Barmah Forest virus infection by a nested real-time SYBR green RT-PCR assay". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): E65197. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...865197H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065197. PMC 3720699. PMID 23935816.

- Barmah Forest Virus Archived August 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Queensland Health. Queensland Government. 11 May 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- Ross River virus and Barmah Forest virus—the facts. Department of Health, Victoria, Australia. 28 July 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- Naish, S.; Mengersen, K.; Hu, W.; & Tong, S. (2012). "Wetlands, climate zones and Barmah Forest virus disease in Queensland, Australia" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 106 (12): 749–755. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2012.08.003. PMID 23122869.

- Ross River Virus & Barmah Forest Virus in WA Archived 2012-03-21 at the Wayback Machine. Environmental Health Directorate. Department of Health, Western Australia 2006. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- NSW Government, (2013). "Barmah Forest virus".CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Barmah Forest virus infection - symptoms, treatment and prevention :: SA Health". www.sahealth.sa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2015-04-19. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- Ehlkes, Lutz (September 2012). "Surveillance should be strengthened to improve epidemiological understandings of mosquito-borne Barmah Forest virus infection". Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal. 3 (3): 63–8. doi:10.5365/WPSAR.2012.3.1.004. PMC 3730995. PMID 23908926.

- Naish, Suchithra; Hu, Wenbiao; Mengersen, Kerrie; Tong, Shilu (October 13, 2011). "Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Barmah Forest Virus Disease in Queensland, Australia". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25688. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625688N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025688. PMC 3192738. PMID 22022430.

- Naish, S.; Mengersen, K.; Hu, W.; & Tong, S. (2013). "Forecasting the future risk of Barmah Forest virus disease under climate change scenarios in Queensland, Australia". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): E62843. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862843N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062843. PMC 3655130. PMID 23690959.

- Naish, Suchithra (2011). "Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Barmah Forest Virus Disease in Queensland, Australia". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25688. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625688N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025688. PMC 3192738. PMID 22022430.

- "Ross River virus and Barmah Forest virus - the facts - Infectious Diseases Epidemiology & Surveillance - Department of Health and Human services, Victoria, Australia". ideas.health.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- "Barmah Forest Virus - Queensland Health". access.health.qld.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2015-03-23. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

External links

- "ICTVdB Virus Description—00.073.0.01.004. Barmah Forest virus". Archived from the original on 2010-04-29. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- Ross River and Barmah Forest viruses

- Queensland Public Health Services: Barmah Forest Virus

- Mozzies carrier of 'emerging virus'